Deliberate Indifference: El Salvador's Failure to Protect Workers' Rights

| Publisher | Human Rights Watch |

| Publication Date | 4 December 2003 |

| Citation / Document Symbol | B1505 |

| Cite as | Human Rights Watch, Deliberate Indifference: El Salvador's Failure to Protect Workers' Rights, 4 December 2003, B1505, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3fe47b9c4.html [accessed 21 May 2023] |

| Comments | This 110-page report documents serious violations of workers' human rights and examines the role of the government. It features case studies in the private and public sectors, in manufacturing and service industries, and concludes that workers face an uphill battle to exercise their rights, regardless of the sector. Three of the highlighted companies supplied internationally known, U.S.-based apparel corporations. Human Rights Watch found that employers delay salary payments, fail to pay overtime due, deny mandatory bonuses and vacation payments, and pocket workers' social security contributions, preventing them from receiving free public health care. Most pervasively, employers use myriad tactics to violate workers' right to freedom of association. The report calls on El Salvador to strengthen its labor laws by requiring reinstatement for workers illegally fired or suspended for legitimate trade union activity, banning anti-union hiring discrimination, and streamlining union registration requirements according to ILO recommendations. Human Rights Watch urges the Ministry of Labor to uphold workers' human rights by following legally mandated inspection procedures, facilitating rather than obstructing union registration, and refraining from participating with employers in illegal anti-union conduct. |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

I. SUMMARY

Workers' human rights are regularly violated in El Salvador. Because labor laws are weak and government enforcement is often begrudging or nonexistent, employers who flout the law have little worry that they will suffer significant consequences. Aggrieved workers, confronting intransigent employers, an unresponsive Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare (Ministry of Labor), and slow and cumbersome labor court procedures, often settle for minimal, one-time payments. Out of economic necessity, they exchange their human rights for a meager sum to help temporarily support themselves and their families.

Employers have come to see labor rights standards as optional, treating violations as something that can be cured, if need be, with these small payments, a cost of doing business. For workers, the result is a chill on union activity, heightened job insecurity, and, at times, loss of access to affordable health care and other benefits to which they are legally entitled. They are deprived of their right to freedom of association, and their right to health is seriously undermined.

This report uses eight representative case studies to illustrate how workers' human rights in El Salvador are abused with virtual impunity. The cases highlight, in particular, the serious impediments workers face to enjoyment of their right to freedom of association and the failure of the government to provide an effective remedy.

In El Salvador, employers fire trade unionists and leaders, pressure workers to renounce their union membership, use labor suspensions to target union members, and label actual or suspected trade unionists as "troublemakers" and discriminate against them in hiring. Due in part to these practices, only about 5.3 percent of employees in the country have unionized.

Employers also routinely violate local labor laws by delaying salary payments, denying workers mandatory paid vacations and year-end bonuses, and failing to pay overtime. In some cases, employers also deduct social security dues from workers' salaries without paying them to the government, thereby preventing workers from accessing free public health services.

Labor law enforcement in El Salvador is severely inadequate. Resource constraints are one obstacle. For example, thirty-seven labor inspectors reportedly cover a workforce of roughly 2.6 million people. The Ministry of Labor's lack of political will to enforce existing laws and uphold workers' human rights, however, is a much greater impediment to effective enforcement.

The Ministry of Labor's General Directorate for Labor Inspection (Labor Inspectorate) routinely fails to follow legally mandated inspection procedures – conducting inspections without worker participation, denying workers inspection results, failing to sanction abusive employers, and refusing to rule on matters within its jurisdiction. In one case documented below, it also failed to report to the Salvadoran Social Security Institute (ISSS) evidence of social security law violations that prevented workers from receiving free medical treatment.

The Ministry of Labor's General Directorate for Labor (Labor Directorate) routinely ignores employer anti-union conduct and impedes union registration, delaying and, in some cases, preventing union formation, even though it is charged with facilitating the establishment of workers' organizations. In extreme cases, described below, the Ministry of Labor directly participates in employer labor law violations by honoring illegal employer requests that violate workers' human rights.

Moreover, El Salvador's laws governing the right to freedom of association would not adequately protect that right, even if they were effectively enforced. Legal loopholes and shortcomings allow employers to circumvent their obligations under the Constitution and Labor Code to respect workers' right to organize. Worker suspensions can legally be manipulated to discriminate against union members; union registration procedures are excessively burdensome; anti-union hiring discrimination is not explicitly prohibited; public sector workers do not enjoy the right to form and join trade unions; and protections against anti-union dismissals and suspensions are inadequate and easily evaded.

Workers frustrated by the Ministry of Labor's failures and those whose complaints fall outside the ministry's mandate can turn to the labor courts for relief. Judicial proceedings, however, in most cases, not only last longer – at least one-and-a-half years if all rights of appeal are exhausted – but include procedural requirements that may be prohibitively burdensome for workers seeking legal redress. Workers must present a minimum of two witnesses to support their cases, but co-workers often are reluctant to testify out of fear of reprisals from their employers. El Salvador lacks effective "whistle-blower" protection that could quell these fears. Even when workers successfully fulfill the procedural requirements and prevail in court, enforcement of the judgment is, at times, elusive. In other cases, proceedings stall because the defendant employers close their factories and flee and the labor courts cannot find them to serve process. Salvadoran law fails to provide an alternative mechanism, such as the appointment of a curator ad litem, to allow labor court proceedings to go forward when a defendant cannot be found.

Some of the abuses described in this report have taken place in the context of the privatization of public services. All four of the service sector cases documented here involve formerly public industries recently opened for private-sector participation or public enterprises currently under consideration for privatization. Although Human Rights Watch takes no position on privatization per se, we are concerned about the alleged workers' human rights abuses in these cases. These rights violations illustrate the government's failure to include respect for labor rights as a vital component of the economic development program it describes as public-sector modernization.

In other cases, the local companies that abuse workers' human rights are suppliers for larger corporate exporters or licensees or otherwise do business with foreign corporations. This occurred in all four of the manufacturing sector cases examined by Human Rights Watch below – four private employers that reportedly entered, directly or indirectly, into business relationships with at least sixteen corporations, most of them U.S. based. These foreign exporting, licensing, licensee, and distributing corporations profit from the labor rights violations in Salvadoran facilities by transacting in goods produced under abusive conditions. Human Rights Watch believes that such corporations have a responsibility to use their influence to demand respect for labor rights throughout their supply chains. When they fail to do so and benefit from or facilitate workers' human rights abuses, they become complicit in human rights violations.

El Salvador's failure to safeguard workers' human rights in the private export sector not only allows local employers and multinational corporations to carry out and benefit from human rights violations but also helps create a model in which export goods are produced under abusive conditions. As El Salvador's largest trading partner, importing roughly U.S. $2.05 billion annually – approximately 67 percent of El Salvador's exports – the United States has publicly recognized the importance of addressing workers' human rights in the context of its trade and foreign direct investment with the country. And it has taken some steps to do so. Unfortunately, as documented in this report, those steps have been seriously inadequate. The millions of dollars of development assistance the United States has directed to Central American countries, including El Salvador, have failed to address successfully the key obstacles to workers' human rights in El Salvador: inadequate labor laws and lack of political will to enforce them.

The U.S.-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) presents an important opportunity to raise labor standards in El Salvador and throughout the region. Negotiations for CAFTA among the United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua began in January 2003 and are scheduled to conclude in December 2003. Free trade alone, however, cannot guarantee greater respect for workers' rights. Instead, meaningful labor rights protections should be built into CAFTA. The accord should require not only enforcement of local labor laws but that those laws meet international norms. And it should establish a phase-in mechanism to ensure that countries do not enjoy full CAFTA benefits until they effectively implement their own labor legislation.

By permitting legislative impediments to the right to freedom of association and inadequately enforcing the weak existing laws, El Salvador violates its United Nations (U.N.) and Organization of American States (OAS) treaty obligations and its duty as an International Labour Organization (ILO) member to respect, protect, and promote workers' right to organize. By ineffectively enforcing its laws governing employer payments of social security dues, El Salvador impedes workers' right to the "highest attainable standard of health" and, in particular, women workers' right to "appropriate services in connection with pregnancy, confinement and the post-natal period," also safeguarded by U.N. and OAS treaties to which El Salvador is party. Stronger labor rights requirements in CAFTA could pressure El Salvador to fulfill its international obligations to safeguard these rights.

