"Bullets Were Falling Like Rain": The Andijan Massacre, May 13, 2005

| Publisher | Human Rights Watch |

| Publication Date | 7 June 2005 |

| Citation / Document Symbol | D1705 |

| Cite as | Human Rights Watch, "Bullets Were Falling Like Rain": The Andijan Massacre, May 13, 2005, 7 June 2005, D1705, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/42c3bd450.html [accessed 1 June 2023] |

| Comments | This report is based on 50 interviews with victims of and witnesses to the May 13 killings. It details the Uzbek government's indiscriminate use of lethal force against unarmed people, describes government efforts to silence witnesses, and places the events against the background of Uzbekistan's worsening human rights record. |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

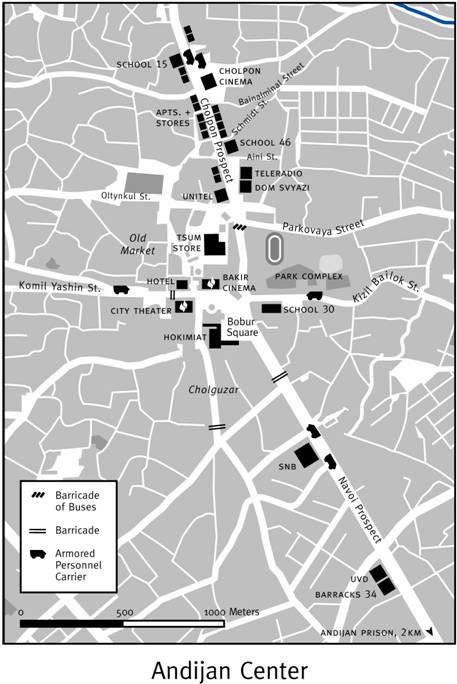

Map of Andijan Center

Most people died near School 15, near the Cholpon Cinema. There were armored cars there, and troops on the road. They were also shooting from the buildings. It was getting dark and the bullets were very big, they would go through several people. The road was completely blocked ahead. We couldn't even raise our heads, the bullets were falling like rain. Whoever raised their head died instantly. I also thought I was going to die right there.– Survivor of the Andijan massacre

The next day [May 14] I heard there were lots of bodies near School No 15, and I went there. I got there before lunch time, but there were already no bodies there – I just saw blood, insides, and brains everywhere on the street. In some places there were up to 1.5 centimeters of dried up blood on the asphalt. There were also lots of shoes – most of them looked really old and shabby, and there were some tiny kids' shoes there. Then I went to the hokimiat and saw the same scene there, plus lots of machine-gun and automatic gun shells.

– A witness to the Andijan massacre

Executive Summary

On May 13, 2005, Uzbek government forces killed hundreds of unarmed people who participated in a massive public protest in the eastern Uzbek city of Andijan. The scale of this killing was so extensive, and its nature was so indiscriminate and disproportionate, that it can best be described as a massacre.

The government has denied all responsibility for the killings. It claims the death toll was 173 people – law enforcement officials and civilians killed by the attackers, along with the attackers themselves. The government says the attackers were "Islamic extremists," who initiated "disturbances" in the city. Uzbek authorities did everything to hide the truth behind the massacre and have tried to block any independent inquiry into the events.

A Human Rights Watch field investigation in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan recreated a comprehensive account of the events of May 13 and 14 in Andijan, presented in this report. Our findings clearly demonstrate the Uzbek government forces' undeniable responsibility for the massacre.

While the government's efforts at sealing off the city and intimidating people from talking about the events to outsiders have made it exceedingly difficult to establish the true death toll – and reveal an attempt to cover up the truth – Human Rights Watch believes that hundreds were killed. Eyewitnesses told us that about 300-400 people were present at the worst shooting incident, which left few survivors. There were several incidents of shooting throughout the day.

The May 13 killings began when thousands of people participated in a rare, massive protest on Bobur Square in Andijan, voicing their anger about growing poverty and government repression. The protest was sparked by the freeing from jail of twenty-three businessmen who were being tried for "religious fundamentalism." These charges were widely perceived as unfair, and had prompted hundreds of people to peacefully protest the trial in the weeks prior to May 13.

The businessmen were freed by a group of armed people who, earlier in the day, raided a military barracks and police station, seized weapons, led a prison break to free the businessmen, took over the local government building, and took law enforcement and government officials hostage.

The attackers who took over government buildings, took people hostage, and used people as human shields, committed serious crimes, punishable under the Uzbek criminal code.1

But neither these crimes nor the peaceful protest that ensued can justify the government's response. It is the right and the duty of any government to stop such crimes as hostage-taking and the takeover of government buildings. However, in doing so, governments are obligated to respect basic human rights standards governing the use of force in police operations. These universal standards are embodied in the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.2 The Basic Principles provide the following:

Law enforcement officials, in carrying out their duty, shall as far as possible apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force.... Whenever the lawful use of force ... is unavoidable, law enforcement officials shall ... exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense.3The legitimate objective should be achieved with minimal damage and injury, and preservation of human life respected.4

As the subsequent sections of this report will show, Uzbek forces did not observe these rules. According to numerous witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, there were many instances on May 13 when government troops on armored personnel carriers and military trucks, as well as snipers, fired indiscriminately into a crowd in which the overwhelming majority of people – numbering in the thousands – were unarmed. While some testimony indicates that, in one shooting incident, security forces first shot into the air, in all other incidents no warnings were given, and no other means of crowd control were attempted.

After troops sealed off the area surrounding the square, they continued to fire from various directions as the protesters attempted to flee. One group of fleeing protesters was literally mowed down by government gunfire. The presence of gunmen in the crowd, and even the possibility that they may have fired at or returned fire from government forces, cannot possibly justify this wanton slaughter.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than fifty people in a refugee camp in neighboring Kyrgyzstan and in Andijan itself who participated in the demonstrations and witnessed the violence, marking the most comprehensive research into the events done so far by any nongovernmental or media organization.

The government sought to justify its acts by casting the events in the context of terrorism, and has claimed that all of the dead were killed by the gunmen, and has stated that the organizers of the protest were Islamic "fanatics and militants" who sought to overthrow the government and establish an Islamic state. This is unsurprising. For nearly a decade, the Uzbek government has cast nearly all of its domestic critics as "terrorists," "extremists," and "Islamic fundamentalists." The government has faced serious incidents of terrorism and insurrection, but it has also used threats of terrorism to justify essentially banning nearly all political opposition, religious or secular. Human Rights Watch research found no evidence that the protesters or the gunmen had an Islamist agenda. Interviews with numerous people present at the demonstrations consistently revealed that the protesters spoke about economic conditions in Andijan, government repression, and unfair trials – and not the creation of an Islamic state.

This report documents the government killings on May 13 and the government attempt to intimidate witnesses in the aftermath. The report places the events of that day against a background of Uzbekistan's worsening human rights record, its brutal campaign against Islamic "fundamentalism," and rising impoverishment, and explains how all three have affected the Fergana Valley in particular.

The Uzbek government has launched a criminal investigation into the events in Andijan, but as of this writing there is no indication that it will include an examination of government forces' use of lethal force against unarmed people.

The Uzbek parliament has created an independent commission of inquiry into the Andijan events whose mandate includes "a thorough analysis of the actions of government and [law enforcement, security and military] structures, and a legal assessment.5" But given evidence to date that the government has sought to cover up its troops' use of indiscriminate force, and the pressure it has put on people not to talk about what happened, it is reasonable to assert that this commission will be subject to political pressure and therefore lack credibility.

