World Refugee Survey 2008 - China

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - China, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50ca7b.html [accessed 8 June 2023] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

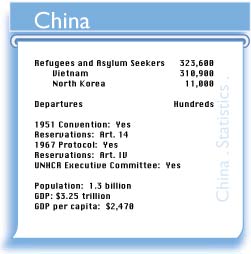

There was a continued decline in the number of North Korean refugees in China, with around 11,000 in the country at year's end. Because of increased enforcement along the North Korean border, fewer Koreans were able to cross to receive aid and return to North Korea than in previous years. As many as 80 percent of the refugees were women living with Chinese men, and there were additionally 5,000 to 8,000 children from these mixed marriages who had arguable claims to Chinese citizenship. In at least one case, China expressly recognized the Chinese citizenship of one and prevented the child's departure when its mother left the country for South Korea. In February, a group of about 20 North Korean border guards reportedly fled into China after their Government accused them of taking bribes to allow others to escape.

The deprivation that some fled was politically motivated, as North Korea withheld food and other goods from as much as a quarter of the population that it deemed hostile. North Korea also punished returned defectors with prison, forced labor, torture, and possibly execution had they met with non-Chinese foreigners or Christians outside the country. According to a March report from Human Rights Watch, punishments became more severe since late 2004, with prison sentences of one to five years for all defectors, including first-time offenders. As the North Korean Government's motives for such severe punishment appeared to be political, the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants considered North Koreans in China prima facie to be refugees. China, however, considered them illegal economic migrants.

China also hosted about 311,000 refugees from Vietnam, mostly ethnic Chinese, who fled Vietnam during and after the Sino-Vietnamese War in the early 1980s, mostly settling in the southern provinces of Guangxi, Guangdong, Yunnan, Hainan, Fujian, and Jiangxi.

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) also dealt with a small number of refugees from other countries, around 180 at the end of 2007, who lived in Beijing.

Refoulement/Physical Protection

Deportations of North Koreans dropped to the lowest levels in recent years, largely due to a lower refugee population. China deported fewer than 1,000 during the year, as compared to 1,800 in 2006. It maintained tight security in the immediate border region and around Olympic venues in Beijing, but did not launch other systematic efforts to locate and deport North Koreans. China also returned five Pakistani asylum seekers to Pakistan during the year, over UNHCR's protests. In April 2008, UNHCR reported that China had deported 15 refugees in pre-Olympics security sweeps of Beijing, including a 17-year-old Pakistani boy. It returned other refugees to Iraq, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan.

China allowed passage to South Korea via a third country only to those Korean refugees who gained public attention and the protection of a foreign embassy or consulate and only after five to six months of delay. China also denied UNHCR and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) access to its northeastern border with North Korea.

China was party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Although the Constitution allowed it to grant asylum to those who sought it "for political reasons," China did not have a procedure for doing so. China permitted a small number of asylum seekers of other nationalities to remain, mostly in Beijing, while UNHCR determined their status and sought to resettle them.

Hong Kong lacked a clear asylum policy and China did not consider that its obligations under the Convention and Protocol extended to it.

Detention/Access to Courts

China detained and deported North Koreans who came to its official attention, but did not launch systematic crackdowns as it had in the past.

China occasionally arrested asylum seekers for illegal stay or if they lost their passports, but generally released them if UNHCR found they were refugees. China's Public Security Bureau held all detained refugees and asylum seekers, and the detention enters were not subject to any independent monitoring. A detained Korean-American activist reported seeing Chinese guards beating North Korean detainees "to a pulp." Refugees and asylum seekers could not challenge their detention before any court.

North Korea's State Security Service reportedly attempted to infiltrate defector networks, in part by establishing a chain of Korean restaurants in China's Yanbian region, although China expelled some of the agents involved.

Some reports indicated that local governments near the North Korean border quietly issued identification cards to North Korean brides and the children of Chinese men. Others had to pay bribes of $100 to $400 to obtain registration on the Chinese household registry for their children.

Refugees under UNHCR's protection, along with North Koreans, had no official status under Chinese law, and could not use the courts to pursue their rights unless they held a visa or residence permit.

Vietnamese refugees enjoyed most of the rights of Chinese nationals. The provincial governments where they lived issued identification cards to all those over the age of 16, but not refugees or asylum seekers from other countries. Local authorities generally recognized the certificates that UNHCR issued to mandate refugees, but some officials objected to the letters it granted to asylum seekers and did not always accept them.

North Koreans had to use forged identification cards to move within the country. These ranged in price from $10 for easily spotted forgeries, to more sophisticated cards costing $1,260 or more that included Chinese household registration numbers.

