By UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and UNHCR

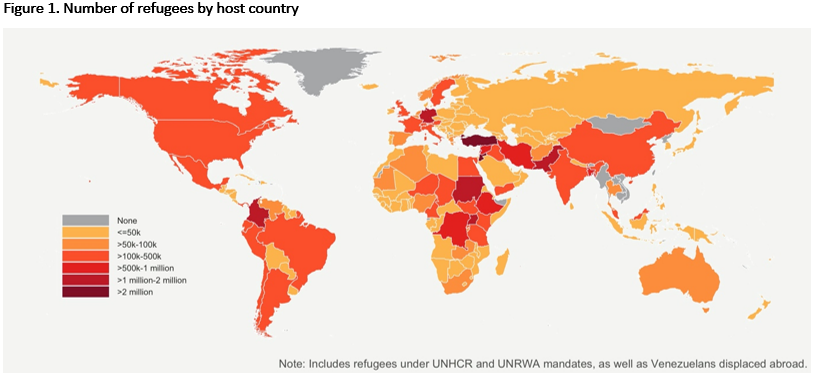

The achievement of UN SDG 4 on quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all is under threat. The last three decades have seen a spike in the number of refugees who have been forcibly displaced from their homes (Figure 1). With a global rise in protracted crises, refugees face crises of protection, access to basic services and relentless disruption to their lives. Among them, refugee children, representing 4 in 10 refugees, face significant challenges in accessing education, with many at risk of not enrolling in school or being guaranteed any continuity in their learning.

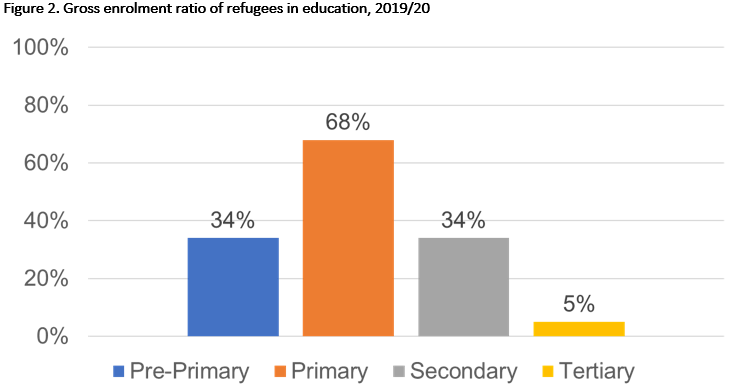

Recent data representing more than half of school-aged refugee children and Venezuelans displaced above show that nearly half are out of school (Figure 2). But the reality is somewhat masked by under-representation of refugee children in official data. Those who do enroll in schools may not be counted in the data either because their learning facilities (e.g., temporary learning centres in refugee settlements) are excluded from the formal education system where data collection takes place; or due to the absence of data disaggregated by protection status when they are in formal schools. Both factors lead to refugee children being uncounted and invisible in the data, and consequently having their distinct educational needs unheard and unmet.

What data are currently available on refugee education?

