"Keep Your Head Down": Unprotected Migrants in South Africa

| Publisher | Human Rights Watch |

| Publication Date | 28 February 2007 |

| Citation / Document Symbol | volume 19, no. 3(a) |

| Reference | volume 19, no. 3(a) |

| Cite as | Human Rights Watch, "Keep Your Head Down": Unprotected Migrants in South Africa, 28 February 2007, volume 19, no. 3(a), available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/45eecad12.html [accessed 5 June 2023] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Glossary

| ACHPR | African (Banjul) Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights |

| BCE | Basic Conditions of Employment |

| ICERD | International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination |

| DHA | Department of Home Affairs |

| DoL | Department of Labour |

| ETD | Emergency Travel Document |

| ICCPR | International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

| ICESCR | International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights |

| IOM | International Organization for Migration |

| MOU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| SADC | Southern African Development Community |

| SAHRC | South African Human Rights Commission |

| TAU | Transvaal Agricultural Union |

| R | South African rand |

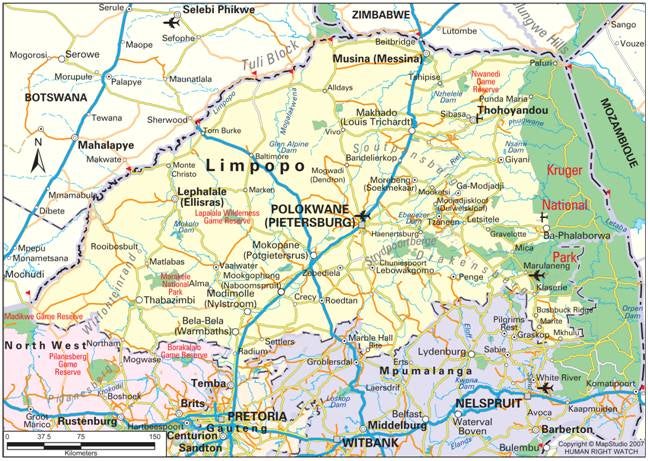

Map of Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces

© 2007 Map Studio

Map of Limpopo Province

© 2007 Map Studio

Map of Mpumalanga Province

© 2007 Map Studio

Summary

South Africa's vibrant and diverse economy is a powerful draw for Africans from other countries migrating in search of work. But the chance of earning a wage can come with a price: If undocumented, foreign migrants are liable to be arrested, detained, and deported in circumstances and under conditions that flout South Africa's own laws. And as highlighted by the situation in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces, both documented and undocumented foreign farm workers may have their rights under South Africa's basic employment law protections violated by employers in ways ranging from wage exploitation to uncompensated workplace injury, and from appalling housing conditions to workplace violence.

Human Rights Watch has conducted research on the situation and experiences of migrant workers around the globe. Its research demonstrates that migrant workers, whether documented or undocumented, are particularly vulnerable to human rights abuses. Such abuses can be the result of many different factors including inadequate legal protections, illegal actions of unscrupulous employers or state officials, and lack of state capacity or political will to enforce legal protections and to hold abusive employers and officials to account. The focus of this report is principally the situation of Zimbabweans and Mozambicans in South Africa's Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces.

Human Rights Watch believes that in South Africa migrants are regularly subject to human rights violations when they are deported, and that South Africa's Immigration Act 2002 is routinely violated. Human Rights Watch researchers spoke with several witnesses who reported that when apprehending suspected undocumented foreigners, police, immigration, and military personnel had assaulted them and extorted money. In one case, a border military patrol failed to prevent the rape of an undocumented migrant whom they had arrested. Unaccompanied child migrants detained by South African officials are held in police cells with adults, contrary to both domestic and international standards relating to the detention of minors. Deportees allege that police on deportation trains sometimes assault and extort money from them, and have even thrown deportees – who believe they have bought their freedom – off moving trains to their death. Immigration policy provides that foreign migrants facing deportation should be allowed to collect their unpaid wages, savings, and personal possessions, but in practice this seldom occurs.

On the farms of Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces, many farmers who produce on a large-scale for export or for the domestic market use only documented workers. This leaves farm owners whose market contributions and labor forces are much smaller as the principal employers of undocumented workers. But documented or not, workers experience abuse and exploitation: While many large-scale farmers do adhere to the basic conditions of employment law, other farmers openly disregard the minimum wage, do not pay overtime, sick leave, or annual leave, and make unlawful deductions from workers' wages. Existing legislation also creates disincentives for employers to provide housing for workers. Farm workers are still too often the victims of violence by employers and other farm staff, which the workers may be unwilling to report for fear of losing their jobs.

Many employers do not claim state compensation to be passed on to farm workers who are injured at work, and when they do, the practice whereby payments can only be made into a bank account creates a barrier for foreign workers (who normally are unable to have accounts) to receive compensation settlements.

Although the aspect of the report covering abuse in employment focuses on the human rights situation of foreign migrant workers on farms in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces, it also provides one of the first assessments of employment conditions on farms since the introduction of a minimum wage in 2003. Its findings also suggest that South African farm workers suffer a similar lack of legal protection as foreign farm workers regarding basic employment conditions.

Failures by the government to ensure respect for international human rights law and South African immigration and employment laws, as well as certain deficiencies in those South African laws, result in the infringement of rights that migrants, documented and undocumented, should enjoy under international law and that are also protected by the Constitution of South Africa. These rights include, among others, the right to personal freedom, liberty and security, to appropriate conditions of detention, and to fair conditions or practices of work. The South African government should ensure that state officials abide by the procedures for arrest, detention, and deportation in its immigration law. The government should also create a system that permits migrants to report abuses of their human rights; require labor inspectors to produce public reports documenting the number of inspections they conduct, complaints they investigate, and compliance orders they issue to employers for violations of employment law; and investigate and punish state officials and employers who violate the law. The government should remove obstacles to enable migrant workers to access the workers' compensation to which they are legally entitled. Human Rights Watch calls on the government of South Africa to offset practical disincentives for farmers to provide housing by developing a housing policy for farm workers.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the government of South Africa to amend its immigration law to include enforceable rights for undocumented migrants to obtain their wages and possessions in the event that they are deported. The government is urged to become a party to the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families and to incorporate its provisions in domestic law.

The report is based on research on Zimbabweans in Limpopo province in late April and early May 2006, and in Beitbridge, Zimbabwe, in October 2006, and research on Mozambicans in Mpumalanga and Limpopo provinces in September and October 2006. Historically, Zimbabweans have been the main migrant laborers on farms in the far north of Limpopo province and Mozambicans in southern Limpopo and the border areas of Mpumalanga. Our objective was to research the human rights situation of foreign migrants and ascertain the extent to which state officials were respecting the protections afforded to them in the immigration law and employers were complying with employment laws for farm workers, and in particular for foreign farm workers.

In Limpopo, Human Rights Watch conducted 43 interviews with farmers and farm workers north of the Soutpansberg around Weipe and Tshipise, and south of the Soutpansberg around Levubu and Vivo; 31 interviews with immigration, military, and police officials, and Zimbabweans awaiting deportation at police stations in Makhado and Musina (the busiest detention center for Zimbabweans in Limpopo); 13 interviews with undocumented Zimbabweans, usually walking on the road en route to Johannesburg; and lawyers (invariably farmers themselves) who advise other farmers on how to comply with the immigration and employment laws. Two local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Nkuzi Development Association and Musina Legal Advice Office, provided research assistance.