Finally, given the government's overall poor human rights record, and in particular its record of impunity for human rights violations, it is unlikely that any government-led investigation would be credible. This makes an independent, international investigation, led by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, imperative for the establishment of a true record of the killings and the start of an accountability process.

The Uzbek government has rejected an international investigation, saying that it is groundless. Last week the foreign minister said the government would allow foreign diplomats to monitor an investigation under way by the Uzbek parliament.6 But given the government's lack of credibility on investigating abuses, this is not enough to guarantee the integrity of the investigation.

While the present report demonstrates the government's use of excessive lethal force, questions about the precise death toll and the units responsible for the killings remain unanswered. A thorough investigation into the killings must therefore include ballistic, forensic and crime scene investigators, and must have unhindered and independent access to hospital, morgue, and other officials records.

We call on the international community, including the United Nations, the European Union, and the governments of the United States, Russian and China, to ensure that such and investigation is launched.

Note on the Use of Names

Most of the names of the witnesses interviewed for this report have been changed to protect their security and the security of their relatives. Government authorities and security forces were continuing to intimidate and arrest witnesses to the killings at the hour of the publication of this report and the safety of witnesses and their relatives could not be guaranteed.

Introduction: Prelude to the May 13 Events

Trial of 23 Businessmen

The Andijan protests were triggered by the arrest and trial of twenty-three successful local businessmen on charges of "religious extremism."7 Arrested in June 2004, they went on trial on February 11, 2005, in the Altinkul district court. Twenty-two defendants faced charges of organizing a criminal group, attempt to overthrow the constitutional order of Uzbekistan, membership in an illegal religious organization and possession or distribution of literature containing a threat to public safety.8 One defendant was charged with abuse of power relating to his professional position.9

According to reports, journalists and most relatives of the defendants were prohibited from observing some sessions of the trial.10 A local activist, Saidjahon Zainabitdinov, served as a non-lawyer public defender for one of the defendants. Zainabitdinov eventually refused to participate in the proceedings, protesting that they were a sham and that the judge refused to allow him to pose questions to witnesses and carry out the defense of his client.11

The government claimed that the men were members of an underground Islamic group, "Akramia" (see below), but the extent to which the defendants subscribed to the teachings of Akram Yuldashev or had links to the Akramia movement is unclear. The father of one of the defendants asserted that all the defendants were simply devout Muslims and successful businessmen who pooled resources to assist the growth of one another's businesses and funded charitable work in the community.12

The defendants' businesses – which included furniture factories, business supply companies, bakeries, tailoring firms, construction companies, and transportation firms – employed thousands of people in impoverished Andijan. The defendants were well known for their role as community leaders. They established a minimum wage that exceeded the meager government-mandated wage, paid employees' medical expenses and sick leave, and provided free meals to staff. They also financially supported a local hospital and orphanage and made donations to local schools and mahalla, or local neighborhood, committees.13

When interviewed by Human Rights Watch in the refugee camp in Kyrgyzstan, the freed businessmen explained that they did indeed have close ties to each other, but that their relationships had nothing to do with religious extremism. Many of their families faced government repression after the 1999 Tashkent bombings (see below), and they were unable to obtain credit from government-controlled banks. The businessmen had joined and used their combined capital to finance each other's businesses.14

Operating outside the government-controlled banking system, the businessmen were beyond the usual levers of state control. In many areas of commerce and industry, they successfully undercut the market share of pro-government monopolies. They enjoyed the loyalty of thousands of employees who were generally paid better and had better working conditions than most others in Andijan. The entrepreneurs' popularity on these grounds presented a challenge to Uzbek authorities.

The twenty-three businessmen were not the only group of entrepreneurs targeted by the government. In January 2005, the authorities arrested a second group of thirteen businessmen on the same charges, and other businessmen in Andijan lived in fear of arrest. One Andijan businessman told Human Rights Watch that he had left Andijan in January for Moscow to escape arrest and that there were rumors that the Andijan authorities had drawn up a list of 500 businessmen whom they suspected of involvement in "Akramia."15

The crackdown on the Andijan business community and the closure of these firms raised tensions not only because of the unfairness of the businessmen's trials. In the already economically depressed Fergana Valley, the loss of thousands of jobs as a direct result of the crackdown was devastating, plunging many families into poverty. And no end to their misery was in sight: instead, the government was continuing to arrest more businessmen and shutting down their companies, adding to the economic hardship.

On April 25, 2005, the defendants announced a hunger strike during the trial to protest the judge's actions at the trial." Defense counsel petitioned the court to have a prosecution witness evaluated for mental fitness to testify, and to call as witnesses Akram Yuldashev as well as the government expert in religious affairs who had issued the conclusion that Yuldashev's writings should be banned as extremist.16

The judge refused all these defense motions, and the defendants abandoned the hunger strike when authorities attempted to force feed them through feeding tubes.17 Throughout the trial, relatives and supporters of the defendants gathered daily outside the court to protest the trial. The demonstrations were orderly and quiet and grew to include several hundred people. On May 10, approximately 700-1000 people protested outside of the city court where the trial was taking place.

On May 11, police arrested three young men who had been supporters of the twenty-three businessmen, apparently on suspicion of beating police officers in a neighborhood in the outskirts of Andijan.18 On May 12, the relatives of the three young men went to the local police station, where one officer acknowledged that the three were also connected to the trial protests. The officer told the relatives that two of the young men were at the local prosecutor's office, and that a third was at the city prosecutor's office, for questioning. No one from the local prosecutor's office would give any information about the two, according to a BBC correspondent who accompanied the relatives to the station.19

May 13: A Day of Violence, Protests, and Massacre

The Attacks in the Night and the Prison Break

The long-simmering tensions and protests over the case of the twenty-three businessmen finally boiled over into open violence on the night of May 12, when the verdict in their trial had been expected. After security officers began to arrest some who had protested the trial,20 a group of friends and family of the businessmen "decided to try to get their friends and family out of detention."21

Around midnight on May 12-13, a group of between fifty to one hundred men first attacked a local police building, and shortly thereafter attacked military barracks no. 34 of the Defense Ministry.22 It is unknown whether the men were armed prior to their attacks on the police building and military barracks, but during these attacks, the men managed to obtain a significant number of weapons, including automatic AK-47 rifles and grenades, as well as a Zil-130 military truck. It appears that the attackers managed to surprise the weakly guarded police and military units, and that only limited fighting took place during both attacks.23 According to the government, the attack resulted in the deaths of four policemen at the police station and two soldiers at the military position.24

The attackers

It appears that most of the attackers were young men, including relatives and supporters of the twenty-three imprisoned businessmen. According to one of the lawyers who defended the twenty-three businessmen, Ravshanbek Khajimov, the attackers were "their friends, their colleagues who were still free, and their relatives who just lost their heads.... They decided that all other means had been exhausted and total injustice was being done, and they could bear it no longer. They decided to resort to force."25 A second witness, a human rights activist from Andijan who went to Bobur Square on the morning of May 13 after hearing some shooting in town, told Human Rights Watch that he saw armed men deployed around the hokimiat (regional government building), after it was firmly under control of the gunmen:

Near the hokimiat, I saw a group of people in civilian clothes armed with submachine guns that kind of guarded the area. I recognized them: they were all familiar faces – people whom I had seen for three months in the court, supporters of the defendants.... I also recognized some people at the door of the hokimiat. I did not dare to go inside the hokimiat.... The gunmen looked like they had been busy fighting throughout the night: their clothes were dirty and shabby.26

The attackers, who referred to each other as "brothers" and may have been members of an informal "brotherhood" of devout Muslims, would remain a cohesive group throughout the unfolding events in Andijan.27 Among their leaders was Sharifjon Shokirov, the brother of one of the twenty-three defendants, Shakir Shokirov. The father of the Shokirov brothers, Bakaram Shokirov, had been imprisoned in 1998 on the charge of religious extremism and was an acquaintance of Akram Yuldashev.28 Sharifjon Shokirov gave statements to the press during the protests, and is believed to have been killed during the government shooting. A second leader, Abduljon Parpiev, who had been imprisoned after the 1999 Tashkent bombings, conducted negotiations with Interior Minister Zokirjon Almatov (see below).29 It is unknown whether Parpiev survived the crackdown.