This report is based on an eighteen-day fact-finding mission to San Salvador and Santa Ana, El Salvador, in February 2003 and follow-up interviews and research conducted between February and September 2003. Human Rights Watch's research included interviews with workers; fired and active trade union leaders; non-governmental organization representatives; union organizers; labor lawyers; academics; labor court judges; representatives of business and industry groups; representatives from the government's Human Rights Ombudsman's Office; and current and former Ministry of Labor officials, including the minister of labor. In a few cases, explicitly noted in the text, workers' and current and former government officials' names have been changed, per their request, to protect them from potential employer reprisals. All other names are real and, in the case of workers, union organizers, and union leaders, are included with their express permission to do so, notwithstanding possible negative repercussions for them.

II. PRINCIPAL RECOMMENDATIONS

To remedy El Salvador's failure to uphold internationally recognized workers' human rights, address the actions of corporations that benefit from this failure, and ensure that trade between El Salvador and the United States leads to greater respect for workers' rights, Human Rights Watch makes the following principal recommendations. More comprehensive recommendations are set forth at the report's conclusion.

- El Salvador's Legislative Assembly should amend laws governing anti-union discrimination generally to require immediate reinstatement of workers fired or suspended for legal union activity; to mandate immediate reinstatement of fired trade union leaders, unless prior judicial approval for their dismissal was obtained; and to prohibit employer failure to hire workers due to their involvement in or suspected support for organizing activity.

- As recommended by the ILO, El Salvador's Legislative Assembly should amend the Labor Code to reduce the mandatory minimum number of workers required to form a union; eliminate the requirement that six months pass before workers whose application to establish a trade union is rejected can submit a new application; explicitly permit workers in independent public institutions to form industry-wide unions; and allow all public sector workers, with the possible exceptions of the armed forces and the police, to form and join trade unions.

- The Ministry of Labor's Labor Inspectorate should fulfill its legal obligation to enforce national labor laws and abide by legislation governing its operations. As required by law, the Labor Inspectorate should conduct inspections, upon request, on any matter legally within its jurisdiction and determine compliance with or violation of the law in question; ensure that workers or their representatives participate in worksite inspections; prepare an official document at the conclusion of each inspection and provide all parties a copy of these inspection results; and conduct re-inspections to verify that an employer has remedied all identified violations within the allotted time period and, if not, initiate and conclude without delay the sanctions process.

- The Ministry of Labor's Labor Directorate should uphold its legal duty to facilitate the formation of labor organizations by abiding by its obligation to provide workers fifteen days to remedy any legal defects with a union registration petition and by fully investigating and allowing workers to respond to employer claims regarding founding union members' eligibility for membership.

- El Salvador should ratify the two key ILO conventions governing freedom of association – ILO Convention 87 concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise (ILO Convention 87) and ILO Convention 98 concerning the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining (ILO Convention 98).

- The United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua should ensure that a U.S.-Central America Free Trade Agreement contains strong, enforceable protections for workers' human rights. CAFTA should require that countries enforce their labor laws and that those laws meet international standards and should include a phase-in mechanism that ensures that trading partners do not fully enjoy the accord's benefits until they, in practice, effectively enforce their labor legislation.

- All exporting, licensing, licensee, and distributing corporations, in coordination with their local suppliers, should ensure that international labor rights are respected throughout their supply chains. Corporations should adopt effective monitoring systems to verify that labor conditions in supplier facilities comply with internationally recognized labor standards and relevant national laws. In cases where the facilities fall short, the corporations should provide the economic and technical assistance necessary to bring the local suppliers into compliance within a reasonable time. Only if such assistance fails should the corporations abandon their business relationships with the suppliers. The status of such efforts should be reported publicly at least annually.

III. FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW

Workers' right to organize is well established under international human rights law. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) states that "everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests."1 The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) similarly recognizes "[t]he right of everyone to form trade unions and join the trade union of his choice."2 Likewise, the American Convention on Human Rights provides for the right to associate freely for "labor ... or other purposes," while the Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, "Protocol of San Salvador" (Protocol of San Salvador), guarantees "[t]he right of workers to organize trade unions and to join the union of their choice for the purpose of protecting and promoting their interests."3 These instruments, to which El Salvador is party, establish the right to freedom of association. ILO conventions, recommendations, and jurisprudence, discussed below, flesh it out.

The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (ILO Declaration) has recognized freedom of association as one of the "fundamental rights," which all ILO members have an obligation to protect.4 ILO Convention 87 concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise and ILO Convention 98 concerning the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining elaborate on this right. El Salvador has ratified neither of these core conventions, yet as an ILO member, it has a duty derived from its obligation under the ILO Declaration to abide by their terms. The ILO Declaration states that "all Members, even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question, have an obligation arising from the very fact of membership in the Organization to respect, to promote and to realize, in good faith and in accordance with the Constitution, the principles concerning the fundamental rights which are the subject of those Conventions."5

ILO Convention 87 states, "Workers ... without distinction whatsoever, shall have the right to establish and ... to join organizations of their own choosing without previous authorization."6 Commenting on the legal requirements that labor laws may impose for the establishment of such workers' organizations, the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association has cautioned, "Although the founders of a trade union should comply with the formalities prescribed by legislation, these formalities should not be of such a nature as to impair the free establishment of organizations," nor should they be "applied in such a way as to delay or prevent the setting up of occupational organizations."7

ILO Convention 98 further elaborates on the right to freedom of association, providing:

Workers shall enjoy adequate protection against acts of anti-union discrimination in respect of their employment.... Such protection shall apply more particularly in respect of acts calculated to ... (b) [c]ause the dismissal of or otherwise prejudice a worker by reason of union membership or because of participation in union activities.8

According to the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association, effective protection against anti-union discrimination in employment should cover the periods of recruitment and hiring, as well as employment and dismissal, and is "particularly desirable in the case of trade union officials because, in order to be able to perform their trade union duties in full independence, they should have a guarantee that they will not be prejudiced on account of the mandate which they hold from their trade unions."9

The committee has explained that anti-union hiring discrimination – "blacklisting" – constitutes "a serious threat to the free exercise of trade union rights and, in general, governments should take stringent measure to combat such practices."10 Likewise, governments should provide adequate protection against and remedy for anti-union dismissal. According to the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (ILO Committee of Experts), the remedy should "compensate fully, both in financial and in occupational terms, the prejudice suffered by a worker as a result of an act of anti-union discrimination," and, therefore, "[t]he best solution is generally the reinstatement of the worker in his post with payment of unpaid wages and maintenance of acquired rights."11 Further:

The Committee [of Experts] considers that legislation which allows the employer in practice to terminate the employment of a worker on condition that he pay the compensation provided for by law in all cases of unjustified dismissal, when the real motive is his trade union membership or activity, is inadequate under the terms of Article 1 of the Convention [ILO Convention 98], the most appropriate measure being reinstatement.... Where reinstatement is impossible, compensation for anti-union dismissal should be higher than that prescribed for other kinds of dismissal.12

The ILO Committee on Freedom of Association adds that in cases of anti-union dismissals, governments should also "ensure the application against the enterprises concerned of the corresponding legal sanctions."13

IV. FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION UNDER DOMESTIC LAW

Each State Party to the present Covenant [ICCPR] undertakes to take the necessary steps ... to adopt such legislative or other measures as may be necessary to give effect to the rights recognized in the present Covenant.

– ICCPR, art. 2(2).