Human Rights Watch and Nkuzi Development Association also spent several days at the International Organization for Migration (IOM) reception center in Beitbridge in October 2006. The center provides humanitarian assistance for Zimbabweans deported from South Africa. At the center we talked to IOM staff members to learn more about the operation of the center and to 27 deportees (some of whom had been working not in Limpopo and Mpumalanga but in other locations in South Africa, and who are nevertheless featured in this report) to learn about their treatment during arrest, detention, and deportation, and their employment conditions if they had had jobs.

In Mpumalanga Human Rights Watch worked with the Forced Migration Studies Programme of the University of the Witwatersrand and Nkuzi Development Association, and received assistance from TRAC-Mpumalanga and Masisukumeni Women's Crisis Center. We interviewed in total over 100 people in Mpumalanga. Our interviewees included nine foreign nationals in detention at Komatipoort (the busiest detention center for Mozambicans in Mpumalanga); the only foreign national in detention at Nelspruit; and seven police and immigration officials at Nelspruit, Komatipoort, and Lebombo border post, several of whom were interviewed on multiple occasions. In Nelspruit we also interviewed the Mozambican Department of Labor's sub-delegate, a Food and Agricultural Workers' Union official, a labor inspector in the Department of Labour, and a staff member at the Mozambican recruitment agency Agencia Algos. We concentrated our interviews with 17 farmers or managers and 75 farm workers around Hoedspruit in southern Limpopo, and Hazyview, Kiepersol, and Komatipoort in eastern Mpumalanga.

The names of farmers, farms, and foreign migrants, and on occasion of state officials, are not used, chiefly in the interests of protecting the security of individuals concerned. Many individuals were the victims or alleged victims of multiple human rights abuses by state officials or employers. By withholding names, the report does not, however, reveal the extent to which the same individuals are often the victims or alleged victims of multiple abuses.

A variety of terms are used in legal and other documents to refer to foreign migrants who lack legal status. We use the terminology in South Africa's immigration law, "illegal foreigner," to refer to foreign migrants who enter South Africa without the documents required by the immigration law. Other foreign migrants, and in particular many Mozambicans, hold passports or emergency travel documents that give them the right to reside legally in South Africa. However, the right to be in the country is distinct from the right to work in the country. Mozambicans who are legally in South Africa in terms of the immigration law may be working illegally. Where relevant and known, the work and immigration status of foreign migrants is noted. Otherwise, we use the general term "undocumented migrants" to refer to foreign migrants who lack the legal permission to work or the legal permission to be in the country.

Recommendations

To the Government of South Africa

- The Department of Home Affairs, the South African Police Service, and the Department of Defense should ensure that the correct procedures for arrest, detention, and deportation as set out in the immigration law are consistently followed by state officials. Measures should include improved training of officials in the law and legal procedures; the introduction of a system for undocumented migrants to report on officials who engage in unlawful practices; more rigorous investigation; and prosecution and disciplining of those officials who are found to have committed violations of the laws. In particular:

- The Department of Home Affairs, the South African Police Service, and the Department of Defense should investigate allegations that officials participating in arrests and deportations have been involved in assaults on foreign nationals, and all incidents in which deportees have allegedly been forced to jump from moving trains, and initiate prosecutions where possible.

- The Department of Home Affairs and the South African Police Service should ensure that the practice of detaining minors with adults in violation of constitutional and international legal provisions ceases.

- The Department of Home Affairs and the South African Police Service should improve their internal monitoring of abuses by officials, and include in their annual reports information on the results of their internal monitoring procedures, including how many officials they discipline for abuses relating to foreign migrants, the nature of the abuses, and the kind of disciplinary measures imposed.

- The Department of Home Affairs should formalize and publicize its immigration policy to permit undocumented workers access to their unpaid wages, savings, and personal belongings in the event that they are deported.

- The Department of Home Affairs should amend the immigration law to make it an offense for state officials not to give receipts when they take documents and other items from suspected "illegal foreigners."

- The Department of Home Affairs should develop policy regarding the use of independent oversight mechanisms in immigration detention facilities such as the Judicial Inspectorate of Prisons.

- The Department of Home Affairs should ensure that the detention and deportation procedures at the proposed new immigration detention facility near Musina in Limpopo province developed by the South African Police Service comply with the provisions of Section 34 of the Immigration Act.

- The Minister of Home Affairs should develop the terms and conditions for granting permanent residence status as contemplated by section 31(2)(b) of the Immigration Act for migrants or categories of migrants, including asylum seekers and refugees, for whom special circumstances exist, as in the case of former Mozambican refugees who have failed to obtain permanent residence status during the previous regularization program.

- The Department of Social Development should collaborate with the Department of Home Affairs and the South African Police Service in ensuring that the practice of detaining minors with adults ceases.

- The Department of Labour should ensure that all workers in an employment relationship, whether documented or undocumented, benefit from the provisions relating to conditions of employment as set out in South African employment law, and that these provisions are consistently enforced.

- The Department of Labour should consider introducing a cheaper corporate permit for farmers with small labor forces to offset the current high cost of corporate permits for farmers who only hire small numbers of workers and to encourage the documentation of small workforces.

- The Department of Labour should review, in consultation with farmers, the housing provisions in the Sectoral Determination for the Farm Worker Sector to ensure that this legal provision is not creating a disincentive for farmers to provide housing for farm workers, and if it is, to develop and put in place a remedy.

- The Department of Labour should fill all vacancies for labor inspectors and require labor inspectors to produce public reports with statistics on the numbers of farms they visited, employers and employees whom they interviewed about conditions of employment, violations identified, and employers' compliance and follow-up actions in cases of employers' non-compliance.

- The Department of Labour should create incentives for nongovernmental organizations to assist with independent monitoring of labor laws.

- The Department of Labour should develop a mass public information campaign to educate farm workers and employers about farm workers' rights and the penalties for committing abuse. The information should be disseminated in the languages spoken by farm workers and farmers.

- The Department of Labour should ensure that the right of workers (whether documented or undocumented) injured on duty to receive workers' compensation is enforced, including by imposing penalties on employers who fail to report work-related accidents or violate other aspects of the workers' compensation law.

- The Department of Labour should create and publicize accessible complaints mechanisms for farm workers to report problems such as violence, unpaid wages, or poor working conditions, including hotlines, support for nongovernmental organizations that assist farm workers, and helpdesks at locations frequented by farm workers.

- The government of South Africa should ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights signed in 1994.

- The government of South African should sign and ratify the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, and amend domestic laws accordingly.

To the Parliament of South Africa

- Members of Parliament and the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Labour should pressure the executive to enforce legal protections for foreign migrants.

- Members of Parliament and the Parliamentary Portfolio Committees should ensure that they adequately oversee the functioning of the line ministries that have responsibilities for foreign migrants and farm workers, both foreign and South African. The Portfolio Committee on Labour should ensure that labor inspectors are regularly inspecting farms and issuing the appropriate documents and citations. The Safety and Security Portfolio Committee and the Home Affairs Portfolio Committee should ensure that arrest, detention, and deportation processes comply with the law.

- Members of Parliament and the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Labour should urge the executive to introduce an amendment to the immigration law to enable foreign workers to collect their unpaid wages, possessions, and savings prior to deportation, and propose legislation to encourage the provision of housing for farm workers.

- Members of Parliament should urge the executive to sign and ratify the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, and to ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which provides for the establishment of independent monitoring bodies with a mandate to visit all places of detention.

