World Refugee Survey 2008 - Sudan

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - Sudan, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50d3c.html [accessed 8 June 2023] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

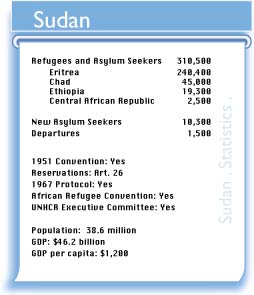

Sudan hosted around 310,500 refugees from its neighbors, primarily Eritrea, Chad, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo-Kinshasa), and the Central African Republic (CAR). Of the roughly 240,400 Eritrean refugees, some 134,500 lived in 12 camps in eastern Sudan. They came mainly during the Ethiopian-Eritrean war, and remained even though nearly 70,000 of them lost their official refugee status after the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) invoked cessation on their prima facie claims to refugee status at the end of 2002. Nearly a hundred Eritreans arrived weekly, most escaping conscription into the Eritrean army.

Sudan gave prima facie recognition to around 45,000, primarily Arab nomadic Chadians who entered its borders after fleeing ethnic clashes in their homeland starting in the 1980s. Ethiopians in Sudan numbered 19,300, of whom some 11,400 lived in the capital and eastern Sudan, while 7,900 ethnic Anouk lived in Jonglei State in the south. Between 2,500 and 4,000 ethnic Goula refugees from CAR sought refuge in Sudan in January, following army reprisals against Goula and other rebel groups. Sudan registered nearly 900 but the rest remained unregistered.

Refoulement/Physical Protection

Sudan deported at least 1,500 refugees and asylum seekers.

In January, Gedaref immigration authorities deported two Ethiopian teenagers whose refugee parents lived in Khartoum. Immigration authorities claimed ignorance of the children's status. UNHCR facilitated their return to the Sudanese border area, after which the agency worked to reunite them with their families. In February, Sudanese police arrested and deported an unknown number of Ethiopian asylum seekers who had sought protection at UNHCR's Khartoum office since December 2006 after Sudan rejected their claims to refugee status. In May, authorities deported six Eritrean asylum seekers from Kassala State. In mid-June, following a court ruling, Sudan deported two Eritrean families seeking asylum, despite UNHCR's urging Sudan to process their applications for refugee status. In mid-July, the Government was reportedly preparing to deport up to 500 refugees to Eritrea the following week, most of them UNHCR-registered residents of Wadi Sherife camp. Police arrested 25 Eritreans and Ethiopians and deported them before UNHCR had a chance to assess their status. In August, Sudan deported 36 refugees back to Ethiopia. Despite reassuring UNHCR that it would not repeat the practice, the following month Sudan handed over at least 15 refugees to Ethiopian authorities at the Metema border crossing. In October, the Government deported 11 Ethiopians allied to the Ethiopian opposition movement. Other deportations went unreported.

In November, UNHCR conducted non-refoulement awareness workshops in eastern Sudan and Khartoum for both central and local officials. Except in security cases, Southern Sudanese authorities generally respected the non-refoulement principle despite the lack of legislation.

There were no confirmed reports of attacks on refugees by foreign agents but an Eritrean opposition source alleged that Eritrean agents abducted Eritreans and took them to Eritrean prisons.

Sudan was party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Convention), its 1967 Protocol, and the 1969 Convention governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (African Refugee Convention), but retained a reservation to the 1951 Convention's right to freedom of movement. The Asylum Act appointed a Commissioner for Refugees (COR), defined refugees generally following the 1951 and African Refugee Conventions, but did not prohibit refoulement, nor did it outline procedures or clear criteria for expulsion. It gave the Minister of Interior or his delegates the right to grant asylum for renewable periods of five years. If the Minister failed to decide on applications within one month, the Asylum Act deemed them granted, for a renewable period of three months. The Asylum Act had no provisions for appeal. UNHCR monitored the Government's refugee status determination.

The 1998 Constitution provided that "everyone who has lived in Sudan during their youth or who has been resident in Sudan for several years has the right to Sudanese nationality in accordance with law," but Sudan did not allow refugees to become permanent residents or naturalize, regardless of how long they had lived in the country.