El Salvador's Constitution and Labor Code provide that employers, private sector workers, and workers at independent public institutions "have the right to freely associate to defend their respective interests, forming professional associations or unions."14 However, all public sector workers not employed in independent institutions (those that, due to the nature of their operations, enjoy economic and administrative autonomy), such as public hospitals and clinics and the state-owned electric company, do not have the right to form and join trade unions or professional associations.15

The ICCPR and ICESCR permit restrictions on the right to freedom of association only as necessary "in the interests of national security," "public order," or "for the protection of the rights and freedom of others."16 They note, for example, that the covenants "shall not prevent the imposition of lawful restrictions on members of the armed forces and of the police in the exercise of this right."17 The ICESCR adds that such restrictions may also be permissible on workers involved in "the administration of the State."18 ILO Convention 98 similarly states, "This Convention does not deal with the position of public servants engaged in the administration of the State, nor shall it be construed as prejudicing their rights or status in any way."19 The ILO Committee of Experts has explained, however, that restricting the right of workers employed in the "public administration of the State" to form and join trade unions is compatible with international standards only if "the legislation ... limit[s] this category to persons exercising senior managerial or policy-making responsibilities" and "they [these senior workers] are entitled to establish their own organizations."20 This is not the case in El Salvador. Noting that "the denial of the right of public service employees to establish unions is an extremely serious violation of the most elementary principles of freedom of association," the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association, on several occasions, has "strongly urge[d] the Government as a matter of urgency to ensure that the national legislation of El Salvador is amended so that it recognizes the right of association of workers employed in the service of the State, with the sole possible exception of the armed forces and the police."21 El Salvador has yet to comply.

El Salvador further violates both its international treaty obligations and its duty as an ILO member by failing to adopt implementing laws and regulations to enforce the protections for freedom of association set forth in its Labor Code and Constitution. Instead, major weaknesses and loopholes in Salvadoran labor law allow employers to evade their legal obligation to respect workers' right to organize. Worker suspension procedures can be manipulated to target union members; union registration is excessively burdensome; anti-union discrimination in hiring is not explicitly banned; and safeguards against anti-union dismissals and suspensions are weak and easily circumvented.

Weak Labor Laws

Much of the [employer] retaliation is for unionizing. Most of the people who try to unionize are fired. And, later, they [employers] develop blacklists. The workers go to ask for work, and they don't give it to them.

– Labor Ministry official, speaking on condition of anonymity.22

Inadequate Protections against Anti-Union Suspensions and Dismissals

The Labor Code prohibits anti-union discrimination against workers,23 yet El Salvador's laws and procedures fall short of ILO and U.N. human rights standards because they do not adequately give effect to this prohibition. Instead, they fail to protect workers effectively against anti-union suspensions and dismissals, undermining the right to freedom of association and to form and join trade unions.

The Labor Code prohibits employers from firing workers for engaging in legitimate union activity, including labor organizing, but like for all illegal firings, the punishment for violating the provision is a nominal fine. Employers are not required to reinstate fired union members, and the payment due an illegally fired worker is only thirty days' salary – usually about U.S. $144, the minimum wage in manufacturing – for every year of employment.24

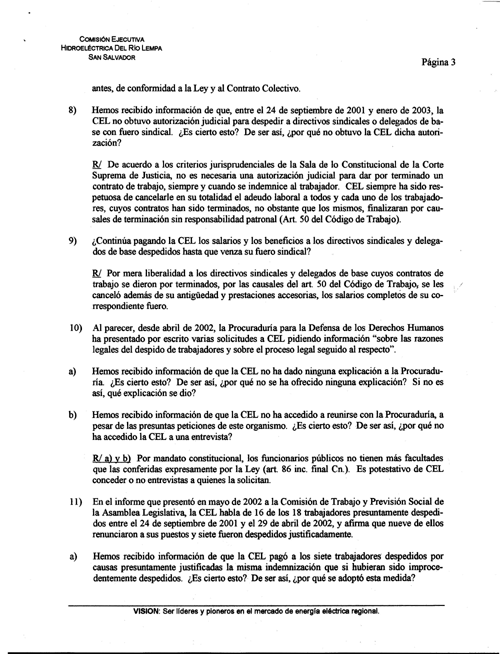

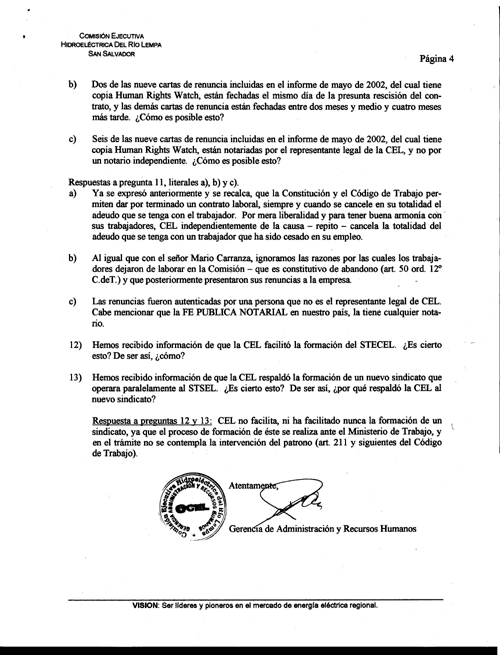

As alleged in the cases of Río Lempa Hydroelectric Executive Commission (CEL) and Lido, S.A. de C.V., detailed in chapter VII below, employers routinely fire union affiliates and pay the small fine for ridding their facilities of trade unionists. Lido reportedly fired thirty union members in May 2002 and another twenty-two between October 14 and November 4, 2002, paying each the low payment due. CEL also reportedly fired roughly thirty-one union members between September 24, 2001, and October 18, 2002. Though CEL claimed that some resigned and others were fired with cause, CEL nonetheless also offered each the minimal compensation owed for illegal dismissal.

Under Salvadoran law, union leaders enjoy greater, yet still insufficient, legal protections. Once they are elected, it is illegal to fire or suspend union leaders without prior judicial approval for one year after their terms expire.25 However, employers are not required to reinstate union leaders fired or suspended without judicial authorization. Instead, employers can legally fire or suspend union leaders so long as they pay their salaries and benefits until the end of the protected period. As an interim justice for the Second Court of Labor Appeals explained to Human Rights Watch, "The principal [legal] obligation of the employer is not to give the worker work but to pay the worker."26 Thus, an employer who bars a union leader from the workplace but continues to pay her as if she were still laboring has not run afoul of the law since the union leader, technically, is still an employee.

As illustrated in the representative cases of Lido and CEL, this is an effective and widely used method of weakening or eliminating unions, as it prevents union leaders from entering the workplace and interacting with other union members. Lido reportedly fired eleven union leaders in May 2002 and, in an agreement reached before the Labor Directorate and reaffirmed in judicial conciliation, agreed to pay them the full compensation owed under the Labor Code, though denying them additional benefits due under their collective bargaining agreement. At this writing, the eleven have not been allowed back in the workplace. CEL also reportedly fired roughly six union leaders between September 2001 and October 2002 and in at least two cases, also agreed to pay their full compensation due. In both cases, the firings severely weakened the unions, as the union leaders could not effectively represent their members while barred from the workplace.

Without the right to reinstatement for anti-union dismissals, existing labor law provisions do not fully protect workers from employer reprisals for exercising their right to freedom of association. One labor lawyer described these hollow safeguards as the commercialization of freedom of association, noting that the financial consequences for violating these provisions are merely a cost of doing business – an investment in a union-free workplace.27

No Explicit Protection against Anti-Union Discrimination in Hiring

El Salvador's laws further undercut workers' right to freedom of association by failing to protect workers against blacklisting – refusing to hire individuals identified on a blacklist as actual or suspected trade union members or supporters. Although the Labor Code prohibits discrimination or retaliation against workers for engaging in union activity, the law defines "workers" as employees or laborers, thereby limiting this protection only to those already employed.28 There is no explicit bar on anti-union discrimination against job applicants or in recruitment, only general Labor Code and Constitutional principles of equality and non-discrimination on the basis of the enumerated categories of nationality, race, sex, or religion.29 To Human Rights Watch's knowledge, no case has yet been presented seeking a legal ruling on whether these principles could be broadly construed also to prohibit anti-union discrimination in hiring. As a result, under the current law, blacklisted job applicants – such as the former Anthony Fashion Corporation, S.A. de C.V. (Anthony Fashions), employees, discussed in chapter VII below – enjoy no legal remedy.