To Trade Unions

- Trade unions representing farm workers should establish a presence or increase their visibility in rural areas, expand their efforts to educate all farm workers – including foreign migrants – on their rights, and promote all farm workers' interests.

- The Congress of South African Trade Unions should lobby the government to sign and ratify the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families and to ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

To Civil Society

- Civil society should extend its legal services and monitoring to rural areas and work for the protection of all foreign migrants, including farm workers, regardless of nationality.

To Farmer Associations

- Farmer associations should monitor their members to ensure compliance with labor and immigration law.

To Independent Bodies

- The Human Rights Commission and the Commission for Gender Equality should regularly monitor and report on human rights abuses in the farm sector.

- The Legal Aid Board should play a more active role in providing legal services to all farm workers, including foreign migrants.

To the Governments of Zimbabwe and Mozambique

- The embassies/high commissions and foreign ministries of Zimbabwe and Mozambique should prioritize increased protections for migrant workers in South Africa through bilateral diplomacy and increased cooperation with other labor-sending countries. They should conduct information campaigns on workers' rights; create services for workers reporting abuse, including access to legal aid; and track and make publicly available data on the number of migrant workers and reported cases of abuse.

To International Donors

- International donors should provide funding for services for deportees or migrants who are abused in South Africa, support civil society groups in South Africa that promote, monitor, and seek to protect the rights of foreign migrants, and support governmental or civil society public information campaigns on the rights of foreign migrants in South Africa.

To International Organizations

- The International Organization for Migration should urge the governments of Zimbabwe and South Africa to facilitate legal migration by removing current obstacles to Zimbabweans obtaining passports and visas to visit South Africa.

- The UNHCR should collaborate with the International Organization for Migration in Beitbridge to ensure that those who have sought asylum in South Africa are provided protection and the opportunity to return to South Africa.

Background

Recent labor migration to South Africa

Since 1994 the number of documented and undocumented foreign migrants in South Africa has greatly increased. Most migrants come from neighboring countries that are also members of the regional organization, the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Long-term structural and more recent factors have contributed to the growing influx of foreign migrants. Long-term factors include South Africa's long and porous borders with its neighbors, which are difficult to control;1 the "enormous and elastic" potential supply of labor from the SADC member states;2 and South Africa's economic dominance in the region, which makes it an attractive destination for migrants. Newer factors include South Africa's democratic dispensation since 1994, which offers migrants more rights than they can claim in most other countries of the region, and changing conditions in neighboring countries, notably Mozambique and Zimbabwe. While the end of the Mozambican civil war in 1992 halted the stream of refugees into South Africa, it did not reduce economic migration from that country. The political and economic situation in Zimbabwe, which has continued to deteriorate since 2000, has fuelled Zimbabwean migration.3 Today, Zimbabweans are arguably the largest group of foreign Africans in South Africa,4 having recently overtaken Mozambicans, who historically held that position.5

South Africa's policy toward legal and undocumented migration has been about enforcement, control, and exclusion. Immigration policy today, as in the past, promotes the use of temporary foreign workers who are generally not allowed to be accompanied by their families. As in the 1990s, South Africa still seeks to control undocumented migrants through deportations rather than pressure on employers to comply with immigration law.6 Its aggressive deportation policy, despite making substantial demands on financial and human resources, has not been able to stem the increase in undocumented migrants. The media frequently uses an estimate of 5-8 million foreigners without immigration documents, while migration scholars generally agree that the lower end of this range, 5 million, is a reasonable estimate.7

The number of deportations from South Africa has grown significantly in recent years, as Department of Home Affairs (DHA) statistics indicate: 44,225 (1988),8 96,600(1993), 151,653 (2002), 164,294 (2003), 167,137 (2004), and 209,988 (2005).9 Groups monitoring migration have noted that deported individuals often return almost immediately to South Africa, underscoring the limitations of the deportation policy.10

From at least 1990, Mozambicans and Zimbabweans have comprised at least 80 percent of total annual deportations.11 Between 1990 and 2004, more Mozambicans than any other foreign national group were deported, and Zimbabweans were in second place. Since 2005, Zimbabweans and Mozambicans have traded places in the deportation chart, reflecting changes in their relative proportion of deportations that began around 2000. Zimbabwean migrant deportations from South Africa have increased rapidly – approximately 46,000 in 2000,12 74,765 in 2004,13 more than 97,000 in 2005, and almost 80,000 between May 31 and December 31, 2006.14 The increasing number of Zimbabwean deportees has put particular pressure on Musina police station in Limpopo province, which is close to the border with Zimbabwe and is the major point of deportation for Zimbabweans. To accommodate the large numbers of detainees being deported to Zimbabwe from Musina, the South African Police Service is in the process of building an immigration detention facility in Musina.

Rather than helping to contain the numbers of undocumented migrants, a restrictive immigration policy has had the effect of encouraging "a massive 'trade' in forged documentation" and "police corruption as migrants buy the right to stay."15 The process of seeking asylum and of refugee determination has also become enmeshed in corruption in large part as a result of the South African government's efforts to severely limit the number of asylum seekers and refugees.16

A 2006 study commissioned by Lawyers for Human Rights and several other organizations found that Zimbabwean refugees and asylum seekers are especially vulnerable to abuse by various government departments, and particularly by officials in the DHA and the South African Police Service (SAPS).17 The study also revealed a perception among police officers that there is "no war in Zimbabwe," and therefore Zimbabweans could not possibly have a right to political asylum or refugee status.18 Officials' attitudes to Zimbabwean asylum seekers help to explain why at the end of 2005 only 114 Zimbabweans had secured refugee status, while nearly 16,000 Zimbabweans had pending cases.19

Foreign migrant farm workers and commercial farmers in South Africa

Agriculture in South Africa accounts for less than 5 percent of gross domestic product, almost 11 percent of formal sector employment, and nearly 10 percent of South Africa's total exports.20 Continuing a long-term trend, the number of agricultural workers decreased by 152,445 (13.9 percent) from just over 1 million in 1993 to 940,820 in 2002.21 Nearly half of the employees in 2002 were casual and seasonal workers, and their number had increased by 3.2 percent since 1993.22 Despite different methods used to count agricultural employees in the 2002 census and the Statistics South Africa annual labor surveys, the latter also record an ongoing and significant decline in agricultural employment between 2001 and 2005.23

Despite the decline in agricultural employment, there appears to have been an increase in the employment of foreign agricultural workers. The 1996 Farmworkers Research and Resource Project (FRRP) survey of farm workers, the first attempt to document conditions on South African farms, suggested that the employment of foreign migrants in agriculture had increased since 1990.24 This finding is significant because the survey did not focus on border areas or on major migration routes that cross commercial farming districts, where foreign migrants are known to concentrate.25 A 1998 study of farm workers in precisely such areas seemed to corroborate the view that foreigners are providing a larger share of farm labor, noting that "it also seems that border farmers are drawing, perhaps like never before, on cross-border migrants to meet their temporary and seasonal labour needs."26 Border farmers in the Free State draw heavily on labor from Lesotho, those in Mpumalanga and in the south and southeast of Limpopo province on Mozambicans, and those in the northern part of Limpopo province on Zimbabweans.

Often foreign farm workers' de jure status as temporary residents or undocumented residents is at variance with a de facto status as permanent residents. Many foreign farm workers have worked on farms for extended periods of time. The 1996 FRRP survey concluded that over 50 percent of "immigrant farmworkers" had been on the farm for more than five years, about 16 percent for 11-20 years, and some 10 percent for more than 20 years. These findings suggest, as Jonathan Crush notes, "a long-standing pattern of permanent farmwork and residence in South Africa by non-South Africans."27 It is also the case that some farmers will use the label "temporary" even though the farm workers have actually been working full-time and for long periods.

