Somalia: Detained Children Face Abuse

| Publisher | Human Rights Watch |

| Publication Date | 21 February 2018 |

| Cite as | Human Rights Watch, Somalia: Detained Children Face Abuse, 21 February 2018, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5b39f17e7.html [accessed 22 May 2023] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Emphasize Rehabilitation, Develop Child-Specific Procedures

February 21, 2018 6:01AM EST

Somali authorities are unlawfully detaining and at times prosecuting in military courts children with alleged ties to the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab.

(Washington) – Somali authorities are unlawfully detaining and at times prosecuting in military courts children with alleged ties to the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 85-page report, "'It's Like We Are Always in a Prison': Abuses Against Boys Accused of National Security Offenses in Somalia," details due process violations and other abuses since 2015 against boys in government custody for suspected Al-Shabab-related offenses. Somalia's federal government has promised to promptly hand over captured children to the United Nations child protection agency (UNICEF) for rehabilitation. But the response of Somalia's national and regional authorities has been inconsistent and at times violated international human rights law. The government's capture of 36 children from Al-Shabab on January 18, 2018 required a week of negotiations involving the UN and child protection advocates to work out procedures for dealing with them.

"Children who suffered under Al-Shabab find themselves at risk of mistreatment and hardship in government custody," said Laetitia Bader, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. "The government's haphazard and at times outright abusive approach harms children and compounds fear and mistrust of security forces."

Human Rights Watch interviewed 80 children formerly associated with Al-Shabab, boys previously detained in intelligence custody, lawyers, child protection advocates, and government officials; conducted research into military court proceedings; and visited two prisons.

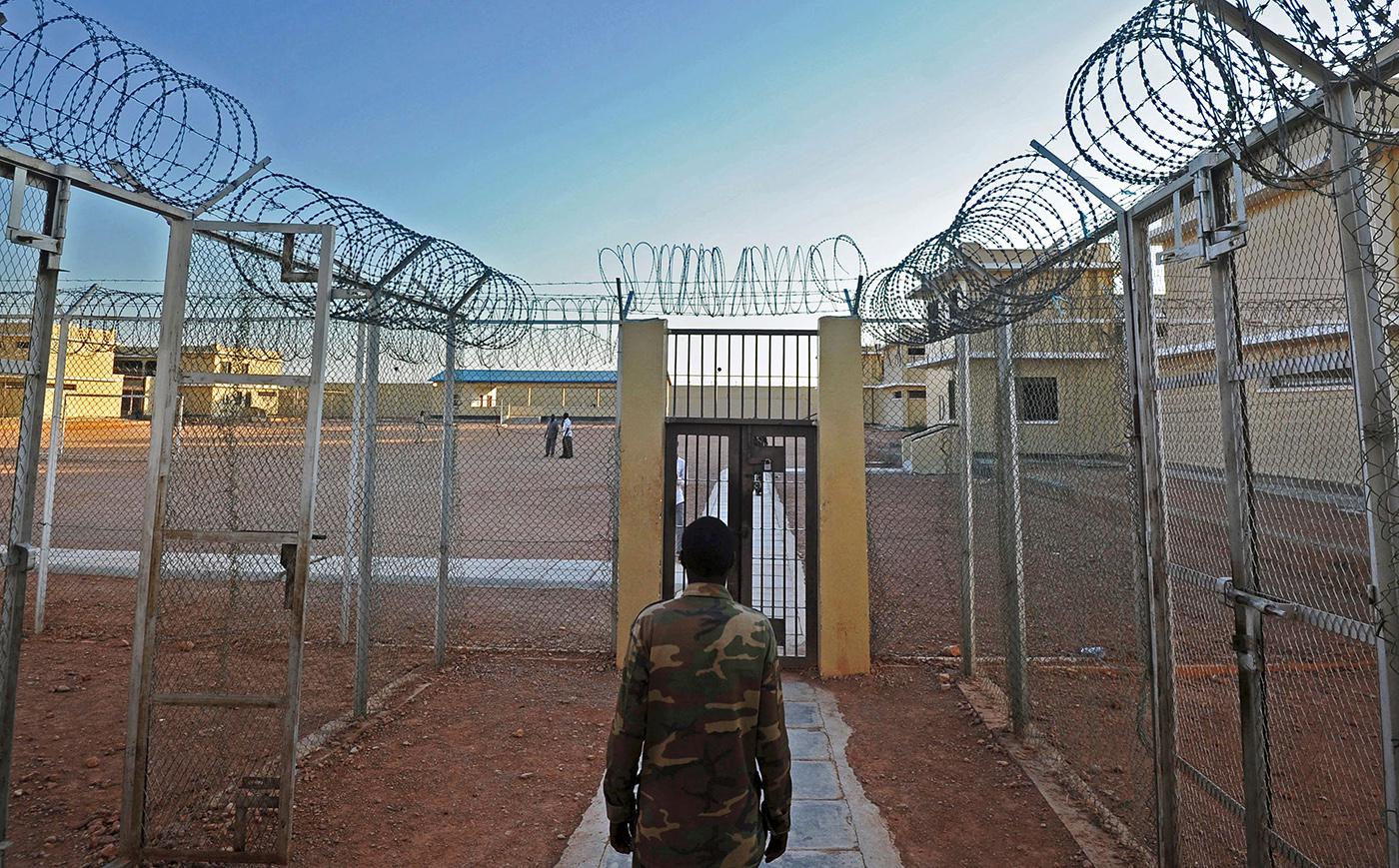

A prison warden at a prison in Garowe, Puntland state, in northeastern Somalia, December 2016. Fifty-four boys, some as young as 12, sent to fight by Al-Shabab in Puntland, spent months in this facility far from their homes. A military court sentenced 28 of the 54 boys to long prison terms, which they are now serving in a rehabilitation center in Garowe. © 2016 Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP/Getty Images

A prison warden at a prison in Garowe, Puntland state, in northeastern Somalia, December 2016. Fifty-four boys, some as young as 12, sent to fight by Al-Shabab in Puntland, spent months in this facility far from their homes. A military court sentenced 28 of the 54 boys to long prison terms, which they are now serving in a rehabilitation center in Garowe. © 2016 Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP/Getty Images

According to the UN, since 2015, authorities across Somalia have detained hundreds of boys suspected of being unlawfully associated with Al-Shabab. Somalia is obligated under international law to recognize the special situation of children, defined as anyone under 18, who have been recruited or used in armed conflict, including in terrorism-related activities, and assist their recovery and reintegration. Children who participate in armed groups can be tried for serious crimes, but legal proceedings should comply with juvenile justice standards and non-judicial measures should be considered.

Somali authorities have not handled security cases involving children in a consistent manner, Human Rights Watch found. While government officials had previously admitted to detaining boys they classified as "high risk," Human Rights Watch found that factors including socio-economic status, clan background, and external pressure may influence the outcome of a boy's case.

Boys arrested in security operations have often been held by intelligence forces, namely Somalia's National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) in Mogadishu or Puntland's Intelligence Agency (PIA) in Bosasso. Intelligence agencies decided how they categorized children, how long they kept children, and if and when they handed them over to UNICEF. Independent oversight of screening processes and custody has been severely limited.

Officials and guards have subjected children to coercive treatment and interrogations including cutting them off from their relatives and legal counsel, threatening them, and on occasion beating and torturing them, primarily to obtain confessions or as punishment for speaking out or disorder in the cells. A 16-year-old held for months in a NISA facility in 2016 said: "They would take me out of my cell at night and pressure me to confess. One night, they beat me hard with something that felt like a metal stick. I was bleeding for two weeks, but no one treated me."

Children also described being held with adult detainees in dire conditions for days without seeing family. A 15-year-old detained in a mass sweep in 2017 and held by NISA for several weeks said: "I couldn't sleep at night as there was no space and I suffered from excruciating headaches, but received no medication."

While the criminal prosecution of children is not common in Somalia, the authorities make use of an outdated legal system to try children in military courts, primarily as adults, for security crimes, including solely for Al-Shabab membership, Human Rights Watch found. Since 2016, over two dozen children have been tried in military courts in Puntland alone. Children face proceedings that fail to meet basic juvenile justice standards with limited ability to prepare a defense and in which coercive confessions have been admitted as evidence.

Boys who were first used by Al-Shabab and then detained by government security forces said that felt doubly trapped and victimized. "I feel afraid and let down," said a 15-year old whom Al-Shabab abducted and then sent to fight in Puntland in March 2016, only to be captured and sentenced by a military court to 10 years in prison. "Al-Shabab forced me into this, and then the government gives me this long sentence."

While federal and regional authorities have handed over 250 children to UNICEF for rehabilitation since 2015, this has largely been the result of sustained advocacy and often after children have spent considerable time in detention.

Somali authorities should end arbitrary detention of children, allow for independent monitoring of children in custody, and ensure access to relatives and legal counsel. If children are to be prosecuted for other serious offenses, they should be tried in civilian courts that guarantee basic juvenile justice protections, and any punishment should consider alternatives to detention and prioritize the child's reintegration into society.

Somalia's international partners should press for civilian oversight of cases involving children, seek independent monitoring of all detention facilities, and call for the credible investigation of abuses against children, including by intelligence officers, Human Rights Watch said.

"The Somali government should treat children as victims of the conflict, and ensure that children, regardless of the crimes they may have committed, are accorded the basic protection due to all children," Bader said. "Authorities across the country should improve supervision of children in detention and prioritize rehabilitation in addressing their cases. International partners should help bolster child-specific judicial and other procedures."

Link to original story on HRW website