Meet Kykeo

The ‘Karate Kid’ who is ‘more Argentine than dulce de leche’ By Analia Kim and Jenny Barchfield

Buenos Aires, Argentina

8 June 2022

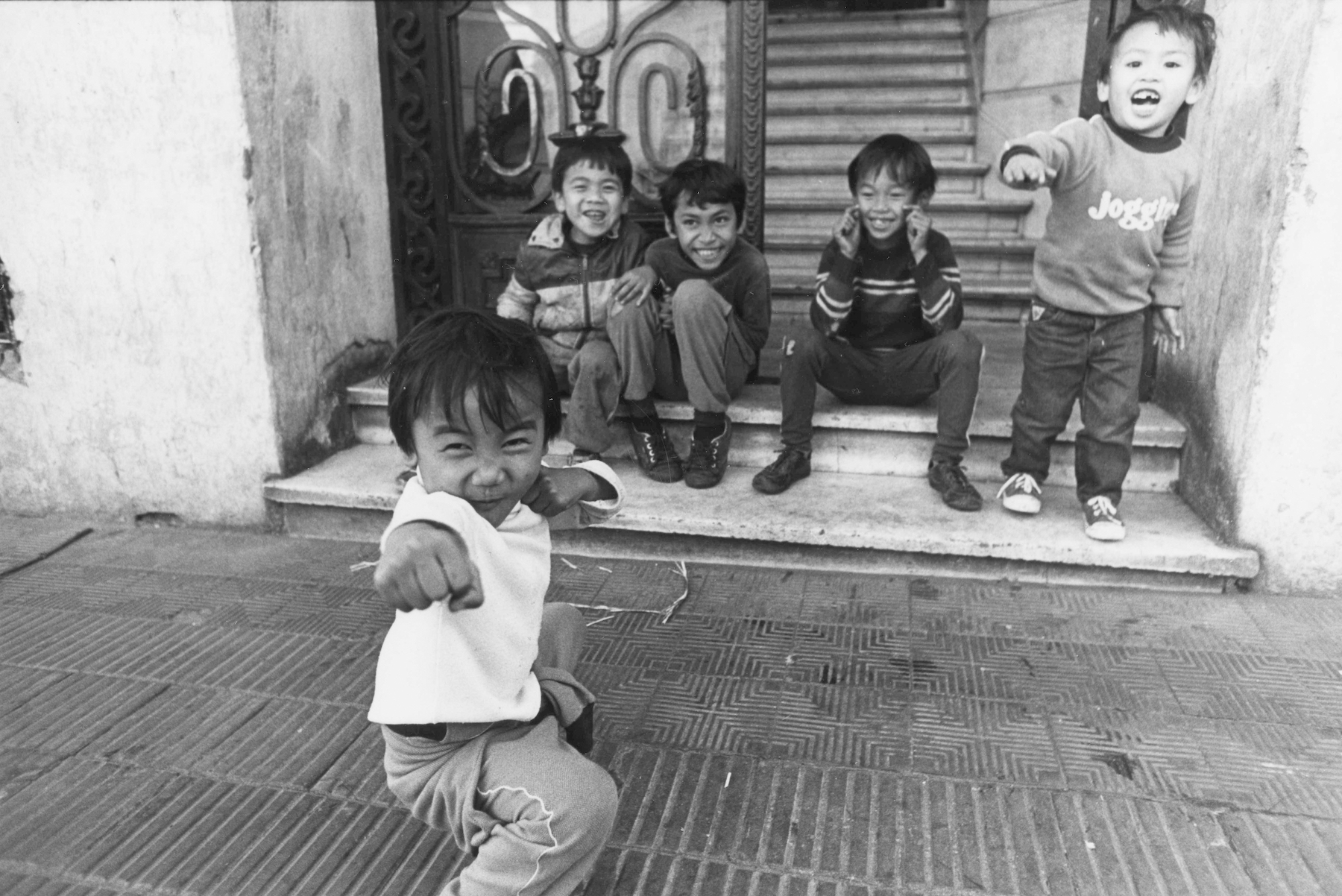

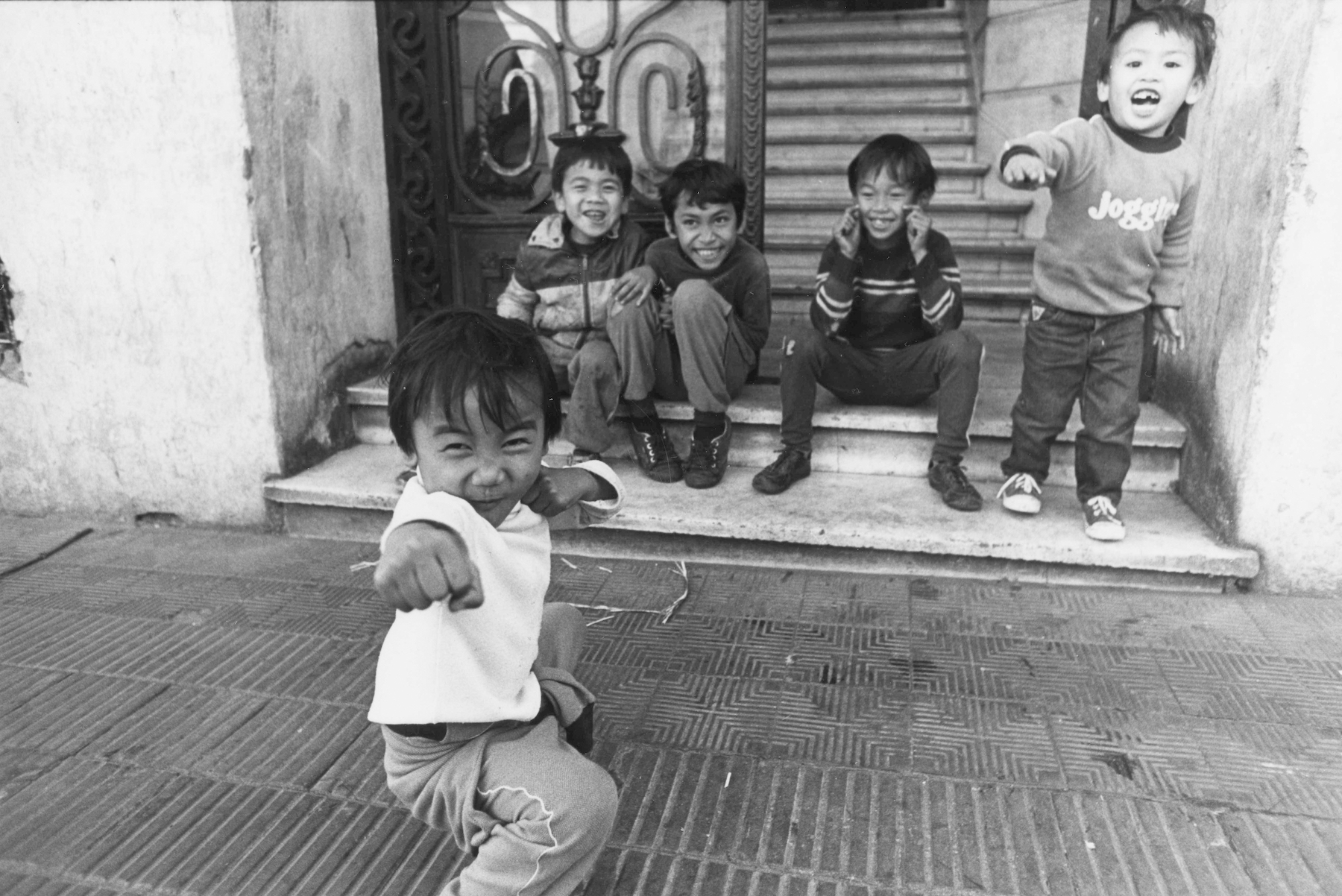

Kykeo Kabsuvan, a young refugee from Laos, poses for a photo with his brother and friends in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1983. ©UNHCR/Alejandro Cherep

Meet Kykeo

The ‘Karate Kid’ who is ‘more Argentine than dulce de leche’

By Analia Kim and Jenny Barchfield

Buenos Aires, Argentina

8 June 2022

Kykeo Kabsuvan, a young refugee from Laos, poses for a photo with his brother and friends in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1983. ©UNHCR/Alejandro Cherep

Almost 40 years ago, a photojournalist snapped a picture of Kykeo Kabsuvan, a young refugee from Laos who had been resettled to Argentina. Now a karate teacher, football fan and avid mate drinker, Kykeo is a model of integration.

Thirty-nine years had passed, but for Kykeo Kabsuvan, his brother and friends, it was as if time had stood still. Now in their forties, the childhood friends came together from across Argentina to recreate a photo that was taken in 1983, when they were boys aged 4-10.

None had any recollection of the day the photo was taken, but they all slipped seamlessly into their roles. Kykeo’s older brother, Dang, and two friends assumed their positions on the stoop of the Buenos Aires hotel that they all called home after their families were resettled from Laos to Argentina in the late 1970s. Meanwhile, in the foreground, Kykeo expertly struck a karate pose, his bright, impish grin undimmed by the intervening decades.