Although it is clear that a small number of protesters were armed, there is no indication that they were "fanatics and militants" with an Islamist agenda as alleged by President Karimov.30 The president has consistently painted his opponents as Islamic radicals, with little factual basis for such allegations, in a blatant attempt to discredit his opponents and gain international support for his war against "Islamic extremism." None of the demands of the attackers had any manifest relation to Islamic fundamentalism, and Islam was barely mentioned in the speeches in Bobur Square, other than in the form of complaints against the imprisonment of people on charges of "Islamic extremism." Interviews with numerous people present at the demonstrations consistently revealed that the protesters spoke about economic conditions in Andijan, government repression, and unfair trials – and not the creation of an Islamic state. People were shouting Ozodliq! ("Freedom"), not Allahu Akbar! ("God is Great").31

A leaflet found by a reporter on Bobur Square, apparently written in the name of the imprisoned businessmen and distributed to encourage the residents of Andijan to attend the protest march, clearly explains the reasons behind the protest:

We could tolerate it no longer. We are unjustly accused of membership in Akramia. We were tormented for almost a year, but they could not prove us guilty in court. Then they started persecuting our nearest and dearest.If we don't demand our rights, no one else will protect them for us. The problems that affect you trouble us as well. If you have a government job, your salary is not enough to live on. If you earn a living by yourself, they start envying you and putting obstacles in your way. If you talk about your pain, no one will listen. If you demand your rights, they will criminalize you.

Dear Andijanis! Let us defend our rights. Let the region's governor come, and representatives of the President too, and hear our pain. When we make demands together, the authorities should hear us. If we stick together, they will not harm us.32

The prison break

After obtaining weapons, the attackers moved to the Andijan prison after midnight, breaking down the gate of the prison by ramming it with a vehicle. The attackers appear again to have faced minimal resistance and quickly managed to enter the prison. One of the twenty-three defendants, "Faizullo F." (not his real name), explained to Human Rights Watch:

On the twelfth of May, we were ordered to go to sleep at 10:00 p.m. We were woken after midnight. I was on the third floor. After midnight, we heard some noises, shouting and some shooting, single shots. Everything happened very fast. Ten, fifteen minutes later people were inside the prison and started breaking open the doors with metal bars. Those who attacked the prison had weapons, but we didn't. The persons took us out of the cells and said, "Now you are freed from injustice, please go out." At first we were shocked. Then we decided to go down and go out.33

According to the government, three prison guards were killed during the attack. Several of the freed prisoners told Human Rights Watch that they had seen two bodies of guards near the entrance gate, but that they were not sure whether the guards were dead or wounded.

The attackers freed not only the defendants,34 but hundreds of other prisoners, many of them also charged with "religious extremism." The freed prisoners claimed to Human Rights Watch that as many as a thousand prisoners were freed, although the Procuracy General publicly has stated that 527 of the 734 prisoners at the prison were freed during the attack.35 After the attack, the freed prisoners were given the choice of joining a downtown protest, or going home: "The people who attacked the prison said that those who wanted to could go with them to the hokimiat to tell what happened to us."36

Following the attack on the prison, the attackers began to make their way to the hokimiat, and called on others to join them, using cell phones to mobilize known supporters. One of the participants in these early events described to Human Rights Watch how he came to join the events:

My brother-in-law is one of the twenty-three. I was taking part in the demonstrations to protest the unfair trials. Around 1:00 a.m. on the night of the 13th, I got a call and one of the organizers told me to come to the prison. When I arrived there, all of the prisoners were already out on the street. There were about fifty of us [attackers]. We told the prisoners, "if you want to join us, join us, if not, you can go home." Some thirty people came with [our group], the rest went away. We got into two cars and drove to the hokimiat.37

The shooting at the headquarters of the National Security Service

The attackers and the freed prisoners made their way over to the hokimiat, located about six kilometers from the prison. On the way, some of the attackers and their supporters ran into resistance from Uzbek security services being mobilized around the city. One of the participants told Human Rights Watch that soldiers in camouflage ambushed his convoy of two cars on Oshskaia Street, and that three of his colleagues were killed in the ambush.38 However, most of the attackers made it to the hokimiat and easily took over of the building, which had only a single guard during the night.39

A second shooting incident took place as the gunmen moved past the building of the National Security Service (in Russian, Sluzhba Natsionalnoi Bezopasnosti, and known locally as the SNB), which was a focal point of the protester's anger, as SNB officers had arrested and interrogated most of the twenty-three defendants. A heavy gun battle broke out around the SNB building, although it is unclear whether the fighting was initiated by the attackers aiming to overrun the SNB building, or by SNB officers trying to stop the attackers' progress. According to one of the freed defendants who had already reached the hokimiat by the time the shooting at the SNB took place, heavy gunfire at the SNB building lasted for about one hour. A local human rights defender walked by the SNB building, apparently after the attack had been repulsed: "There was blood [on the street] near the SNB building and automatic weapons lying on the street. Under an APC there was the body of a soldier in a bullet-proof vest, and there were bullet marks on the building of the SNB," and a second human rights defender gave an almost identical description to Human Rights Watch.40 According to one of the attackers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, fifteen attackers died at the SNB building, although he personally had only seen two of the bodies.41 A reporter who interviewed Sharifjon Shokirov, one of the protest leaders, also confirmed the attack on the SNB building, writing that SNB officers successfully repelled the attack and that as many as thirty attackers may have died during the assault on the SNB.42

The group of attackers, freed prisoners, and their supporters began reaching the hokimiat long before dawn:

There were only a few people in the square, about one hundred, when we first arrived.... As we reached the square, we just waited. It was still dark, so we were waiting for the morning to come and for the people to join the meeting.43

Meanwhile, the government started pulling its forces up to the city center. A journalist who was making his way to Bobur Square to see what was happening there in the early morning of May 13 told Human Rights Watch:

The first thing I saw was a column of military vehicles, four trucks. These were heavy military trucks, ZIL-131 and URALs. They were followed by a column of ten jeeps, seven or eight were open jeeps, American or British, and the rest were Russian jeeps. Inside were men armed with automatic guns pointed at people. They were going up Navoi Prospect. I saw no policemen in the streets, but near the UVD [local department of Ministry of Interior] we saw huge number of policemen, fully armed and in bullet-proof vests.44

The Protests at Bobur Square

The group began to prepare for a massive protest in Bobur Square, in front of the hokimiat. At the stage next to the Bobur monument at the northern end of the square, a loudspeaker system was activated to allow people to address the growing crowd. While many protesters joined the crowd on their own initiative, the original group continued to use their mobile phones and other means to draw more people to the protest. According to one person who was inside the hokimiat during the protest, the group leader, Sharifjon Shokirov, kept asking his men, "Have you invited the people from the mahallas (neighborhoods)?"45

As the crowd grew into the thousands, the protest was transformed from the actions of several dozen armed gunmen into a massive expression of dissatisfaction with the endemic poverty, corruption, unemployment, repression, and unfair trials that plagued the area. The first speakers were the attackers themselves, who explained to the crowd that they had acted because "they were displeased about the unjust imprisonment of the twenty-three defendants, and demanded justice and a fair sentence in the case."46 They were followed by some of the freed prisoners themselves, who described their unfair trials and the terrible conditions they faced in prison.47

Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch spoke only of gunmen around the hokimiat building and at the perimeter of the square, and not within the protesting crowd or on the speaker podium. Human Rights Watch has reviewed numerous photographs taken by international and local journalists during the protest, and these photographs confirm the description of witnesses of a massive civilian crowd of protesters, as well as the location of a small number of gunmen outside the crowd and away from the protesters. The photographs clearly show that there were large numbers of women and children among the civilians in the square during the protest.