Farm workers, including foreign migrants, have had a right to organize since 1993.28 Whereas nearly 30 percent of the labor force was unionized in 2006, less than 9 percent of employees in the agricultural sector were trade union members. Only employees in private households had lower rates of organization (under 2 percent).29 As in other countries, the agricultural sector is difficult to organize because of low pay and problems of access and communication with workers who are geographically isolated. Employers are hostile to union organizers who must obtain the employers' permission to visit the farms as they are private property, and workers who try to form or join trade unions may face intimidation, violence, and dismissal.30 In South Africa, farm workers' unions also suffer from lack of organizational and financial capacity.31

According to a Statistics South Africa 2000 survey of employment trends in agriculture, "in terms of key socio-economic variables, the situation of people employed in the agricultural sector tends to be less favorable than every other major sector of the economy."32 Human Rights Watch research found that working conditions for many in the sector have improved since 2000, but abuses remain commonplace. Undocumented foreign farm workers remain, as in the past, especially vulnerable to exploitation, despite significant improvements in the legal protections provided for them.33

Commercial farmers face dramatic challenges arising from changes in their business and legal environment. Farmers have had to adapt to the removal of subsidies, protective tariffs, cheap finance, and a labor force whose productivity is compromised by the prevalence of HIV/AIDS. Additionally, farmers face land claims under land redistribution laws and must contend with laws, such as the Extension of Security of Tenure Act, protecting farm residents from arbitrary eviction. A 2001 Human Rights Watch report captures the magnitude of legal and non-legal changes affecting commercial farmers: "Among employment sectors, the 1994 change of government has had perhaps the most profound effect on the working environment of the commercial farmer in South Africa."34 As discussed later, farmers have also had to adapt to legal changes affecting their relationships with their employees and their wage bill.

Mozambican and Zimbabwean farm workers in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces

Nearly 90 percent of Limpopo's 5.6 million people live in rural areas, making it the most rural province in the country.35 About 61 percent of Mpumalanga's 3.2 million people live in rural areas.36 Limpopo is the poorest province of South Africa, with the highest official unemployment rate (32.4 percent) and the worst scores on other poverty indicators.37 More than 33 percent of Limpopo's population aged 20 years and older has not received any form of schooling.38 Mpumalanga compares favorably with Limpopo in these respects: Mpumalanga's official unemployment rate is 27.4 percent and about the same percentage of its population 20 years or older has not had any form of education.39 Limpopo contributed 6.5 percent and Mpumalanga 7.5 percent to the country's gross domestic product in 2003.40 Limpopo's provincial capital is Polokwane (Pietersburg) and Mpumalanga's is Nelspruit.

Over two-thirds of the land in Limpopo and Mpumalanga was allocated for white ownership and use in the past. The vast majority of the population lived in the former homelands – Lebowa, Gazankulu, and Venda in Limpopo and KaNgwane in Mpumalanga – that occupied most of the remaining one-third of the land.41 Though the pace of land reform in both provinces has accelerated, and restitution claims have succeeded or are being adjudicated, the apartheid era's racially discriminatory patterns of land ownership have not substantially altered.42 Most large commercial farms are still owned by whites; black farmers engage mainly in subsistence farming on communal land. Black farmers who engage in commercial farming in the former homelands on land that cannot be privately owned are sometimes referred to as Trust land farmers (they only occupy their land, which is held in trust by the chiefs).

Commercial agricultural production and employment

In Limpopo, north of the Soutpansberg, mainly stock farms and a smaller number of game farms cover most of the land given over to commercial farming. Citrus and vegetable farms are concentrated in the Limpopo Valley, (especially Weipe), Tshipise, and Waterpoort. At the foot of the Soutpansberg, subtropical fruits and a variety of nuts are grown in the Makhado area, including Levubu, and also in Tzaneen. Commercial forests lie on the higher slopes and stock farms are to the south. The province also has private tea estates on land leased from the state, and tobacco farms.43 The province produces about 75 percent of the country's mangoes, 65 percent of its papaya, 36 percent of its tea, 25 percent of its citrus, bananas, and litchis, 60 percent of its avocados, and 60 percent of its tomatoes.44

Mpumalanga's highveld region is dominated by rain-fed grain production. The lowveld region's agriculture focuses on citrus, subtropical fruits, vegetables, and macadamia nuts. Because these crops require irrigation, the farms are close to the major rivers around the lowveld districts of Nelspruit, Barberton, and White River. Transvaal Suiker Beperk (TSB), or Transvaal Sugar Limited, built sugar mills at Malelane in the 1970s and near Komatipoor in the 1980s. Adjacent commercial farms now grow a combination of sugar and one or more varieties of citrus, subtropical fruit (avocadoes, litchis, mangoes, bananas), and vegetables.45 Nelspruit is the second largest citrus-producing area in South Africa and accounts for one-third of the country's exports of oranges. There is extensive commercial forestry along the escarpment around Sabie and Graskop, which provide a large part of the country's forestry products.46

In 2002 (the date of the most recent commercial agriculture census) Limpopo's 2,915 commercial farm units represented 6.36 percent of commercial farm units in the country, and employed 101,249 regular, casual, and seasonal workers. Mpumalanga's 5,104 commercial farm units in Mpumalanga represented 11.14 percent of commercial farm units nationally, and employed 108,083 workers.47 In Limpopo, some 45 percent of full-time workers were women, compared to 62 percent of casual and seasonal workers. The percentage of female casual and seasonal workers was slightly greater (64 percent) in Mpumalanga than in Limpopo, while the percentage of female full-time farm workers (under 30 percent) was lower in Mpumalanga.48 These data indicate the importance of female farm workers, particularly as casual and seasonal workers.

Recruitment and legal status of Zimbabwean and Mozambican farm workers

Foreign farm workers are concentrated on the commercial farms in the border areas of both provinces. Around the late 1960s, farms along the Limpopo border began to rely increasingly on workers who came from the immediate border area. In 1999, before a big influx of Zimbabweans, there were an estimated 15,000 Zimbabwean farm workers, documented and undocumented, north of the Soutpansberg.49 The deterioration of the political and economic situation in Zimbabwe from 2000 onwards led to Zimbabweans from all over Zimbabwe seeking farm employment in South Africa. These migrant farm workers return regularly to Zimbabwe. For some, farm work is merely a stepping stone en route to a job in Johannesburg.50

Farmers north and south of the Soutpansberg who rely on Zimbabwean workers praise their work habits, their ability to speak English, and their level of education (the more recently arrived Zimbabwean farm workers are more likely than in the past to include high school leavers).51 Farmers south of the Soutpansberg who depend on South African labor are hostile to Zimbabwean migrants, holding them responsible for the increase in crime in the province.52 Some farmers talk openly of how they strive to keep their areas "clean of Zimbabweans."53

Lowveld farmers in today's Mpumalanga province have recruited Mozambican farm labor since at least the 1920s.54 In the mid-1980s the Mozambican civil war led to a large influx of Mozambican refugees into the Transvaal, part of which is now Limpopo and Mpumalanga. Approximately 240,000 settled in the homelands of Gazankulu, KaNgwane, and Kwazulu, and most remained there after the end of the war in 1992.55 Unlike other foreign farm workers, these Mozambicans were never migrants but constituted a resident population.56 They became part of the "captive labor pool" of the homelands, but were preferred for work on the farms over South Africans because of a reputation then, as today, for hard work and docility.57 Without legal documents to reside or work in South Africa, the Mozambican refugees joined the vulnerable population of undocumented foreign workers.58