“I didn’t know what I was doing,” said Kykeo, 43, who now, as fate would have it, is a professional karate instructor. “We liked to play fight, but we had no idea that was a karate move. … I thought it was so funny when I saw it [the photo].”

“We had no idea that was a karate move.”

While karate appears to have come naturally to Kykeo, as a boy he built on that innate skill with lessons starting at around age nine. By his early teens, he had obtained his black belt, and his coaches saw him as a strong candidate for Argentina’s national selection.

But Kykeo’s Olympic dreams were dashed when the young athlete learned that as a refugee, he was ineligible to represent Argentina. In fact, it would be several more years until he could begin the process of being naturalized in the country he had called home since infancy.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

“I didn’t know what I was doing,” said Kykeo, 43, who now, as fate would have it, is a professional karate instructor. “We liked to play fight, but we had no idea that was a karate move. … I thought it was so funny when I saw it [the photo].”

“We had no idea that was a karate move.”

While karate appears to have come naturally to Kykeo, as a boy he built on that innate skill with lessons starting at around age nine. By his early teens, he had obtained his black belt, and his coaches saw him as a strong candidate for Argentina’s national selection.

But Kykeo’s Olympic dreams were dashed when the young athlete learned that as a refugee, he was ineligible to represent Argentina. In fact, it would be several more years until he could begin the process of being naturalized in the country he had called home since infancy.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Kykeo was just nine months old when he and his family were airlifted from a refugee camp in Thailand housing Laotians. The year was 1979, amid the upheavals that would lead more than 3 million people to flee the countries that made up the former French colony of Indochina: Cambodia, Laos and Viet Nam.

While the majority of those who fled ended up in the United States, France and Canada, the Kabsuvans were among 293 Laotian families to be resettled in Argentina, according to Prof. Chia Youyee Vang, a scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

“They had no idea what Argentina would be like… They had no idea where they were going, but they trusted that ‘here is someone providing refuge to me and my family, so I’m going to go.’ But they had no frame of reference for what was in store” for them in Argentina, said Chia, who has conducted extensive research on the Laotian diaspora and played a crucial role in identifying Kykeo and the others in the photo.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Kykeo was just nine months old when he and his family were airlifted from a refugee camp in Thailand housing Laotians. The year was 1979, amid the upheavals that would lead more than 3 million people to flee the countries that made up the former French colony of Indochina: Cambodia, Laos and Viet Nam.

While the majority of those who fled ended up in the United States, France and Canada, the Kabsuvans were among 293 Laotian families to be resettled in Argentina, according to Prof. Chia Youyee Vang, a scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

“They had no idea what Argentina would be like… They had no idea where they were going, but they trusted that ‘here is someone providing refuge to me and my family, so I’m going to go.’ But they had no frame of reference for what was in store” for them in Argentina, said Chia, who has conducted extensive research on the Laotian diaspora and played a crucial role in identifying Kykeo and the others in the photo.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Shot by Alejandro Cherep, an Argentine photojournalist working for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, the black-and-white image was selected out of agency’s extensive photo archive to be colourized as part of an ongoing project called “The Colour of Flight”. UNHCR brought Kykeo, his brother and the others to Buenos Aires in November 2021 to recreate the photo.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Shot by Alejandro Cherep, an Argentine photojournalist working for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, the black-and-white image was selected out of agency’s extensive photo archive to be colourized as part of an ongoing project called “The Colour of Flight”. UNHCR brought Kykeo, his brother and the others to Buenos Aires in November 2021 to recreate the photo.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

After their time at the Estrella Hotel, where the photo was shot, many of the resettled Laotian families moved to Rosario, Argentina’s third most populous city, a few hours northwest of the capital. Even today, the Laotian community in Rosario remains strong.

Kykeo’s parents, however, went their own way, eventually buying a house in San Nicolás de los Arroyos, a small provincial city where the Kabsuvans were among the sole residents of Asian descent. As a kid, looking different from his classmates weighed heavily on Kykeo.

“It was uncomfortable … the jokes about eating rice every day,” he said, adding, “We always felt different from most Argentine people.”

