Reading between the "Red Lines" The Repression of Academic Freedom in Egyptian Universities

| Publisher | Human Rights Watch |

| Publication Date | 9 June 2005 |

| Cite as | Human Rights Watch, Reading between the "Red Lines" The Repression of Academic Freedom in Egyptian Universities, 9 June 2005, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/42c3bd040.html [accessed 5 June 2023] |

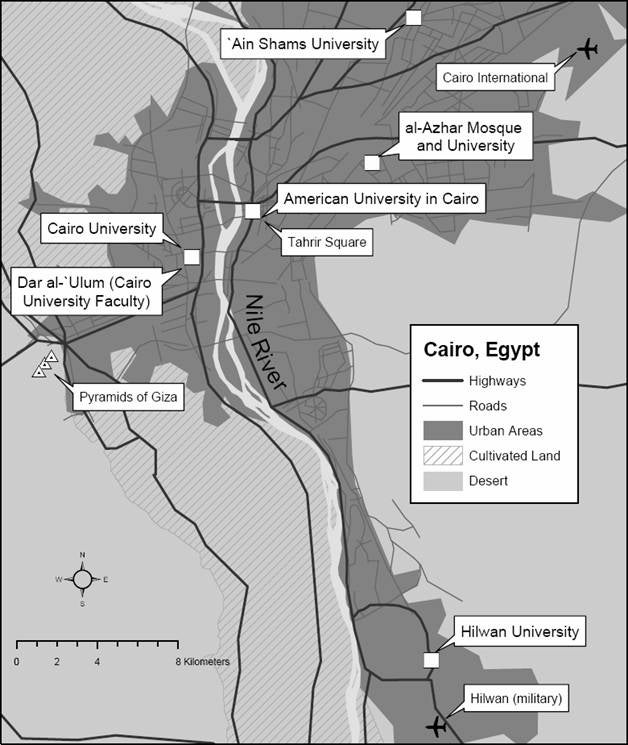

| Comments | This report details ongoing government restrictions on classroom discussions, research projects, student activities, campus demonstrations and university governance. The report addresses conditions in public institutions including Cairo, Alexandria, 'Ain Shams, and Hilwan Universities, and private institutions like the American University in Cairo. |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Acronyms

AUC – American University in Cairo

CAPMAS – Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics

CESCR – Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

ICCPR – International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICESCR – International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

IRC – Islamic Research Council

LE – Egyptian Pound

MESA – Middle East Studies Association

NDP – National Democratic Party

UDHR – Universal Declaration of Human Rights

UNDP – United Nations Development Programme

I. Summary

Recent studies of the Arab world have turned a spotlight on the poor state of its university education. In 2003, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Arab Human Development Report focused on education in the region. The report concludes, "Knowledge in Arab countries today appears to be on the retreat.... Continuing with this historic slide is an untenable course if the Arab people are to have a dignified, purposeful and productive existence in the third millennium."1 One important reason for this decline is the lack of academic freedom on university campuses.

Conditions at universities in Egypt, historically a leader in education in the Arab world, exemplify the problem. On a mission to Egypt, Human Rights Watch found that academic freedom violations pervade the country's system of higher education. Since the early 1990s, Egyptian academics have faced public condemnation, judicial convictions, physical violence, and other forms of intimidation from both government officials and private groups and individuals, particularly Islamist militants. Among the most publicized cases is that of Cairo University professor Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid, who had to flee the country after being declared an apostate by a national court for his scholarship on the Quran. American University in Cairo (AUC) professor Samia Mehrez had a course book with sexual content censored and suffered attacks in the press and parliament. And Saadeddin Ibrahim, an AUC sociologist who had conducted research projects on controversial political and religious subjects for an independent research center, endured three years of trials and prison time before being acquitted. Although some of these events date back several years, they remain vivid in the minds of Egyptian academics.

The assault on academic freedom is more subtle, but more extensive than the headline cases indicate. Repression by government authorities and private groups has affected every major component of university life, including the classroom, research, student activities, and campus protests. Censorship stops professors from teaching certain books. Permit requirements for surveys block research in the social sciences. University officials and police limit student activities outside the classroom. State security forces often respond violently to campus demonstrations. Such widespread abuses stifle debate and the free exchange of information, thus preventing Egyptian students from receiving a quality education and Egyptian scholars from advancing knowledge in their fields.

State and non-state actors alike contribute to the poor state of academic freedom in Egypt. State security forces illegally detain and sometimes torture activist students who run for student union or who demonstrate on campus. The government applies additional pressure through appointed deans and restrictive laws. Most of the non-state interference comes from Islamist militants, whose political activism is religiously driven. This group intimidates professors and students through a variety of tactics, including litigation and physical assaults. One professor accused Islamist militants of creating an "atmosphere of terror" in which scholars worry their lectures or research will be condemned as blasphemous. In some cases, these sources of repression feed on each other. Academics appease Islamists because they fear increased state repression and accept state repression because they fear the wrath of Islamists.

Years of repression have created an environment of self-censorship in Egyptian universities. Professors and students acknowledge that there are certain subjects – chiefly politics, religion, and sex – that they will only discuss in a limited way. They say they feel free to say whatever they want, but only provided they do not cross one of the taboo "red lines." Self-censorship can be as damaging to higher education as direct repression. It is also a sign that many Egyptian academics no longer resist, or sometimes even recognize, violations of academic freedom.

Institutional restrictions have exacerbated the academic freedom violations on national campuses, contributing to the deterioration of quality education in Egypt. The state controls faculty appointments and promotions, infringing on university autonomy. A rigid approach to learning discourages creativity throughout the university system from entrance exams to Ph.D. programs and deprives students of the power to choose freely their academic pursuits. Inadequate funding has caused professors to seek alternative places of employment and led to decrepit facilities. The Ministry of Higher Education has developed a plan for future reform, but it is too soon to determine if the government has the money and the will to implement it.

The pervasive violations by state and non-state actors and fearful responses by academics have created a stagnant educational environment. Professors and students repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that Egypt's universities are no longer centers of creative thinking. Higher education has become largely rote, and people take the safe path. "It's an unexciting environment. It is not stimulating on a daily basis.... Most free spirits are seething with frustration," said Ann Radwan, executive director of the Binational Fulbright Commission in Cairo and long-time observer of Egyptian academia. "Fear leads people to think it's better to have continuity, to keep things quiet."2 The general sense of apathy not only interferes with the quality of education but also affects society at large. Universities should serve as the training ground for a country's leaders as well as a forum for discussing solutions to its problems. In the present atmosphere, they fail to do both.

This report presents the findings of a three-week research mission to Egypt from February 12 to March 5, 2003, supplemented by telephone interviews and archival research from 2003 to 2005.3 Human Rights Watch interviewed twenty-seven professors and sixteen students from Cairo and Alexandria and had access to published accounts summarizing the experiences of many others. It also met with Egyptian government officials, including the minister of higher education and a state censor, and about two dozen lawyers, journalists, NGO representatives, and foreign diplomats who have worked on academic freedom issues. In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed international and Egyptian laws and university histories. Research focused on Cairo University and the AUC, Egypt's oldest and most prestigious public and private universities, respectively. It also involved interviews with people from 'Ain Shams, Alexandria, and Hilwan universities. This scope covers the most famous and highly regarded academic institutions in the country.