Amnesties affecting Mozambicans

Between 1995 and 1999 the South African cabinet offered three immigration amnesties – in 1995 for foreign migrant miners who had worked on the mines for more than 10 years;59 in 1996 for citizens of SADC countries who had entered South Africa illegally before 1990; and in 1999 for Mozambican refugees60 – through which a total of 197, 125 Mozambicans resident in South Africa received South African identity documents with permanent residence.61 An unknown number of Mozambicans or children of Mozambicans born in South Africa also received South African identity documents with citizenship through marriage, adoption into local families, and integration through the school system.62 It is estimated that about 80 percent of all Mozambicans who are long-term residents of Limpopo and Mpumalanga now have South African identity documents.63 According to Mpumalanga province's head of the Immigration Inspectorate in Nelspruit, the amnesties resulted in "a big part of the workforce" leaving the farms, with most heading for urban areas, and therefore large-scale recruitment of new workers.64

Today the Mozambique Labor Department's sub-delegate office in Nelspruit has 25,000-27,000 Mozambicans who are registered as working legally on farms in Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces. Most of these Mozambicans – around 20,000 – work in Mpumalanga, chiefly in the border areas. In Limpopo, Mozambican farm workers are concentrated around Hoedspruit, Tzaneen, and Phalaborwa. ZZ2, the largest tomato farm in Africa, lies between Tzaneen and Makhado and employs about 1,400 Mozambican workers.65

Institutional differences facing Mozambicans and Zimbabweans

An important institutional difference governs the legal recruitment of Mozambican and Zimbabwean farm labor. Since 1964, a bilateral treaty between Mozambique and South Africa has regulated the recruitment and repatriation of Mozambican mine workers. Today farm workers benefit from a measure of protection provided by institutions established to implement the bilateral treaty for mine workers.66 In particular, there is a private recruiting organization, Agencia Algos, which has an office in Nelspruit. Mozambicans in South Africa can apply for Mozambican passports through Algos, and Algos issues service contracts to be signed by farmers and workers.67 Mozambican workers may also request the Mozambique Labor Department's office in Nelspruit to help with documentation, work-related grievances, and social matters, including the repatriation of deceased workers' bodies or burial arrangements. The labor office also uses at least one nongovernmental organization, Masisukumeni Women's Crisis Centre, to promote and facilitate the documentation of Mozambicans in Mpumalanga.

Unlike Mozambique, Zimbabwe has never had a bilateral treaty with South Africa on the recruitment and repatriation of Zimbabwean workers. Zimbabweans in South Africa, therefore, have no Zimbabwean government labor office or private recruitment agencies to help them obtain documents, mediate workplace disputes, repatriate deceased workers' bodies, and bury workers who die. The governments of Zimbabwe and South Africa are believed to be moving toward signing a bilateral agreement: In October 2004 they signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Employment and Labour to ensure that farm owners in the entire Limpopo province – and not only north of the Soutpansberg – comply with immigration and labor laws.68

Mozambican migrants encounter another institutional advantage over Zimbabwean migrants with respect to visa requirements to enter South Africa. Since April 2005 Mozambicans may enter South Africa for up to 30 days without a visa. Previously, they had to pay R425 (US$60.98)69 for a visa and meet various entry requirements, including having to demonstrate to the South African High Commission (or embassy) that they had accommodation and sufficient funds to support themselves. Since the withdrawal of these requirements, the number of Mozambicans who enter or leave South Africa has doubled from 4,000 per day to 8,000 per day, and tourism has been encouraged. If Mozambicans overstay the 30-day limit – and many do – the DHA may fine them.70

Zimbabweans who wish to visit South Africa for any period, including for short visits up to 30 days, must obtain a visa. The visa itself is free but the South African government requires them to demonstrate that they have R1, 000 (US$143.47) in travelers' checks and must comply with other requirements before they may be granted a visa. The head of the Immigration Inspectorate in Nelspruit said that of all SADC member states' citizens, only Zimbabweans had to meet visa requirements to enter South Africa.71

Zimbabweans also have found it difficult to obtain a passport in a timely manner because of their government's bureaucratic delays. The government of Zimbabwe agreed under the MOU to issue Zimbabwean migrants on farms in the Limpopo with emergency travel documents (ETDs). ETDs are issued more quickly and cheaply than passports but they are not available to most Zimbabwean migrants. In November 2006 the Registrar General's office stopped issuing Zimbabwean passports, already difficult to obtain, because it lacked the foreign exchange to import the ink used.72 The stringent visa requirements and the problems of securing a passport mean that most Zimbabweans who wish to migrate have little option but to become irregular migrants.

International Organization for Migration and Zimbabwean deportees

The IOM has become involved in providing protection for Zimbabweans as a result of establishing a reception center to provide humanitarian assistance to Zimbabwean deportees. Funded mainly by the United Kingdom government's Department for International Development (DFID), the IOM opened the center for deportees at the end of May 2006 in the border town of Beitbridge in Zimbabwe.73

In our August 2006 report, "Unprotected Migrants: Zimbabweans in South Africa's Limpopo province," Human Rights Watch had expressed deep skepticism about the likelihood of the IOM center benefiting Zimbabweans forced to leave South Africa.74 Human Rights Watch had also stated that the IOM's past failure to confront and criticize the Zimbabwean government's human rights abuses in the context of international humanitarian assistance suggested that it would be unlikely to defend deportees' and migrants' rights should so doing require an oppositional stance toward the government of Zimbabwe.

Human Rights Watch had an opportunity to visit the center in October 2006. We were impressed by the assistance that the IOM is providing to deportees and by its efforts to protect the rights of deportees, as we describe below. However, we note that a significant percentage of Zimbabweans reject any IOM assistance, as IOM statistics provided below indicate, and prefer to return immediately to South Africa, as IOM staff themselves acknowledged in interviews with us.75 Zimbabweans will continue to participate in irregular migration for at least two reasons. Firstly, they are unable to obtain employment at home. Secondly, they are unable to obtain passports because the government of Zimbabwe has stopped issuing them and the stringent financial requirements to obtain a visa are beyond the means of the vast majority of Zimbabwean migrants, as discussed above. The IOM should use its working relationship with the Zimbabwe government to pressure it to facilitate "regular" or legal migration by making it possible for Zimbabweans to obtain passports and visas expeditiously and inexpensively.

