On the frontlines of the global displacement crisis

2021: forced displacement in pictures.On the frontlines of the global displacement crisis

2021: forced displacement in pictures.A family rests in the Mexican city of Rio Frio de Juarezas as they journey towards Mexico City, 11 December ©REUTERS/Luis Cortes

When an emergency is declared, UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, is on the ground to ensure that people forced to flee find safety and assistance – whether in their own country or another. The proliferation of new crises in 2021, combined with the lack of solutions to resolve lingering ones, has tested our ability to respond like never before.

Conflicts, old and new, along with the increasingly disastrous impacts of climate change, drove a devastating rise in the number of forcibly displaced people this year. From Afghanistan to Ethiopia, people were uprooted by violence, persecution and human rights violations. Many of them faced additional hardships resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, extreme weather, and increasingly restrictive asylum laws and border policies.

In a year that marked the 70th anniversary of the landmark 1951 Refugee Convention, its principles of international cooperation to protect and preserve the rights of people forced to flee have never been more relevant, nor under greater threat.

UNHCR staff and partners were on the frontlines of new emergencies and ongoing crises in 135 countries around the world this year, but there were a number of situations that stood out due to their scale and complexity, as well as some memorable moments that showcased the talents and resilience of people forced to flee.

When an emergency is declared, UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, is on the ground to ensure that people forced to flee find safety and assistance – whether in their own country or another. The proliferation of new crises in 2021, combined with the lack of solutions to resolve lingering ones, has tested our ability to respond like never before.

Conflicts, old and new, along with the increasingly disastrous impacts of climate change, drove a devastating rise in the number of forcibly displaced people this year. From Afghanistan to Ethiopia, people were uprooted by violence, persecution and human rights violations. Many of them faced additional hardships resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, extreme weather, and increasingly restrictive asylum laws and border policies.

In a year that marked the 70th anniversary of the landmark 1951 Refugee Convention, its principles of international cooperation to protect and preserve the rights of people forced to flee have never been more relevant, nor under greater threat.

UNHCR staff and partners were on the frontlines of new emergencies and ongoing crises in 135 countries around the world this year, but there were a number of situations that stood out due to their scale and complexity, as well as some memorable moments that showcased the talents and resilience of people forced to flee.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan was grappling with multiple crises even before the withdrawal of foreign troops triggered an escalation in fighting between the Taliban and former government forces. By the time the Taliban took power in August, some half a million people had been newly displaced. The suspension of foreign aid and the freezing of government assets, combined with a prolonged drought, plunged the country into a severe economic crisis that by December was causing widespread hunger. Some 9 million Afghans are now at risk of famine.

Afghans queue to enter Pakistan at the Spin Boldak border crossing on 12 December ©UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

Afghanistan

Afghanistan was grappling with multiple crises even before the withdrawal of foreign troops triggered an escalation in fighting between the Taliban and former government forces. By the time the Taliban took power in August, some half a million people had been newly displaced. The suspension of foreign aid and the freezing of government assets, combined with a prolonged drought, plunged the country into a severe economic crisis that by December was causing widespread hunger. Some 9 million Afghans are now at risk of famine.

Afghans queue to enter Pakistan at the Spin Boldak border crossing on 12 December ©UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

Ethiopia

The conflict that started in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in November 2020 escalated in 2021, spreading to neighbouring Amhara and Afar regions in October. Thousands of Eritrean refugees in two camps in Tigray were caught up in the conflict in July and forced to flee. Over 3 million people have now been internally displaced and millions more are in urgent need of food and other aid, which humanitarian agencies have struggled to deliver due to lack of access and the volatile security situation.

Eritrean refugees wait to receive humanitarian aid at Mai Aini refugee camp in Ethiopia’s Tigray region © UNHCR/Petterik Wiggers.

Ethiopia

The conflict that started in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in November 2020 escalated in 2021, spreading to neighbouring Amhara and Afar regions in October. Thousands of Eritrean refugees in two camps in Tigray were caught up in the conflict in July and forced to flee. Over 3 million people have now been internally displaced and millions more are in urgent need of food and other aid, which humanitarian agencies have struggled to deliver due to lack of access and the volatile security situation.

Eritrean refugees wait to receive humanitarian aid at Mai Aini refugee camp in Ethiopia’s Tigray region © UNHCR/Petterik Wiggers.

Tokyo Games

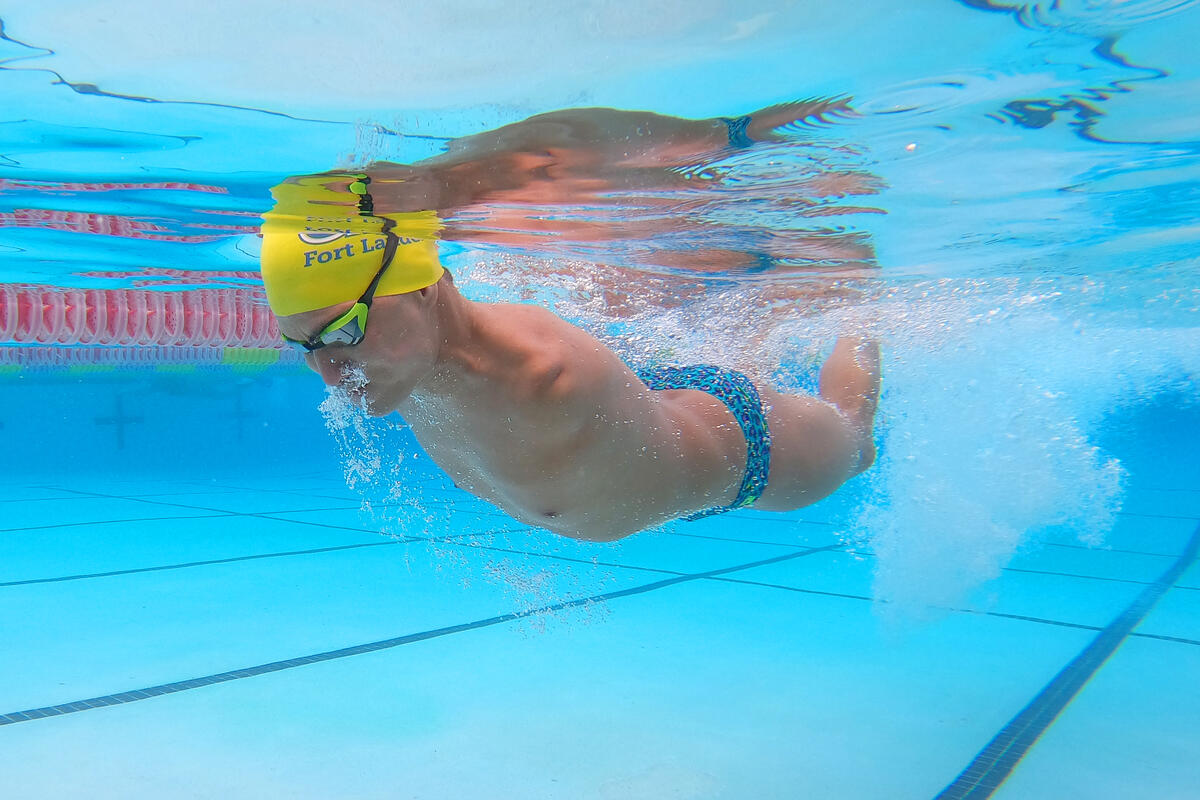

At this year’s Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games – delayed by a year due to COVID-19 – refugee athletes captured the global imagination with their displays of courage and determination. Despite missing out on the medals, only narrowly in some cases, the 29-member Refugee Olympic Team and 6-member Refugee Paralympic Team overcame greater obstacles than most to claim their place on the world’s biggest sporting stage. In the process they created some of the most memorable moments of the Games and sent a powerful message of hope to the world.