Some Chinese citizens of Korean ethnicity bought North Korean identification cards from refugees for 1,000 to 1,500 yuan (about $140 to $210), hoping to use them to gain asylum in the West.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Vietnamese refugees had freedom of movement within the country but North Koreans did not. Police outside the Beijing area were not familiar with the certificates that UNHCR issued to refugees, and most did not travel outside the capital for fear of arrest by local police. Authorities also limited the movement of refugees without valid travel documents.

Some North Koreans used networks of safehouses and friendly groups to make their way through China to Mongolia, Russia, or southeast Asia. China built a barbed wire fence along the Tumen River, which marks the border with North Korea, and installed heat and motion sensors in the desert along its border with Mongolia. Thai officials reportedly indicated they would tip off the Chinese Government about the location of North Koreans preparing to cross from China into Thailand.

In September, China released Steve Kim, an American citizen of South Korean descent, after four years in prison. He had been charged with assisting North Koreans illegally cross the national border. In December, China released after only four months' detention another North Korean refugee who had obtained South Korean citizenship and who returned to guide others across the border.

As of March 2008, China denied exit visas to 17 North Korean refugees under UNHCR's protection in Beijing, reportedly demanding that UNHCR not grant asylum to any North Koreans until the end of the 2008 Olympics. Some of the North Koreans had been awaiting visas since July 2007.

China required some asylum seekers and refugees in Beijing, particularly those without proper identification, to stay in two designated hotels. Most lived in private residences with UNHCR assistance. In some cases, Chinese authorities objected if they attempted to change residences too often.

Some village leaders quietly and informally encouraged the presence and registration of North Korean women, because it helped ease a shortage of women caused by China's one-child policy and rural-to-urban migration. Authorities generally made more effort to crack down on North Koreans in urban centers than in rural areas.

A study conducted in 2004 found that 76 percent of North Koreans in China were living with Chinese citizens of Korean descent. At 5 percent each, missionaries' homes and mountain hideouts were the next most common places of residence.

China did not issue travel documents to refugees, and those whom UNHCR resettled to other countries relied on travel documents from their home countries or their new hosts.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

China allowed Vietnamese refugees to work freely. Other refugees needed a passport with a valid visa or residence permit to apply for a work permit. North Korean refugees, who generally left their country illegally, were not able to work.

The inability to work legally forced many North Korean women in China to depend on relationships with Chinese men to survive, which they formed either directly or through brokers or traffickers. Brokers typically sold North Korean women to Chinese men for between $700 and $1,000. Some entered knowing that traffickers would pair them with a Chinese husband but others did not. Some North Korean women found work as domestic servants and a few North Korean men found work as day laborers. The 2004 study found that only 22 percent of North Koreans in China were working. Of those who did work, only 13 percent reported receiving a fair wage, and 9 percent received none at all.

The 1996 Provisions on Administration of Employment of Foreigners in China prohibited citizens and businesses from employing foreigners, with no exception for refugees, but allowed special units from the Government to apply to the Ministry of Labor for work permits on behalf of foreigners. The fine for an employer sheltering illegal workers was $4,110. Permits were available only for special jobs for which no domestic workers were available and required certificates of qualification, labor contracts, and verifications of the demand in the labor market. Foreign workers also had to possess employment visas or a foreign resident certificate. Any foreigner wishing to change employers had to go through the process again. This law, however, did not apply in Hong Kong or Macao.

China's Constitution limited the rights to "own lawfully earned income, savings, houses and other lawful property" to citizens.

Public Relief and Education

The children of Chinese men and North Korean women could attend school through middle school and beyond if their family secured legal documentation. NGOs and missionaries provided some aid to North Koreans in the border areas.

China granted Vietnamese refugees public assistance and education on par with nationals but denied these services to refugees and asylum seekers of other nationalities. UNHCR provided assistance to refugees under its protection, including funding for housing, food, and medical assistance.

USCRI Reports

- USCR Condemns China's Execution of Uyghur Refugee Whom Nepal Had Forcibly Returned (Press Releases)

- USCR Lauds Senator Brownback's Call to End the Warehousing of Seven Million Refugees (Press Releases)

- East Asia: China Forcibly Returns North Korean Refugees to Death, Torture, and Imprisonment (Press Releases)

- USCR Condemns China and Nepal's Forcible Return of Tibetans, Calls China Among Top Violators of Refugee Rights (Press Releases)

- USCR Condemns China's Forced Return of North Korean Refugees (Press Releases)