Obstacles to Union Registration

Like El Salvador's laws governing anti-union discrimination, its legislation establishing union registration requirements, according to the ILO, "seriously infringes the principles of freedom of association."30 Although the Constitution provides that the norms governing union formation "should not hinder freedom of association," in 1999, the ILO observed that the "excessive formalities" with which workers seeking to unionize must comply "are contrary to the principle of the free establishment of trade union organizations."31 Among the burdensome formalities identified by the ILO are the Labor Code requirements that six months pass before workers whose application to establish a trade union is rejected can submit a new application; that the union have a minimum of thirty-five members; and that workers in independent public institutions form enterprise-based, rather than industry-wide, unions.32 The ILO has issued recommendations on several occasions since 1999 to streamline union registration "with a view to amending the legislation so that the current excessive formalities that apply to the establishment of trade union organizations are removed."33 None of the relevant provisions has been changed.

Legal Loopholes

Forced Resignations to Circumvent Labor Law Protections

The Labor Code prohibits actions taken to dissolve a union.34 On its face, this prohibition would seem to take a significant step towards counteracting the potentially deleterious effects of El Salvador's weak protections against anti-union dismissals by eliminating one of employers' primary motivations for anti-union firings – union destruction. The Labor Code provides for sanctions of ten to fifty times the monthly minimum wage against employers who fire workers "with the object or effect" of destroying a union and bars dissolution of a union due to insufficient membership, when that low membership is caused by illegal dismissals.35

In practice, however, a legal loophole largely negates any positive impact of this provision because the law is silent on union destruction through employer-coerced resignations. As alleged in the representative cases of CEL, Lido, and the El Salvador International Airport, elaborated in chapter VII, employers may circumvent this Labor Code prohibition by directly or indirectly pressuring already fired or suspended union members to tender resignations, in exchange for full payment of severance due and, often, waivers of all legal claims against the employers. And as alleged in the case of the Industry Union of Communications Workers (SITCOM), also detailed below in chapter VII, employers may pressure actively employed workers to tender their resignations and may use tactics such as withholding their salaries until they do so. If workers resign under pressure or tender retroactive resignations after they have been fired, they are not considered fired workers, and the above-described prohibition, therefore, does not apply. In such cases, workers are faced with the draconian choice of enjoying their right to freedom of association or greater economic stability and money to provide for their families.

Suspensions to Circumvent Labor Law Protections

Employers also flout the weak protections against anti-union firing by using suspensions to coerce worker resignations. They do so legally by exploiting loopholes in the law on labor suspension. Under Salvadoran law, there are eighteen causes for which an employer can legally suspend workers. Eleven can be unilaterally invoked without prior administrative or judicial authorization. One of the most commonly cited is force majeure, defined to include such things as insufficient product orders or "lack of raw material," when the consequences are not the fault of the employer.36 Sometimes these causes are cited legitimately as grounds for suspending operations temporarily, but often they are used to circumvent labor laws governing anti-union dismissals.

A suspension for a force majeure or "lack of raw materials" can legally last for nine months and often creates economic pressures for workers to resign, since workers are unpaid during this period. Workers in these circumstances are usually unwilling or unable to wait out the suspension without pay, hoping for possible reinstatement.37 A former supervisor of labor inspectors noted, "This is a legal hole that the law has regarding automatic suspensions for lack of raw materials. [Employers] use it for various purposes.... They can suspend workers for nine months.... [The workers] are not going to wait nine months."38 As such, these provisions can be and are used as a tool to coerce workers to resign. The head of the Labor Inspectorate of the Ministry of Labor's Western Regional Office in Santa Ana commented that, when an employer wishes to terminate an employment relationship, "An employer should fire, not suspend."39

There is some evidence that employers have cited these grounds selectively against unionized workers, as reportedly occurred in the El Salvador International Airport and Tainan El Salvador, S.A. de C.V. (Tainan), cases, elaborated in chapter VII below. The Union for the El Salvador International Airport Establishment (SITEAIES) was severely weakened when the employer, invoking force majeure, disproportionately suspended union members. Many of the union members, in desperate need of funds, accepted the offer of severance pay in exchange for their resignations and waivers of employer liability. As a Tainan union leader explained to the Ministry of Labor in April 2002 when Tainan began suspending, rather than firing, workers, "[The employer] knows that the majority of these [suspended workers] are affiliates of our union and that, in the face of the uncertainty of a suspension in the terms set forth by the company, [they] will choose to receive the money that the company offers" in exchange for submitting their resignations.40 By using suspensions to pressure union members to resign, rather than firing the workers directly, employers circumvent both the bans on anti-union dismissals and on firing workers in an attempt to destroy a union.41

V. MINISTRY OF LABOR FAILURE TO ENFORCE LABOR LAWS

I, on the inside, ask, "What happens here? Why don't we prevent these violations?" ... We are not going to do it, in the end, because we should not discredit an employer. We need our jobs. We have to let everything go.

– Labor Ministry official, speaking on condition of anonymity.42

The Ministry of Labor's Labor Inspectorate fails to follow proper inspection procedures, seriously compromising workers' right to an effective remedy for violations of their human rights.43 It conducts inspections without worker participation, denies workers inspection results, fails to impose employer sanctions, and refuses to rule on matters within its mandate. The Ministry of Labor's Labor Directorate ignores employer anti-union conduct and impedes union registration, delaying and even preventing the establishment of workers' organizations in violation of international norms.44 In extreme cases, the Ministry of Labor participates in employer labor law violations by honoring illegal employer requests that violate workers' human rights.

There are a number of reasons for the failures described in this chapter. Resource constraints are one obstacle to adequate labor law enforcement; thirty-seven labor inspectors reportedly cover a labor force of roughly 2.6 million.45 Of far greater concern is the demonstrated lack of political will of existing Ministry of Labor supervisors and other officials to insist on compliance with domestic labor laws. As a former labor inspector and current labor law professor explained to Human Rights Watch, "There is no political will to enforce the country's laws.... You can see the cultural climate of not bothering the big companies.... We fined the small bakeries, the mechanics shops – ... small businesses, but not the big ones."46 A justice from the Division of Disputed Administrative Matters of the Supreme Court similarly told Human Rights Watch, "the maquila is very much protected here.... The Ministry of Labor is very political.... It does not apply the law, but politics."47

Although workers who believe that the Labor Ministry acted illegally in their case – for example by failing to follow mandatory procedures or inaccurately interpreting and applying the law – may appeal to the Division of Disputed Administrative Matters of the Supreme Court, the process is so long and cumbersome that few workers have the time or resources to make use of it.48 According to a justice who serves in this appeals section, rulings in such cases, on average, take roughly one-and-a-half years. He reflected, "We are very slow here. Something that should be done in four months, we do in a year."49 One advocate for workers' human rights similarly explained, "the problem is that people see that the procedures are so long and complicated that they don't turn there."50

Legal Obligations of the Labor Inspectorate

Under Salvadoran law, the Labor Inspectorate is charged with "ensuring compliance with statutory labor provisions and basic norms of occupational health and safety."51 The Labor Inspectorate is based in San Salvador, with representatives in a Western Regional Office in Santa Ana and an Eastern Regional Office in San Miguel, and is divided into two departments – the Department of Industry and Business Inspection and the Department of Agriculture Inspection.52 There are twenty-seven inspectors in San Salvador, four in Santa Ana, and six in San Miguel.53

The Law of Organization and Functions of the Labor and Social Welfare Sector (LOFSTPS) establishes Ministry of Labor rules of operation. The law provides that the Labor Inspectorate shall include supervisors and inspectors, who shall conduct programmed and unprogrammed worksite visits – the former part of monthly plans of preventive inspections and the latter, usually solicited by interested parties, in response to specific events "requiring immediate and urgent verification."54

All such worksite inspections are to be conducted in accordance with established legal procedures. The workplace visits "will occur with the participation of the employer, workers, or their representatives."55 A legal document – an Acta – must be prepared in the workplace at the conclusion of the inspection, detailing the violations and establishing a time period, not to exceed fifteen days, within which violations must be remedied. An inspector is required to meet with both parties prior to preparing the Acta to discuss steps to be taken to remedy the violations identified and to present the document to both parties to sign if they choose.56 A follow-up inspection must be conducted after the time period for remedying the violations expires. If the follow-up inspection reveals that an employer is still not complying with the law, an inspector must prepare another Acta and turn the case over to higher Labor Inspectorate authorities to levy the corresponding fines. Extending the fifteen-day time period is not allowed.57

The Labor Inspectorate, however, often fails to follow these explicitly mandated inspection procedures. The result is an inspection process that rarely provides effective redress for workers whose rights have been violated and presents little credible threat of punishment for employers who violate those rights.