Abbas Karimi, an Afghan refugee swimmer who was born without arms, trains in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, ahead of the Paralympic Games in Tokyo © Getty Images / Michael Reaves

Tokyo Games

At this year’s Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games – delayed by a year due to COVID-19 – refugee athletes captured the global imagination with their displays of courage and determination. Despite missing out on the medals, only narrowly in some cases, the 29-member Refugee Olympic Team and 6-member Refugee Paralympic Team overcame greater obstacles than most to claim their place on the world’s biggest sporting stage. In the process they created some of the most memorable moments of the Games and sent a powerful message of hope to the world.

Abbas Karimi, an Afghan refugee swimmer who was born without arms, trains in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, ahead of the Paralympic Games in Tokyo © Getty Images / Michael Reaves

Sea crossings

From the Mediterranean to the Andaman Sea and the English Channel, refugees and migrants continued to lose their lives attempting dangerous sea crossings in 2021. By late November, nearly 1,600 had perished in the Mediterranean alone, most of them during attempts to cross from Libya and Tunisia to Italy. NGO rescue vessels brought many to safety while others were returned to Libya. UNHCR called for enhanced State-led search-and-rescue operations.

A rescue team from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) evacuates people from an inflatable boat in the Libyan search-and-rescue zone of the Mediterranean on 23 October © Espen Rasmussen.

Sea crossings

From the Mediterranean to the Andaman Sea and the English Channel, refugees and migrants continued to lose their lives attempting dangerous sea crossings in 2021. By late November, nearly 1,600 had perished in the Mediterranean alone, most of them during attempts to cross from Libya and Tunisia to Italy. NGO rescue vessels brought many to safety while others were returned to Libya. UNHCR called for enhanced State-led search-and-rescue operations.

A rescue team from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) evacuates people from an inflatable boat in the Libyan search-and-rescue zone of the Mediterranean on 23 October © Espen Rasmussen.

Bangladesh

Four years after fleeing to Bangladesh from Myanmar, Rohingya refugees faced one of their most challenging years yet. The continuing COVID-19 pandemic brought further movement restrictions in the camps in Cox’s Bazar while a massive fire in March reduced nearly 10,000 shelters to ashes and killed 11 refugees. A particularly severe monsoon season soon after triggered extreme flooding, forcing some 24,000 refugees to abandon their homes and underscoring the threat posed by more frequent and intense cyclones as a result of climate change.

Rohingya refugee children play after a heavy monsoon downpour in Nayapara refugee camp in Teknaf, eastern Bangladesh © UNHCR/Amos Holder

Bangladesh

Four years after fleeing to Bangladesh from Myanmar, Rohingya refugees faced one of their most challenging years yet. The continuing COVID-19 pandemic brought further movement restrictions in the camps in Cox’s Bazar while a massive fire in March reduced nearly 10,000 shelters to ashes and killed 11 refugees. A particularly severe monsoon season soon after triggered extreme flooding, forcing some 24,000 refugees to abandon their homes and underscoring the threat posed by more frequent and intense cyclones as a result of climate change.

Rohingya refugee children play after a heavy monsoon downpour in Nayapara refugee camp in Teknaf, eastern Bangladesh © UNHCR/Amos Holder

Belarus border

Thousands of refugees and migrants have entered Belarus since the summer, attempting to cross into Poland, Lithuania and Latvia. Many have then become stranded in remote forest areas as border forces repeatedly push them back. Some 13 deaths have been recorded due to the freezing conditions. Belarusian authorities moved about 2,000 people to a warehouse facility in November, but an unknown number remain in the forest on either side of the border, largely cut off from assistance and exposed to harsh winter conditions and the threat of hypothermia.