Detention/Access to Courts

Sudan arbitrarily detained scores of refugees and asylum seekers and charged them with illegal entry and lack of documents under the Passport and Immigration Law of 1993. UNHCR, along with COR, intervened to secure detainees' release, as in the cases of three Eritreans, three Ethiopians, one Cameroonian, and five Somalis.

In January, Sudan arrested a 63-year-old Ethiopian refugee, and held him in Kobar prison, where he remained at year's end. In June, police arrested nine Eritrean refugees during a protest outside UNHCR's office in Al Amarat, Khartoum, but released seven of them. In July, Sudan reportedly arrested about 500 Eritreans. Also in July, the Government arrested more than 30 Ethiopians in Khartoum and Damazine, subsequently deporting 15 and ignored UNHCR appeals for information about the rest. Sudan still held at least three in Kobar prison at year's end. Some of the detainees reportedly belonged to the Oromo Liberation Front fighting Ethiopian forces. In the same month, officials sentenced 13 refugees to three months in Kassala prison for attempting to enter Egypt illegally and refused UNHCR access to them.

UNHCR appointed lawyers to challenge refugee detentions, and in some cases to appeal for reduced sentences.

Obtaining refugee documentation was an expensive, time-consuming, and arbitrary process especially in the east and Khartoum. The Asylum Act required COR to issue renewable identity cards to all refugees valid "for the period during which the refugee is granted permission to stay," i.e., for five years or more. COR, however, issued cards valid from three months to a year.

Nearly 70,000 Eritreans of concern to UNHCR remained without status or documentation after the agency invoked the 1951 Convention's cessation clause in 2002-2004, nullifying their prima facie recognition. Recognized Eritrean refugees who moved from eastern Sudan to Khartoum did not receive cards and most asylum seekers there waited for admission to the Government's registration and asylum procedures. In southern Sudan and Darfur, refugees recognized prima facie did not receive identity cards. Between February and April, COR staff in Girba suspended issuing refugee cards to Kilo 26 camp residents. Refugees had to pay between 1,000 and 2,000 Dinars (about $5-10) per card which many did not have. Asylum seekers did not receive identity cards, although the Asylum Act entitled them to receive documentation.

The 1998 Constitution declared that "all persons" were equal before the law but also provided that "Sudanese are equal in the rights and duties of public life without discrimination based on race, sex or religion." The Constitution extended to all its protections against arbitrary deprivation of liberty, due process provisions, and rights to effective remedies. The Asylum Act allowed authorities to detain refugees "if it is found necessary."

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Sudan required refugees to live in certain areas, designated according to their nationality. Eritreans had to live in the camps in the east while COR screened them, and Ethiopians had to apply for asylum in the capital. Camp residents who had left to find work had to return to renew their cards, unless granted extraordinary permission. In eastern Sudan, asylum seekers could move anywhere in the Wadi Sherife area until the completion of their status determination, but about 80 percent of those arriving in the area left. Although authorities allowed refugees to move to the capital only for educational, medical need, and family reunification, they tolerated the presence of highly-educated Eritrean refugees with identity cards. In southern Sudan and Darfur, refugees recognized prima facie reportedly were free to move in the area.

Most of the estimated 45,000 Chadians in Sudan lived in camps, including Um Shalaya and Mukjar, in West Darfur, but another 16,000 settled on the border to tend their lands. Many Arab Chadians occupied the property of displaced Darfur residents who had fled, especially in the Wadi Azoum and Wadi Saleh areas. In March and June, UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration moved over 1,000 Chadian African refugees from Arara and Beida to Um Shalaya camp, where the local community was of African descent but Arab nomad tribes attacked and robbed them. By the end of August, the camp housed nearly 6,000 and relief agencies could reach it only by helicopter.

Sudan maintained a reservation to the 1951 Convention's right to freedom of movement and the Constitution reserved to citizens its right to freedom of movement. The Asylum Act provided for up to a year in prison for any refugee who left "any place of residence specified for him."

The Asylum Act also allowed the Minister of Interior to provide refugees with passports and, under exceptional circumstances, the Minister of Foreign Affairs to issue them with diplomatic ones. Sudan allowed refugees to travel internationally provided they held refugee cards and valid visas, got UNHCR's recommendation, and had no criminal records.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

Sudan required refugees to obtain work permits to work legally, and its Department of Labour's process for obtaining permits was complex and expensive. Many camp residents waited for years for identification papers to confirm their status and allow them to seek work.