Failure to Allow Worker Participation in Inspection Visits

They [labor inspectors] didn't ask us anything.... They would stay behind the [production] lines but not ask us how the situation was.

– Carla Cabrera, Anthony Fashions assembly line worker whose name has been changed for this report.58

Salvadoran law directs inspectors to meet with both employers and workers when they conduct inspections.59 Human Rights Watch found, however, that in many cases, inspectors fail to interview workers, basing their findings solely on employer testimony and potentially flawed company records. This is particularly common when workers allege economic violations, such as a failure to pay salaries, vacation benefits, social security, or legally mandated end-of-the-year bonuses. According to Rolando Borjas Munguía, director general of the Labor Inspectorate, in such cases, "they [inspectors] don't speak with workers.... They just look at the records."60 The Salvadoran Social Security Institute case, discussed in chapter VII below, illustrates this widespread problem; doctors who brought a complaint against their employer were first notified of the inspection twenty-one days after it occurred and were never interviewed.

Despite legal provisions mandating that workers or their representatives participate in worksite visits,61 inspections commonly take place without their presence. Union leaders and workers' lawyers complain that they are not informed when inspections are to be conducted, particularly in cases involving dismissals or suspensions, even though they specifically ask to be contacted in the inspection requests. "We want to be present," a labor lawyer explained, but "they never notify us."62

Despite the legal requirement,63 none of the labor inspectors whom Human Rights Watch interviewed thought that complainant workers or their representatives must be present during an inspection. One supervisor for the Department of Industry and Business Inspection told Human Rights Watch, "You almost don't see cases when the workers are there."64 Similarly, the supervisor of labor inspectors in the Ministry of Labor's Western Regional Office in Santa Ana explained, "An Acta is prepared if the worker is not present. It says that [the worker] did not sign because he was not present when the inspection was conducted, and it is still valid."65 A former supervisor of labor inspectors, speaking on condition of anonymity, added, "If inspectors do not think it's necessary to speak with the workers, they don't speak with them. They conduct the inspection though the [complainant] worker is not there."66

Failure to Provide Workers Copies of Inspection Results

It's a policy of denying them [workers] information – a policy of hiding information.... You see the bad faith of the ministry in these cases – the transparency of an entity of the state that should be enforcing labor laws.

– Antonio Aguilar Martínez, associate ombudsman for labor rights.67

As workers are often not interviewed during an inspection and may not even be present, they frequently miss the opportunity to obtain a copy of inspection results while the inspector is still in the workplace. In such cases, complainant workers submit a request to the Ministry of Labor if they want a copy of the results. When they do so, they may be illegally denied access to the inspection document, as alleged in the representative cases of Anthony Fashions, CEL, and the Salvadoran Social Security Institute, discussed in chapter VII below. As one Ministry of Labor official acknowledged, speaking on condition of anonymity, "The affected workers have a right to receive the Acta, [but] they have to ask for it in the moment [of the inspection]. Later, they are not going to want to give it to them."68

Without inspection results, workers whose complaints are found to be without merit are denied a justification for the decision. Even in cases where workers prevail in part or in full, failure to provide inspection results denies them evidence that could provide essential support in subsequent court actions against their employer. In the Anthony Fashions case, the denial of inspection results deprived workers of evidence of precisely how much their employer owed them; their criminal complaint against the company for wrongfully withholding their bonuses subsequently was dismissed for lack of evidence.69

When questioned about this illegal practice of denying workers copies of inspection results,70 the Labor Inspectorate has offered at least two different justifications – one to Human Rights Watch and the other to workers and their representatives. Both explanations have no basis in law. Instead, they are legal fictions invented to justify government-erected obstacles that impede workers' right to obtain legal redress when their human rights are violated.

When Human Rights Watch asked Rolando Borjas Munguía, director general of the Labor Inspectorate, why, in some cases, the Labor Inspectorate refuses to provide complainant workers copies of inspection results, he explained that only when those workers are present for the inspection are they entitled to a copy of the Acta. If they are not present, he said, the inspector "drafts a report that is our information and confidential. An Acta cannot be prepared if the complainant is not there.... Like the Acta, it [the report] documents if there is a violation or not and establishes a period within which to remedy it."71 The implication of Borjas' statement appears to be that if inspectors violate the requirement that complainant workers or their representatives participate in inspections, they must also violate the requirement that an Acta be prepared at the conclusion of each inspection and provided to interested parties.

Other Labor Ministry officials not present during Human Rights Watch's interview with Borjas, however, stated that the law does not allow for such substitution of a confidential report for an Acta.72 The other Labor Ministry representatives unanimously concurred that even if complainant workers do not participate in inspections, they have a right to a copy of the results. For example, the head of the Ministry of Labor's Western Regional Office in Santa Ana commented that, in such cases, absent complainant workers "can ask for a copy of the Acta. They have a right to a copy.... They have the right to know what the ministry does.... It is a [confidential] report only when an inspection was not performed."73 The supervisor of labor inspectors of Santa Ana similarly added that if a complainant worker is not present for the inspection but "later wants a copy of the Acta, it is turned over. If we didn't, this would leave [the worker] at a disadvantage. Imagine, he wouldn't have a copy of the Acta for another process."74

Asked to comment on Borjas' explanation to Human Rights Watch, the judge for the First Labor Court of San Salvador responded, "The report – they have invented that. They should prepare an Acta.... They make it [the report] confidential, but it should not be confidential. It does not have to do with private things.... A report should complement an Acta, but not replace it."75 The associate ombudsman for labor rights similarly explained, "It's a lie that it [inspection results] is not turned over because it's a report."76

The Labor Inspectorate has regularly provided a very different explanation to workers for denying them access to inspection results. Workers told Human Rights Watch that, instead, the Labor Inspectorate invokes articles 39b and 40a of the LOFSTPS law described above and article 597 of the Labor Code. LOFSTPS article 39b requires inspectors to "maintain strict confidentiality with respect to any complaint about which they have knowledge regarding a violation of a legal provision," and article 40a prohibits them from "revealing any information about affairs subject of an inspection."77 Labor Code article 597 establishes that legal documents prepared by the Labor Inspectorate "will not be valid in labor cases or conflicts."78

This explanation is also flawed. The Labor Code article cited is irrelevant to whether complainant workers have a right to a copy of inspection results. And the interpretation suggested for the LOFSTPS articles ignores both common sense and a basic rule of statutory interpretation – the principle of internal consistency. LOFSTPS cannot require that inspection results be discussed with parties to a complaint, that those parties be provided an opportunity to sign the document setting forth the findings, and at the same time, prohibit disclosure of those results to the same parties. Furthermore, in many cases, complainant workers have been provided copies of inspection results.

When Human Rights Watch questioned a former supervisor of inspectors about the interpretation offered by the Labor Inspectorate of LOFSTPS articles 39b and 40a, he replied that those articles "refer to people who have nothing to do with the worker.... [The Labor Ministry's construal] is a very superficial interpretation due to ignorance or malice."79 A labor law professor and former labor inspector similarly concluded that such an interpretation "is illogical. It's as if you went to the doctor and he didn't tell you what you have."80

Failure to Enforce Inspection Orders and Impose Sanctions

Generally, they [Labor Ministry officials] don't impose fines, even when they find that a violation has not been remedied.