Things got harder for Kykeo and Dang after their parents separated and their father suffered a devastating stroke while still in his 30s. With their dad partially paralyzed and their mother working long hours selling clothes door-to-door, the boys were sent to live in a group home with Christian missionaries for a time.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Things got harder for Kykeo and Dang after their parents separated and their father suffered a devastating stroke while still in his 30s. With their dad partially paralyzed and their mother working long hours selling clothes door-to-door, the boys were sent to live in a group home with Christian missionaries for a time.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

It was shortly after their mother was able to send for them to rejoin her that the boys began karate lessons. The karate coaches ended up taking on an almost fatherly role for Kykeo, whose own father never recovered from the stroke and required extensive care until his death two years ago.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

It was shortly after their mother was able to send for them to rejoin her that the boys began karate lessons. The karate coaches ended up taking on an almost fatherly role for Kykeo, whose own father never recovered from the stroke and required extensive care until his death two years ago.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

“I couldn’t ask for advice from my dad, so whenever I had anything I wanted to know, I would always ask my coach,” said Kykeo, adding that above and beyond the physical challenges of karate, he always appreciated the moral rigour of the sport. “I liked the lessons and values that karate gives you as a person.”

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

“I couldn’t ask for advice from my dad, so whenever I had anything I wanted to know, I would always ask my coach,” said Kykeo. Above and beyond the physical challenges of karate, he added, he always appreciated the moral rigor of the sport. “I liked the lessons and values that karate gives you as a person.”

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

For Kykeo, then still a teenager, the news of his ineligibility to compete for a spot on Argentina’s national karate team stung. Argentina was, after all, the only country he had ever really known. Kykeo had always enthusiastically embraced all things Argentine – from soccer to mate, the bitter herbal tea stimulant that he and many of his fellow Argentines nurse all day.

“I may have Asian features,” said Kykeo, with a flash of his high-wattage smile. “But I’m more Argentine than dulce de leche,” he said, referring to the unctuous caramel that is an Argentine national obsession.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

For Kykeo, then still a teenager, the news of his ineligibility to compete for a spot on Argentina’s national karate team stung. Argentina was, after all, the only country he had ever really known. Kykeo had always enthusiastically embraced all things Argentine – from soccer to mate, the bitter herbal tea stimulant that he and many of his fellow Argentines nurse all day.

“I may have Asian features,” said Kykeo, with a flash of his high-wattage smile. “But I’m more Argentine than dulce de leche,” he said, referring to the unctuous caramel that is an Argentine national obsession.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Unable to take part in the most important national tournaments, young Kykeo drifted away from karate, eventually dropping out of high school and taking a job in a clothing factory in Buenos Aires. He had three daughters before separating from the girls’ mother and moving back to San Nicolás a few years ago.

Kykeo has come full circle. He and his new partner, Giovana Monzón, have moved back into the Kabsuvan family home with Brisa and Elías, her two children from a former marriage. The pair are expecting a child, and Kykeo dreams of turning what used to be the home’s garage into a small gym.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Unable to take part in the most important national tournaments, young Kykeo drifted away from karate, eventually dropping out of high school and taking a job in a clothing factory in Buenos Aires. He had three daughters before separating from the girls’ mother and moving back to San Nicolás a few years ago.

Kykeo has come full circle. He and his new partner, Giovana Monzón, have moved back into the Kabsuvan family home with Brisa and Elías, her two children from a former marriage. The pair are expecting a child, and Kykeo dreams of turning what used to be the home’s garage into a small gym.

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Gustavo Torres, who is among Kykeo’s most assiduous karate students, says he admires his friend and teacher’s devotion to the sport.

“His dedication and the passion he feels for teaching really come through,” said Gustavo, whose friendship with Kykeo dates back decades, to when both were just beginning karate lessons. “He’s just the right person for the job.”

In the gym he hopes to open, Kykeo plans on offering CrossFit and other fitness classes. That’s in addition, of course, to karate – the sport he credits with having given him an unwavering moral compass that has allowed him to cope with the ups and downs of a life marked by change and loss.

Karate “teaches a lot of very important lessons that go beyond just how to hit,” he said, adding, “respect – it teaches you respect.”

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Gustavo Torres, who is among Kykeo’s most assiduous karate students, says he admires his friend and teacher’s devotion to the sport.

“His dedication and the passion he feels for teaching really come through,” said Gustavo, whose friendship with Kykeo dates back decades, to when both were just beginning karate lessons. “He’s just the right person for the job.”

In the gym he hopes to open, Kykeo plans on offering CrossFit and other fitness classes. That’s in addition, of course, to karate – the sport he credits with having given him an unwavering moral compass that has allowed him to cope with the ups and downs of a life marked by change and loss.

Karate “teaches a lot of very important lessons that go beyond just how to hit,” he said, adding, “respect – it teaches you respect.”

Photo ©UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso