World Refugee Survey 2008 - Venezuela

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - Venezuela, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50da8d.html [accessed 8 June 2023] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

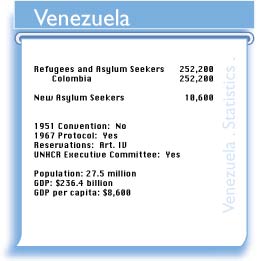

Venezuela hosted some 252,000 refugees and asylum seekers, nearly all of them from Colombia. Colombians fled conflict and persecution stemming from war between government forces and left-wing guerrillas, but also persecution by new paramilitary groups. The majority of 2007 arrivals to the Amazonas region were indigenous people from the Meta, Guaviare, and Vichada regions.

Refoulement/Physical Protection

There were no reports of refoulement, but one immigration office in San Antonio, San Cristobal State, reportedly blocked asylum seekers' access to Venezuela's refugee system unless UNHCR or government authorities submitted written requests to allow it. After complaints to authorities in Caracas, the San Antonio office stopped this practice.

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN) had been fighting over the past year and a half in southwestern and eastern Colombia and could easily cross the porous border to reach several populations of refugees in Guasdualito and other regions. In February, a FARC-ELN clash in Guasdualito killed a four-year-old girl. Venezuelan and Colombian guerilla organizations reportedly intervened in schools, carried out divorces, settled land disputes, controlled the movement of people in the area, determined the hours of operation of petrol stations, and evicted people from homes. Guerillas assassinated opponents and intimidated the civilian population, especially in rural areas. Colombian groups also kidnapped people for ransom and recruited child soldiers in Venezuela.

Venezuela was not party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees but it was to its 1967 Protocol, which incorporated most of the Convention's rights. It reserved, however, the right to favor other foreigners over refugees through regional and sub-regional agreements and exempted itself from the Protocol's grant of jurisdiction to the International Court of Justice. The 1999 Constitution stipulated that human rights treaties the country had ratified had Constitutional hierarchy. In 2001, Venezuela adopted the Refugee Law and adopted accompanying regulations in 2003.

The National Refugee Commission (CNR) oversaw Technical Secretariats (STRs) in Caracas and three cities in border states: San Cristobal, Táchira State; Maracaibo, Zulia State; and Guasdualito, Apure State. The STRs registered asylum seekers who approached the offices, but this was frequently difficult as most asylum seekers lived in remote areas and there were police and military checkpoints on the roads leading to the cities. STR staff did not travel to the major refugee-hosting areas because of security concerns, but UNHCR and its implementing partners did register asylum seekers in remote areas and submit the paperwork to the STRs. Under the Refugee Law, any government or military official could accept asylum applications, but very few besides the STRs and UNHCR did. During the year, UNHCR and the STRs registered 2,230 asylum seekers, while the CNR decided 392 cases. At year's end, there were more than 9,600 pending cases, and despite a stipulation in the Refugee Law requiring a 90-day limit for decisions, the average wait was two years. The delay was due to the limited resources of the CNR and the STR, security concerns over the ongoing conflict in Colombia spilling over into Venezuela, and the fact that the CNR and the STR were both made up of officials from other government institutions whose time was taken up with other duties.

The CNR decided asylum claims, and asylum seekers generally had access to information, legal advice from UNHCR and its partners, and French or English interpreters as needed. There were no special procedures for women, unaccompanied children, or torture victims, and the confidentiality of the proceedings was suspect because CNR's basement office in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was one large, open room with no cubicles or other dividers.

Detention/Access to Courts

While there was no formal detention of refugees for illegal entry or other crimes, members of the National Guard and police regularly extorted money from refugees by detaining and threatening them with deportation and sometimes destroying the refugees' documents. Victims of such detention often failed to report it for fear of provoking reprisals. When it was aware of such detentions, UNHCR intervened directly at the checkpoints in rural areas. In the capital, UNHCR worked through the Government.

The Refugee Law required the CNR to issue provisional documents to asylum seekers when they approached the office, guaranteeing their right to stay in the country until they received a decision on their claims. In practice, however, CNR only referred asylum seekers to the Immigration Office to receive the documents after it had interviewed them, leaving them without documents for months at a time. Only about 55 percent of asylum seekers held identity documents. Additionally, the documents it issued were only valid for 60 days, rather than 90 as the Refugee Law required.

Recognized refugees were entitled to free identity cards from the National Office of Identification and Immigration (ONIDEX) in the Ministry of Interior. It issued these cards only in Caracas, however, meaning refugees without the resources to travel to the capital remained undocumented. Government officials resisted requests to allow issuance in more remote areas, reportedly because of fears that Colombian rebels would obtain cards and gain easy access to Venezuela and concerns over corruption in ONIDEX. Also, the cards gave refugees the status of transeuntes, which the Law of Migration and Immigration (Migration Law) of 2004 eliminated. The Government planned to correct this problem when it issued regulations for the Migration Law. The cards were valid for a year, and allowed refugees to work and attend school.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

There were no refugee camps or official settlements in Venezuela. Although the Constitution guaranteed freedom of movement to all, frequent checkpoints made it extremely difficult for undocumented refugees and asylum seekers to move about the country. UNHCR assisted some of the neediest refugees and asylum seekers in traveling to ONIDEX and STR offices to obtain refugee documents.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

According to the Refugee Law, refugee cards were enough to authorize employment without additional permits. Venezuela also allowed recognized refugees to run businesses and to practice professions, and applied its labor laws to them as to nationals. Most refugees, especially those without identification, and all asylum seekers, worked in the informal sector without the protection of labor laws and tended to receive lower wages than Venezuelans did.

The office of Venezuela's Superintendent of Banks, Sudeban, announced at the end of October that all banks would allow refugees in Venezuela to open accounts with their provisional identity documents or copies of their asylum applications. According to UNHCR, this would also allow refugees to cash checks and transfer money to family members still in Colombia.

Refugees could purchase and own real property, with the only limit being on ownership of land in border areas by foreigners. Because of their lack of identification, asylum seekers had more difficulty in purchasing property.

Public Relief and Education

Refugees in Venezuela had access to health services on par with nationals. UNHCR provided food aid to several refugees and asylum seekers, but they generally benefited from Government programs that provided food and other essentials at subsidized prices.

Although the Refugee Law required a refugee identification card to register children for school, the Ministry of Education promulgated a resolution in 1999 directing that schools enroll all children, regardless of documentation. Some schools remained unaware of this or resisted, however, and some asylum seekers were reluctant to allow their children to attend. Refugees sometimes had difficulty graduating from Venezuelan schools because they could not provide records of their schooling in their homelands. UNHCR provided supplies for nearly 800 schoolchildren in Caracas as well as in rural areas.

In late 2007, a Venezuelan financial public institution, the Banco del Pueblo Soberano, agreed to provide $700,000 in low-interest micro-loans to some 10,000 registered refugees, following an agreement with UNHCR. Microcredit programs, sponsored by UNHCR, for refugees started in Venezuela in 2005 in the three states bordering Colombia: Apure, Tachira, and Zulia. The loans helped purchase seeds and tools for a farm, sewing machines, and tools for car-repair workshops.

UNHCR and Jesuit Refugee Service worked on programs aimed at supporting communities in which Colombian refugees lived alongside Venezuelans.