Although provincial governments allowed refugees to farm and work locally, security officials often prevented employers from hiring Ethiopian refugees. Refugees had informal businesses and service jobs, but often at positions below their qualifications. CAR refugees survived by working on private farms or by fishing. UNHCR helped refugees in six camps cultivate crops.

The Government barred refugees from working in state enterprises by requiring military service books. The Government restricted lawyers from practicing, and doctors and teachers needed to obtain licenses from the Ministries of Health or Education. Refugee teachers in camp schools in eastern Sudan could serve only as assistants.

The Constitution was silent on the right to work, but limited to citizens the right to join unions. The Asylum Act forbade refugees from working in security or defense-related industries and required permission from the Department of Labour with notice to the Ministry of Interior to work in any other sector. In July, the Government issued a decree forbidding international organizations in the country from employing refugees except in certain categories.

Legally employed refugees had the same labor and social rights as nationals.

Recognized refugees could engage in self-employment although the Asylum Act did not explicitly provide for it. The Asylum Act forbade refugees from acquiring immovable property but many bought business premises in the names of nationals. Authorities allotted land to some 1,300 refugee families in Um Gargur camp and around 500 refugee families in Abuda camp. They did not receive title but COR issued them letters certifying the land was for their use. Jonglei State authorities also lent land for refugees to cultivate. Um Shalaya residents allowed refugees to cultivate land, for which two NGOs distributed seeds.

Refugees could own bank accounts, and there were no known restrictions on their acquisition of movable property.

Public Relief and Education

The Government in the north was hostile and uncooperative toward UNHCR. Authorities frequently demanded permits, security clearance, and advance notice, and they denied UNHCR access to Wadi Sherife camp in February and March.

In February, after bandits carjacked a UNHCR vehicle near Um Shalaya camp the agency suspended operations for two weeks. At the end of April, gunmen abducted six UNHCR staff and then abandoned them unhurt nearly 100 miles (150 km) away, after which the agency suspended registration at Um Shalaya.

Most of the Chadian refugees in West Darfur brought livestock and supplies with them, but refugees in other parts of Sudan depended on UNHCR. In April, some camps did not receive food rations. Refugees reportedly enjoyed access to the Government's Islamic welfare system.

Refugees had the same access as nationals to local health care facilities. UNHCR maintained free clinics for both locals and refugees in all 12 camps. In Wadi Sherife and other camps in eastern Sudan for Eritrean refugees, the camp hospitals lacked drugs, and residents incurred gastrointestinal diseases by drinking water from the nearby canal. In March, residents of Anuak refugee camp contracted cholera. In August, flooding, unclean drinking water, and poor sanitation caused more outbreaks of gastro-intestinal diseases in Kilo 26, Wadi Sherife, Shagarab, Abuda, and Girba camps. The malnutrition rate in camps reached nearly 16 percent, which along with malaria, respiratory illness, and diarrhea caused abnormally high rates of infant and maternal mortality. In Khartoum, there were three free HIV testing centers but only one in eastern Sudan and no translators for Eritreans and Ethiopians. Anti-retroviral treatment was available in all centers except in eastern Sudan.

Refugees in cities could attend public elementary schools which followed the state Islamic curriculum. Camp-based schools reported an enrollment of only 60 percent, and they often lacked supplies.

Sudan did not include refugees from neighboring countries in its poverty eradication plan.

USCRI Reports

- USCR Urges President Bush to Condemn Khartoum's Genocide and Act Now to Save Hundreds of Thousands of Lives in Darfur (Press Releases)

- Stop the Genocide in Darfur, Mr. President U.S. Official Says One Million People May Die (Press Releases)

- Africa: Nearly 2 Million Uprooted by New Violence in 19 African Countries Last Year (Press Releases)

- Africa: New Displacement of Nearly 3 Million Africans Largely Unnoticed by Rest of World (Press Releases)

- Largely Ignored by International Community, Yearlong Massive Displacement and Death in Western Sudan's Darfur Region Continues (Press Releases)