Since the Human Rights Watch mission in 2003, Egyptian professors and researchers have taken some steps toward promoting academic freedom. In fall 2003, a group of professors established the Ninth of March Committee for the Independence of Universities. The committee is named for the date in 1932 on which Rector Ahmed Lutfi al-Sayyid of Cairo University resigned to protest the government-ordered dismissal of renowned professor Taha Hussain. The committee has raised awareness of the lack of academic freedom at annual events on March 9 and has sent letters to the university administration to protest interferences by the security police in education.4 More recently, the Egyptian Association for Support of Democracy published a report on the October 2004 student elections in four universities, and Cairo University historian Raouf Abbas published an autobiography that includes anecdotes about government interference in university life.5 Such actions represent important initiatives by members of the academic community on behalf of academic freedom.

Professors and students protest just outside the gates of Cairo University on February 22, 2003. The university's domed Great Festival Hall can be seen in the background.© 2003 Bonnie Docherty / Human Rights Watch

In addition to illuminating the troublesome state of Egyptian academia, this Human Rights Watch report explains how the restrictions on academic freedom violate international law. The principle of academic freedom derives in part from the internationally recognized right to education, which is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which Egypt has ratified. According to the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR), "the right to education can only be enjoyed if accompanied by the academic freedom of staff and students." Academic freedom encompasses both rights for individual members of the university community, such as freedom of opinion, expression, association, and assembly, and autonomy for institutions, which must be free from state interference with the university's educational mission.

In its pervasive repression of academic freedom, Egypt violates international law. The government stifles people seeking to participate, as individuals or groups, in all aspects of academic life. It maintains police, administrative, and legal control over the universities, depriving them of institutional autonomy. Egypt should move to correct these violations and infringements through legal and administrative means. It should also prevent attacks on academic freedom by private individuals or groups.

The international community, meanwhile, should recognize the systemic problems with higher education in Egypt and find constructive avenues to press for change. While some of the most egregious cases already have attracted outside attention, foreign governments and media have not always acknowledged the seriousness and pervasiveness of academic freedom violations in Egypt. In its 2002 Human Rights Report, the U.S. Department of State, for example, condemned the prosecution of Saadeddin Ibrahim and its "deterrent effect" on freedom of expression. It stated incorrectly, however, "The Government did not restrict directly academic freedom at universities."6 The 9/11 Commission Report recommends that the United States spend money to "rebuild scholarship, exchange, and library programs" and to buy textbooks in the Arab world.7 While financial assistance for resources, technology, and facilities could help remedy existing deficiencies, such funds will be wasted if the restrictions on academic freedom detailed below are not addressed. Large donors to Egypt, such as the United States and the World Bank, should better familiarize themselves with the academic freedom violations in that country and use their leverage to help end them.

II. Recommendations

Human Rights Watch makes the following key recommendations to promote and protect academic freedom in Egypt. Chapters five through seven contain more detailed recommendations at the end of each section.

1. The Egyptian government should cease using state security forces to intimidate and physically abuse professors and students.

State security forces have created a climate of fear on university campuses. They observe selected classes to keep discussions from crossing red lines and sometimes beat students seeking to express themselves by means of posters or speeches. Police detain, physically abuse, and in at least one case allegedly have tortured candidates for student union elections. They also sometimes respond with excessive force to peaceful demonstrations. Professors and especially students described the police presence as one of the major obstacles to academic freedom in higher education. The government should forbid security forces from playing any role on campus other than the strictly limited one of protecting public order.

2. State-appointed deans should cease interfering in academic freedom.

Since 1994, public university deans have been appointed by rectors, who are in turn appointed by the state. As implemented, this process gives the state too much control over internal university matters and favors for deanships professors who support the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP). Such deans frequently interfere with academics' freedom of opinion and expression. Professors and students told Human Rights Watch of cases in which deans monitored classroom discussions, cut off exchanges on controversial subjects, denied politically active professors contact with students, and blocked leftist and Islamist students from running for student government. Human Rights Watch was told that, in many cases, deans also closely scrutinize student activities, including student clubs and other forms of association on campus, and stifle expression that threatens to cross red lines. Deans must resist political pressures and act according to academic rather than political or other criteria.

3. Egyptian legislators should amend or abolish several laws that interfere with academic freedom.

Besides government security forces and state-appointed deans, Egyptian laws violate the principles of academic freedom. Law No. 20/1936, which allows censorship of all imported course books, should be abolished. Presidential Decree No. 2915/1964 establishes permit requirements for social science research that effectively block research on controversial topics and should be amended. The University Law of 1979 gives state-appointed deans unwarranted power over student activities and should be amended to allow the formation of political and religious clubs and to remove the "good conduct" requirement for student union nominees. Finally, the Emergency Law has been used to authorize arbitrary detention and unfair trials that intimidate and punish academics who cross red lines. It should be repealed.

4. Egyptian authorities should ensure that academic freedom is protected from threats and acts of intimidation by Islamist militants.

International law holds states responsible for the actions of their citizens and residents as well as themselves, and in this case, Egypt is responsible for protecting its academics from abuse by Islamist militants. The government should end its own violations, such as a censorship regime, that provide poor role models to private actors. State representatives should also oppose threats from individuals and groups on campus and in the press and protect academics' rights to teach and research subjects of their choosing.

5. Private individuals, groups, and associations in Egypt should actively resist Islamist militants' attempts to restrict academic freedom.

Islamist militants have used physical, legal, and media attacks to stifle Egyptian intellectuals. In particular, they intimidate professors and students so that they are afraid to assign course books or research topics dealing with religion or sex. Egyptians who oppose such activities – including members of the media – should speak out publicly against them.

6. The international community should recognize the systemic problems in higher education in Egypt and use its leverage to combat them.

Members of the international community, including the United States and World Bank, have promised or been asked to fund education in Egypt. Such funding may enhance resources, technology, and facilities, but the system of higher education will not flourish without the elimination of pervasive restrictions on academic freedom. Donors should use their diplomatic and financial leverage to push for such change. The UNDP should also continue to monitor education in the Arab world and call attention to violations of academic freedom.

III. Academic Freedom: Definition and Legal Protections

Academic freedom gives members of the academic community the right to conduct and participate in educational activities without arbitrary interference from state authorities or private individuals or groups, including popular political, religious, or other social movements. It is a broad principle that protects professors and students and applies to the complete range of academic pursuits – formal and informal, inside the classroom and beyond. International law requires states to respect academic freedom, a principle based on a series of basic and widely accepted human rights. In many countries, domestic law provides explicit protection for academics. Egypt is bound to ensure academic freedom for its citizens by both the treaties it has ratified and its constitution, which includes safeguards for the relevant rights.