– Carlos Aristides Jovel, judge, First Labor Court of San Salvador.81

Both the labor minister and a supervisor of labor inspectors for the Department of Industry and Business Inspection in San Salvador told Human Rights Watch that the Labor Inspectorate does not extend the period within which an employer must remedy identified violations.82 The minister stated categorically, "If the time period expires, that's final."83 Human Rights Watch found, however, that inspectors often fail to impose sanctions and illegally increase the time periods provided for employers to remedy labor law violations.84

In some cases, the time period is suspended indefinitely and inspectors' orders are never enforced, as allegedly occurred in the Tainan case, discussed in chapter VII. Inspectors declared worker suspensions at Tainan illegal, ordered the company to pay suspended workers' back wages, but reportedly failed to sanction the company when it failed to do so. At this writing, almost two years later, workers have yet to receive their money due. In other cases, as explained by the head of the Ministry of Labor's Western Regional Office, if ministry officials can persuade employers to remedy violations, they will extend the deadline for them to do so without imposing fines. He clarified, "We believe that we can be flexible."85 The supervisor of labor inspectors for the same office similarly explained, "If [the employer] demonstrates the will to resolve the problem, we give a new time period, trying to maintain harmony among the workers, the employer, and the institution. Otherwise, we would be an institution like the police."86 A labor inspector for the Department of Industry and Business Inspection in San Salvador also implied that the time period established by an inspector for remedying a violation is flexible, saying that only "if in the follow-up inspection the [employer] does not show the will to pay [money owed], is the sanctions process initiated."87

A former supervisor of labor inspectors from the Department of Industry and Business Inspection in San Salvador related to Human Rights Watch a November 2000 case that illustrates this problem:

I went to perform an inspection at a company in response to a complaint that they didn't pay salaries or benefits. The head of the company then requested a meeting with Borjas.... The director [Borjas] talked to me, and I went to the meeting. The owner asked for more time, a longer period than I had given in the Acta. Borjas gave the company more time – two more months. The first thing he did wrong was to override the Acta. Then ... the owner of the company told him that a union had formed in the company and asked him what to do about it. Borjas said to fire all the union leaders.88

Failure to Rule on Alleged Violations and Misapplication of the Law

In some cases, inspectors conduct inspections but fail to issue findings on any or all of the labor law violations alleged in the inspection request, as in the Confecciones Ninos, S.A. de C.V., and El Salvador International Airport cases, described in chapter VII. In other cases, inspectors improperly apply the law, as also occurred in the case of the El Salvador International Airport. In still other cases, particularly those involving worker suspensions, inspectors may declare certain matters outside their jurisdiction, even when the issues are within the Labor Inspectorate's legal mandate, as illustrated here by the Anthony Fashions and Tainan cases.

Not only does Salvadoran law authorize inspectors to determine the legality of worker suspensions, but every inspector to whom Human Rights Watch posed the question agreed that the issue is within the Labor Inspectorate's jurisdiction.89 The judge for the Third Labor Court of San Salvador similarly explained, "They [inspectors] can document [the underlying facts]. They can impose a fine. They can verify whether the suspension is legal or illegal."90

When inspectors fail to rule on allegations of labor law violations, misapply the law, or declare certain matters outside their jurisdiction, they force workers to turn to labor courts if they wish to challenge the legality of employer conduct and seek legal redress. The judicial process, in most cases, however, lasts longer and is more arduous than the Ministry of Labor's administrative procedures.91 Furthermore, for suspended workers who have no income, time is of the essence. Economic necessity may press suspended workers to resign before judicial proceedings are completed and accept whatever compensation package may be offered. Thus, in the case of worker suspensions, by declining to rule on the legality of employer conduct, the Labor Inspectorate increases the pressure on suspended workers to resign and helps employers take advantage of legal loopholes, detailed above, to circumvent workers' human rights protections, like those governing the right to organize.

Participation in Labor Law Violations: Granting Illegal Employer Requests

In some cases, the Ministry of Labor indirectly participates in employer abuses of workers' human rights and labor law violations by honoring illegal employer requests that harm workers.

As noted, employers may require fired workers to sign resignations in exchange for their severance pay in order to circumvent Labor Code protections against anti-union dismissals and firing workers to destroy a union. Employers may also demand that workers confess to participating in certain activities, like workplace violence, or make written promises, such as to forgo strikes, as a condition for collecting their salaries. Commenting on such practices, a Labor Ministry official speaking on condition of anonymity told Human Rights Watch, "In practice, they do it, but it is not legal. It should not be done."92

It is illegal for employers to impose conditions on the payment of salaries or benefits already owed to workers. Labor law requires employers to pay each worker her salary, defined as "the monetary consideration that the employer is obligated to pay to a worker for the services provided," and the Constitution establishes workers' right to earn a minimum wage and prohibits the withholding of workers' salaries and benefits.93 Similarly, both the Labor Code and the Constitution establish that a worker fired without just cause has the right – with no additional conditions attached – to severance pay from her employer.94

Actions by employers that violate these legal provisions are bad enough in themselves, but the situation is made worse by the fact that employers sometimes enlist the assistance of Ministry of Labor personnel in such schemes and that the Ministry of Labor personnel acquiesce. Under certain circumstances, employers choose to deposit salaries and other payments owed to workers with the Ministry of Labor. In some such cases, employers who seek to force out particular employees or impose specific terms on them ask the ministry to honor requirements that workers tender resignations, confessions, and the like as a condition of receiving salaries and other benefits that they have already earned. As documented in chapter VII, the Ministry of Labor sometimes does so.

Obstacles to Union Registration

Under Salvadoran law, the Labor Directorate is legally obligated "[t]o facilitate the constitution of union organizations and comply with the functions that the Labor Code and other laws set out with respect to their management and registration."95 As such, it is responsible for reviewing and assessing petitions to register workers' organizations and implementing and applying El Salvador's many requirements for registering a labor organization.

In violation of international law,96 the Labor Directorate tends to interpret these requirements narrowly, creating obstacles to the right to organize – unless the union is employer supported, in which case the Labor Directorate tends to apply an expansive interpretation, facilitating union registration. The Labor Directorate may also look the other way when anti-union conduct prevents workers from exercising their right to organize, despite Labor Code provisions that prohibit employers from "trying to influence workers regarding their right to association" and "taking actions that have as their goal impeding union formation."97

In the Confecciones Ninos and SITCOM cases, detailed in chapter VII below, the Labor Ministry arbitrarily rejected applications for union recognition when it accepted the employers' accounts of the underlying facts without first investigating workers' claims that would have supported the validity of the applications. In contrast, in the CEL case, the ministry reportedly granted legal personality to an employer-supported union without investigating allegations that its members had failed to resign from the independent union first, in violation of the Labor Code's prohibition on dual union membership.98

Ministry of Labor practices in this area have drawn court censure. For example, on March 29, 2000, the Division of Disputed Administrative Matters of the Supreme Court ruled that the Ministry of Labor acted illegally when it denied the registration petition of the Union of Workers of the Tourism, Hotel, and Similar Industries on June 26, 1998. The Supreme Court found that the Ministry of Labor misinterpreted the Labor Code to bar workers in independent public institutions from forming industry-wide unions; failed to follow mandatory procedures when it cited shortcomings in the union's petition without giving workers the mandatory opportunity to remedy them; and misapplied the law to the facts when it held that the union failed to describe employers' activities, the union's purpose, and the activities of the founders. The Supreme Court – over two years after the illegal denial of the union's petition – ordered the Ministry of Labor to "issue a new resolution that orders the denied registration."99

Again, on August 25, 2000, the Division of Disputed Administrative Matters of the Supreme Court held that the Ministry of Labor had illegally denied union registration, this time to the Union of the Unit of Workers of the Telecommunications Company of El Salvador, S.A. de C.V. (SUTTEL), on June 16, 1998. The ministry reportedly rejected SUTTEL's registration petition – without first providing the workers the mandatory fifteen-day opportunity to remedy the shortcomings – on the grounds that it was presented within six months of a prior petition from the same workers and failed to set forth the union's purpose. The Supreme Court rejected these grounds. It found that the registration petition sufficiently set forth the union's purpose as "representing the interests and rights of the affiliates and members," paraphrasing language directly from Labor Code article 229, and that the forty-four workers who formed SUTTEL on May 24, 1998, were different from those who attempted to unionize on January 2, 1998. The Supreme Court ordered the ministry to "issue a new resolution granting the legal personality denied and list the union in the respective registry" – once again, over two years after the workers' initial attempt to unionize.100

Also in 2000, in the case of the Trade Union Federation of Food Sector and Allied Workers (FESTSA), the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association stated, "The Committee deeply regrets that, given that the problem [denial of legal personality] arose from procedural errors which could easily have been rectified, the authorities did not attempt to obtain the further documentation or information required by asking the founders of the Federation to rectify procedural anomalies found in the constituent document within a reasonable period."101

Deprivation of Access to Health Care

In some cases, employers deduct social security payments from workers but then fail to submit the funds to the Salvadoran Social Security Institute, as required by law. As a result, those workers and their families are uninsured and have been turned away from government-run health clinics. Because many of the workers are poor, it is difficult or impossible for them to afford private health care. When forced to pay, they and their families may simply forgo needed treatment. The government's response in such cases has been inadequate. Its failure to prosecute these cases vigorously, report evidence of such violations immediately to the ISSS for investigation, and create a mechanism so that affected workers can obtain timely access to clinics violates workers' right to health.

The right to health is recognized as an economic and social right whose full realization must be progressively achieved under international human rights law. The ICESCR provides for "the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health" and obliges states parties to create "conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness."102 Similarly, the Protocol of San Salvador establishes "the right to health, understood to mean the enjoyment of the highest level of physical, mental and social well-being," and requires states parties to make "[p]rimary health care, that is, essential health care, ... available to all individuals and families in the community" and to extend "the benefits of health services to all individuals subject to the States' jurisdiction."103 The Protocol of San Salvador further mandates that states parties adopt "such legislative or other measures as may be necessary for making those rights a reality."104 The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) adds that states parties must also "ensure to women appropriate services in connection with pregnancy, confinement and the post-natal period, granting free services where necessary."105

El Salvador's Constitution recognizes the "obligation of the State to ensure to the inhabitants of the Republic enjoyment of ... health" and establishes social security as an "obligatory" institution of "public service."106 Under Salvadoran law, employers are required to insure their workers by depositing monthly with the Salvadoran Social Security Institute employer dues and worker contributions, deducted from employee salaries.107 Upon presentation of their "Affiliation Cards" and "Employer Certificates" or "Certificates of Rights and Payments," workers, their spouses, life partners, and children are eligible for free ISSS health services, including "necessary care during pregnancy, child birth, or post-partum."108 Employer delay in making social security payments is punishable with up to a 10 percent surcharge of the total amount due.109

Inspectors from the ISSS Department of Affiliation and Inspection oversee enforcement of the Social Security Law and its regulations.110 According to several Labor Ministry officials, when labor inspectors uncover employer violations of social security obligations, they also notify the ISSS inspection department.111 Thus, in theory, two bodies of inspectors – from the ISSS and from the Labor Inspectorate – coordinate to ensure the effective application of Salvadoran laws governing social security.

In practice, however, this may not occur. As illustrated in the representative case of Anthony Fashions, described below in chapter VII, even when the Labor Inspectorate has evidence of employer failure to comply with social security laws, it may fail to inform the ISSS or take any steps to remedy the situation. The result, as in the Anthony Fashions case, is that workers – some of whom are pregnant – may face significant obstacles to the enjoyment of their right to health. Unable to access free ISSS facilities because their employer failed to make mandatory social security payments, leaving them uninsured, workers must choose between costly private health care and forgoing treatment. And if the workers are financially able to opt for private treatment, they may never recover their costs – an additional deterrent to seeking private care. Employers who violate social security regulations, including by failing to make mandatory social security payments or failing to provide workers with their affiliation cards, are "responsible for the damages and injuries that the workers may suffer as a result of noncompliance."112 The responsibility falls to the workers, however, to pursue claims against their employers to recover their costs – a process that could be lengthy, arduous and, in the case of Anthony Fashions, ultimately unsuccessful if the employer cannot even be found in order to be served with process.

VI. OBSTACLES TO JUDICIAL ENFORCEMENT OF LABOR LAW

We act according to the law, although maybe against justice. It is not fair. They [the workers] lose all rights.

– Ovidio Ramírez Cuéllar, judge for the Third Labor Court of San Salvador.113

Labor court procedures, in most cases, not only last longer than Ministry of Labor administrative procedures, but they include procedural requirements that may prove prohibitively burdensome for workers seeking justice for human rights violations.114

Data is not kept on the average duration of cases before El Salvador's labor courts, but the estimates of the four labor court judges of San Salvador ranged from three to nine months.115 Cases then can be appealed to the labor courts of second instance and, ultimately, to the Supreme Court, a process which takes at least one-and-a-half years from the time of filing in most cases.116

Workers must present a minimum of two witnesses to support their cases before the labor courts, yet workers and San Salvador labor court judges explained to Human Rights Watch that finding witnesses willing and able to testify can be extremely difficult.117 A Labor Ministry official, speaking on condition of anonymity, similarly commented, "It is hard to get evidence because workers do not want to testify. They are afraid they will lose their jobs."118 There is no "whistle-blower" protection in Salvadoran labor law nor protection against dismissal for testifying against an employer. As such, a co-worker may have to choose between testifying and her job.

In at least one case, an employer even reportedly prevented an employee from testifying. According to a labor lawyer, a potential witness informed him that, in early 2002, when she arrived at the courthouse to testify on behalf of a fired co-worker, the head of human resources at the company was waiting at the courthouse for her. The head of human resources reportedly instructed her to get in a taxi or be fired and paid the taxi driver to take her far from the courthouse. The taxi left with the employee, and the former co-worker lost the case, as she was missing one of her corroborating witnesses. Afterwards, the company reportedly fired the potential witness.119

In some cases, even when workers successfully fulfill the procedural requirements and a judgment is rendered in their favor, enforcement of the judgment is elusive. For example, in the Confecciones Ninos case, described in chapter VII below, five former workers reportedly won a court judgment ordering the company to pay 100 percent of their severance pay. The employer claimed he could not pay and offered twelve machines instead. The judgment was reportedly issued in September 2002, but as of the end of July 2003, the court had not sold the machines and the workers had not received their payments.120

In other cases, workers are unable to proceed even to the preliminary, conciliation phase because the defendant employers do not appear and the labor court cannot find them to serve process. The employers close their factories and flee without fulfilling their legal obligations to their workers. For example, as discussed below, over 320 cases have been filed in San Salvador's labor courts against Anthony Fashions, which reportedly closed without paying workers severance pay, annual bonuses, and other debts. The owner has allegedly fled, and the cases are stalled and being dismissed without prejudice. Unlike civil and commercial cases,121 there is no legal provision allowing the appointment of a curator ad litem to represent absent employers in labor law proceedings. Commenting on the strict service of process requirements in labor-related cases, the judge for the Second Labor Court of San Salvador noted, "Many times [employers leave], and the workers are left without severance pay.... A labor reserve does not exist.... Labor law should contemplate a guarantee for these cases so that the workers' [rights] are not violated."122

