In the Dark: Hidden Abuses Against Detained Youths in Rio de Janeiro

| Publisher | Human Rights Watch |

| Publication Date | 9 June 2005 |

| Citation / Document Symbol | B1702 |

| Cite as | Human Rights Watch, In the Dark: Hidden Abuses Against Detained Youths in Rio de Janeiro, 9 June 2005, B1702, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/42c3bcea0.html [accessed 18 May 2023] |

| Comments | When Human Rights Watch last visited Rio de Janeiro's five juvenile detention centers, in July and August 2003, we found a system that was decaying, filthy, and dangerously overcrowded. The facilities we saw did not meet basic standards of health or hygiene. Complaints of beatings and other ill-treatment were routinely ignored by the state's Department of Socio-Educational Action (Departamento Geral de Ações Sócio-Educativas, DEGASE), the authority responsible for the state's juvenile detention centers. The system lacked effective oversight; in particular, administrative sanctions against guards were rare, and none of the officials we spoke with knew of any case in which a guard had received a criminal conviction for abusive conduct. |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

I. Summary

At the end of the day, were the kids tortured or not? Why is it that every time we talk about a concrete case, we discuss everything, but nobody ever ends up knowing if it happened or not? Why is it that, in practice, the accuser always becomes the accused? Why can't a case ever be brought to a conclusion? Why do bureaucratic questions suddenly become paramount right then? Why do we need to go through an immense and unbearable set of procedures that leaves us with a profound sense of futility?1– Questions posed by Eliana Rocha, counselor, State Council for the Defense of the Child and Adolescent, to Sérgio Novo, director general, Department of Socio-Educational Action, at a council meeting on November 10, 2004.

When Human Rights Watch last visited Rio de Janeiro's five juvenile detention centers, in July and August 2003, we found a system that was decaying, filthy, and dangerously overcrowded. The facilities we saw did not meet basic standards of health or hygiene. Complaints of beatings and other ill-treatment were routinely ignored by the state's Department of Socio-Educational Action (Departamento Geral de Ações Sócio-Educativas, DEGASE), the authority responsible for the state's juvenile detention centers. The system lacked effective oversight; in particular, administrative sanctions against guards were rare, and none of the officials we spoke with knew of any case in which a guard had received a criminal conviction for abusive conduct.

DEGASE officials were quick to denounce our report, released in December 2004, claiming that it contained outdated information and reflected the practices of the prior administration. DEGASE director general Sérgio Novo described the report as "an injustice," telling the respected daily Folha de S. Paulo, "They show a reality that is completely different from what we have today."2

Despite DEGASE's protests to the contrary, we found on our return in May 2005 that little has changed in Rio de Janeiro's detention centers. As this report documents, beatings and other physical abuse continue. Living conditions in several detention centers have worsened. Critical shortages in staffing, food, and clothing in these detention centers mean that youths are exposed to the risk of cruel and degrading treatment on a daily basis.

The Educandário Santo Expedito is a case in point. Well over its official capacity when we first inspected it in July 2003, it was even more overcrowded when we returned in May 2005. On both occasions, youths were crowded into cellblocks in a single building. The living quarters in other buildings were destroyed in a November 2002 fire and were not repaired until late 2004. Although they have now been repaired, they are not currently used to house youths. The only notable improvement was the new coat of yellow paint on the barred doors leading into each cellblock, covering the peeling, dingy blue we saw on our first inspection. "Purely cosmetic," said Tiago J., a former guard, on hearing our description of what we had seen on our return visit to Santo Expedito.3

Beatings by guards are common in all detention centers with the exception of the Educandário Santos Dumont, the girls' detention facility. "It's bad [here] because they beat us," said seventeen-year-old Roberto G., referring to Santo Expedito. Asked who he meant and why they did this, he answered, "The guards.... Any reason. They hit us on the face, on the chest. They use their fists and also a piece of wood. It's the guards who do this." Some are worse than others, he told us. "This happens every once in a while. The last time was two weeks ago, on Thursday. A guard beat me."4

With the authorization of the State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth (Secretaria de Estado da Infância e da Juventude), we entered Santo Expedito and two other detention centers, the Educandário Santos Dumont and the Escola João Luiz Alves, before DEGASE officials refused to permit us to continue our investigation. Their action was both a remarkable act of insubordination – DEGASE is an agency of the state secretariat – and a telling indication that detention authorities were concerned that their practices would not pass muster.

Despite DEGASE's efforts to obstruct our investigation, we were able to review practices in the remaining centers, the Centro de Atendimento Intensivo-Belford Roxo (CAI-Baixada) and the Instituto Padre Severino, by examining court records and other documentary evidence and interviewing parents, released youths, detention officials, and others familiar with conditions in those centers.

The beatings and other ill-treatment that are routine in Rio de Janeiro's detention facilities are the product of a systemic failure of accountability. There is simply no effective independent monitoring of these institutions. Public prosecutors have the authority to inspect juvenile detention facilities but almost never do so. Public defenders have attempted to fill this role, but some twenty judicial districts lack public defenders, meaning that some youths in those districts go without any legal representation at all.

Judicial inspections focus on administrative details – the number of youths, the number of staff, the quantity of laundry detergent in each facility – but show little inclination to examine reports of abuse by guards. DEGASE's inspector general's office lacks the independence to carry out its mission.

In this report, Human Rights Watch's eighteenth on juvenile justice and conditions of detention for children around the world, we assess the treatment of children according to international law, as set forth in the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international human rights instruments.5

We use the word "child" in this report to refer to anyone under the age of eighteen. The Convention on the Rights of the Child defines as a child "every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier."6 This use differs from the definition of "child" in Brazil's juvenile justice law, which makes a distinction between persons under the age of twelve (who are considered "children") and those between twelve and seventeen years of age ("adolescents"). For this reason, and because Brazil's juvenile detention center may hold both adolescents and young adults between up to the age of twenty-one, this report uses the term "youth" to refer to any person between age twelve and twenty-one.7 We give aliases to all children and detained youths in this report to protect their privacy and safety..

II. Recommendations

Rio de Janeiro's Department of Socio-Educational Action (Departmento Geral de Ações Sócio-Educativas, DEGASE), now a branch of the State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth (Secretaria de Estado da Infância e da Juventude), has primary responsibility for the administration of the state's juvenile detention system. Human Rights Watch calls on DEGASE and, as appropriate, other state and federal entities, to implement the recommendations set forth in our December 2004 report as well as those of the National Council on the Rights of Children and Adolescents (Conselho Nacional dos Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente, CONANDA), the U.N. special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, the U.N. special rapporteur on torture, and the Committee on the Rights of the Child.

In particular, DEGASE should take the following steps in order to protect the human rights of youths in the state's juvenile detention system:

- Fill staffing shortages through the legally required "concurso público" (open competition) as a matter of priority.

- Provide current and new staff with regular professional training and other support.

- Prohibit the use of collective punishment.

- Establish a complaint system independent from guards and ensure that all complaints are investigated thoroughly, with appropriate discipline for staff who perpetrate violence and other abuses.

- Ensure that youths receive schooling, professional training, and other activities, including leisure activities, on a regular basis.

- Provide youths with items necessary for the maintenance of hygiene and personal cleanliness, as well as offering them frequent changes of clothing, individual mattresses and bedding, and adequate opportunities to bathe.

- Provide adequate, clean, and well-maintained facilities, particularly housing units, to the standard required for human dignity.

- Routinely notify the State Council for the Defense of the Child and Adolescent (Conselho Estadual de Defesa da Criança e do Adolescente), the State Secretariat of Childhood and Youth, the state prosecutor's office, the state public defender's office and the juvenile court of reports of abuse, escape attempts, riots, rebellions, and other serious disturbances or security breaches.

The State Prosecutor's Office should regularly inspect juvenile detention centers without notice, taking appropriate action against detention center directors who fail to remedy deficiencies. Specifically, it should:

- Conduct regular and systematic surprise inspections of juvenile detention centers.

- Bring administrative and judicial proceedings required to correct any illegalities and irregularities in juvenile detention centers, as authorized by the Statute of the Child and Adolescent.

- Investigate, prosecute, and punish those responsible for abuses in juvenile detention centers.

The State Council for the Defense of the Child and Adolescent (Conselho Estadual de Defesa da Criança e do Adolescente), a body that includes civil society as well as governmental representatives, should exercise its mandate to conduct regular and systematic surprise inspections of juvenile detention centers and should send reports of such inspections to the appropriate governmental bodies so that they may initiate the administrative and judicial proceedings required to correct any illegalities and irregularities it finds.

The State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth should finish and submit its proposal to make the DEGASE Inspector General's Office autonomous from DEGASE itself and reporting directly to the secretariat. The new office should have full access to juvenile detention centers and all other investigatory and enforcement powers necessary to carry out its mandate.

The State Public Defender's Office (Defensoria Pública do Estado do Rio de Janeiro) should fill staffing shortages through the legally required "concurso público" (open competition) so as to provide legal counsel to adolescents in every judicial district in the state of Rio de Janeiro and at every step of the judicial process following apprehension.

Gov. Rosângela Rosinha Garotinho Barros Assed Matheus de Oliveira should issue a decree to make the DEGASE Inspector General's Office an autonomous entity that reports directly to the State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth, with full access to juvenile detention centers and all other investigatory and enforcement powers necessary to carry out its mandate.

CONANDA should include in its draft bill on socio-educational measures an explicit mandate for independent monitoring of the juvenile detention system by members of civil society.

For its part, the Brazilian Congress should condition the receipt of federal funding for juvenile justice programs on state guarantees of independent monitoring of juvenile detention centers.

III. Juvenile Detention in Rio de Janeiro

When Human Rights Watch last visited Rio de Janeiro's five juvenile detention centers, in July and August 2003, we found a system that was decaying, filthy, and dangerously overcrowded. Almost without exception, the facilities we saw did not meet basic standards of health or hygiene. Complaints of ill-treatment were routinely ignored by the state's Department of Socio-Educational Action (Departamento Geral de Ações Sócio-Educativas, DEGASE), the authority responsible for the state's juvenile detention centers. The system lacked effective oversight; in particular, administrative sanctions against guards were rare, and none of the officials we spoke with knew of any case in which a guard had received a criminal sentence for abusive conduct.8

Returning in May 2005, despite DEGASE's protests to the contrary, we found that little has changed. As this report documents, conditions in several detention centers have worsened, with critical shortages in staffing, food, and clothing, continued physical abuse, and appalling squalor.

Brazil's national juvenile justice law, the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent, celebrates its fifteenth anniversary in July 2005. The statute is a model law on paper and in some respects exceeds the guarantees contained in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international treaty governing children's rights to which Brazil is a party.

In Rio de Janeiro, the state juvenile justice system serves approximately 2,000 youths, some 900 of whom are awaiting trial or serving periods of detention.9 For those youths, the statute remains a hollow promise.

Youth and Crime

Contrary to popular perception, few violent offenses are committed by youths under the age of eighteen in Brazil. In 2001, for example, youths under age eighteen were identified as responsible for approximately 2.2 percent of homicides and 1.6 percent of robberies by threat or force (roubo), according to data from the state public security secretariat.10

More recent data from the state public security secretariat and the juvenile court show similarly low rates for violent offenses committed by juveniles. Youths under eighteen were known to be responsible for less than 1 percent of homicides in each of 2003 and 2004 and between 1.5 and 3.6 percent of robberies by threat or force in 2003.11 Direct comparisons of these data are difficult – juvenile court records show the number of youths that have been found guilty of particular acts, while the public security secretariat data are based on crime reports. In addition, the categories used in each set of data may differ slightly. Nevertheless, these more recent data broadly support the conclusion that the overwhelming majority of violent crime is perpetrated by adults rather than by youths under the age of eighteen.

Contrary to another common misperception, those serving sentences in juvenile detention facilities are not exclusively held for murder, robbery, and other violent offenses, as the chart below shows. Many are held for nonviolent drug offenses; others are detained for violating conditions of a sentence.12 One girl in Santos Dumont was held for desacato (the offense of insulting a public official) and resisting arrest.13

|

Youths Detained for Non-Violent Offenses in Rio de Janeiro | |||||

| Center |

Theft |

Failure to obey prior judicial order |

Nonviolent drug offenses |

Gun possession |

Insulting public official & resisting arrest |

| CAI-Baixada* |

7 |

-- |

53 |

-- |

0 |

| João Luiz Alves |

4 |

8 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

| Santo Expedito |

3 |

27 |

22 |

1 |

0 |

| Santos Dumont |

4 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

1 |

| Total |

18 |

35 |

93 |

1 |

1 |

| *At the time we obtained these data for CAI-Baixada, the center had ten recently arrivals whose offenses were unknown.

SOURCE: DEGASE, "Planilha de adolescentes internos – Centro de Atendimento Intensivo – Belford Roxo," May 31, 2005; DEGASE, "Planilha de adolescentes internos – Escola João Luiz Alves," April 30, 2005; DEGASE, "Planilha de adolescentes internos – Educandário Santo Expedito," May 31, 2005; DEGASE, "Planilha de adolescentes internos – Educandário Santos Dumont," April 30, 2005. | |||||

These data suggest that detention in Rio de Janeiro is not always used as a measure of last resort, as required by international law and Brazil's Statute of the Child. Under the statute, in fact, youths may only be detained for offenses involving violence or serious threats of violence, repeat serious offenses, or for the "repeated and unjustified failure" to comply with conditions of a sentence.14

IV. The Current Crisis

Today there are some six guards and about 207 adolescents. The adequate number would be around thirty guards. Right now the situation is impossible.15– Guard at Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

Tomorrow there is no breakfast, no lunch. And if a rebellion blows up, who's responsible for it? I am worried. We already sent a letter to DEGASE explaining this, but nothing gets resolved over there.16– Staff member at Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

The majority of Rio's juvenile detention centers are under constant threat of violent rebellion. This danger has grown in 2005, as state authorities failed to act quickly and decisively to resolve shortages in staffing, food, clothing, and other supplies and interruptions in schooling and other activities that have worsened since the start of the year. Even before the current crisis, however, excessive use of cell confinement, inadequate staffing, lack of access to schooling, and idleness were routine features of Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers.

The number of guards and other staff in Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers is dangerously low. Some centers commonly operate with one guard on duty for every thirty to forty youths. In Santo Expedito on at least one occasion, a total of two guards worked the day shift at a time when the center held over 200 youths.

Staff shortages have adverse effects on institutional security, on employee morale, and on detention centers' respect for youths' rights. Not all guards commit abusive acts. But when they are forced to cope with a lack of personnel, even well-intentioned detention officials are tempted to cut corners – meting out discipline with blows and kicks, cutting off schooling and recreational activities, and confining youths to their cells for unreasonable periods of time.

Such shortages are not new. When Human Rights Watch inspected Rio de Janeiro's detention centers in July and August 2003, for example, Padre Severino had on average one guard for every thirty youths, an official there told us.17 CAI-Baixada had ten staff members, a number that included the driver and the porter, assigned to each shift to cover a population of 187 youths.18

Judge Guaraci de Campos Vianna, Rio's chief juvenile court judge, told us in May 2005 that the juvenile detention system as a whole has always been understaffed. A recent study by the judiciary found a deficiency of around 800 employees throughout the juvenile justice system, a number that includes those who administer community service, probation, and other less-restrictive "socioeducational measures" as well as those who work in detention centers, Dr. Vianna told us.19 Human Rights Watch was not able to find out the total number of employees in the juvenile justice system, but Anderson Sanchez, spokesperson for the Penitentiary and Socio-Educational System Employees' Union (Sindicato dos Servidores do Sistema Penitenciario e Sócio-Educativo), told us that DEGASE currently employs approximately 650 guards. When we asked if it was likely that the deficiency of 800 was close to the total number of current employees, Sanchez replied, "That sounds about right," saying that double the current number of employees was needed.20

A judicial order at the end of December 2004 resulted in the summary dismissal of some 300 guards and other employees due to contractual irregularities, exacerbating the longstanding staff shortages. State officials have been vague about the timetable for filling these positions. In comments reported on March 14 in the Rio de Janeiro newspaper EXTRA, DEGASE director Sérgio Novo said that the department was in the process of hiring new personnel, but he said only that these positions would be filled sometime in 2005.21

The mass dismissal had a predictable effect. On February 17, 2005, the director of Santo Expedito reported:

[T]he number of guards working each shift has proved to be insufficient in view of the far superior number of detained adolescents (163 detainees).... The adolescents have observed the disproportionate number of detainees to staff, a fact that also places the security of this center at risk.22

The ratio of youths to guards is now more than thirty to one at some centers. On the day we visited Santo Expedito in May 2005, for example, there were six guards on duty for 207 youths, a youth-to-guard ratio of 34.5 to one. On at least one day earlier in the month, the center had only two guards on its day shift, Simone de Souza of the public defender's office told us.23 When we asked a guard at Santo Expedito what a safe staffing level would be, he told us that at least thirty guards, one for every seven youths, should be on duty every shift.24

Santo Expedito is not the only detention center with staffing shortages. In response to an inquiry from the public defender's office, the director of CAI-Baixada reported in January 2005 that his center had fifty-five guards. Twenty-five more were needed, he said.25 The director of Santos Dumont reported that her detention center required twelve additional guards to be adequately staffed.26

Even before the mass dismissal, guards received insufficient training and support, as we noted in our December 2004 report.27 A representative of the the Union for Employees of the State Secretariat of Justice of Rio de Janeiro told Human Rights Watch that new guards receive only a week of training before working.28 "When a guard tries to increase his level of education, he runs into a lot of difficulties. They [DEGASE officials] discourage this," said Maria Helena Zamora, a professor with the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro who specializes in juvenile detention issues. "Guards don't receive assistance; on the contrary, their lives become more difficult."29 With the substantial reduction in staffing levels, guards now face additional pressures and are more unlikely to receive professional training and development.

Current staffing levels also increase the risks that come with routine transfers of youths from their cellblocks to classes, outdoor activities, and meals. On the day that Santo Expedito had only two guards on duty, for instance, groups of up to ninety youths moved between the cellblocks and other parts of the detention center, Dr. Souza said.30

In addition, staffing shortages mean that guards cannot be spared to transport youths to court. Youths in Padre Severino have on occasion missed their hearings for this reason, the public defender's office told us.31 Such shortages lead to violations of youths' right to a trial without delay. They also contribute to overcrowding in Padre Severino because most youths remain at that center only until their case is resolved.

Detention centers also lack a sufficient number of social workers, psychologists, and other professional staff responsible for preparing the six-month reports that guide judges in their decisions to modify sentences or order youths' release. These staff members can also provide critical support to detained youths. Perhaps with these reasons in mind, CAI-Baixada's director wrote in January 2005 that the center's "real need" was a threefold increase in professional staff "so that the adolescent does not solely become a piece of paper."32 CAI-Baixada had four social workers and one psychologist for some 160 youths in late January 2005, a ratio of one to forty and one to 160 respectively.33

Idleness and Cell Confinement

In response to staffing shortages, detention center authorities in Padre Severino and Santo Expedito suspended classes and sharply reduced other activities for youths in January 2005, meaning that they spend much of their time locked in their cells with nothing to do. Classes at Santo Expedito did not resume until mid-May. Enforced idleness was a longstanding problem in Padre Severino and other detention centers long before the current crisis, but the protracted lockdowns increased the risk of the centers erupting in violence.

Interruptions in Schooling, Vocational Training, and Other Activities

Authorities in Santo Expedito and Padre Severino suspended classes, recreation, and nearly all other activities at the beginning of January 2005, citing security concerns related to understaffing.34 Classes were due to resume in Santo Expedito on February 21, 2005, but the center director wrote to the public defender's office on that day to explain:

[W]e inform you that it was not possible to send Santo Expedito detainees to school on February 21, 2005, the date scheduled by the Secretariat of Education for the beginning of the school year, bearing in mind the current deficiencies in the number of guards [agentes de disciplina] . . . .35

School remained closed at Santo Expedito until at least May 14, 2005.36 Two vocational training courses, a pizza-making course and a microcomputer maintenance course, were also suspended at the center because "the teachers felt insecure due to the reduced numbers of employees."37 Interviewed in late May 2005, seventeen-year-old Anderson F. told us the only activities other than classes that were available at Santo Expedito were soccer, a bottle recycling program, and church services.38

In Padre Severino, near-complete idleness has been the rule for much of 2004 and 2005. André S., who left Padre Severino in May 2004 at age seventeen, told us that there were no activities there besides sports. "At Padre, we would wake up, then we had breakfast, then we would stay waiting for lunch," André S. recalled. "We created a game with rocks. We stayed watching the time pass. [It was] like this until we slept. There was nothing to do."39 Marcos G. told us there were no activities at all in Padre Severino when he was there in December 2004, adding, "All we did was use the [athletic] court once in a while."40

In late January 2005, the director of Padre Severino wrote to the public defender's office, "Currently we are not running any activity with the adolescents," attributing the lack of activities to the school holiday and insecurity caused by understaffing.41 Schooling has since resumed at Padre Severino; other than classes, however, the only activity is occasional outdoor recreation. Márcia Castro, a lawyer with the Bento Rubião Foundation Center for the Defense of Human Rights (Centro de Defesa dos Direitos Humanos Fundação Bento Rubião), told Human Rights Watch in May 2005, "At least now they play soccer once in a while. Before, even that did not really happen."42

Similarly, detention officials in CAI-Baixada sharply cut back activities in January 2005. As a result, the center's director wrote, "Our concern at the moment lies in the idleness the adolescents find themselves in, which can result in negative reactions followed by internal conflicts and attitudes counter to order and discipline."43

Lengthy Periods of Lockdown

The suspension of schooling, vocational training, and other activities in Santo Expedito and Padre Severino meant that youths in those centers spent most of the first five months of 2005 locked in their cells with little or nothing to do. In February 2005, Simone de Souza of the public defender's office advised the State Council for the Defense of the Child and the Adolescent (Conselho Estadual de Defesa da Criança e do Adolescente) that youths in the two centers had been on lockdown, let out of their cells only for short periods each day, since the beginning of January.44

Although schooling has resumed, we heard from youths that they continue to spend much of their time locked in their cells. Asked how he spent a typical day in Santo Expedito, seventeen-year-old Marcos G. responded "In the wing really, inside the cell. Only leave for breakfast, school, lunch, dinner, and once in a while soccer." Padre Severino was even worse, he said. "There we would stay locked up the whole time.... There was nothing to do."45

Shortages of Food and Clothing

At the same time that the mass dismissal has placed strains on staffing levels, food and clothing have been in short supply at several detention centers. In Santo Expedito, the quantity of food available "has proved to be insufficient for the necessary daily consumption of adolescents and staff members," the center's director informed judicial authorities on February 16, 2005.46 These food shortages had not been resolved by May 23, when a staff member complained to public defenders in the presence of Human Rights Watch representatives that there was no food for breakfast or lunch the following day. The DEGASE general administration knew of the problem but had done nothing, the staff member said.47

Food shortages are a problem in CAI-Baixada as well, according to a lawsuit filed by the public defender's office.48 We heard accounts that suggested the same was true in Padre Severino. João T., a seventeen-year-old who was held in Padre Severino until May 2005, reported that the food had the taste of baking soda, an additive often used to induce a feeling of satiation with smaller amounts of food.49 Hearing such accounts, Marcia Castro, a lawyer with the Bento Rubião Foundation, "That at least indicates that there isn't enough food there."50

A member of the State Council for the Defense of the Child and the Adolescent raised the food shortage in Santo Expedito with a representative of Rio de Janeiro's Secretariat for Childhood and Youth at an extraordinary meeting of the council on February 23, 2005. In response, the Secretariat reported back to the public defender's office the following week that secretariat records reflected normal food purchases for the period, a fact that suggests that the shortages were the result of internal distribution problems.51

Clothing is also in short supply at nearly every detention center. In February 2005, the director of Santo Expedito wrote of the "need to obtain clothing materials for the detainees in quantities sufficient enough so that basic bodily hygiene is not compromised (aiming at frequent changing of clothing)."52 Our interviews with youths indicate that clothing is not changed regularly at Santo Expedito and Padre Severino, as discussed below in the "Conditions of Detention" section.

The Riot That Never Happened

Youths in Santo Expedito rioted on March 28, 2005, after the center had operated for nearly three months with shortages of food and clothing, an extended suspension of schooling and other activities, and a sharp reduction in staffing levels. The riot broke out after a failed escape attempt. The police report obtained by Human Rights Watch notes at 2:15 in the morning a guard "heard some noises and saw that some minors were breaking a wall in the interior of the housing unit with the intention of escaping."53 Upon raising the alarm, the guard "entered into negotiations with the minors to try to end the riot."54

The director of Santo Expedito arrived after guards began talks with youths. After "unsuccesful negotiation with the minors," he ordered guards to enter the housing unit.55 The guards then "entered and succeeded in stopping the illicit act of the minors."56 Seventeen youths, all of those in the police report list of persons involved in the escape attempt, were admitted to the Medico-Legal Institute (Instituto Médico Legal) hospital with injuries following the event. No guard was reported as injured in the police record.57

When a reporter called Santo Expedito to inquire about the riot, center staff denied that one had occurred.58 The reporter eventually found a staff member who agreed to speak to her on condition of anonymity. The staff member acknowledged that a riot had taken place and attributed it to the poor conditions in the center.59

We asked Judge Vianna, the chief judge for the branch of the juvenile court with jurisdiction over juvenile detention, about the riot when we interviewed him in May 2005. "There was no riot," Judge Vianna replied. "There was an escape attempt. Where did you get this word 'riot'?" When we told him that the event was described as a riot in the police report, he responded, "Nobody sent me anything."60

Judge Vianna's reaction is typical of the official response to this incident. In the course of researching this report, we learned of other disturbances that were not reported publicly and, if Judge Vianna's comments to us are any indication, have apparently never been investigated. For example, we heard from a guard at Santo Expedito that youths rioted in late December 2004, during the week after Christmas. The youths "broke everything" in their housing unit, a unit that has since been deactivated, the guard told us.61 The particular youths involved belonged to the Terceiro Comando, one of Rio de Janeiro's minority drug factions, who were housed in a separate wing apart from the majority Comando Vermelho youths for security reasons. Since the de-activation of the Terceiro Comando housing block, the two groups now dangerously inhabit the same wing, albeit in separate housing units.62

V. Beatings and Collective Punishment

"They beat us. They beat us with wood," Carlos P., a sixteen-year-old in Santo Expedito, said in a rush as soon as he sat down to speak with us. When Human Rights Watch's researcher asked him who did the beating, he replied, "The guards [os agentes]."63

We heard similar accounts from other youths we interviewed about their experiences in Santo Expedito and Padre Severino. When we asked Marcos G., age seventeen, whether he felt safe in Santo Expedito, he said, "Not at all. They beat us all the time. In Padre also. You get a thrashing on arrival."64

Anderson F., age seventeen, told us that he had been beaten in Padre Severino nine days before we spoke to him in May 2005. "One of those officials bashed me there. You've seen this purple eye," he said, pointing to a bruise below his right eye. He continued:

This is from there.... We were playing a game, and they thought we were fucking with them. It was time for lights out and they were having a barbecue outside.... At that time, there can't be any more noise. So then they caught me, because I was part of the group, and they gave me a bunch of blows to the face.65

Silvia R., the mother of seventeen-year-old Marcos R., saw a guard hit another youth when she was visiting her son in Padre Severino in May 2005. "I saw an adolescent take two blows during the time for visits, in front of everybody, including his mother," she said. She explained:

The adolescents were mouthing off. So a [female] guard gave two blows, hard blows with her open hand, on the back of one. She looked at the other and said, "We'll talk later." Right away I got up to complain, but my son asked me, "Mom, don't do this, because I'll get beaten also."

We asked her if she ever saw another situation like this one during a visit. "Yes," she replied. "Once in a while I saw an adolescent taken away by a guard. When he returned, he would have a bruise on his head, and he said he fell. No way did he fall."66

Other parents reported that the guards in Padre Severino beat their sons. For example, Cristiane B.'s son told her that guards had beaten him. "He had these purple bruises. But it wasn't possible during the visit to lift up his clothes to see. If he had, they would have beaten him even more inside."67

We heard reports of beatings at CAI-Baixada as well. "In CAI I was beaten also, but less than in Padre," André S. told us. "I only took one blow on the back there."68 The girls we interviewed in Santos Dumont, in contrast, told us that they had not seen or heard of beatings in that detention center.69

Forceful blows with an open hand were the most common method, youths told us. "Many slaps on the face," reported João T., age seventeen. "I've seen kicks also, them kicking others. Slaps on the chest, too."70 Guards in Padre Severino and Santo Expedito also beat youths with pieces of wood, some of which they gave names. André S. told us:

In Padre, there was the famous Kelly Key. A big piece of wood, tough to break. Whenever they took it out, everybody got quiet. They also had the Thundercat, a big, thick club, enormous. The Thundercat sword.... They beat us with that, too. They gave us [open-handed] blows on the chest and the face. They hit us right on the face.71

"I ended up swollen here," he added, pointing to his arm. He was hit twice on the head on another occasion, he said.72 His account was not the first time we had heard of the use of "Kelly Key" – in November 2004, the nongovernmental organization Projeto Legal reported that a guards in Padre Severino had delivered blows to a youth using "a piece of wood called 'Kelly Key.'"73

When guards in Padre Severino and Santo Expedito beat youths, it was often for failing to follow arbitrary rules. In Padre Severino, for example, André S. told us:

You had to eat fast. One person couldn't finish before [the others]; otherwise, those who didn't finish were beaten. And no talking. Keep your head down and stay quiet. If you speak, it's over. I saw one guard bash a boy's chin into the table.74

Other instances of violence lacked even the pretense of a justification. For example, Silvia R. told us that a guard threw toiletries at her son. She explained how this happened:

They're numbered, you know? So my son was new there; he didn't know the system, so he didn't know that normally they shout out their numbers and throw the supplies into the cells. So my son went to the door of the cell thinking that he would be handed [the soap]. The guard threw the soap in my son's face. During the visit, I saw that he had a bump on his eyebrow.75

We also heard reports that guards beat youths after provoking them with insults. In Padre Severino, for example, "they have that tendency," André S. reported. "They know that our mothers are sacred [to us]. They keep insulting our mothers. So then one of us will say something and then they'll give him a blow to the face."76

Guards administered some beatings as collective punishment. For instance, seventeen-year-old João T. told us that when he was in Padre Severino, "There when they come to beat [somebody] in one cell, they beat [people] in all [the cells], not just those who did something, and that's wrong. In a cell, if somebody misbehaves [fazer bagunça], everybody pays."77 André S. said, "In Padre, if one person does something, everybody pays. I got beaten because of [something done by] somebody else. If one person got up to something, everybody paid for it."78 Anderson F. gave a similar account. "In Padre, one person does something, but everybody pays. It isn't that somebody takes the blame and just that person gets beaten."79

Marcos G. described a recent instance of collective punishment in Santo Expedito:

One day just a while ago they locked us all down here. They beat everybody, everybody from the section. They stopped only when some people took the blame.... But I didn't have anything at all to do with it. All the same, we stayed locked up all day in a room without water, without food, without anything. There were about fourteen of us. We stayed there for one day. They gave us something to eat for lunch and dinner only after a long time. At the beginning there wasn't any way to go to the bathroom, and finally after a long time they took us out to go.... . The ones who took the blame were taken before the court .... They went through the system all over again.80

André S. initially told us that guards did not administer collective punishments at CAI-Baixada. "There, only those who did something paid for it," he said. Later in our interview, however, he suggested that group punishment did occur there. Explaining how a beating might occur, he said:

For example, if there were a bunch of people talking at 10 pm, then they would take only the one who was talking out of the cell to the little room. They had a little room where they beat people between the offices and the infirmary and the triage area where the most rebellious stayed. If nobody admitted to it, they would take out everybody and give us blows on the chest.81

We heard accounts that extended cell confinement is used as a group punishment as well. Maria N., a sixteen-year-old in Santos Dumont, told us that when one person does something wrong, "All of us get locked up for two days at most or maybe three."82 Youths reported the same at Santo Expedito.

It goes without saying that Brazilian and international law prohibit guards from beating youths in detention.83 International standards also call for the prohibition of collective sanctions.84 More generally, international standards only permit authorities to use force in restricted circumstances – for example, to prevent a youth from inflicting self-injury, injuries to others, or serious destruction of property. Even then, the use of force should be limited to exceptional cases, where all other methods have been exhausted; use of force should never cause humiliation or degradation. Finally, detention center officials should always inform family members of injuries that result from the use of force, and should do so immediately if the use of force results in serious injuries or death. 85

Much of Santo Expedito was destroyed in a November 2002 fire, leading to severe overcrowding in the remainder of the facility when Human Rights Watch visited in July 2003.

© 2003 Michael Bochenek/Human Rights Watch.

When Human Rights Watch returned to Santo Expedito in May 2005, the destroyed portions of the buildings had been renovated but were no longer used for housing areas. A bottle recycling project and administrative offices occupy an area that formerly contained approximately 45 percent of the detention center's cells.

© 2005 Michael Bochenek/Human Rights Watch.

VI. Conditions of Detention

They've committed crimes, okay. There should be help in the first instance, not throwing them in prison, not keeping them without being able to call their family. Somebody won't straighten out in Padre Severino. The problem of marijuana, he [my son] picked up this habit inside. My son returned full of rage, of aggression, without any help.86– Neusa M., whose son was in detention in 2004, interviewed in Rio de Janeiro, May 12, 2005.

In December 2004, when Human Rights Watch released its last report on juvenile detention in Rio de Janeiro, DEGASE director general Sérgio Novo told the press that he was "indignant" at our findings, which he described as "an injustice." "They show a reality that is completely different from what we have today," he declared to the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper.87 In fact, Human Rights Watch's six-month review of Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers found that little has changed. If anything, detention conditions have worsened in several important respects.

The Educandário Santo Expedito is a case in point. It held 181 youths the week we visited in July 2003, 9 percent over its official capacity of 166. When we returned in May 2005, it held 207 youths, 24 percent more than it was designed for. On both occasions, we found that its true capacity was closer to 90 – entire cellblocks destroyed in a November 2002 fire were not repaired until late 2004, and they are not currently used to house youths. The only notable improvements were the fresh coats of paint on the doors leading into each cellblock, which are now yellow instead of a peeling, dingy blue, and on the basketball court.

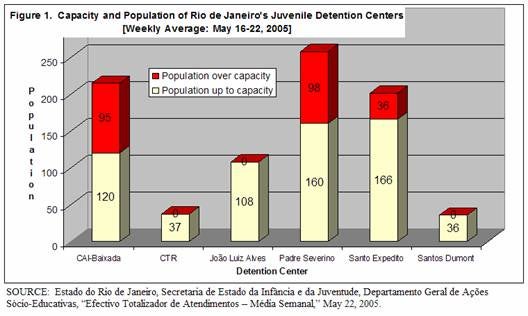

Overcrowding is the rule at most other detention centers as well. CAI-Baixada is at 179 percent of its capacity. Padre Severino is at 175 percent of capacity. Santos Dumont was not filled to capacity when we visited, but officials there told us that it periodically reaches 150 percent. Only João Luiz Alves, the closest thing Rio de Janeiro has to an adequate detention center, consistently holds fewer youths than it is designed for.

Squalor continues to be the order of the day. Cells are filthy, dark, and infested with vermin. At times, youths wear a single change of clothing for a week at a time. Youths do not always have access to soap and toothpaste, particularly in Padre Severino. Shortages of mattresses and bedding are common, and extreme levels of overcrowding mean that youths must often share beds. Unsurprisingly, scabies and other contagious diseases thrive in such conditions.

All of Rio de Janeiro's detention centers are dilapidated and badly in need of repair, but we heard particular complaints about Santos Dumont, the girl's detention center. When we visited the center, a guard commented, "What's bad here are the rooms. Look. Everything is wet, moldy. Really they have to renovate everything here."88 André Hespanhol, a lawyer with the nongovernmental organization Projeto Legal, agreed with the guard's assessment, saying of the rooms, "They're horrible. And it would take just a little bit to improve them. About 20,000 reais [U.S.$8,300] would be sufficient to redo everything there."89

The quality and amount of food was a problem in most centers, with the strongest complaints coming from those in Santo Expedito. "Here the food is very bad. Spoiled meat." Marcos G. had recently found white bugs in his food, he told us.90

Youths in every facility we visited told us that they were now attending classes, but that was not the case for much of 2005. As described in the previous section, classes were suspended starting in January in CAI-Baixada, Padre Severino, and Santo Expedito due to an acute shortage of guards and other personnel. Schooling resumed in Santo Expedito only one week before our visit, according to the public defender's office.91

The staffing shortage has also meant a sharp reduction in recreation and other activities, meaning that youths now spend much of their time locked in their cells. Marcos G. reported that when he was held in Padre Severino, "We only used the field once in a while.... There we stayed locked up the whole time. The place was stinking like hell. There was nothing to do."92 The same is true in CAI-Baixada, according to a suit brought by the public defender's office in March 2005 over conditions in that center.93

Juvenile detention is intended to serve a rehabilitative purpose. In Rio de Janeiro, it fails not only to achieve that end but also to provide basic conditions of dignity and humanity. "These boys deserve punishment because they made mistakes," said Silvia R., the mother of a seventeen-year-old held in Padre Severino until May 2005. "But they shouldn't be treated like animals."94

Overcrowding

Overcrowding is particularly serious in CAI-Baixada, Padre Severino, and Santo Expedito, as the chart below show. CAI-Baixada and Padre Severino each held in excess of 175 percent of their rated capacity during the week of May 16, 2005, DEGASE reported. Santo Expedito was at 124 percent of its official capacity that week.95

The situation is even more serious in Santo Expedito than it appears from these data. Its official capacity of 166 does not reflect the fact that many of its cellblocks have been converted to other uses. In our December 2004 report, we noted that several buildings had been largely destroyed in a November 2002 fire; these buildings had not been repaired when we visited in July 2003. When we returned to the center in May 2005, we expected to find that these areas had been renovated, easing the pressure on the other cellblocks. We found that the buildings had been repaired but are now used as a recycling center, meaning that all youths continue to be crowded into cellblocks in a single building. Based on our discussions with detention center staff and our inspection of the facility, we estimate the true capacity of Santo Expedito to be 90 rather than 166. With 207 youths in detention on the day of our visit, it held 230 percent of its estimated true capacity.

Overcrowding in Santo Expedito is such that youths must often share beds or sleep on the floor. Anderson F., a seventeen-year-old in Santo Expedito, explained, "Some stay on the ground, others on top [on the bed]. There one sleeps with his head one way and the other with his head the other way" so that they can fit on the bed.96

Santos Dumont held thirty-three girls when we visited in May 2005, seven under its official capacity of forty. Nevertheless, it is periodically overcrowded. One guard told us, "Now it's okay because we have, what, twenty here, so we have a bed for everybody. It's tough when there are fifty or sixty. Then we have to put two in a bed or even some on the floor."97

Living Conditions

Rio de Janeiro's detention centers fail to meet basic standards of health and hygiene. Detention centers report shortages of soap and toiletries; in some, youths wear a single change of clothing for up to a week before it is washed.

The youths we interviewed were particularly critical of the unhygienic conditions in Padre Severino. "The cells were all filthy" in Padre Severino, said André S., detained in Padre Severino in early 2004, when he was seventeen.98 Asked if the showers were clean in Padre Severino, seventeen-year-old Marcos G. responded, "No way. It was filth. It stunk like hell."99 Reports of rats in Padre Severino were common among youths and parents we interviewed. "There were rats and centipedes," André S. told us.100 "There were rats," Marcos G. reported. "At night we would see lots of them running around."101

The public defender's office described CAI-Baixada in similar terms in a lawsuit filed in March 2005:

The infrastructure is precarious. The dormitories are dirty, fetid, and unhealthy, with leaks that have produced mold on the walls, making the place prone to respiratory illnesses and the dissemination of other infections, aggravated by the fact that the adolescents do not receive enough clothes to change them daily, as well as not having adequate facilities for their physiological needs and for daily bathing.102

In addition, youths in Padre Severino and other facilities often do not have bedding and mattresses; when they do, they are often old and worn. João T., seventeen, compared conditions at Padre Severino with those at João Luiz Alves. "There [in Padre Severino] . . . the mattresses were old. The foam was all worn down. Not like here [in João Luiz Alves]. Here they're good. There you ended up with your back hurting."103 André S. told us that he didn't have a mattress during the forty-five days he spent in Padre Severino in early 2004.104 The public defender's office has complained of a shortage of mattresses and bedding in CAI-Baixada, João Luiz Alves, and Santos Dumont as well.105

Those detained in Padre Severino told us that they did not regularly receive items such as toothpaste and soap. Marcos G. depended on his mother to bring him soap and toothpaste when he was in Padre Severino. "My mother brought it, but once they told her that toothpaste couldn't come in," he recounted.106 André S. told us that getting toothpaste there "was difficult. We got it every once in a while, like that, on our fingers."107 Silvia R. brought her son soap when he was in Padre Severino, but she said that the guards also issued soap to the youths periodically.108

The situation in CAI-Baixada is similar, according to a suit filed by the public defender's office in March 2005. Among other shortcomings, the suit charged that youths in CAI-Baixada "do not have the use of necessary items for personal cleanliness (soap, a place to bathe, towel, toothpaste, toothbrush, etc.)," lacked clean clothing, did not receive needed medications, and did not all have mattresses and bedding.109 In fact, the director of CAI-Baixada wrote to DEGASE's central office in February 2005 saying, "We face difficulties in obtaining supplies of all kinds for the adolescents' personal hygiene."110

Clothing is changed once a week in Padre Severino and other detention centers. Silvia R. described what this meant in the close quarters of a detention center:

Their clothing takes on a revolting smell. They stay in those clothes. They sweat. They stay in dirty rooms, a lot of them in each room. They start to reek. So the guards call them, "You stinking bunch, you filth."111

Some youths in CAI-Baixada go barefoot because the center does not have shoes or sandals for them, the public defender's office reported, characterizing this situation as "not rare."112 And when some of the parents we interviewed tried to bring their children clothing and other items, their children did not always receive what they brought. "They didn't give him his clothes. They didn't give him many things we brought," said Gerson J., the father of an eighteen-year-old held in Santo Expedito until February 2005.113

As one consequence of the lack of hygienic conditions in Padre Severino and other detention centers, we heard reports of skin conditions likely caused by scabies and other parasitic diseases, which the public defender's office describes as "constantly" present in Rio de Janeiro's detention centers.114 "Many get itchy sores," Silvia R. told us. "They stay there in those dirty cells, wet too." She told us that she brought her son a special antibacterial soap so that he would not get the condition. 115 André S. gave a similar account. When he was in Padre Severino, he said, "There were many people with itches. They stayed separated from the rest.... I still have marks here on my feet, some little black bumps that don't go away."116 Marcos G., in Santo Expedito when we interviewed him in May 2005, reported that his hands itched. He pointed out tiny bumps on one hand. "Many people have them," he said. He told us that he had not received treatment for the condition.117

Trash, standing water, and weeds covered a basketball court in Santo Expedito when Human Rights Watch inspected the center in July 2003.

© 2003 Stephen Hanmer/Human Rights Watch.

In May 2005, Santo Expedito's basketball court showed some improvements: The backstop had been replaced and the concrete painted. Trash still littered the edge of the court.

© 2005 Michael Bochenek/Human Rights Watch.

VII. The Inadequacy of Current Monitoring Efforts

As a general rule, many abuses in juvenile detention centers occur because they are closed institutions subject to little outside scrutiny. Beatings and other cruel and degrading treatment are the product of a systemic failure of accountability. In recognition of this fact, international standards call for independent, objective monitoring of juvenile detention centers as a critical safeguard against abuses in detention.118 Abuses are less likely if officials know that outsiders will inspect their facilities and call attention to abuses. Regular, guaranteed access to juvenile detention facilities by a variety of outside monitors – public defenders, prosecutors, judges, national and international human rights groups, and legislative commissions – can play an immensely positive role in preventing or minimizing human rights abuses.

The State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth, the secretariat to which DEGASE now reports, has taken several encouraging steps in recent months. After it received reports from the State Council for the Defense of the Child and Adolescent of abuses in Padre Severino, it initiated its own inquiry and eventually ordered the removal of the director at the center along with several guards.119 More recently, it has suggested that it will propose the creation of a juvenile detention Inspector General's Office that is independent of DEGASE.

Without independent monitoring, followed by effective administrative sanctions and prosecution in appropriate cases, the kinds of abuses we describe in this report and our previous report will continue unchecked.

Impunity

In our December 2004 report, we found that most detention centers fail to investigate complaints of abuse and that administrative sanctions are rarely imposed in practice. No authority we spoke with had heard of a guard being convicted for abusive conduct.120

Independent research efforts by the Committee for the Monitoring of the Juvenile Justice System of the State Council for the Defense of the Child and the Adolescent, the State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth, the public defender's office, the Center for Justice and International Law, and DEGASE itself found only five criminal cases that were ever brought against guards and other DEGASE staff for abuses against youths.121 Only one such case, dating from 1994, ended in conviction and imprisonment. One of those convicted in that case, Jurandir Rodrigues da Costa, has avoided serving the sentence of four years and one month that he received.122 Four cases are still thought to be pending – one dating from 1999, another from 2002, and two from August 2004.

Judge Vianna cited the single case of conviction and imprisonment as an indication that the juvenile justice system has accountability mechanisms.123 However, the fact that there is only one case of conviction and imprisonment for abuse after well over a decade of regular credible allegations of such incidents leads to the opposite conclusion – that state authorities have systematically failed to investigate and punish cruel and degrading treatment and other abuse. Impunity is the rule in juvenile detention centers, something that is not likely to change unless independent monitoring mechanisms are created, reformed, or reinvigorated.124

DEGASE's Inspector General's Office

The lack of effective internal monitoring is due in part to the fact that DEGASE's Inspector General's Office reports to the department's director general and thus has no independence. As State Undersecretary for Childhood and Youth Evandro Steele put it, "This is wrong. Me investigate myself? That does not work."125 According to Undersecretary Steele, the director general of DEGASE has the authority to appoint and remove his inspector general, and any such appointment only requires the approval of the state governor.126 The office's lack of independence means that it is unable to monitor the department effectively.

The State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth, the secretariat that now has responsibility for DEGASE, is preparing a proposal that would remove the Inspector General's Office from DEGASE and place it instead as a separate, autonomous entity within the secretariat. This proposal shows promise, particularly if an independent Inspector General's Office is given full access to places of detention and all investigatory powers necessary to carry out its mandate. It should also be given the authority to receive complaints directly and to refer cases to the public prosecutor's office. In addition, it should be required to report its findings publicly.

The Absence of Monitoring by State Prosecutors

Even an independent inspector general's office can only do so much to combat impunity if state prosecutors do not also exercise their own monitoring role. Despite having the most important and most expansive oversight mandate in the juvenile justice system, the state prosecutor's office has neglected this role, focusing almost entirely on the prosecution of adolescent offenders.

Article 201 of the Statute of the Child and the Adolescent places various supervisory and investigatory legal powers and duties with the state prosecutor's office. In particular, under article 201(XI), government prosecutors have the authority "to inspect the public and private service entities and programs that are referred to in this Law, adopting promptly the administrative or judicial measure necessary for the removal of irregularities that are verified."127 In exercising this function, representatives of the prosecutor's office have "free access to every location where children and adolescents are found," a fact that state prosecutors confirmed when they met with us.128 Among other measures state prosecutors may take in response to violations, they may bring a "public civil action" (ação civil pública), a proceeding roughly equivalent to a class action lawsuit against the state.129

But prosecutors rarely exercise their monitoring function. We asked Marinete Laureano, director of Santos Dumont, if prosecutors ever inspected her detention center. "That would be tough to see," she replied, meaning that such a thing happened rarely, if ever.130 Attorneys with the public defender's office expressed similar doubts that prosecutors ever conducted inspections. "Our team goes to these centers [João Luiz Alves and Santos Dumont] each week, and we have never seen them there," Eufrásia Souza told Human Rights Watch.131 In fact, the state prosecutor's website contains inspection forms for adult prisons, shelters, and police holding cells but no form for inspections of juvenile detention centers, suggesting that prosecutors do not carry out such inspections as a matter of routine.132

The public prosecutor's office is aware of allegations of abuse in Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention centers. Human Rights Watch representatives have met with prosecutors three times in the last two years, most recently in May 2005. And Márcia Castro, a lawyer at the Bento Rubião Foundation Center for the Defense of Human Rights, commented, "We have already sent accusations [concerning DEGASE] to the state prosecutor's office, but I did not see much action taken."133

Human Rights Watch is aware of only two instances in recent years in which prosecutors attempted to inspect a juvenile detention center for cases of violence. One of these was in November 2002, when state prosecutors visited Santo Expedito at the invitation of the public defender's office after a major rebellion left one youth dead, several injured, and most of the center in flames.134 The prosecutors never followed up on their visit and have not returned to the center since that time to check for cases of abuse. "I ask every time I go there [to Santo Expedito]. They have never come," said Fabrício El-Jaick, an attorney with the public defender's office.135

The second instance, as recounted in our December 2004 report, was a surprise inspection of Padre Severino in July 2003, leading to the closing of a cramped, windowless punishment cell.136 This surprise inspection was a rare and welcome step toward accountability. Regrettably, no similar step has been taken by the state prosecutor's office since that time.

State prosecutors are now gradually undertaking some monitoring efforts. In what one prosecutor described as "the inauguration of a new era," a team from the state prosecutor's office visited each juvenile detention center at least once in 2004. The teams inspected the physical conditions of each facility and the educational program each offered. It found particular faults with the education offered at the centers; as another prosecutor noted, "There is a failure" in that area. However, as prosecutors themselves recognized, the 2004 visits were not designed to investigate potential cases of abuse. Violence-related inspections are still carried out only in response to specific complaints, usually from family members of youths in detention.137

We urged prosecutors in May 2005 to improve upon these efforts by systematically including investigation of acts of violence and other abuses against youths in detention. In response, prosecutors told us that "there is a possibility" that future inspections would include monitoring of abuses.138

Such a step would be a welcome one. Until now, the prosecutor's office has been conspicuously absent throughout the current crisis in Rio de Janeiro's juvenile detention system. The public defender's office has tried to fill the gap, filing public civil actions on behalf of youths in each of the five detention centers, but judges have questioned their standing to bring such actions. In addition to taking on a stronger monitoring role of its own, the state prosecutor's office should intervene in these public civil actions to resolve any question of standing and allow them to be heard on their merits.

Weak Oversight by the Juvenile Court

The branch of the juvenile court that deals with juvenile offenses, the Segunda Vara da Infância e da Juventude, is the authority responsible for judicial oversight of juvenile detention centers. Judge Vianna told us officials from the court enter each of the state's juvenile detention centers on a monthly basis and submit reports of each inspection to him. He showed us two recent reports on CAI-Baixada. The bulk of each report consisted of statistical information such as the number of youths in detention and the number and type of professional staff. Each report had a section setting forth current problems at the center. The later of the two we saw noted, for example, that the center had a shortage of laundry detergent and that staff had warned that there was a risk of escape attempts by youths.139

Neither report had a section on violations by guards, although Judge Vianna assured us that his office investigates the possibility of guard abuse. Later in our interview, however, he dismissed out of hand the possibility of beatings by guards in all but the most isolated of cases. The idea was "fantasy," he told us, insisting that systematic abuses "do not exist."140

Our interview with the juvenile court office responsible for the inspections explained the lack of information on abuses in the reports we saw. Two teams conduct visits every other month, not every month, we learned from a court commissioner. "One team looks at the physical installations, and the other looks more at the compliance with the socio-educational measures and activities," the commissioner told Human Rights Watch. When we asked whether a specific team investigated cases of abuse, the commissioner replied, "No," but went on to tell us that either team could look into reports of abuse. The commissioner told us that the teams do not look into the possibility of abuse unless they have received a specific complaint.141

We asked state prosecutors whether court officials forward complaints of abuse uncovered in their inspections. "An allegation of an abuse, a guard's punishment that got out of hand – this does not usually come to us from the commissioner. Very rarely. It usually comes through parents, organizations, or even the youths themselves," prosecutors told us.142

Other detention center officials reported that juvenile court officials inspected their centers. Marinete Laureano, director of Santos Dumont, told Human Rights Watch that court officials regularly inspect her center; she said that they talked with youths and toured the grounds and housing units.143 But a former guard at another detention center took issue with this description of inspections by juvenile court officers. "Sure, they come," he said. "They sit and have a cup of coffee with the director, and then they go off and write their report."144

Even if juvenile court officials made rigorous periodic inspections that included confidential interview with youths, it is unlikely that youths would report beatings and other abuses to representatives of the authority responsible for sentencing them to detention. Rigorous judicial inspections are an important element in monitoring juvenile detention facilities, but they cannot be the only such mechanism.

The State Public Defender's Office

Public defenders visit nearly all juvenile detention centers on a weekly basis. 145 There is no other autonomous government entity that is present with such frequency in the state's juvenile detention system. As a result, public defenders' knowledge of the system is unparalleled, and they enjoy a high degree of trust from detained youths.

A chronic staffing shortage inhibits the office's work. There are currently so few public defenders that approximately twenty of Rio de Janeiro's judicial districts lack a public defender.146 In practice, this has meant that outside the city of Rio de Janeiro some youths are tried and sentenced without legal counsel.147 Within the metropolitan area as well as in the interior of the state, public defenders are usually not able to assist accused youths when they are held and questioned at police stations even though in theory a lawyer should be available to youths at every step of the legal process after they are apprehended. In fact, it is not uncommon for no defense counsel to be present at an accused youth's first meeting with public prosecutors. "It would be better to have a defender right from the DPCA [Police Precinct for the Protection of the Child and Adolescent] also so as to establish a relationship," Marcia Castro, lawyer at the Bento Rubião Foundation told us. "The adolescents have to have confidence in you. If not, they will not tell you everything. I believe that having this [presence of a defender from the start] would change many things."148

The State Council on the Defense of the Child and Adolescent

In September 2004, the Commission for the Monitoring of the Juvenile Justice System of the State Council for the Defense of the Child and the Adolescent, headed at the time by lawyer Carlos Nicodemus of the local human rights organization Projeto Legal (Legal Project), conducted an inspection of Padre Severino. The commission's findings included allegations of youth mistreatment by guards, leading the State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth to instruct DEGASE to remove the director of Padre Severino and several guards in October 2004.149 At the this writing, however, no one implicated by the September 2004 report has been charged criminally. Moreover, one of the guards implicated in the abuses had been facing prosecution for torture since 2002.150

The State Council for the Defense of the Child and the Adolescent, which includes members of civil society as well as representatives of government agencies, has the potential to promote accountability and reform within DEGASE. Its counselors have guaranteed access to DEGASE's centers and may perform inspections at will. Its Commission for the Monitoring of the Juvenile Justice System was formed precisely to be an oversight mechanism. The results of its September 2004 inspection served as an important tool for accountability. Nevertheless, the council lacks enforcement powers; it must rely on the state secretariat or the public prosecutor's office to act on its recommendations.

The Barriers to Independent Monitoring by Civil Society

It is often difficult for members of civil society to have access to juvenile detention centers and obtain other information about them. "The state wants to treat the penitentiary system and the juvenile detention system alike as a black box," Anderson Sanchez, a representative of the Penitentiary and Socio-Educational System Employees' Union, commented to Human Rights Watch, "and we have to fight against that."151

These barriers begin with restrictions on parental visits, which are usually permitted once every week. Visits take place under tightly controlled conditions, many of which have a valid security rationale.152 Among the rules parents and youths must observe, however, is one that forbids youths from lifting their shirts during a visit. It is difficult to imagine the security rationale for this rule, particularly because visitors have already undergone a full strip search before entering the facility. Silvia R., a mother of a youth recently detained in Padre Severino, was convinced the rule was used to hide evidence of physical abuse. "It's so we cannot see any marks that could be there [on their bodies]," she said.153

Parents also criticized the limitation of one parental visit per week. While the primary purpose of these visits is not to serve a monitoring function, parents suggested that more frequent visits could be both an additional check on abuses and also reinforcement for the rehabilitative message that the detention system would ideally provide. Mônica Suzana, a co-coordinator of Moleque, a movement of mothers of detained youths, commented:

Right when our children make a mistake and need us the most, right then we can barely be near them anymore. The state needs to let any mother's movement be its ally. We [mothers] do not want war. We want to work together to recover those kids. They keep us away so they can do those absurd things because they know that if we were beside them, we would keep a lookout.154

DEGASE no longer has any formal relationship with any mothers' association, although for a time in 2002 another mothers' group made presentations to youths in detention. Even during that time, said Rute Sales, the other co-coordinator of Moleque, "When we [mothers] entered, we were always viewed very badly."155 In a subsequent conversation with Human Rights Watch, she added, "Mothers are the ones with the most legitimate desire to help in the system, but even so their participation is discouraged."156

Human Rights Watch entered all five juvenile detention centers in July and August 2003 with judicial authorization. The State Secretariat for Childhood and Youth, the secretariat to which DEGASE now reports, authorized our return inspection in May 2005. Nevertheless, DEGASE officials barred us from entering its facilities on May 24, 2005, after we had visited three centers – João Luiz Alves, Santos Dumont, and Santo Expedito. Human Rights Watch researchers met with DEGASE's chief of staff that afternoon and showed him their authorization, but he refused to accept it. The chief of staff called them at the end of the day, claiming that that the State Secretary for Childhood and Youth had revoked the authorization of entry.157

When we met the next day with José Maurício Gonçalves Costa, chief of staff at the secretariat, he told us that the DEGASE chief of staff had misrepresented his conversation with the secretariat. Hearing of the DEGASE official's claim that the secretary had revoked our authorization, he responded, "That's a lie."158

We also sought authorization from Judge Vianna for entry into the remaining facilities. He initially refused our request, saying, "You went to the secretariat when you should have come to me first, and now I won't permit you to enter." Later in our conversation, he told us that he would have to send our request to both DEGASE and the state prosecutor's office. "I cannot authorize anyone's entry against DEGASE's will. They also have to approve it," he explained. When we expressed skepticism that any human rights group could meet this standard for entry into juvenile detention centers, he replied, "I have never seen DEGASE refuse entry to anyone who comes in with an open spirit of collaboration, but if you go in to do a report against someone, against the state, then it gets difficult."159

The state prosecutor's office replied that it saw "no problem" with Human Rights Watch's request for entry.160 At this writing, Judge Vianna has not acted on the request.

In contrast to Rio de Janeiro, the state of São Paulo now gives a mother's association (Associação de Mães e Amigos de Crianças e Adolescentes em Risco, AMAR) and four other groups from civil society free access – not limited to previously scheduled workshops and presentations – to all its juvenile detention centers, an important advance for the state's troubled juvenile detention system.161 The state of Pará guarantees representatives of nongovernmental Centers for the Defense of Children and Adolescents access to juvenile detention facilities; the Pará state constitution provides for such access to "each and every legally constituted entity connected to the defense of the child and the adolescent."162 Internationally, many nongovernmental organizations, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and local groups, conduct independent monitoring in detention centers. The International Committee of the Red Cross carries out a similar function with respect to detention conditions of prisoners of war.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Michael Bochenek and Fernando Delgado, based on nine months of research, from September 2004 to June 2005, by Fernando Delgado in Rio de Janeiro. Michael Bochenek is counsel to the Children's Rights Division of Human Rights Watch. Fernando Delgado is a 2004 A.B. graduate of Princeton University and the Henry Richardson Labouisse '26 Fellow for Human Rights Watch in Rio de Janeiro for 2004-2005.

Lois Whitman, executive director of the Children's Rights Division; Joanne Mariner, deputy director of the Americas Division; Wilder Tayler, legal and policy director of Human Rights Watch; and Iain Levine, program director of Human Rights Watch, edited the report. John Emerson designed the maps. Fitzroy Hepkins, Andrea Holley, Veronica Matushaj, and Ranee Adipat provided production assistance. Reginaldo Alcantara translated the report from English into Portuguese.