Right to Education

The principle of academic freedom stems in part from the internationally recognized right to education. This right is enshrined in Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 (UDHR)8 and Article 13 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights of 1966 (ICESCR) to which Egypt has been a state party since 1982.9 According to the official commentary on the ICESCR, Article 13(2) requires education to "include the elements of availability, accessibility, acceptability, and adaptability." This means there must be a sufficient number of institutions; these institutions must not discriminate and must be physically proximate and economically affordable (except for higher education, which need only be accessible "on the basis of capacity" of the individual); the education must be appropriate for students and "of good quality"; and it must be flexible enough to respond to different students and times.10

These conditions alone, however, do not guarantee the right to education. The Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR), which interprets the ICESCR, has stated that "the right to education can only be enjoyed if accompanied by the academic freedom of staff and students."11 Academic freedom is particularly important in higher education. Its community of young adults and highly educated teachers and researchers includes individuals more inclined to be politically engaged and, therefore, likely to be attacked by intolerant authorities or private citizens.

The CESCR's definition of academic freedom consists of two parts. The first component relates to members of the academy – professors and students, as individuals or groups. In its comment on Article 13, the committee wrote,

Members of the academic community, individually or collectively, are free to pursue, develop and transmit knowledge and ideas, through research, teaching, study, discussion, documentation, production, creation or writing. Academic freedom includes the liberty of individuals to express freely opinions about the institution or system in which they work, to fulfill their functions without discrimination or fear of repression by the State or any other actor, to participate in professional or representative academic bodies, and to enjoy all the internationally recognized human rights applicable to other individuals in the same jurisdiction.12

According to this definition, academic freedom encompasses a series of other widely accepted human rights, including freedom of opinion, expression, association, and assembly. These civil and political rights are enumerated in the UDHR and legally binding on states parties to the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).13 Egypt ratified the ICCPR in 1982.

The second component of academic freedom relates to the universities themselves rather than members of the community. The CESCR's comment explains, "The enjoyment of academic freedom requires the autonomy of institutions of higher education."14 In order to serve as a forum where academics can freely exchange knowledge and ideas, universities must be independent of the state.

While governments are the primary protectors of academic freedom, CESCR also places duties on individuals and institutions. Members of the academic community have the "duty to respect the academic freedom of others, to ensure the fair discussion of contrary views, and to treat all without discrimination on any of the prohibited grounds."15 Universities, meanwhile, must be held accountable, especially for their management of state funding. "Given the substantial public investments made in higher education, an appropriate balance has to be struck between institutional autonomy and accountability. While there is no single model, institutional arrangements should be fair, just and equitable, and as transparent and participatory as possible."16 Academics and universities not only are beneficiaries of academic freedom, but also play an important role in ensuring its protection.

Rights Belonging to Members of the Academic Community

Freedom of Opinion

Freedom of opinion is the first building block of academic freedom. Education involves not only the acquisition of knowledge but also the development of ideas. The CESCR specifically mentions that academics are free to "develop ... ideas" and "express ... opinions."17 Without freedom of opinion, academia would produce only information with no interpretation or analysis. International law protects this right in the ICCPR, Article 19(1) of which says, "Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference."18 The right is absolute; the law prohibits interference under all circumstances.19

It can be difficult to judge whether a government or private actor has violated this right because that requires understanding what is in someone's mind. According to the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, "What exactly constitutes an impermissible interference with the freedom of opinion is not an easy matter to determine. In general, it is possible to speak of such an interference when an individual is influenced against his will and when this influence is exerted by threat, coercion or the use of force."20 Censorial pressures can also become routinized to the point where many people take for granted that certain opinions are unacceptable and fail to recognize unlawful restrictions on their academic freedom.

Freedom of Expression

Freedom of expression is an essential part of academic freedom because it allows for the exchange of knowledge and ideas. As the CESCR explains, academics are free to pursue this exchange "through research, teaching, study, discussion, documentation, production, creation or writing."21 Education is a collective as well as an individual undertaking, which depends on discussion and debate. In the classroom, professors need freedom to teach and students to ask questions and try out ideas. In research, academics must have access to knowledge provided by others and the ability to present their own scholarship publicly. Freedom of expression is also important in less formal forums, such as student clubs and campus demonstrations.

International law protects freedom of expression. Article 19(2) of the ICCPR states, "Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include the freedom to seek, receive and impart information of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice."22 Expression may not be limited by content or form. The provision also encompasses freedom of information, which protects an individual's right actively to seek information.23

International law allows freedom of expression to be restricted only in certain circumstances. According to Article 19(3), restrictions must be "provided by law," meaning they must be laid out in advance in statute or common law, and they must be "necessary: a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others; b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals."24 To be necessary, a restriction "must be proportional in severity and intensity to the purpose being sought and may not become the rule."25 International law prohibits pre-publication censorship; academics should have the opportunity to present their work before the state rules it impermissible.26 Although the law allows some limits to be placed on freedom of expression, they are appropriate only under exigent circumstances and must be interpreted narrowly.27

Freedom of Association

University life is not confined to the classroom and library or laboratory. It also includes gatherings, formal and informal, of members of the community. In its discussion of academic freedom, the CESCR specifically mentions the freedom "to participate in professional or representative academic bodies."28 International law protects such formal gatherings under freedom of association. According to Article 22 of the ICCPR, "Everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests."29 People have the right to form associations, and those associations must be free to act on behalf of their members.30 Although the article only names trade unions, freedom of association extends to groups of varying forms and purposes. "Religious societies, political parties, commercial undertakings and trade unions are as protected by Art. 22 as cultural or human rights organizations, soccer clubs or associations of stamp collectors. Moreover the legal form of an association is basically unrestricted," says a respected treatise on the ICCPR.31 On campus, therefore, freedom of association provides protection not only for teachers' unions, a type of trade union,32 but also for student unions and student clubs.

As with freedom of expression, the ICCPR allows for some limited restrictions on freedom of association. These restrictions must be "prescribed by law" and "necessary in a democratic society."33 "Necessary" again refers to proportionality. The addition of "in a democratic society" means the restrictions must "be oriented along the basic democratic values of pluralism, tolerance, broadmindedness and peoples' sovereignty."34 The permitted purposes for interference are essentially the same as in Article 19, except that "public safety" is added to the list.35

Freedom of Assembly

Freedom of assembly protects less formal gatherings on campus, most notably student and faculty demonstrations. According to the CESCR, academic freedom includes the "liberty of individuals to express freely opinions about the institution or system in which they work."36 One of the most common forums for expressing criticism of the government is a demonstration. Such gatherings are important for the political life of a country. In many countries, campus demonstrations are often the first sign of broader public discontent with the government policies. Article 21 of the ICCPR says, "The right to peaceful assembly shall be recognized."37 It gives professors and students the right to organize and participate in campus protests or other gatherings, as long as they are peaceful.38 The restrictions in Article 21 are almost identical to those in Article 22.

Rights Attached to the Institution: University Autonomy

Academic freedom extends not only to members of the academic community but also to educational institutions. According to the CESCR, university autonomy is a prerequisite for the exercise of professors' and students' individual rights. The committee defines autonomy as "that degree of self-governance necessary for effective decision-making by institutions of higher education in relation to their academic work, standards, management and related activities."39 Educational institutions should be able to make their own rules, administer themselves, and be free of control by state security forces. Autonomy is especially important for universities because they provide a forum for high-level debate on controversial topics. When they are subject to state interference, universities cannot serve as a safe place to engage challenging issues and intellectual life suffers.