As explained to Human Rights Watch by IOM officials at the center, on a daily basis the center receives several hundred deportees. Deportees from Lindela (South Africa's detention center, west of Johannesburg, where foreigners awaiting deportation are held) arrive on Thursdays and may number 700 to 1,000. They are transported by train from Johannesburg to Musina police station, and from there to Beitbridge, Zimbabwe by road, either by South African police or immigration officials. Seven days a week deportees arrive by road from police stations in Limpopo province. The deportees attend a mandatory IOM staff lecture to inform them about the hazards of irregular migration, how to obtain passports and visas for South Africa, and what services IOM offers them in Beitbridge so that they can make an informed decision on whether to accept IOM services, including free transport home. The deportees are then processed by the Zimbabwean immigration officials at the newly built police office and immigration office. They may then choose whether to accept IOM assistance. Between May 31 and September 26, 2006, of 47,765 deportees whom South African officials said they had dropped off at the Beitbridge police station in Zimbabwe, almost 50 percent registered to accept IOM assistance, and 92 percent of those who registered availed themselves of transport assistance to their homes.76

Those who seek IOM assistance must provide basic personal information to IOM staff, primarily to facilitate the organization of their transport home or medical or quasi-legal assistance and follow up as required. After registration, the deportees are provided with a free meal. Meanwhile, Corridors for Hope, which is contracted by IOM, provides HIV/AIDS information to the deportees and issues vouchers for deportees to visit the clinic nearest to their homes for free HIV/AIDS testing and counseling. All deportees who seek free transport assistance must also be declared "fit for travel" by one of the two IOM nurses. If the nurses find individuals who require further medical assistance, they are taken to Beitbridge Hospital where IOM pays for their treatment. At the end of each day, the buses that will take the deportees to their homes arrive. Before boarding the buses, the World Food Programme provides deportees with a food pack of 12.5 kilograms of cereal, and when available, 2 kilograms of lentils.77

The IOM holds regular meetings with South African and Zimbabwean government officials at which it raises issues of rights abuses that come to its attention, often from random interviews conducted by its staff members with deportees at the center. Between May 31 and September 26, 2006, the IOM dealt with 20 cases of rape, physical and sexual assault, trafficking, and the deportation of physically and mentally challenged individuals. The IOM has also assisted returned migrants to get their passports back, to report and identify thieves and rapists who operate in the border area and help to bring them to trial, to report officials who have allegedly abused Zimbabweans during arrest or detention, to verify documents of Zimbabweans with a legal right to stay in South Africa and return them to South Africa, amongst other cases. Either the victims or others brought these cases to the IOM's attention and asked it to pursue the cases with South African government officials. Between mid-July and December 31, 2006, the IOM received almost 950 unaccompanied children under 18 years old. These children were referred to the child center, built and maintained by the IOM, financially supported by Save the Children Norway and UNICEF, and under the overall management of the Zimbabwean Ministry of Social Welfare.78

In November 2006 the Zimbabwe state media reported that Zimbabwean police conducted Operation Restore Order from November 13 to November 26 along the Limpopo border to target "cross-border criminals."79 South African media reported that the police had arrested some 2,000 illegal border crossers. In December 2006, there were high-level meetings between South African and Zimbabwean state officials at the Limpopo border on the issue of cross-border crime.80 The program officer of the IOM center believes the police operation was a response to IOM reports about rape, sexual abuse, and deportees' claims of having to pay thieves to cross the Limpopo river.81

The IOM has informed Human Rights Watch that it would like to establish a reception and support center in Mozambique for Mozambican deportees from South Africa. The IOM expects a Mozambican government official to visit its Beitbridge center in Zimbabwe "in the not too distant future." The IOM recognizes, however, that the donor environment in Mozambique is different from that of Zimbabwe, and that it may take longer to establish a facility in Mozambique.82

The Legal Framework

The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, the Immigration Act 2002, and the Sectoral Determination 13: Farm Worker Sector (or basic conditions of employment law for farm workers) provide, for the most part, an adequate legal framework for protecting farm workers' rights. Moreover, the legal framework for farm workers is consistent with the government of South Africa's obligations under those international conventions it has ratified – the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),83 the African Charter for Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR),84 and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).85

The most notable legal gap in the immigration and labor laws affecting foreign migrants arises with respect to the protection of undocumented workers from exploitation. For example, should an employer hire undocumented migrant workers there are no means to ensure that employers will pay the prescribed minimum wage to undocumented migrants, pay them for work performed, or cover them for work-related injuries. If undocumented migrant workers are unable to enforce basic rights arising from their employee status and work that they have performed, then unscrupulous employers may deliberately avoid compliance with South African law to their own advantage, with impunity.

The following discussion of the legal framework highlights key provisions for foreign migrants in the constitution, immigration law, and the basic conditions of employment law for farm workers. We also draw attention to differential rights for citizens and non-South African citizens in the constitution and labor laws, and examine the protections in international conventions which the Government of South Africa has ratified, as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which it has signed but not ratified.86 We also point to constitutional changes that would be necessary should the government of South Africa ratify the ICESCR.

The constitution and the government of South Africa's international obligations

The South African constitution of 1996 came into force in February 1997. It is the supreme law of the country.87 According to the constitution, "[the] Bill of Rights is the cornerstone of democracy in South Africa. It enshrines the rights of all people in our country and affirms the democratic values of human dignity, equality and freedom."88 The Bill of Rights entrenches the rights of "everyone" in South Africa, inter alia, to equality before the law, human dignity, personal freedom and security, privacy, due process of law, freedom of expression and association, fair labor practices, adequate housing, health care, sufficient food and water, and social security.89 With respect to the right to have access to adequate housing and health care, food, water, and social security, the Bill of Rights requires the state to "take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the[ir] progressive realization..."90 The Bill of Rights prohibits slavery, servitude, or forced labor,91 and the deprivation of property (which is not limited to land) except in terms of law of general application.92

Many rights are subject to limitations in the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights expressly limits specific rights to South African citizens: the right to vote, to form a political party, to stand for public office, to obtain a passport, to enter into the country, to freely choose a trade, occupation or profession, and to benefit from state measures to foster conditions that enable access to land.93 The rights in the Bill of Rights may be further limited but "only in terms of law of general application to the extent that the limitation is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society" and "taking into account all relevant factors...."94 The extent to which the constitutional provisions mean that non-South African citizens are also entitled to enjoy the rights such as access to adequate housing, health care, food, water, and social security is yet to be adjudicated by the Constitutional Court, and is therefore an area of unsettled law. For example, the court ruled in 2004 that the provisions of the Social Assistance Act, 1992 (No.59 of 1992) that reserved social assistance benefits for only South African citizens were unconstitutional and had to be extended to permanent residents but not to "illegal foreigners" and temporary residents.95 The Social Assistance Act, 2004 (No.13 of 2004) reflects the Constitutional Court's ruling.

International law and the rights of foreign nationals

Under the constitution, international law must be considered in the interpretation of the Bill of Rights and other national legislation.96 As indicated above, South Africa has ratified the ICCPR, acceded to the ACHPR, and ratified the ICERD. South Africa has signed but not yet ratified the ICESCR. South Africa has not signed the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (Migrant Workers' Convention).97

Most rights provided for in the ICCPR apply to everyone, regardless of immigration status. For example, the ICCPR prohibits the use of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment,98 and slavery, servitude, and or forced or compulsory labor.99 It also provides for the right of everyone to liberty and security of person and prohibits arbitrary arrest or detention;100 requires all persons deprived of their liberty to be treated with humanity and respect for human dignity; and further specifies the segregation of accused and convicted persons and of juveniles from adults.101

The ICCPR reserves a few specific rights for citizens. Only citizens have the right to vote, to have access on general terms of equality to public service, and to take part in public affairs.102 The ICCPR also makes a distinction between the rights of lawful and unlawful "aliens."103 In particular, only legal residents, like citizens, have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose their residence, subject to specific restrictions, including that any restrictions be provided by law.104 The ICCPR also regulates the procedure for the expulsion of a non-citizen legally within the state. A decision to expel a foreigner legally in a country must be in accordance with law. Foreigners legally in the state can only be expelled on the basis of an individual decision taken relating to their expulsion following due process, including the right to submit reasons against their expulsion, to have an opportunity to appeal against expulsion and to have a review by a competent authority.105

Much like the ICCPR, although the ACHPR in the main guarantees everyone – regardless of citizenship or immigration status – fundamental rights, certain rights apply only to citizens and lawfully resident non-nationals. Hence, article 12 stipulates that a non-national legally admitted to a country may only be expelled on the basis of a decision taken in accordance with the law, and prohibits mass expulsions of non-nationals. Article 13(1) and (2) accords only citizens the right to participate freely in the government of their country and the right of equal access to the public service of their country.