VII. CASE STUDIES

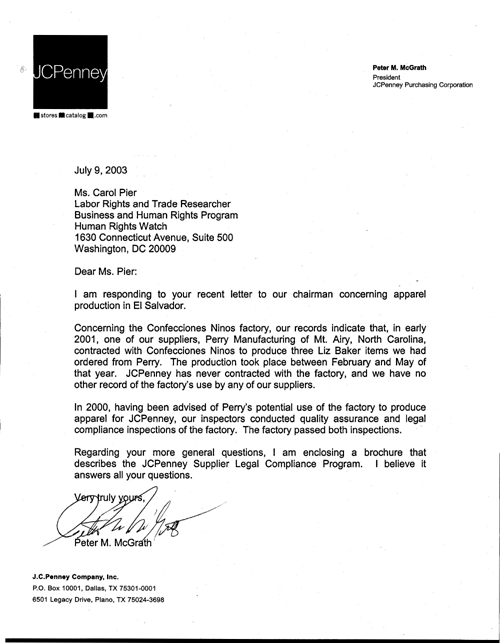

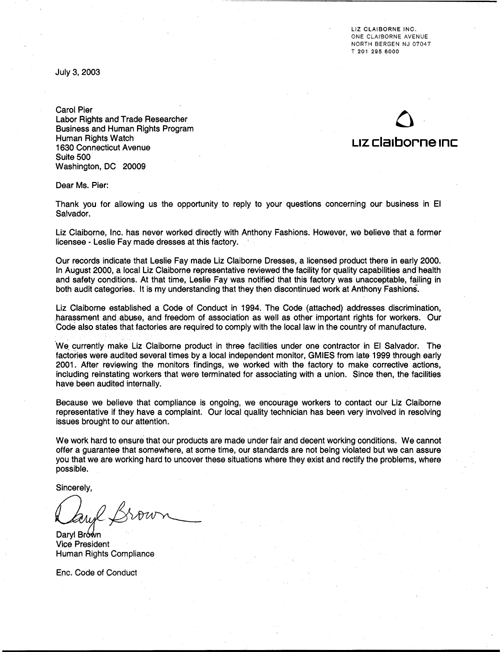

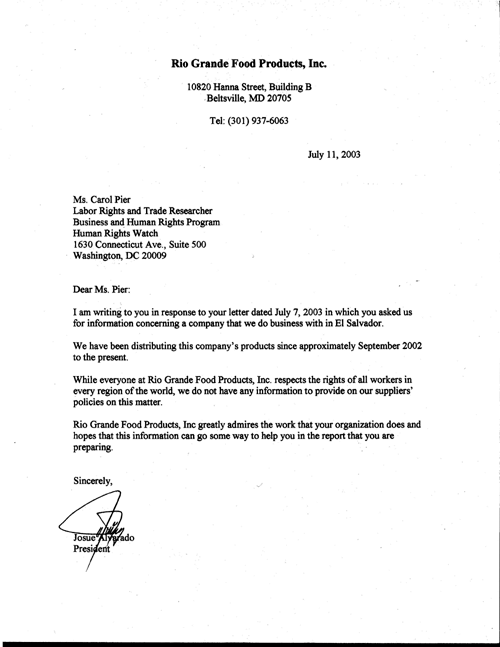

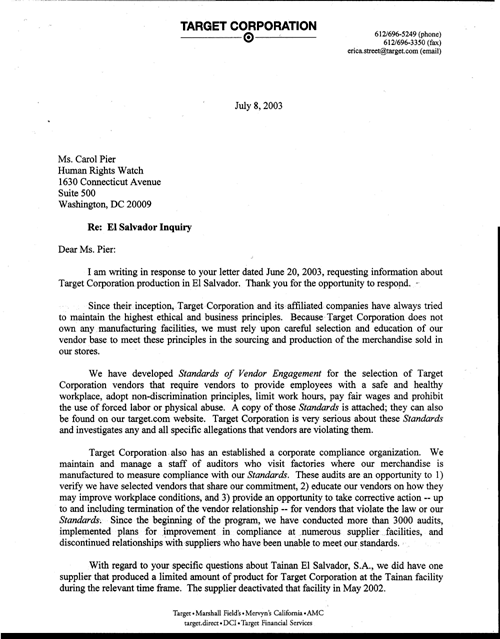

The following eight cases illustrate the violations described above. The accounts in this chapter are based on testimony from workers, union leaders and organizers, labor lawyers, non-governmental organization representatives, labor court judges, representatives from the government's Human Rights Ombudsman's Office, and current and former Ministry of Labor officials. In each case, Human Rights Watch also solicited employer responses to the allegations of workers' human rights abuses. We were not granted the meetings we requested. And, as noted below, only one of the employers responded to letters that we mailed and faxed seeking their views.123 When we were able to obtain public documents setting forth employer views, we have included them here.

Four of the eight cases profiled here are from the manufacturing sector and four from the service sector. The manufacturing cases all involve export companies, and three of the four involve textile maquilas that operated in the country's free trade zones and sent goods primarily to the United States.124 Factories like these could take advantage of commercial and tariff benefits ultimately included in CAFTA. Of the four service industry cases, two involve formerly public sector industries – electric and telecommunications – that, since 1996, have opened to private-sector participation;125 the other two involve public enterprises – the airport and social security facilities – for which privatization has been proposed by the government but forcefully opposed by workers. Human Rights Watch takes no position on privatization per se but is concerned about the alleged abuses of workers' human rights in these four cases.

The problems discussed below are representative of the many similar cases that unfold in El Salvador each year in which workers suffer labor rights violations and repeatedly and unsuccessfully seek legal redress with the Labor Ministry and/or labor courts. The cumulative effect of the multiple abuses and the government's inadequate response is that, at every turn, workers' attempts to exercise their human rights are thwarted.126

Lido, S.A. de C.V.

If you want to keep your job, you shouldn't assert your rights.... The company threw us in the street without anything and said that if we thought we had rights, we should complain to the Ministry of Labor.

– Julio Cesar Bonilla, third secretary of conflicts, Union of Lido Workers (SELSA).127

Incorporated in 1953, Lido is one of five factories founded and owned by the Molina Martínez family that produces bread and dessert products under the brand name "Lido."128 Since January 2002, Lido has reportedly violated workers' right to organize by firing union members and leaders, pressuring union members to renounce their union membership, and demanding that fired union members tender resignations and liability waivers before collecting their severance pay. The Labor Ministry's response has included, without explanation, favoring an inspection petition from the employer over one submitted by the workers, failing to investigate allegations of anti-union intimidation, and honoring illegal employer requests that payments due to workers be conditioned on workers' waiver of legal rights.

In May 2001, SELSA negotiated a collective bargaining agreement with Lido, clause 43 of which requires the employer "to review its salary tables annually, during the last two weeks of January, so that the agreed upon increase takes effect as of the following February 6." Clause 56 similarly states, "There will be an annual review of salaries."129 During that time, most Lido workers' salaries were between U.S. $233 and U.S. $295 per month, based on forty-four hour workweeks.130

When workers notified Lido in November 2001 that they would expect a salary review in 2002, Lido's managers argued that because one year had not yet passed since the agreement was reached, the company was not required to review workers' salaries.131 On November 20, 2001, workers initiated the administrative dispute resolution procedures established by the Labor Code to resolve such disagreements.132 By the end of February, direct worker-employer negotiations had failed, and, by May, Labor Ministry-facilitated mediation had also failed, as Lido maintained its refusal to negotiate salaries in 2002.133

On May 6, 2002, largely in response to the failed attempts to negotiate raises and Lido's alleged refusal to submit to Labor Ministry-facilitated arbitration, roughly 320 of the approximately 350 Lido workers engaged in a one-day work stoppage.134 Over the next three days, from May 7 through May 9, 2002, Lido barred forty-one union members from work, eleven of whom were union leaders. Thirty-six members were barred on May 7, four on May 8, and one on May 9.135 In the eyes of the law, these workers had been fired, as the Labor Code establishes that, unless a suspension or work interruption has been declared, employees are presumed dismissed if they are not allowed into the workplace during their scheduled shifts.136

The workers reportedly learned of their de facto dismissals from security guards, who informed them that they were not allowed to enter the worksite. The guards reportedly provided no justification for their actions, saying only that they "had orders."137 Nonetheless, Lido's general manager, Roberto Quiñónez, later explained to a labor inspector:

On May 6, 2002, [workers] were asked who wanted to work and who supported the action of the union [the work stoppage], the latter being those who would not be allowed to enter [the workplace].... [T]he 41 workers [can] make use of their labor rights and file corresponding actions before the competent authorities, as no possibility exists of their reinstallation.138

The ILO Committee on Freedom of Association later reviewed the case and stated that "the Committee cannot rule out the possibility that the dismissals were carried out in reprisal for the protest measure undertaken by the workers, which would be a serious violation of freedom of association."139