Protection from State and Non-State Actors

Both government officials and private citizens and groups can threaten academic freedom.Under international law, states must take the necessary steps, including implementation of domestic legislation, to protect the rights that make up academic freedom from such threats. According to Article 2(1) of the ICCPR, "Each State Party to the Covenant undertakes to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status."40 The obligation to respect means states must not restrict rights, unless allowed under exceptions such as those found in Articles 19, 21, and 22. The obligation to ensure requires states to take proactive steps, when necessary, to guarantee the rights laid out in the covenant.41 The ICESCR, in which the right to education is enshrined, imposes a similar duty on states parties.42

International law also provides protection from actors independent of the state. The CESCR explains that individuals have the "duty to respect the academic freedom of others."43 The ICCPR places the burden for enforcing that duty on its states parties. Article 2's clause about ensuring rights means that states parties are obligated to prevent the violation of the covenant by private parties.44 The ICCPR explicitly lays out some actions states can take. The duty to ensure extends beyond the ICCPR's specific examples, however; states must take any actions necessary to guarantee third parties do not infringe on academics' legal rights.45

Self-Censorship

Direct repression of academic activities often leads individuals to censor themselves. Professors or students who have been repressed may be too frightened to exercise their rights again. Academics who observe the intimidation or punishment of their colleagues may choose not to test the system because of either fear or desire to avoid the bureaucratic hassle. Such a chilling effect on freedom of opinion and expression can be as great a threat to academic freedom as direct repression. It also discourages academics from participating in associations or assemblies. International law holds states responsible for preventing such interferences with academic freedom. According to Article 2 of the ICCPR, states parties must "ensure" that individuals have the rights laid out in the covenant. This obligation includes eliminating the repression that causes self-censorship and creating an environment in which members of the academic community feel free to exercise their rights.

Other Human Rights Protections

As outlined above, the principle of academic freedom encompasses a range of basic civil and political rights. The CESCR recognizes that the principle extends beyond the most obviously related rights and includes "the liberty ... to enjoy all the internationally recognized human rights applicable to other individuals in the same jurisdiction."46 States routinely ignore this provision. For example, they often use torture, arbitrary detention, unfair trials, and extrajudicial killings, all forbidden under international law, to silence their critics in the academy. Such actions represent both egregious abuses of universally accepted human rights and further restrictions on academic freedom.

Egyptian Law

In many countries, Egypt included, domestic law provides additional protection for academic freedom. The Egyptian constitution includes four articles that specifically discuss education. Article 18 states, "Education is a right guaranteed by the State. It is obligatory in the primary stage and the State shall work to extend [its] obligation to other stages."47 The constitution thus lays out the right to education, which, as discussed above, requires academic freedom. Article 18 concludes, "The State shall supervise all branches of education and guarantee the independence of universities and scientific research centres, with a view to linking all this with the requirements of society and production."48 This part of the article specifically mentions one of the requirements for academic freedom under international law, i.e. university autonomy. The article's call for state supervision and the mandate to link education to "society and production," however, could be read to authorize inappropriate limits on that autonomy. The remaining three education articles state that "Religious education shall be a principal subject in the course of general education" (Article 19), "Education in the State educational institutions shall be free of charge in its various stages" (Article 20), and "Combating illiteracy shall be a national duty for which all the people's energies should be mobilized" (Article 21).49 The latter two deal more with the right to education than academic freedom per se.

Other provisions of the Egyptian constitution protect the basic human rights essential to academic freedom. Article 47, which guarantees freedom of opinion and expression, says, "Every individual has the right to express his opinion and to publicise it verbally or in writing or by photography or by other means within the limits of the law. Self-criticism and constructive criticism is the guarantee for the safety of the national structure."50 The constitution also devotes an article to the protection of research. According to Article 49, "The State shall guarantee the freedom of scientific research and literary, artistic and cultural invention and provide the necessary means for its realisation."51 The constitution protects gatherings of academics with provisions related to assembly and association. Article 54 states, "Citizens shall have the right to peaceable and unarmed private assembly, without the need for private notice. Security men should not attend these private meetings. Public meetings, processions and gatherings are allowed within the limits of the law."52 Article 55 gives citizens "the right to form societies as defined in the law" as long as their activities are not "hostile to the social system, clandestine or have a military character."53 These articles cover the main components of academic freedom.

Despite constitutional protections that are generally in line with international law, Egypt has failed in practice to protect academic freedom. As will be shown below, the government has created and fostered a system of repression that stifles independent thinking and the free exchange of ideas. State and non-state repression as well as the self-censorship they cause pervade all areas of university life, including the classroom, research, student activities, and campus demonstrations.

IV. Background

Egypt has long been the intellectual and cultural center of the Arab world. It is home to al-Azhar, one of the oldest universities in the world, and was among the first Arab countries to establish a national secular university, almost a century ago. The latter, which became Cairo University, not only served as a model for other institutions in the region but also provided Egypt with scholars, political leaders, and opposition figures. Over the course of the twentieth century, Egypt's rapidly expanding university system faced periodic violations of academic freedom. In recent years, those attacks have become sometimes less obvious but more pervasive, threatening the freedom of individual academics and the autonomy of educational institutions in unprecedented ways. Whether Egypt's universities can continue to serve as intellectual role models for the region is seriously in doubt.

Rise of the National Universities

Egypt's intellectual leadership began with the founding of al-Azhar. Shi'a Fatimids established the religious university in Cairo in the tenth century; about two hundred years later, the Ayyubids under Saladin turned it into a Sunni institution. As Egypt became "the undisputed center of Islamic cultural and intellectual life,"54 students from across the Arab world came to al-Azhar to pursue Islamic studies. The formation of the Ottoman Empire eventually shifted political and cultural power to Istanbul,55 but al-Azhar remained (and remains) a significant force in the Islamic world, contributing to the resistance against Napoleon and providing religious leaders for the region.56

At the end of the nineteenth century, as part of a broad reform movement, the search began in Egypt for an alternative to al-Azhar's religious education. It was found wanting in its preparation of young Egyptians to meet the demands of the modern age. France and England had turned away from their traditionally Christian universities and either created new institutions or revamped and secularized the old ones.57 Inspired to modernize their own society, Egyptian politicians, aristocrats, and intellectuals started discussing options for forming a secular university in Cairo.

The minarets of al-Azhar tower over medieval Cairo. Founded in the tenth century, al-Azhar is the oldest university in Egypt and one of the oldest in the world. It continues to serve as a pan-Arab center for Sunni education. © 2003 Bonnie Docherty / Human Rights Watch

The Egyptian University, later renamed Cairo University, opened in 1908. It was created as a private, liberal arts college that sought "knowledge for its own sake."58 A university committee policy statement explained, "The firm foundations on which this great structure [of higher education] will be built can only be the introduction of the fields of knowledge which are now neglected in Egypt, like history, the arts, the humanities, and the higher sciences which elevate the individual and his people and make a nation great among nations."59 Research was an important part of Cairo University's mission. As one young professor explained, instead of merely presenting knowledge, "the university tries to discover the unknown, criticizes the achievements in learning, introduces arguments, replaces the old by the new, destroys one viewpoint and builds up another."60 These early mission statements provide an important point of contrast to the state of education in Egypt today.

The university's founders also recognized the need for autonomy. They sought to keep politics off campus and avoided hiring graduates of al-Azhar. They intended to have "no religion but knowledge."61 European professors dominated the first generation of faculty while promising Egyptian students were sent abroad to train for future teaching positions.

In 1925, three years after Egypt gained independence from Britain, the private university became part of the country's first state university. The original institution had insufficient funds and facilities to meet the growing demand for higher education. It was turned into a Faculty of Arts in an expanded institution that added a Faculty of Science and schools of law and medicine. As a condition of accepting reorganization, however, the private university demanded "as much autonomy from the minister of education as possible."62 The new university symbolically distinguished itself from al-Azhar, building its Western-style campus on the opposite bank of the Nile. A clock tower, rather than a minaret, dominated the campus. Although founded on a European model, the state university served as an important symbol of an independent Egypt, even appearing on national postage stamps.

Over the coming decades, Cairo University, then known as Fuad I University after the king and former rector, could no longer meet Egypt's needs for higher education. A second national university opened in October 1942. Originally named Faruq I University, it ultimately became Alexandria University. It followed Cairo's model, but made college education more accessible to Egyptians outside Cairo. Eight years later, the state added Ibrahim Pasha University, now 'Ain Shams, to its system. It was built in Cairo on the east bank of the Nile. By 1952, enrollments at the three state universities totaled 36,622.

After the fall of the Egyptian monarchy in 1952, the state popularized the national universities. Gamal Abd al-Nasser63 believed education should be open to the people and made universities free in July 1962. The result was an explosion in the number of students. During his years as president, Cairo University's student population grew two-and-a-half times, to 50,000. Nasser also shifted the emphasis of the national universities from liberal arts to science and technology and opened several institutes that provided more vocational training. Anwar Sadat, who succeeded Nasser in 1970, rejected his predecessor's economic views but generally continued his educational policies. The government continued to provide free access to the universities despite the fact that the emphasis on quantity of students led to a decline in quality of education. Expansion included the creation of Hilwan University, another institution in the Cairo area.

Over the past fifty years, the national university system has grown dramatically. Today it consists of twelve universities, spread geographically from Alexandria in the northwest to Suez Canal in Isma'ilia in the east to South Valley in Qina in the south. Branch campuses extend as far south as Aswan. According to the most recent available statistics, more than 1.1 million students are enrolled and about 200,000 graduate each year.64 In 1999-2000, 120,000 graduate students attended the national universities,65 and the number of faculty members reached 30,486.66 The system also includes a number of technical and higher institutes that provide vocational training in two to four years of study. The founders of Cairo University might be pleased that Egypt has a firmly established university system, but as this report will show, they would likely question the direction it has taken.

The American University in Cairo (AUC)

Shortly after the creation of the Egyptian University, a group of American missionaries founded the American University in Cairo (AUC). It began as a secondary school in 1920. In 1928, AUC graduated its first university class and enrolled its first female student. The school was modeled on other missionary schools in the Middle East, including the Syrian Protestant College, which later became the American University of Beirut. AUC, which moved into the Egyptian University's original home in Tahrir Square, offered an American-style liberal arts education in English. It added master's degrees in 1950.67

The school started small, but its influence grew as the United States became a world leader. In 1945, it enrolled 134 students, compared to Cairo University's 10,534. Statistics from around the same time show its student body consisted of forty-eight percent Christian, twenty-two percent Jewish, and thirty percent Muslim. After World War II, AUC became a more important player in Egyptian society. By the 1960s Muslim students outnumbered Christians. The school's graduates included Nasser's daughter and Hosni Mubarak's wife.

Located at the edge of Tahrir Square, this building houses the administration of the American University in Cairo. It served as the original home of Cairo University when it was founded in 1908. © 2003 Bonnie Docherty / Human Rights Watch

AUC is now the most elite university in Egypt. In fall 2003, it enrolled 3,963 undergraduates and 867 master's students. Of those, 89.3 percent were Egyptians.68 Although more integrated than previously into Egyptian society, it maintains its commitment to "the ideals of American liberal arts and professional education."69 Its mission statement says, "As freedom of academic expression is fundamental to this effort, AUC encourages the free exchange of ideas and promotes open and on-going interaction with scholarly institutions throughout Egypt and other parts of the world."70 AUC represents an alternative to Egypt's public university system. It provides a university education that is liberal arts-based, private, and international to students willing and able to pay tuition.71

Influence of Egyptian Universities

Egypt's secular universities began to influence politics and society shortly after their creation. During much of the twentieth century, they trained national leaders and provided forums for challenging that leadership. They also served as models for the new institutions of higher education springing up around the Arab world. The significance of these universities thus extended beyond their role as educators of Egyptian youth to shapers of Egyptian and Arab society.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Cairo University produced most of Egypt's professionals, politicians, and intellectuals. Its first rector later became King Fuad I, who reigned from 1917 to 1936. Between 1908 and 1952 almost all cabinet ministers who were not army officers graduated from the university. In addition to grooming the country's leaders, Cairo University was a national symbol at a time when Egypt was seeking its independence from Britain. "In France, with its prestigious grandes écoles, the University of Paris has not been nearly so vital for national life, nor has Harvard in the decentralized United States.... Oxford and Cambridge revived later in the [nineteenth] century, but they were still far less important on the national scene than Cairo University has been in Egypt," writes historian Donald Reid.72 Later in the century, Cairo University had to share its influence with new members of the state system. It also lost control of the national leadership; all three of Egypt's presidents since 1954 graduated from the Military Academy. While Cairo University's influence has diminished, it remains the most prestigious state university.

Historically Egypt's universities trained not only society's leaders, but also citizens willing to challenge the status quo. "Students from Cairo University ... were in the forefront of demonstrations in 1919, 1935, 1946, 1951, 1968, and 1972-73 which significantly affected the course of Egypt's history," Reid writes.73 These demonstrations usually criticized government policies, with students often focusing on what they considered the state's insufficiently militant policy toward Israel. The student movement peaked in the 1970s when leftists "fought against big government."74 In 1972, for example, more than three thousand students organized a sit-in at Cairo University to protest Israel's continued occupation of the Sinai Peninsula and to expose domestic problems. They printed leaflets, arranged for food and medicine to be distributed, and guarded the gates. "It was very organized. Egypt's intellectuals joined. It showed at the time students were a strong and organized force. [The movement] began to decline in the next couple years," said 'Imad Mubarak, a recent graduate and student activist, who now works at the Hisham Mubarak Law Center, named after his father.75 Engineering professor Saad el-Raghy remembers that the students in his faculty, who were "fed up" with Israel's presence in the Sinai Peninsula, threw stones and protested for hours. "Outside the gates it was like a battlefield," he recalled.76 The student movement has since lost much of its power due not only to infighting and generational changes, but also to repression.77 Nevertheless the memory of these days remains vivid in the minds of activists today.

As one of the oldest in the region, Egypt's state university system influenced similar institutions created later in the rest of the Middle East. The new universities that sprung up in the 1950s and 1960s looked to Egypt for guidance. "Cairo University ... became the prime indigenous model for state universities elsewhere in the Arab world," Reid writes.78 The other possible models – private American missionary schools, European colonial institutions, and Turkish universities whose significance faded with the fall of the Ottoman Empire – could not compete. Graduates of Egypt's universities became professors in the new foreign national universities. In 1974, for example, Egyptians represented seventy-one percent of the teachers at the eight-year-old Kuwait University. Egyptian universities opened satellite campuses in Khartoum, Sudan, and Beirut, Lebanon, in 1955 and 1960, respectively. Cairo University also attracted foreign students from around the region, who returned home with Egyptian training. Egypt continues to export academics, especially to the Gulf States, but today Egyptians express concerns that the influence flows in the other direction and is not friendly to academic freedom.

The History of Constraints on Academic Freedom in Egypt

Following on the heels of independence, the creation of a national university system gave hope to Egypt's academics. "Cairo University was thought of as an establishment where you could get a free and secular education apart from the complex of religious education at al-Azhar.... Cairo University was the beginning of new era.... [It] included a lot of space for people of different intellectual movements and backgrounds," said a professor who currently teaches at the university.79 Nevertheless, Egypt's secular universities faced threats to academic freedom from their earliest days. The challenges ranged from attacks on individuals to interference with university curriculum. While these largely isolated incidents did not significantly hinder the universities' influence at home and abroad, they foreshadowed the crisis that erupted shortly after Nasser's takeover of the state in the 1950s and the systemic and insidious repression that characterizes Egyptian campus life today.

In the first half of the century, university and state officials occasionally charged individual academics with blasphemy. In 1913, for example, the Egyptian University sent Mansur Fahmi to the Sorbonne to prepare for a position in its philosophy department. When the university administration learned Fahmi had written his dissertation on the condition of women in Islam, it said he had defamed Islam by accusing it of mistreating women and claiming that the Prophet Muhammad had written the Quran for personal reasons. The university stripped him of his promised professorship and confiscated copies of the thesis it had funded. He was banned from government posts and only returned to teaching seven years later.

More established scholars were also vulnerable. In 1926, eminent scholar Taha Hussain was at the center of "one of the most famous Arabic literary battles of the century."80 Al-Azhar condemned Hussain's book On Pre-Islamic Poetry as blasphemy and sparked a parliamentary debate. Unlike Fahmi, Hussain received support from the rector of his university and the incident died down. These threats to academic freedom demonstrate the difficulties Egypt's early academics faced trying to find a balance between secular and religious, and imported and more locally rooted approaches to education.

As the national university system began to grow in size and influence, a new government regime moved to co-opt it. Nasser, who took power in 1954, sought to shape higher education to serve his political purposes. He wanted academia to articulate an ideology for his brand of Arab nationalism and tried to enlist its support by controlling the campuses. "[F]reedom of thought, speech, and action was squelched. Police informers saturated the campus, and professors never knew the exact limits of permissible debate," Reid writes.81 One academic described the blow as a watershed in university history. "Academic freedom in Egypt ended in 1954 when the soldiers threw out the liberal professors and decided to turn Egyptian universities into a government bureau," said poet and former professor Ahmad Taha.82 Nasser also emphasized technical learning rather than "knowledge for knowledge's sake," Cairo University's original mandate. As a result, the Faculties of Engineering and Medicine replaced those of Law and Arts as the most prestigious and popular. While such disciplines are important fields of study, the head of state's influence over curriculum represented a loss of university autonomy. The universities' institutional problems started in this era, too. The numbers of students increased dramatically after Nasser eliminated tuition, but the quality of education declined because the faculty and facilities were not expanded at the same time.

Under Anwar Sadat, the universities reached their peak of activism and then were stifled by state repression. Sadat assumed control of Egypt after Nasser died in 1970. During the early years of his tenure, he eased restrictions on the academic community, removing police from campus, allowing professors to elect their deans, and facilitating more student activities. Afraid of the left's increasing influence, however, Sadat eventually cracked down on student activism with the University Law of 1979, which placed restrictions on student unions and other groups. He also surreptitiously encouraged Islamists in an effort to combat leftist influences; members of this group soon started pressuring their classmates to observe their interpretation of strict Islamic law. After signing the Camp David accords with Israel, Sadat's alliance of convenience with the Islamists ended. A squad of militant Islamists from the radical group al-Gihad assassinated him on October 6, 1981. Sadat not only left a legacy of direct state repression on campus but also unleashed sociopolitical forces that continue to challenge academic freedom today.

Egypt's universities now operate under the control of President Hosni Mubarak's government,83 and academic freedom violations continue. An Egyptian journalist from al-Ahram, the country's leading paper, told Human Rights Watch, "The government is against all freedom, whether left or right, the existence ... not [of] a particular group but [of] independent universities."84 The threats that universities face today may sometimes be less visible than under Nasser or Sadat, but as detailed below, they are pervasive and insidious. Incursions on academic freedom are destroying careers, restricting knowledge, and stifling creativity throughout Egypt's higher education system.

Egyptian Universities Today

The structure that represses academic freedom today has been built by state and non-state actors and by academics themselves. The Egyptian government uses police, political appointees, and laws to control all areas of university life. Islamist militants, meanwhile, have used physical violence and public attacks to shape the content of higher education. A climate of fear has led professors and students to censor themselves and to avoid discussion of certain subjects.

In Human Rights Watch interviews with professors, researchers, students, commentators, and officials, the existence of so-called "red lines" – taboo subjects – emerged as the central obstacle to academic freedom in Egypt. Egyptians use this term to describe boundaries that cannot be crossed on or off campus. Red lines encompass three controversial subject areas that are particularly subject to scrutiny – politics, religion, and sex.

Academics agree, for example, that criticism of President Mubarak and his family has been completely off limits. "Some people say if anyone talks about the president you will be arrested," said Mai Mustafa, an 'Ain Shams student.85 This area includes discussion of pertinent subjects such as who will succeed the president when he dies or retires and, according to some professors, comments about certain senior officials.86 "There are implicit red lines, for example, the persona of the president, talking about succession, family members of the president," said a political scientist at AUC.87 The red line does not extend to all politics or criticism of the government. "You can talk about the lack of democracy but not the family of the president," Mustapha Kamel al-Sayyid said.88 Egyptians can debate politics, but without using names.

Neither state nor society tolerates criticism, or even innovative interpretations, of Islam. "Religion is all red unless otherwise stated," AUC researcher Reem Saad said.89 The boundaries of what is prohibited are broader and less clear than for politics. "In my case [as a political scientist], there is more room than [there is] for religious issues.... Religious issues are highly sensitive," Cairo University professor Amr Hamzawy said.90 Islamists, who care less about political subjects, apply considerable pressure in the area of religion. Relations between Muslims and Copts (Egyptian Christians) also fall under this restriction. Alexandria University professor Nadia Touba said, "You [might] stay away from issues of Muslims and Christians today. Before it didn't make a difference but today it makes a difference. You don't want to offend anyone. We prefer to avoid [the topic]."91

Public discussion of sex is considered contrary to the religious and cultural traditions of Egypt. At the national universities, professors said they voluntarily stay away from books that challenge the sexual mores of the Muslim world. For example, vivid descriptions of sex or discussions of homosexuality and extramarital sex are off limits. "If something has sex, it's not appropriate for the culture.... [Y]ou have to respect that.... Why would we choose [these books]? We wouldn't feel comfortable teaching them," English professor Dalia El-Shayal said.92 At AUC, censorship of course books has illuminated this red line. The state censor and Islamists have worked together to ban books that deal with sexual topics.

While politics, religion, and sex are the main red lines, other topics are dangerous to discuss in today's universities. According to some academics, criticism of the military is usually off limits.93 Relations with Israel are also a touchy subject for those who challenge the prevailing view. For example, a professor who is willing to speak with Israeli professors is condemned as "supporting normalization," even if he or she opposes the Israeli government's policies.94 "[Discussions of] Israel and the Middle East are biased and unethically presented to the students. It's OK to express your opinion, but they should give students the opportunity to get information and come up with their own opinions," said Margo Abdel Aziz, an education specialist at the U.S. Embassy.95 Public condemnation of such controversial topics quickly leads to self-censorship.

According to one observer, the repression on Egypt's campuses today is a reflection of changes in Egyptian society. "In society in general, the amount of freedom is getting less and less. Academic freedom as one of the signs of freedom in general is bound to be affected," the observer said.96 Violations of academic freedom, however, also exacerbate the problems of society. They threaten to isolate Egypt from the international community and to create an educated class lacking the skills and knowledge to address the country's problems and unable or unwilling to criticize the status quo.

V. Government Repression

State-imposed limits on academic freedom pervade Egyptian universities. Academic life, in Egypt as in all countries, can be divided into four major areas: the classroom, center of teaching and learning; research, professors' work outside of the classroom; student activities, including in sports, arts, service, and politics; and campus demonstrations, where students and professors gather to express their views on political questions or school policies. Using a variety of instruments, the Egyptian government interferes in each of these areas.

Instruments of Repression

The Egyptian government uses three main tools, in various combinations, to stifle academic freedom: a pervasive police presence on campus, the political appointment of key administrators, and a series of laws that regulate internal affairs produce a university system under strict control of the state. "University education in Egypt cannot produce proper intellectuals," said Ahmad Taha, a poet and former professor. "It is nothing more than a government office."97 Using these instruments of repression, the state dictates what material can be taught and studied, restricts what opinions can be expressed and how, and interferes with meetings of professors and students. In so doing, it undermines the autonomy universities need to protect academic freedom and violates basic human rights.

Police Presence

Different branches of the state police, under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior, monitor most aspects of state university life. University guards are stationed at campus gates and have offices in each faculty. Plainclothes members of the state security forces roam campuses to stop spontaneous expression, such as speeches or posters. The police also hire or coerce students into spying on each other. Those belonging to the student club "Horus" are notorious for intimidating their fellow students; this club, or usra, which has branches at the major universities, works for President Mubarak's National Democratic Party (NDP) and receives financial and moral support from the activities department in each faculty.98 Together these forces strive to silence activist students and deter other, less political students from joining them. They suppress specific expression while creating a general climate of fear.

University guards control access to the campus, keeping people both out and in and heavily scrutinizing politically active students in particular. They make it very difficult for visitors to enter the university, and students of various political leanings told Human Rights Watch of being detained or searched at the gates. Iman Kamil, a self-described socialist who graduated in 2000, said the 'Ain Shams guards denied her entry several times even though she presented her university identity card.99 Nadir Muhammad, a

Muslim Brother and third-year student at Cairo University,100 said that guards routinely harass him when he enters campus. If they find he is carrying religious tapes or magazines, they confiscate the material and detain him for a couple hours.101 The university guards also sometimes block exits. To keep student and faculty demonstrations from spilling into more public areas, they close the gates and confine demonstrators to campus. The use of state security forces to monitor university behavior affects private as well as national universities. Guards are stationed at all gates at the American University in Cairo. They check identification cards to screen visitors and close the gates to contain demonstrations.

Members of the state security forces intimidate students with scare tactics. For example, they call students on their cell phones to advise them they are being watched. Alternatively, they call students' parents to tell them they should stop their children from "causing trouble." Family members then apply the pressure the state desires. "It works well, especially among girls. Parents are so frightened, they prevent them from going outside and they stop being involved," said Kamil, whose parents received such a call when she was in school.102 As described in detail below, this is just one of the many means that security forces use to limit student expression on campus. AUC students said they suspect plainclothes police mingle with the crowd on their campus, too. "The security forces penetrate the university," a theater professor said.103 Although it is difficult to prove, this suspicion is a sign of the fear academics feel.

A Cairo University student scales campus gates to hang a banner during a protest on February 22, 2003. State-appointed university guards initially closed the gates in an attempt to contain a leftist demonstration of professors and students.© 2003 Bonnie Docherty / Human Rights Watch

While some faculty members decry the presence of security forces, others see it as a necessary safeguard. For the most part, police leave professors alone,104 but that does not prevent many from resenting government interference in university life. "One of our demands for the last twenty years was to get police off campus," said Cairo University professor Sayyed el-Bahrawy.105 Other faculty members said security forces posed no academic freedom problems and helped keep campuses safe. "I'm happy the security forces are there.... I'm glad they don't let in anybody [to campus]. Otherwise it would turn into a zoo because of the huge numbers of the faculties," said Dalia El-Shayal, an English professor at Cairo University.106 Student protests make some professors ambivalent about the police presence because demonstrators occasionally burn faculty cars and destroy property. A professor from 'Ain Shams said, "The security is intimidating, but what do you do when students get completely out of hand [during demonstrations]? I have mixed feelings."107

Minister of Higher Education Moufid Shehab defended the police presence.108 He noted they take orders from the rector and deans, not from officials outside campus. These administrators, however, represent the state, not autonomous universities. The minister also said that the university guards are "at the university only for order, not to intervene."109 Nonetheless, students and professors repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that the constant presence of security forces on campus and the ways in which they are used by university authorities inhibit freedom at the universities.

Political Appointments

The Egyptian government also controls national universities, the primary source of higher education in Egypt, through politically appointed rectors and deans. The state selects university rectors, or presidents, whose responsibilities include overseeing the "scientific, educational, administrative and financial affairs" of the institutions.110 In 1994, it reversed a twenty-two-year-old policy of letting individual faculties elect their deans and gave the appointment power to rectors.111 Minister of Higher Education Shehab said that the change was necessary because elections had involved dirty campaigns and quarrels between professors. While Egypt is not the only country with appointed deans, professors continue to decry the move.

Faculty members complain that the appointment process gives the state too much control of internal university matters. Mustapha Kamel al-Sayyid, a political scientist at Cairo University, said the deans allow the government to have a dangerous presence on campus.