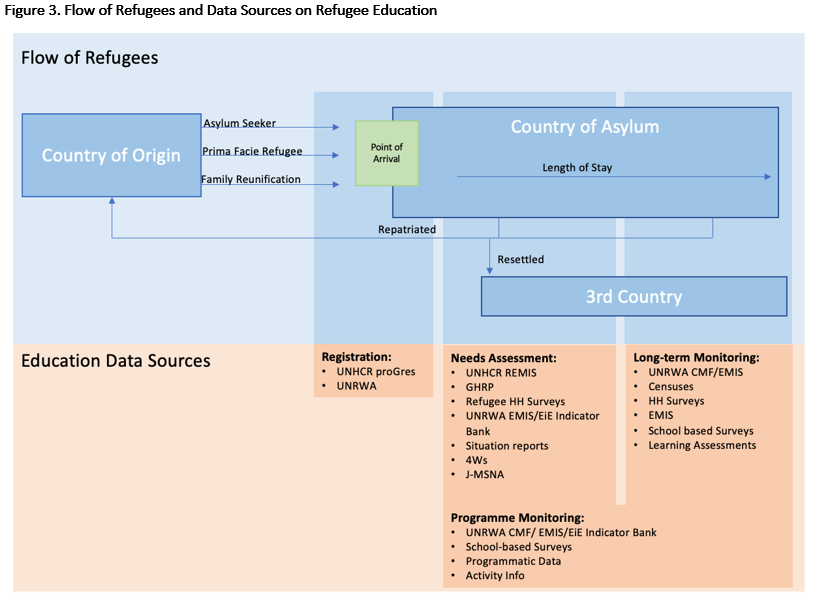

A new joint report by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and UNHCR highlights the plight of refugee children globally and acknowledges their invisibility and under-representation in education data. The report undertakes a comprehensive review of data sources to uncover the reasons for the shortage of data on refugee education and further suggests ways to address the shortage. Sources studied range from the UN registration and monitoring data (e.g., UNHCR’s Profile Global Registration System (proGres) and United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East’s EiE Indicator Bank) to household surveys and administrative data (Education Management Information Systems, EMIS) located across different stages of refugee movement (from country of origin to host country, including repatriation, resettlement, and local integration) and phases of the refugee response programming cycle (see Figure 3 for a summary of these data sources).

What are the main issues and how do we move forward?

Refugee education data currently fails to adequately capture the range of education service delivery for refugee children. Collecting refugee education data is a complex undertaking and the UIS-UNHCR report identifies three main challenges:

- Absence of disaggregation by refugee status (or adequate proxies) in contexts where refugee children attend government schools and are part of administrative surveys (such as EMIS). This is linked to two other challenges: the identification of refugees, where distinguishing between refugees and non-refugees – especially when using proxies such as nationality or native language – can prove difficult; and the protection risks associated with identifying refugee children and disaggregating data by refugee status, particularly in contexts where refugees may be under threat, highlighting that data confidentiality and protection has to be prioritized, and that data proxies must be chosen with care.

- Overly narrow emphasis on access to education which excludes other education dimensions, such as learning and protection suggesting that even if refugee children are attending school, we know very little about their education experiences.

- Fragmented and weak coordination on refugee education data risks duplication of data, lack of data sharing agreements, and an unclear pathway towards ensuring refugee access to quality and safe education.

Recommendations and opportunities

Understanding the needs of refugees requires disaggregated education data and leveraging existing data collection efforts and procedures. This means prioritizing the safe identification of refugees within existing data collection tools such as EMIS; introducing questions on refugee status in line with recent recommendations by the Expert Group on Refugee and IDP Statistics or using nationality as a proxy where it is not feasible or safe to ask about refugee status. This is urgently needed in contexts where refugees are included in national education systems yet are not separately identified in data systems, limiting the possibility of addressing their unique learning needs such as on language acquisition, performance, transition, and continuity into higher education and learning. Further disaggregating refugee education data by age, gender and disability status can further promote understanding of the specific needs and nuances of access, learning and safety of socially diverse refugee populations.

Using this identification and disaggregation approach is critical to developing better responses to educational needs for refugee children. The approach enables UNHCR, its partners and other actors to move beyond measuring access to education to measuring learning (e.g., national examinations and international assessments), quality of school environments (e.g., textbooks and teacher training as captured in EMIS), as well as protection and safety (e.g., peer violence and corporal punishment as captured in e.g., PISA, TIMSS, TERCE).

Finally, encouraging greater coordination on refugee education data collection, management and sharing is critical to avoid duplication. Existing mechanisms, such as the INEE Data Reference Group on Education in Emergencies (EiE) co-chaired by the UIS and ECW, can serve as examples of platforms that aim to coordinate and galvanize efforts from diverse stakeholders to improve, standardize and share existing data and knowledge on EiE, with the need for greater data coordination at the national and regional levels to be addressed. These practices can contribute to ensuring that the needs of refugee children are included in education planning around the world. In this vein, creating a clearing committee under existing institutional mechanisms, such as for example UNCHR, to establish a standard definition, methodology, approach to identifying refugees (and defining relevant education variables) in EMIS, HH surveys and large-scale learning assessments would be a big step in ensuring data quality.