Soon, the loudspeaker was opened to the crowd, and ordinary people came forward to voice their grievances and demand jobs and fair treatment from the government. Even government employees came to the microphone, explaining that they too were suffering, and had not received their salaries since January.48 The crowd soon swelled to thousands persons, according to many accounts, up to 10,000.49 In deeply repressive Uzbekistan, such open expression of discontent was virtually unheard of, and many residents of Andijan quickly took advantage of this unique opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with government policies.

The Taking of Hostages

In the early morning of May 13, as the crowd grew in Bobur Square, the gunmen started taking law enforcement and government officials hostages. Some of the hostages were also captured by unarmed people in the square and handed over to the gunmen.

The first hostages were people in military uniforms, either policemen or military, who drove along the fence surrounding the hokimiat building and started shooting at the crowd through the fence. A witness who at the time was standing near the hokimiat building told Human Rights Watch:

Early in the morning a green car with black windows arrived from the side of Cholguzar with three people inside.50 Two of them came out of the car and fired several shots from sniper rifles at the crowd through the fence around hokimiat. A seven- or ten-year-old boy was killed. The bullet hit him in the head. I saw it with my own eyes. A big group of people rushed there, surrounded and detained these people with their bare hands and took away their weapons. They tied them up, beat them and brought them to the hokimiat. These three people wore very light green or yellowish military uniform, caps and army boots.Fifteen or twenty minutes later people detained a policeman with a submachine gun who was dressed in police uniform but wore a red and blue jacket over the uniform. He made a few shots from his Kalashnikov and also killed a guy.51

One of the gunmen confirmed to Human Rights Watch that they had taken hostages, and explained the process. He claimed that cars of police and soldiers kept driving past the square, shooting at the crowd, and that they started taking hostages in response to these shootings:

We started stopping the cars by throwing stones and blocking the roads. We took the soldiers and policemen out of the cars and took them hostage. Besides, people from the square also brought hostages to us. We kept them inside the hokimiat, there were about twenty of them. We let the soldiers go because we didn't believe them responsible, they were just following orders.... But we kept the policemen, the tax inspector, and the city prosecutor.52

A second man involved in the hostage-taking gave Human Rights Watch a very similar account:

First they came with a military KAMAZ truck and just [drove and] shot at people, and then left. We lost about ten people in that first attack. Also among the crowd were a few police in uniform and some SNB officers.53

The man said that the soldiers first fired shots in the air and that then several small children were hit.

After these first shootings, the people became very angry – Why was the government shooting peaceful people? When they became angry, they started capturing people in uniform, catching seven or eight police officers and five or six SNB officers.Near the hokimiat there were buildings for housing officials, just fifty meters away. The people went to capture these officials also. They captured the prosecutor and the trial judge, and the head of the tax department. About twenty government officials were captured, also some when they came to work. I am a witness to this myself: when they captured the[se] hostages, they did not allow anyone to beat them.54

The hostages were taken into the hokimiat building. Throughout the day, the gunmen as well as civilian protesters continued to bring more hostages into the hokimiat, including suspected government agents in the crowd.

According to several witnesses, more than twenty-five people, and possibly as many as forty persons, were taken hostage.55 Among the hostages were uniformed and plain-clothed policemen, firemen, the head of the tax inspectors, at least one judge, and the city prosecutor. A journalist who was allowed by the gunmen inside the hokimiat told Human Rights Watch that he saw ten tied-up policemen on the second floor of the building.56 In the afternoon, around 3:00 p.m., several of the high-profile hostages were forced to appear in front of the crowd and "confess" their role in the unfair trials of the twenty-three businessmen:

They brought the head of the prosecutor's office and the head of the tax department. They had captured them and brought them to the podium, and told them to tell the truth about the twenty-three jailed persons – they were factory owners and provided work for the people. The [armed] men accused [the prosecutor and tax inspector] of being unjust. The prosecutor said he knew [the defendants] are good [people], but "we can't do anything, we were ordered to do it [convict them], we are like puppets [kukly] in the hands of the power." ... The head of the tax inspectors also said they were compelled to do what the government ordered.57

At the same time, small groups of armed men engaged in skirmishes with government troops in the streets adjacent to Bobur Square, and chaos ruled in parts of the city. The Bakirov and Akhunbabev cinemas were set on fire during the early afternoon, although all of the participants in the events interviewed by Human Rights Watch denied that the militants had been responsible for these arson attacks, instead blaming them on "provocateurs."58 Sporadic fighting also continued in parts of the city away from the square. One witness told Human Rights Watch that his relative, a local policeman, was ambushed with his unit during their morning patrol, in an attack that killed one policeman and forced the others to hide in the bushes. When the police tried to leave, they engaged in a gun battle with six fighters, killing four of them and capturing two.59

The Continuing Rally and Government Shootings

Throughout the day, the protest rally in Bobur Square continued to attract more and more people. The overwhelming majority of people on the square at all times were unarmed protesters, whose numbers grew as the day wore on. By noon the crowd numbered up to 10,000 people, and included many women and children. Two of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch, "Razia R." and "Makhbuba M.," (not their real names) said they had come to the protest with their five and four children respectively.60 According to all of the witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the overwhelming majority of the protesters behaved peacefully and did not engage in any violence or threats. Women and children were sitting on carpets brought to the square from the hokimiat building; at lunchtime, food was distributed.61

Witnesses who were around or inside the hokimiat estimated the number of armed men around and inside the building at between fifty and one hundred; although many people in Bobur Square said they had seen only a few armed men in the area.

However, at various points during the day, troops in armored personnel carriers (APCs) and military trucks periodically drove by, firing randomly into the edge of the largely unarmed crowd. The government had also deployed snipers above the square, but neither the snipers nor the drive-by shooters appeared to be directing fire at persons who were posing any threat. Protesters and observers interviewed by Human Rights Watch all stated that there were almost no armed men on the square itself, and there is no evidence to suggest that the security forces made any attempts to focus their fire on legitimate targets such as the few gunmen in the square. One of the witnesses said, "The people in the APCs were not aiming at specific people, they just shot at the edges of the crowd as they were moving. They were driving and while they drove, they were shooting at people from the side openings of the APCs."62 Means of restoring order or dispersing the crowd short of lethal force do not appear to have been used.

The first attack on the crowd in Bobur Square by security forces took place early in the morning, around 6:00 or 7:00 a.m., when the crowd in the square numbered only about 300 to 400 persons, many of them the released prisoners and the armed men who had attacked the prison. A military vehicle came from the direction of the old market and polyclinic, and opened fire on the crowd from automatic weapons while continuing to drive, ultimately driving away onto Cholpon Prospect.63

Around 10:00 a.m., troops in an APC drove around the edges of the square, firing into the much larger crowd, and killing as many as twelve people, including a young boy and a woman: "They came in one APC and shot [into the crowd] at the edge of the crowd, and then a few minutes later they also came to the opposite edge and shot."64 One of the attackers gave a similar account of the attacks on the protesters:

Several cars drove along the square, and people were shooting from the cars. They were policemen and soldiers. They would kill five, six people in the square as they were shooting, and the rest of the people would get on the ground. The rally would then continue, and people would come back.... Then we started stopping the cars by throwing stones and blocking the roads.... After the cars, an APC arrived. It drove along the square six, seven times, shooting. Every time, several people would fall. It was a yellowish APC. I believe it was military.65

"Muhamed M." (not his real name), a thirty-eight-year-old furniture maker and father of two, recalled how he came to the square and witnessed the attack on the demonstrators at around 10:00 a.m.:

Suddenly, at 10:00 a.m., a military car drove along Komil Yashin Street [running east-west along the edge of the square] and they were just shooting as they were driving. I was shocked they would just shoot at the people. A twelve-year-old boy was shot in the legs right in front of me, a lot of people were wounded.... In front of us, there were no armed people. They were driving at high speed and just shooting as they drove by.66

When asked why he remained in Bobur Square despite this and subsequent attacks, Muhamed M. explained that government repression was directly responsible for the determination of the protesters to stay in the square:

Why did we stay in the square? People had waited for this moment for so long. When we were shot at, we came back. We were waiting for the officials to come to the meeting, we wanted this so badly. The people had become scared because of the repression of the regime, and they had no opportunity to express their problems because of it. People just thought that if they gathered all together and stated their complaints, the government would do nothing [against them]. But if you are alone, one or two, the government would deal with you [arrest you]. That is why the people were so happy the crowd was so big. Finally, after all this time, they could express their problems. The whole population had been waiting for this moment.67

The attacks by APCs firing blindly into the crowds continued throughout the day. One of the witnesses said the snipers deployed around the square were systematically shooting people who had just finished speaking at the podium.68 Because the crowd had grown to fill the entirety of Bobur Square by mid-day and was overflowing into the nearby streets, protesters were often only aware of what was happening in their immediate area, and could no longer see what was happening on opposite sides of the square. But almost all of the protesters recalled regular shooting incidents at the square: "While we were staying in the square, the APC passed through five or six times, driving two ways. The time in between varied, sometimes forty-five minutes or one hour, sometimes longer."69

In addition to those killed from the APC and sniper fire there were many wounded people at the square. The wounded had initially been taken to nearby hospitals, but then security forces began blocking the roads and it became too dangerous to take the wounded to the hospital. A first-aid station was established inside the hokimiat, staffed by doctors and other medical personnel who were attending the protest. It is not known what happened to the wounded in the hokimiat after Bobur Square was stormed (see below).

The Negotiations with the Government

Some of the gunmen made contact with top government officials, and began negotiating with Uzbekistan's interior minister, Zokirjon Almatov. According to a witness who was inside the hokimiat, the contact was initiated when the city prosecutor gave Abduljon Parpiev Almatov's phone number, and urged Parpiev to call Almatov, saying he was certain the government would come to listen to their demands once officials realized how big a crowd had gathered.70 The witness said that Parpiev called Almatov,71 and negotiations began.

This and one other witness familiar with the negotiations, who were interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch, both said that Parpiev demanded that the government respect the human rights of the population, stop illegal arrests and persecutions, and release illegally arrested persons, including Akram Yuldashev. Parpiev also asked Almatov to send a high-ranking government representative to the square to listen to and address the grievances of the population.72 Almatov apparently responded by suggesting that the government open a corridor to Kyrgyzstan to allow the protesters to leave the country – a strategy used in the past to end a stand-off with armed Islamic militants in Central Asia,73 Parpiev tried to explain that this is not what the protesters wanted, saying "Don't look at it like this, you have to come and meet the people and listen to their demands."74 Almatov said he would consider the demands, and call back. According to two separate witnesses, Almatov called back about thirty minutes later and said that the government would not negotiate.75

Aside from the negotiations that took place between the gunmen and the Minister of Interior, there is no indication that the government engaged in any contact with the protesters. All of the witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that no authorities – other than a few local officials who were taken hostage and thus forced to speak – came to address the people, listened to their demands, or requested that they leave the square.

The Storming of Bobur Square and the Killing Zone

For most of the day, the protesters in the square endured periodic attacks by the security forces. According to witnesses who were at different locations in the square at the time of these attacks, each of the attacks resulted in casualties among the protesters. One of the witnesses said that he saw five people wounded around him.76 Another witness, who was standing near the Bobur monument, recalled:

An APC was moving by, shooting at the street and at the square. Three people who were standing not far from me were killed. One of them was hit with a bullet in the head – the entire upper part of his scull was blown off by the shot. The other one was hit by two bullets – one in the stomach and one in the neck. I could not tell how the third one was wounded – other people carried him away immediately. When the APC drove by I suddenly felt like my right ear was burning – I thought I was wounded, but it turned out the bullet passed just by me. I became deaf for some time.77

Human Rights Watch does not know of any source that performed a body count, but through the interviews we have conducted, it seems likely that well more than a dozen, and possibly up to fifty persons were killed in these early skirmishes.

Rumors spread around the square that President Karimov himself was coming to address the crowd, as demanded by the protesters. The demands of the protesters in Andijan had belied the government's own claims that they were "fanatic and extremist groups" aiming to "overthrow the constitutional government." Witness after witness told Human Rights Watch that the main aim of the protest was to bring their grievances to the attention of President Karimov, and that cheers had gone up in the crowd when it was incorrectly announced that Karimov was coming. A baker with two children arrived at the protest in the afternoon and stayed on, even after being shot at:

After the shooting was done, the people just stood up and continued with the meeting. People were waiting for the president to come. They wanted to meet him and explain their problems. They wanted to know if their problems came from the local [administrative] level, or if they came from the top. We wanted to ask the president to solve our problems and make our lives easier, but we were not trying to get rid of the government of Karimov.78

Another woman said, "I came to the protest with my five kids. We came there because the president had always promised to take care of the people and we believed [him]; we heard [rumors] and we were hoping that the president would come and we were waiting for him."79

A third witness, a mother of two, simply said, "we stayed in the square because we thought Karimov was coming, especially when we saw the helicopter flying overhead.... We were expecting Karimov, but they started shooting at us instead."80

Sealing off of Bobur Square

Despite the expectations of the demonstrators, no government official came to address the crowd. Instead, the security forces began to prepare to attack the protesters. Protesters had still been able to freely reach the square at 3:00 p.m.,81 but by about 4:00 p.m., they began to understand that the roads around the square were being blocked off:

People said that we were all blocked off, that the military had deployed in all the streets, that there was no way out of there and that the troops were going to storm the square. We did not see the troops, but the people who tried to get out told us about this. The military did not let people in or out. People who tried to escape through the side streets near the Detskii Mir shop [one block north of the square, along Cholpon Prospect] returned and said the road was blocked.... The people were getting panicked.82

Most of the roads out of Bobur Square were blocked by government troops, APCs, or by buses parked across the road. Navoi Prospect and Cholguzar streets, running south from the square, were both blocked; troops were also deployed at School 30, the park east of the square, and at the market area north of the square. The only effective escape path was north onto the main avenue of the city, Cholpon Prospect, which had also been blocked off by three buses being parked across the road.

Shortly after 5:00 p.m., APCs and military lorries suddenly arrived at the far end of the square, and the troops began firing directly into the massive crowd. Other troops emerged from behind the hokimiat, which by this time had brick barricades around it, and various side streets. Galima Bukharbaeva, the Uzbekistan project director for the impartial Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR), was in the square at the time of the assault and later described it in her dispatch:

The assault began at 5:20 p.m. local time. At least nine people were killed in the first volley of gunfire. Their fellow demonstrators carried their blood-covered bodies inside the compound of the Andijan regional government building, which was being held by protesters....The eight-wheeled armoured personnel carriers, APCs, appeared out of nowhere, moving through the streets at speed, past the people on the outer fringes of the rally. The first column of vehicles thundered past without taking any aggressive action.

But a second column arriving five minutes later suddenly opened fire on the crowds, firing off round after round without even slowing down to take aim ... . Overhead, helicopters circled, clearly spying out where the biggest concentrations of people were gathered.83

Another journalist, who was standing near the hokimiat at the time, provided a similar account to Human Rights Watch:

At 5:15 p.m. I saw an APC and then a truck moving along Navoi Prospect. They passed by me and moved up towards Cholpon Prospect... Five minutes later I saw another truck on Navoi Prospect. While the first truck was covered with an awning and there were submachine-gunners inside, the second one had an open top and there were thirty or forty soldiers with Kalashnikovs sitting there. There wore camouflage uniforms. Those were military uniforms and a military truck.I felt that something is about to happen and moved to a more secure location, closer to the pavement. The truck stopped at a distance of five or six meters from me. And as soon as it stopped, they opened fire, without any warning.I immediately hit the ground. It lasted for may be a minute, was hard to tell. The truck was moving all the time and shooting in all directions... I could not see what was happening on the square. When the shooting ceased, I got up and started running... People were fleeing from the square, the [sounds of] heavy shooting were coming from there, and two columns of smoke were rising into the air.84

Numerous witnesses told Human Rights Watch that the attack on the square, like the previous attacks throughout the day, took place without any warning. Those interviewed said that the authorities did not make any announcements to order the massive crowd to disperse or to warn them of the upcoming attack, or to call on the gunmen to surrender. Certainly the Uzbek authorities could have issued warning calls, using the public address systems of the APCs or the helicopters flying overhead, or from the neighboring apartment buildings in which snipers were deployed. One of the demonstrators recalled: "No one from the government gave any warning. We were just waiting for a government representative [to come talk to us]. There were no announcements to leave the square, and without any warning they just started to shoot."85 A second witness told Human Rights Watch: "There was no warning, they started shooting without any warning."86

The shooting [at the square] was very severe, and a lot of people died there. After this, the people were directed to go to the side of the old city," recalled one survivor. Panic ensued in the crowd. A woman who had been in the crowd told Human Rights Watch: "There was a guy on the podium, and he was shouting, 'Look! Look, people! At the back they are shooting at us! People are dying! Run away!"87

A journalist who was trying to escape along with a group of about a dozen people said that around 5:45 p.m. he heard heavy shooting right behind him. He said:

I turned around and saw an armored personnel carrier moving right on to us... We started running in the direction of the square, and we got very lucky – there was a park on our way, the side gates were open, and we ran in. I was counting from there – after the APCs, five URAL trucks passed by. As we were running through the park, we kept hearing heavy submachine gun fire. They were shooting at us, at all the people who were fleeing... We understood that a real carnage was happening there.88

Human shields and the flight down Cholpon Prospect

Another survivor gave a detailed account of the chaos which ensued when government troops stormed the square, and of the failed effort by the armed militants to bring the massive crowd to safety by using the hostages as human shields:

Then the shooting started. We saw people falling down from the shooting, I saw a twelve-year-old boy killed next to me. People got up confused, saying "They are shooting us, people are dying!" After standing up, we ran to all sides. People were being shot as we ran, and fell down. The fellows who brought the prosecutors and tax inspector [to the podium] brought the people together. They told us not to be afraid – they would put the hostages in front of the crowd to cover us. They told us [over the microphone] that when the soldiers saw the government people, they would not shoot us. We were directed towards Cholpon Prospect. I can't say how big our group was, we were running and pushing our way out of the square. If you ran into another direction, you were shot, so your life depended on staying with the group.89

Two separate groups made their way into Cholpon Prospect: a first group of about three hundred persons, mostly men, with a large group of hostages in front of them, and a second, much larger group, which included many women, children and old men, and was surrounded by men trying to protect them and also headed by a group of hostages.90 "At 6:00 p.m., the shooting started again, "Kamil K." (not his real name), who was in the second group, told Human Rights Watch the following:

People were afraid they were being attacked. Two hundred or three hundred people took fifteen or twenty of the hostages in front of them, and headed towards Cholpon Prospect.... There were about 500 meters between us and this first group, and we also had hostages in front of us, maybe six or so policemen.91

As the crowd moved into Cholpon Prospect and headed north, they immediately found their way blocked by three buses parked across it, at the crossing of Parkovaya Street. Some shots were fired at parts of the crowd from the area of the stadium to the right.92 The panicked crowd pushed aside the middle bus to allow people to pass through, but soon came under heavier fire as people moved ahead. "The shooting began again as we passed the buses. Automatic weapons were being fired at us from everywhere, from the roofs and behind the trees," one survivor recalled.93 A second witness told Human Rights Watch:

I saw a few buses in front of us that blocked the road. People pushed one of them aside and made their way through. The shooting resumed. I heard a scream behind me. I looked back and saw a man with half of his head. The shooting became heavier. The number of wounded was more than those killed. They fired at us with all kinds of weapons. There were [red] tracer bullets. People got down on the ground and the shooting stopped. Then we got up and walked again. After we walked twenty meters the shooting resumed.94

The killing near School 15

The worst was still to come. Just a hundred meters ahead, APCs were parked across the road, effectively blocking the main escape route of the crowd, and trapping the crowd in a sniper alley. In front of the APCs, soldiers were laying down on the ground behind sandbags. As the first group reached this area, they were wiped out by the fire from the APCs, the soldiers behind sandbags, and soldiers shooting from the roofs of nearby apartments. The second group similarly came under heavy fire, causing massive casualties. "As we moved ahead on Cholpon Prospect, we saw the APCs and the soldiers lying down in front of them," one survivor from the second group stated. "We were just shocked. It was like a bowling game, when the ball strikes the pins and everything falls down. There were flashes from the APCs, there were bodies everywhere. I don't think anyone in front of us survived," he said.95 Another survivor recalled:

At School 15, in front of us were several armored cars at a distance of about 300 meters. They started shooting and people were screaming. We lay down, and some tried to run away. They were also shooting from the roofs of Cholpon Cinema. There were also soldiers on the ground [in front of the APCs] shooting at us. The street was full of blood.96

All of the other witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been present in Cholpon Prospect gave almost identical testimony of the heavy fire they faced when they came face to face with the APCs blocking Cholpon Prospect near School 15. "Yuldash Yu.", a businessman freed during the prison break, told Human Rights Watch:

Most people died near School 15, near the Cholpon Cinema. There were armored cars there, and troops on the road. They were also shooting from the buildings. It was getting dark ... The road was completely blocked ahead. We couldn't even raise our heads, the bullets were falling like rain. Whoever raised their head died instantly. I also thought I was going to die right there.97

Almost all of the people in the first group to move up Cholpon Prospect were killed near School 15, and heavy casualties resulted in the second group as well. "When we came to Cholpon Cinema, we saw how the first group of [200 to 300] people had been shot dead," recalled one survivor of the second group.98

As the fleeing people were trapped at the top of Cholpon Prospect, thousands of protesters were attempting to leave the square but became effectively trapped in a sniper alley behind the lead group, unable to flee to safety. As they attempted to move down Cholpon Prospect and were blocked from advancing, they came under constant fire from snipers located in the apartment buildings and a school lining the roads, as well as soldiers located in the trees along the road: "As we moved past the buses, we continued to head down Cholpon Prospect. Along the way, there were four and five-story buildings. They were shooting from those buildings' apartments, and about 100 people died here," one survivor recalled.99 A second survivor said:

Some soldiers had climbed into the trees and the buildings and they were shooting down on us. I was in the middle of the crowd, a distance from the front. I had not yet gone past Cholpon Cinema. One man was killed right in front of me, he was shot in the head and we were covered with his blood. People went to lie down, but this did not stop the shooting.There were two buses right near the square, at the beginning of Cholpon Prospect [blocking the road]. They did not block the street completely, we had some space [to sneak through]. They were shooting all around us, all around, even in the park. The whole Cholpon Prospect was a shooting gallery, they were shooting from the roofs of the apartments. They shot at people when they tried to move. I raised my head, and as soon as I did, they fired [on me]. Nobody could help anyone, because if you tried to move they would shoot at you.100

Two of those interviewed told Human Rights Watch that the gunmen who were moving along with the crowd fired back at the government troops. One witness said:

When I walked with the crowd along the Cholpon Prospect I saw several armed men among us who fired at the soldiers. People shouted at them, 'Do not shoot! Do not shoot!,' but they did. They were in civilian clothes and walked aside from the crowd, hiding themselves closer to the houses.101

Another witness, "Shukkhrat Sh." (not his real name) said, "First we sent the women and then we followed [onto Bainalminal street]. Two or three people with weapons stayed behind [on the corner], to cover the others, but they [gunmen] were killed."102

The presence of gunmen in the crowd, and the fact that some of them fired at or returned fire from government forces, cannot possibly justify this wanton slaughter.

The heavy fire from the APCs and the snipers killed hundreds of protesters, as well as all but four of the hostages. One of the survivors recalled suddenly finding himself in front of the crowd as row after row of people was mowed down, and seeing a street of dead bodies ahead of him: "Ahead of us, I saw the road blocked by APCs, and there were 150 to 250 people dead in the street.... The man right in front of me was shot and died."103

Realizing that there was no escape on the main road, the survivors decided to veer right, onto the small Bainalminal Street, still facing heavy gunfire. As people around them were being shot down, the survivors ran for their lives. "Our women were the first to turn onto Bainalminal Street. There was a low fence at the sidewalk, and some of us jumped over the fence, but the people who followed broke it down. Many people of our group were killed there," one person recalled.104 They left behind a street filled with bodies and wounded people.

The Flight from Andijan

A group of more than six hundred survivors made their way out of Cholpon Prospect, and remained together, deciding to flee to Kyrgyzstan. Much of the information in this report is based on the information of this single column of refugees, who fled Bobur Square together in one direction and entered what can only be described as the "killing zone" of Cholpon Prospect. It is not known what happened to the protesters who fled in other directions from the square, and it is possible that other significant casualties were caused by troops firing on those fleeing protesters, as well. The survivors of Cholpon Prospect made their way to Kyrgyzstan and lived to tell their stories. As Andijan remains sealed off at the time of the writing of this report, little is known about the fate of protesters who fled in other directions.

The fleeing survivors left with local residents, many of the wounded and others unable to make the fifty kilometer walk to the Kyrgyz border: "We had a lot of old and wounded people with us who couldn't walk, so we left them at the gates of the houses, with the local people."105 It is not known what became of these wounded persons.

The Cholpon Prospect survivors walked throughout the night towards the border with Kyrgyzstan, remaining in a tight-knit group. One of the women with the group recalled the exhausting, desperate journey:

I was wearing high heeled shoes, and had to take them off and continue barefoot. It started raining and we were all wet. We walked on a gravel road, and we had to keep going. If you slowed down, the people behind you would just push you. We couldn't use the toilet or drink water. We knocked on some doors, but the people just told us to go away, they were very afraid. It took eleven, twelve hours to walk to the border.106

When the group reached the border town of Teshik-Tosh around 6:00 a.m., they did not know how to cross. Local villagers offered to show them the way. As they crossed a small hill, they came under fire from Uzbek soldiers or border troops, and two local villagers showing them the way were killed:

When we reached Teshik-Tosh, a villager said there was another way to Kyrgyzstan through the hills. We had to reach Kyrgyzstan by any means. He showed the road and we followed him.... I was in the rear, in the front were mostly women. Troops were waiting for us up ahead, they were expecting us. We got ambushed, they opened fire on us. I myself saw three dead women, three dead men, and a dead child. A lot of people were wounded in the back, they were shot as they were running away.107

Local residents in the Pakhtabad border area of Uzbekistan said that Uzbek authorities had warned them not to open their doors and that a large crowd of armed people were moving towards the area.108 The crowd retreated to the village of Teshik-Tosh, where a nurse in the crowd attempted to save the wounded. In total, eight people were killed in the ambush, including thirty-six-year-old Odinakhan Teshebaeva, a mother of two, forty-three-year-old Hidaiat Zahidova, twenty-two-year-old Makhbuba Egamberdieva, and a boy aged around nineteen.109 Between eight and twelve people were wounded. The local villagers managed to arrange for ambulances to take away the wounded, but some of the wounded refused to go with the ambulances, afraid they would be arrested or killed if they remained in Uzbekistan.

Human Rights Watch investigated media reports that further unrest in Pakhtabad had resulted in the deaths of some two hundred persons. A visit to the town of Pakhtabad found no evidence of unrest there. It appears that the only incident in the area took place in the village of Teshik-Tosh, as described above, which is near the Pakhtabad administrative district.

Ultimately, after negotiating for safe passage into Kyrgyzstan, the group managed to cross safely to Kyrgyzstan, where they remain to date.

Lack of Medical Attention for the Wounded, and the Execution of Wounded Persons

Human Rights Watch was able to locate two survivors who were wounded but remained in Cholpon Prospect until the next morning, May 14. Both gave troubling accounts suggesting that throughout the night no ambulances were brought to evacuate the wounded and, on the contrary, that people were simply left to die in the street. According to both witnesses, soldiers began to summarily execute the wounded during the morning of May 14.

"Rustam R." was in the first group of people to arrive at the killing zone near School 15, and was shot in the arm but managed to crawl and hide in a nearby construction college. He told Human Rights Watch:

When the shooting started, the first rows fell. I lay on the ground for two hours, fearing to move. From time to time, the soldiers continued to shoot when someone raised their head. When it got dark, I was wounded in my arm and started crawling away. I got to the construction college and hid there for the night [and was unconscious much of the time].Around 5:00 a.m., five KAMAZ trucks arrived and a bus with soldiers. The soldiers would ask the wounded, "Where are the rest of you?" When they would not respond, they would shoot them dead and load them into the trucks. There were no ambulances there.... Soldiers were cleaning the [area of] bodies for two hours, but they left about fifteen bodies on the spot.110

A second witness, one of the hostages who was in front of the first group, survived by remaining motionless under several dead bodies throughout the night. His testimony also shows that no ambulances came to collect the wounded throughout the night, and that soldiers continued to kill wounded persons:

[The shooting] lasted [sporadically] almost until the morning.... There were four dead bodies on top of me. When someone tried to get up, the shooting would start again. Close to morning, someone walked up to me, [touched me] and said in Russian, "Oh fuck, there are still people alive here!" He touched my leg and said, "He is still warm!" Apparently, he wanted to kill me ... Around 6:00 a.m., everything became very quiet. APCs started moving back and forth. Four of us were wounded [but survived]: a Ministry of Emergency guy, a fireman, a policeman, and myself. All of us were seriously wounded. I believe there were only four of us alive in the area. Prosecutors arrived and were making video footage. They ordered us to lay there until our identities could be checked. The prosecutor and a policeman recognized me and they took us on a bus. As we were getting on the bus, I turned around and saw the bodies. There were many of them, on the road and the sides of the road.111

A human rights activist from Andijan confirmed to Human Rights Watch that seventeen bodies remained in the street when he went to the area on the morning of May 14, and that all were muscular males. He believed the bodies had been left to create the impression that only militant-looking men had been killed, and to lower the official body-count of the incident.112

Another group of bodies was seen by witnesses near the hokimiat building on May 14. The bodies matched a similar profile. "Tursinbai T." said:

I saw thirteen bodies not far from the hokimiat, near the Bobur statue. I was looking for my friends among them, but have not found anyone. All of these bodies were big men thirty to fifty years old. Their feet and jaws were already tied in accordance with Muslim tradition. Many people came there to look for their relatives among these bodies but I have not seen anyone taking any of the bodies from there.113

Later in the morning of May 14, Andijan residents who went out into the streets looking for their relatives and friends were able to observe unmistakable evidence of the night's bloodshed. "Tursunbai T." was one of them. He told Human Rights Watch:

The next day [May 14] I heard there were lots of bodies near School No. 15, and I went there. I got there before lunch time, but there were already no bodies there – I just saw blood, insides and brains everywhere on the street. In some places there were up to 1.5 centimeters of dried up blood on the asphalt. There were also lots of shoes – most of them looked really old and shabby, and there were some tiny kids' shoes there. Then I went to the hokimiat and saw the same scene there, plus lots of machine-gun and automatic gun shells.114

The Aftermath of the May 13 Shootings

The Government's Account of the Events

The government has characterized the Andijan events as an attempt by terrorists, motivated by an Islamist agenda and supported by foreigners, to seize power in Andijan.115 It has attributed all deaths to the gunmen and in public has not explicitly acknowledged any casualties inflicted by government forces.

The government rejects characterizing the gathering on Bobur Square as a "protest." In his statement to the press on May 19, President Karimov said that after gunmen seized the weapons, the army barracks no. 34, and conducted the prison break, they gathered people at the hokimiat "and used them as human shields."116 President Karimov also said that people were promised up to U.S. $3,000 to go Bobur Square.117

President Karimov said that he personally went to Andijan to set up headquarters, consulted with local leaders, and sought to establish contact with the gunmen. Minister of Internal Affairs, Zokirjon Almatov, then was tasked with negotiating with the gunmen.118 As Karimov said at the press conference, the negotiations continued for the whole day until 5:00 p.m. when the gunmen rejected the last government proposal that would allow them to leave the city. They left the hokimiat building after they realized that the military were surrounding them, he said. President Karimov said that after the gunmen left the hokimiat building, at about 7:40 p.m., government forces "pursued" them, and indicated that government forces fired only in response to gunfire from the gunmen.119

The government denies that military or internal affairs troops shot at fleeing protesters, and has attributed all deaths to the gunmen. Minister Almatov told diplomats and journalists visiting Andijan on May 18 that "the extremeists ... forced their way through the ring of law enforcement bodies using women and children douched [sic] with gasoline as a cover. The terrorists shot down dozens of peaceful people, including three ambulance doctors going by."120

The government has launched an investigation into "terrorism, attacking the constitutional order, murder, the organization of a criminal band, mass disturbances, the taking of hostages, and illegal possession of arms and explosive materials."121 According to Xinhua news agency, the prosecutor's office announced the arrest of fifty-two of ninety-eight people detained for the Andijan "riot."122 To date, no government statement of which Human Rights Watch is aware has indicated that the criminal investigation will examine the government's use of lethal force.

The Uzbek parliament has created an independent commission of inquiry into the Andijan events whose mandate includes "a thorough analysis of the actions of government and [law enforcement, security and military] structures, and a legal assessment.123"

President Karimov has categorically rejected an international investigation, suggesting that it would be inconsistent with Uzbekistan's sovereignty, that it would cause further upheaval, and would be biased.124

Unknown Fate of the Bodies

One of the enduring mysteries of the Andijan events is the fate of the bodies of those killed. After the authorities removed most of the bodies from the streets during the night of May 13, they delivered some of them to at least one official and several ad-hoc morgues. Some of the bodies were buried by the authorities in the following days rather than being handed over to the families for burial, probably because the morgues did not have the storage capacity for all of the bodies.

While some families managed to find the bodies of their relatives in the streets immediately after the killings or later in the local morgue, as of this writing it is unclear where most of the bodies were taken. Human Rights Watch was unable to verify persistent rumors about mass graves in various locations outside of the city, yet a large number of the bodies clearly did not end up in the local morgue. A law enforcement official who was among the team collecting the bodies told his relative that:

I was called in on May 14 and we were loading the bodies – from the square and the avenue [Cholpon Prospect]. I think there were about 500 bodies there. We first brought them in three URAL trucks to the morgue, but there was no space there, and the trucks had to leave. I was not with the group that drove [the bodies] away from the morgue, but colleagues said they were taken to Bogshamal [an area outside Andijan where there is a cemetery].125

Several other witnesses also mentioned a rumor that some bodies were buried near the Bogshamal cemetery.126 This and other suspected burial places were off limits for journalists and human rights workers. A journalist who tried to investigate the Andijan slaughter cited a Bogshamal cemetery caretaker saying that thirty-seven bodies had been buried by government workers in a nearby field. The journalist, who reportedly visited sixteen cemeteries in Andijan, said he had found only sixty-one graves of the people allegedly killed in the city during the May 13 events.127

It is unclear whether any investigative activity preceded the removal of the bodies from Cholpon Prospect on May 14 and whether the necessary forensic and ballistic examinations, such as on-the-spot photographing, identification, or collecting of material evidence (clothes, bullet shells, etc.) have been undertaken. Aside from one person who mentioned that law enforcement officials were shooting video footage on Cholpon Prospect in the early morning, none of the three other witnesses whom Human Rights Watch interviewed who saw the crime scene the next day observed any of these measures taken. The fact that some of the bodies of militant-looking men were left in Cholpon Prospect and near the hokimiat building (see above) suggests that the government might have already started arranging the evidence at that point to corroborate its version of the events.

It does appear that a number of the bodies were photographed at some point to help with identification, as some relatives looking for the missing were given stacks of photographs of individual corpses to look through.128 It is unclear, however, whether the authorities took steps such as compiling full lists of those killed, notifying relatives, or keeping track of identification documents found on corpses, all measures to facilitate people's efforts to locate and identify dead relatives.

The way the bodies were removed from the streets and handled made it very difficult for families to find the bodies of their relatives and bury them. The family of twenty-five-year-old "Khassan Kh." (not his real name), who was killed while trying to return home from the Old Market, where he worked, found his body in the morgue after several days of searching. His relative said:

We were looking for him everywhere around the city, and then we went to the morgue on Semashko street. Lots of bodies were piled up there, with their insides out. There were so many bodies there – we kept looking for a long time. We hardly found him – there was almost nothing left from his head, we recognized him by his clothes. There were soldiers and policemen in the morgue. They asked, 'who was your son?' We told them he was just a tradesman in the market and then they told [the morgue workers] to give the body to us.129

Almost two weeks after the events, some families were still looking for their relatives. "Orzibeka O." (not her real name) told Human Rights Watch that she has not seen her fifteen-year old son since 5:30 p.m. on May 13 when he left with his friends to see what was happening in the city. She was waiting for him all night and went to look for him at dawn the next day. She said:

First I went to Sai [area]. Other people also came there to look for their relatives. I heard that about forty dead bodies were there. But I did not find him there. I also checked in all hospitals and morgues, but he was not there. When I looked through the lists in the morgue, I saw 390 names but I did not see my son's name among them.130

The woman eventually came to Kyrgyzstan hoping that her son might have been among the refugees who fled across the border after the May 13 events. However, she did not find him in the camp.