It's been bad since [the system changed]. All rectors are appointed by the government and are usually NDP [President Mubarak's ruling party] members. Deans are appointed by the rector and therefore have the ambition of becoming rector. They would be unhappy with any action critical of the government. It's an unhealthy atmosphere. We feel deans are the eyes of the government.They don't restrict actions, but it creates a feeling of discomfort. The deans say things pleasing to the government. It reflects badly on an atmosphere of freethinking and debate.112

His colleague Amr Hamzawy described the appointment process as part of the government's move toward increasingly "latent" control, which involves state "integration in the apparatus itself."113 Speaking about the evolution of state repression, Hamzawy said, "There is a different notion of control. Between the sixties and eighties, there was direct control. It eased in the early nineties. Now there is latent control – by regulation, co-opting people, getting critical ability to be controlled by integration in the apparatus itself." He views the appointment of deans, whose job includes "controlling staff members," as part of this systemic restriction of academic freedom.114

The appointed deans wield great power in the academy. They attend lectures, approve guest speakers and research trips, and assign responsibilities to professors.115 They can abuse these powers for political ends. For example, a dean at Cairo University punished Sayyed el-Bahrawy for his leftist political activities by keeping him away from students. The dean refused to let prospective students visit el-Bahrawy in his office in December 2002 and has denied him approval to supervise clubs. "The dean last year told me it is prohibited [for me] to go to demonstrations or speak with students about politics," he said.116 A dean at Dar al-'Ulum, a faculty at Cairo University,117 punished Islamist professors by closing all but one of their offices in 2000. In the aftermath, "[t]here were fifty professors [sharing] one room. The dean believed it was a way to punish Islamists because he said they used their offices to spread Islam," a professor said. Twelve months passed before the administration reopened the offices.118 The system leaves professors no recourse for redress. "If you have a criticism, it wouldn't reach higher [than the dean] because everyone wants to please their boss. We don't have a hand in running the university," said an assistant lecturer in the Faculty of Arts.119

The switch from election to appointment of deans left the disenfranchised professors feeling powerless and cynical. Salah al-Sayyid al-Sirwi of Hilwan University said the system "shows how the state can always control the universities and what happens inside."120 Aida Seif El Dawla, a psychiatry professor at 'Ain Shams, described the policy as an "insult." "They entrusted us with the education of a whole generation taking care of mental health, but not [with choosing] someone who does administrative work."121 An Islamist professor from Dar al-'Ulum described the switch to appointment as the end of the "only free election allowed in Egypt at all."122 He said a professor in his faculty who nominated herself and received only two votes during an election was later appointed dean.123

Although they have no say in the composition of university administration, students as well as professors are affected by the appointment system. "It's very obvious when you compare how deans used to deal with students before and after the law. The conduct of deans is not very good," said 'Issam Hashish, a professor in Cairo's Faculty of Engineering.124 Deans determine who can run for student union and must approve student clubs and public forms of expression. As will be discussed below, they have used this power to interfere with student activities that might challenge the government.

When Human Rights Watch asked Minister of Higher Education Shehab about these concerns, he said that he would consider a system that combines election with nomination. For example, the professors could elect three candidates, from whom the rector would choose one. Or the rector could present a slate of three candidates, on which the professors then vote. A proposed new university law offers an opportunity for a change in policy, but a return to elections is unlikely.125 "Democracy is not always an election.... I personally am against the idea of a pure election," the minister said.126 However deans are selected, they must be free from political pressures and act according to academic rather than political or other criteria. In Egypt today, this is not the case.

Laws and Regulations

The state's third instrument of academic repression is a series of national laws that impinge on campus affairs. The University Law of 1979, which governs the structure of the administration and student activities, exemplifies state interference with the internal workings of the universities via legal means.127 The law, 213 pages in its English translation, gives deans approval power over student union nominees and student clubs. 'Imad Mubarak, recent graduate and lawyer, described this law and the presence of security forces as the two major obstacles to freedom of expression on campus.128 Other laws target freedom of expression in general and, in the process, limit academic freedom. Most notably, Law No. 20/1936 requires that all imported printed material, including course books, be reviewed by the censor's office.129 The academy, like the rest of society, has also felt the effects of Emergency Law, under which Egypt has been governed almost continuously since 1967.130 In February 2003, the government renewed the law, which gives authorities extensive powers to suspend basic liberties, for another three years. It authorizes the arrest of suspects at will and their detention without trial for long periods; the referral of civilians to military or exceptional state security courts whose procedures fall far short of international standards for fair trial; the prohibition of strikes, demonstrations, and public meetings; and the censorship or closing of newspapers in the name of national security.131 This report will discuss the implementation of these laws, and others, in more detail below.

Academic Freedom Violations in the Classroom

In the classroom, the center of academic life, professors and students meet face to face to exchange knowledge and ideas and to discuss them from various perspectives. The Egyptian government interferes with this exchange through a variety of censorship mechanisms. State statutes restrict academic curriculum by legalizing government review of course and library books. Professors at the national universities, who are state employees, censor the opinions of their students during class discussion. Without free access to information and ideas, the learning process becomes routinized, repetitive, and restrictive.

Censorship of Course and Library Books: AUC Case Study

The Egyptian state controls the classroom through censorship of course books. The national universities, which generally rely on a rigid curriculum of textbooks and classics, rarely challenge traditional strictures, but censorship has greatly affected the curriculum at the American University in Cairo. As a purely liberal arts institution, AUC tends to use more diverse and daring books. As an American university, it teaches most of its classes in English and therefore needs to import books from abroad. Both categories of books are vulnerable to the official censorship in Egypt.

Under authority of Law No. 20/1936, the Ministry of Information screens all imported books and periodicals. The statute does not apply exclusively to academic literature, but it facilitates state interference at the heart of the educational system. The two relevant articles state:

Article 9: In order to maintain the public order, it is permissible to prohibit printed matter that is produced abroad from entering into Egypt, and this prohibition can come as a special decision from the Committee of Ministers.

From that follows the need to prohibit the reprinting of this printed matter as well as its publication and distribution inside the country.

Article 10: The Committee of Ministers also has the right to ban the distribution and handling of printed matter of a sexual content as well as that which addresses religions in a way that could destabilize public peace.132

The law thus gives the state power to censor books in the three major red line areas: politics, religion, and sex.

A multistep censorship process screens all books imported by the AUC bookstore, including course books. The store stocks an average of 15,000 titles and 1,000 course books and has a sales volume of 9.4 million Egyptian pounds (LE), or U.S.$1.5 million, each year.133 When the bookstore receives a new shipment of books, it submits an invoice with a list of titles to the censor's office. The office requests to review certain titles, and AUC delivers copies. Because it does not keep good records, the censor's office often asks to review previously approved books, slowing the process and increasing the chances of an overturned decision. After review, the censor tells AUC whether a book is acceptable as is or prohibited. In some cases, a book can be altered to be made acceptable. For example, the bookstore has pasted stickers over illustrations of the Prophet Muhammad, such as one in a book from India, because Islam prohibits images of the prophet. Religious books, which must also be sent to al-Azhar, can take longer to clear. If there are no problems, the process takes a couple weeks.134

Books with titles relating to Egypt or to red line subjects face the greatest risk of censorship. In an order from February 4, 2003, for example, the censor requested to review thirty-eight books, including those with the following titles: Social Life in Egypt, Serpent of the Nile, The Question of Palestine, Shi'ite Islam, Ecstasy, and The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a work of fantasy.135 Bookstore manager Mike Zaug said the censor rarely asks for textbooks but does scrutinize works on politics or classics known for their frank sexuality, like Lolita and Lady Chatterley's Lover.136 Zaug reported that one hundred titles were banned in the first three years after his 1998 arrival at AUC.137 As of February 2003, the most recently banned item was a Penguin Map of the World that showed the Egypt-Sudan border as contested. When Human Rights Watch asked the censor about the map, he replied, "We have a very clear border.... The only maps we go by have a straight line."138