The ICERD prohibits racial discrimination, defining it as "any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life."106

States party to the ICERD may differentiate between citizens and non-citizens, provided legal provisions do not discriminate against any particular nationality.107 States party may also adopt special measures to promote the advancement of certain racial or ethnic groups or individuals to ensure such groups or individuals the equal enjoyment or exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms. Such measures will not be considered discrimination provided that they do not lead to the maintenance of separate rights for different racial groups and provided that they are not continued after their objectives have been achieved.108

The ICERD imposes on states party the obligation to condemn racial discrimination and undertake to pursue "by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating racial discrimination in all its forms and promoting understanding among all races."109 States party must also guarantee the right of everyone to equality before the law, notably in the enjoyment of the right to security of person and protection by the State against violence or bodily harm, whether inflicted by government officials or by any individual, group or institution, as well as political, civil, economic, social, and cultural rights.110

In 2004 the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, established under the provisions of the ICERD, adopted General Recommendation No.30, which deals specifically with discrimination against non-citizens.111 General Recommendation No.30 states that differential treatment based on citizenship or immigration status "will constitute discrimination if the criteria for such differentiation, judged in the light of the objectives and purposes of the Convention, are not applied pursuant to a legitimate aim, and are not proportional to the achievement of this aim."112 Other provisions address protection against hate speech and racial violence, access to citizenship, administration of justice, expulsion and deportation, and economic, social, and cultural rights.

For example, states party must take steps to address xenophobic attitudes and behavior toward non-citizens, and take firm action to counter any tendency to target, stigmatize, stereotype, or profile, on the basis of race, color, descent, and national or ethnic origins, members of "non-citizen" population groups, especially by politicians, officials, educators, and the media, and in society at large.113

With respect to ensuring that non-citizens enjoy equal protection and recognition before the law, General Recommendation No. 30 requires that states party "combat ill-treatment of and discrimination against non-citizens by police and other law enforcement agencies and civil servants by strictly applying relevant legislation and regulations providing for sanctions and by ensuring that all officials dealing with non-citizens receive special training, including training in human rights" and "ensure that claims of racial discrimination brought by non-citizens are investigated thoroughly and that claims made against officials, notably those concerning discriminatory or racist behavior, are subject to independent and effective scrutiny."114

International legal standards on rights at work for migrant workers

The ICESCR recognizes a defined set of social, economic, and cultural rights, which states undertake "individually and through international assistance and co-operation" and to the maximum of their available resources, to realize progressively.115 In addition to the progressive realization, and a dependency on available resources, the ICESCR also permits developing countries explicit, but limited, discretion as to the extension of economic rights to foreign nationals. Article 2(3) says, "Developing countries, with due regard to human rights and their national economy, may determine to what extent they would guarantee the economic rights recognized in the present Covenant to non-nationals." If South Africa were to ratify this treaty, the economic rights provided for in the Covenant would therefore not automatically be extended to foreign migrants.

There is considerable overlap between the economic rights contained in the ICESCR and the economic rights provided for in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, which is particularly relevant in light of the imperative that international law inform the scope of the constitutional provisions. Article 7 of the ICESCR, which recognizes "the right of everyone to the enjoyment of just and favourable conditions of work," is reflected in the constitution's guarantee of fair labor practices (section 23). Article 7 explicitly states that such conditions must ensure "(a) Remuneration which provides all workers, as a minimum, with: (i) Fair wages and equal remuneration for work of equal value without distinction of any kind...; (ii) A decent living for themselves and their families in accordance with the provisions of the present Covenant; (b) Safe and healthy working conditions; (c) Equal opportunity for everyone to be promoted...; [and] (d) Rest, leisure and reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay, as well as remuneration for public holidays."116 The ICESCR also requires that working mothers during a reasonable period before or after childbirth should be accorded paid leave or leave with adequate social security benefits.117 Article 7 of the ICESCR also recognizes the right of everyone to social security, including social insurance118 and adequate housing,119 and in these respects is akin to section 27 of the Constitution of South Africa.

However, the ICESCR would also impose new obligations on the government of South Africa with respect to the protection of economic rights. The ICESCR recognizes the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living and, importantly, the continuous improvement of living conditions. As with many other economic rights, states party are required to take "appropriate steps" to ensure the progressive realization of this right.120 While the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa grants everyone the right to a basic education and access to health care services, the ICESCR recognizes "the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health" and to compulsory education free of charge.121

Regarding non-citizens' rights at work, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination's General Recommendation No. 30 states that once an employment relationship has been initiated and until it is terminated, all individuals, whether they have work permits or not, are entitled to the enjoyment of labor and employment rights, including freedom of assembly and association.122 Importantly, as a state party to the ICERD, the government of South Africa therefore has an obligation to ensure that, at minimum, employers must pay the prescribed minimum wages and incur responsibility for work-related injuries of even undocumented workers, including those whom the government seeks to deport.

The ACHPR recognizes the inextricable link between economic, social, and cultural rights and civil and political rights in its preamble. Article 15 of the ACHPR provides that "every individual shall have the right to work under equitable and satisfactory conditions, and shall receive equal pay for equal work."123 In December 2004 the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights124 adopted a Resolution on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Africa.125 The resolution incorporated the Declaration of the Pretoria Seminar on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Africa, which articulates the scope of several of the articles of the ACHPR, including article 15.126 The adopted declaration sets out that the right to work in article 15 of the ACHPR entails among other things:

- Fair remuneration, a minimum living wage for labor, and equal remuneration for work of equal value.

- Equitable and satisfactory conditions of work, including effective and accessible remedies for workplace-related injuries, hazards and accidents;

- Prohibition against forced labor and economic exploitation of children, and other vulnerable persons.

- The right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours, periodic holidays with pay and remuneration for public holidays.127

South Africa is also a member of the International Labour Organization (ILO), the leading international agency setting standards on both the right to work and rights at work. As a member of the ILO, South Africa has obligations to comply with the organization's aims regarding the provision of "decent work" and has a duty to comply with the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (ILO Declaration).128 The Declaration notes that the ILO should "give special attention to the problems of persons with special social needs, particularly the unemployed and migrant workers," and lists the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation as one of the "fundamental rights," which all ILO members have an obligation to protect.

The Migrant Workers' Convention, which South Africa has not signed, provides for the protection of certain rights for all migrants, both documented and undocumented, and of other rights for only documented migrants. Among protections for undocumented workers that are not explicitly provided for in other conventions which South Africa has ratified, article 22(6) requires that deportees "have a reasonable opportunity before or after departure to settle any claims for wages and other entitlements due to him or her and any pending liabilities." Article 32 stipulates that when migrant workers and members of their families' stay in the host country terminates, they must have "the right to transfer their earnings and savings and, in accordance with the applicable legislation of the States concerned, their personal effects and belongings."

The Immigration Act

The Aliens Control Act, 1991, amended in 1996, encouraged and governed permanent immigration for Europeans. African migrants from the Southern Africa region seeking legal access to South Africa were subjected to a dual system of control known as the "two gates policy." The normal immigration rules and regulations for Europeans in the Aliens Control Act of 1991 provided one "gate"; specific exemptions from the act for non-South African workers in the case of bilateral government conventions or temporary employment schemes provided a second "gate." The act did not prescribe or regulate such schemes. It merely gave discretion to the minister of home affairs to exempt particular employers and "special recruitment schemes." These exemptions were designed for the mining industry and white commercial farmers, and allowed them the right to employ non-South Africans under separate terms and conditions than those prescribed by the act.129 The Aliens Control Act was replaced by the Immigration Act, 2002, which became effective in 2003.

The 2002 immigration law was developed by then-Minister of Home Affairs Mangosuthu Buthelezi and his advisors, who were not members of the governing African National Congress party.130 The 2002 act and the accompanying regulations were largely inconsistent with stated government policy to remove obstacles to the entry of skilled migrants. Except for large employers, the 2002 act together with the regulations mostly made the process of entry more complicated and time-consuming.131 Following a 2004 directive from President Thabo Mbeki to the Ministry of Home Affairs to bring the Immigration Act into line with national policy objectives, the Immigration Amendment Act was introduced and became fully operational with the publication of new Immigration Regulations in July 2005.132

The Immigration Act, 2002 (No. 13 of 2002) and the Immigration Amendment Act, 2004 (No. 19 of 2004) empower the minister of home affairs to delegate, subject to the conditions that s/he may deem necessary, his powers (with a few specified exceptions) in terms of the act to other officers or employees in the Public Service.133 The Department of Home Affairs, owing to a shortage of personnel, has delegated powers to the SAPS to conduct searches, arrests, and deportations, and sometimes to the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) to make arrests.134

The Immigration Act, 2002 generally promotes temporary rather than permanent residence and does not encourage family immigration or unification.135 The legislation provides for 13 types of temporary residence permit and five types of work permit.136 Generally, the main consideration in issuing work permits is whether the employer can demonstrate that a South African citizen or permanent resident is not available for the position.137 The employer is also required to demonstrate that the terms and conditions of employment will not be inferior to those applicable for citizens.138 The Immigration Act ends employers' access to special exemptions for the recruitment of foreign workers based on ministerial approval, but preserves existing treaties with governments in the region.139

Farmers who seek to employ foreigners apply to the DHA for a corporate permit, a new type of permit. The DHA determines the maximum number of foreigners the corporate permit applicant may hire.140 Farmers must submit proof of the need to employ the requested number of foreigners and provide a job description and proposed remuneration for each foreigner.141 With a flat fee of R1,520 (US$218.08) irrespective of the number of corporate workers hired, the corporate permit is cheap; individual work permits cost R1,520 each.142 The corporate permit holder must ensure that the passport (or the emergency travel document, ETD) of the foreigner is valid at all times, that the foreigner is employed only in the specific position for which the permit has been issued, and that the foreign worker departs from South Africa upon completion of the job.143

In both Limpopo and Mpumalanga, most farmers with substantial foreign labor forces have applied for corporate permits to legalize foreigners who are already in the country. This is technically unlawful but it does facilitate the regularization of foreigners who are in the country in violation of the immigration law. The Mozambique Labor Department's sub-delegate estimated that only 20 percent of the farmers who come to his Nelspruit office seek to recruit Mozambicans from Mozambique unique the technically correct legal process.144 This official supports the process of documenting workers even if they are already in the country. He believes he was instrumental in persuading the DHA not to deport some 600 undocumented Mozambican workers on tomato producer ZZ2, in Limpopo province. Instead, in December 2005 the DHA, the South African Department of Labour, and his own office with the assistance of Agencia Algos documented the workers. He described the process by which the status of the workers was regularized, albeit not as set out in the law: the DHA issued the company with a corporate permit, after the Department of Labour had accepted that South African workers were not available for the jobs; the Mozambican sub-delegate visited the farm to issue travel documents (for which the workers pay); Agencia Algos provided service contracts (for which the employer pays) after the DHA had issued each worker with corporate worker authorization certificates; then the worker crossed the border into Mozambique to obtain a border stamp in the service contract.145

Another new permit provided for in the Immigration Act is the asylum transit permit. The director-general of the DHA may issue a 14-day asylum transit permit to a person who at a port of entry claims to be an asylum seeker. Within 14 days the asylum seeker must report to one of the country's five Refugee Reception Offices.146 At these offices, all people have the right to apply for asylum and to have their application fairly considered in terms of the Refugee Act, 1998.

The Immigration Act defines a "foreigner" as an individual who is not a citizen and an "illegal foreigner" as a foreigner who is in South Africa and in contravention of the Act.147 Section 34 of the Immigration Act, as amended by the Immigration Amendment Act, governs the procedures for the arrest, deportation, and detention of "illegal foreigners."148 The legislation also forbids employers to hire undocumented foreigners,149 and makes it an offense, punishable by a fine or imprisonment, to hire or aid "illegal foreigners."150

An immigration official requires a warrant to enter a private dwelling to search or make inquiries.151 Farms are ordinarily treated as private dwellings. In early 2002 the minister of safety and security and Agri South Africa (Agri SA), the largest national farmers' organization, negotiated an agreement that requires officials in health, labor, agriculture, home affairs, the police, and defense force to give advance notice to farmers before they visit. Only within 10 kilometers from borders may immigration officials, police, and soldiers visit farms unannounced. Farmers negotiated this agreement on the grounds that people posing as government officials were attacking farm owners.152 According to police and immigration officials, the agreement handicaps them should they wish to visit a farm to investigate whether the farmer is hiring "illegal foreigners." Warned of a pending visit by government officials, a farmer hiring undocumented workers will make sure they are nowhere to be seen when the officials visit.153

Because giving advance warning to farmers is self-defeating, a labor inspector in Nelspruit said labor inspectors did not abide by the agreement: they visited farms unannounced but only concerned themselves with employers who hired "illegal foreigners" if they received complaints of employers' abuse.154 A number of farmers – typically large-scale producers – whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in Mpumalanga reported experiencing blitz inspections.155

Labor laws

The legal environment for farm workers improved substantially, beginning in 1993.156 That year, the government extended the right to organize and the basic conditions of employment law to the agricultural sector. In December 2002 the minister of labour used his power under the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, 1997 (BCE) to set basic conditions for the farm sector, including the introduction of a minimum wage.157 The 2002 Sectoral Determination 8: Farm Worker Sector set minimum wages for March 2003 to February 2004.158 Different minimum wages were set for primarily urban (Area A) and rural (Area B) municipalities.

Sectoral determinations are made for sectors where workers lack the organizational power to ensure adequate protection of their rights through negotiation with employers. The Employment Conditions Commission, which is appointed by the minister of labour and which is composed of a representative of organized labor and organized business, must advise the minister on the impact of a sectoral determination on various matters, including the ability of employers to carry on their business successfully; the operation of small, medium or micro-enterprises and new enterprises; the cost of living; the alleviation of poverty; and the likely impact of any proposed condition of employment on current employment or the creation of employment.159

On February 17, 2006, the minister of labour announced the new Sectoral Determination for the Farm Worker Sector.160 For predominantly rural areas, the minimum wage was raised from R785.79 (US$112.74) per month or R4.03 (US$0.58) per hour to R885 (US$126.97) per month or R4.54 per hour (US$0.65) to apply between March 1, 2006, and February 28, 2007.161 The 2006 Sectoral Determination also set minimum wage increases for 2007 and 2008 respectively, and made a few other changes, including the provision to have only one minimum wage level in the agricultural sector from March 1, 2008.