A child at a makeshift camp established by refugees and migrants near the Bruzgi-Kuznica checkpoint on the Belarusian-Polish border on 18 November © REUTERS/Kacper Pempel

Belarus border

Thousands of refugees and migrants have entered Belarus since the summer, attempting to cross into Poland, Lithuania and Latvia. Many have then become stranded in remote forest areas as border forces repeatedly push them back. Some 13 deaths have been recorded due to the freezing conditions. Belarusian authorities moved about 2,000 people to a warehouse facility in November, but an unknown number remain in the forest on either side of the border, largely cut off from assistance and exposed to harsh winter conditions and the threat of hypothermia.

A child at a makeshift camp established by refugees and migrants near the Bruzgi-Kuznica checkpoint on the Belarusian-Polish border on 18 November © REUTERS/Kacper Pempel

Statelessness

While 4.2 million people around the world are known to be stateless the true number is likely to be much higher. Without citizenship, they often lack the protection of any government. As a result, stateless people can fall through the cracks during situations of conflict and displacement and find themselves excluded from legal employment and government services including the ongoing COVID-19 reponse. However, more and more countries are joining the UN’s 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, which marked its 60th anniversary this year. Iceland and Togo’s accession in 2021 brought the total number of signatory countries to 77.

Liyatu, a traditional birth attendant at Durumi camp for displaced people in Abuja, Nigeria, is happy that the babies she has delivered now have birth certificates, reducing their risk of statelessness ©UNHCR/Gabriel Adeyemo

Statelessness

While 4.2 million people around the world are known to be stateless the true number is likely to be much higher. Without citizenship, they often lack the protection of any government. As a result, stateless people can fall through the cracks during situations of conflict and displacement and find themselves excluded from legal employment and government services including the ongoing COVID-19 reponse. However, more and more countries are joining the UN’s 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, which marked its 60th anniversary this year. Iceland and Togo’s accession in 2021 brought the total number of signatory countries to 77.

Liyatu, a traditional birth attendant at Durumi camp for displaced people in Abuja, Nigeria, is happy that the babies she has delivered now have birth certificates, reducing their risk of statelessness ©UNHCR/Gabriel Adeyemo

South Sudan flooding

Across South Sudan, over 835,000 people have been affected by flooding which has hit eight out of 10 states since May, submerging villages and forcing people to flee to higher ground. Many of those affected were still struggling to recover from two previous years of severe flooding, on top of conflict, COVID-19 and widespread hunger. Increasingly unpredictable rains in South Sudan and elsewhere in East Africa have been widely attributed to the effects of the climate emergency.

A woman wades through floodwaters near Bentiu in South Sudan’s Rubkona county to collect firewood © Njiiri Karago/MSF

South Sudan flooding

Across South Sudan, over 835,000 people have been affected by flooding which has hit eight out of 10 states since May, submerging villages and forcing people to flee to higher ground. Many of those affected were still struggling to recover from two previous years of severe flooding, on top of conflict, COVID-19 and widespread hunger. Increasingly unpredictable rains in South Sudan and elsewhere in East Africa have been widely attributed to the effects of the climate emergency.

A woman wades through floodwaters near Bentiu in South Sudan’s Rubkona county to collect firewood © Njiiri Karago/MSF

Yemen

After more than six years of conflict, survival is a daily struggle for millions of displaced Yemenis. This year, the conflict has shifted to Marib governorate – a region that was long a haven for people who had fled fighting in other parts of the country. As the frontlines move ever closer to densely populated areas, including camps for internally displaced people, tens of thousands of people have had to flee. For many, it was their third or fourth displacement since the war began.

One of the makeshift shelters for internally displacement people in Al-Rawdah camp in Marib city © UNHCR/YPN/Jihad al-Nahari

Yemen

After more than six years of conflict, survival is a daily struggle for millions of displaced Yemenis. This year, the conflict has shifted to Marib governorate – a region that was long a haven for people who had fled fighting in other parts of the country. As the frontlines move ever closer to densely populated areas, including camps for internally displaced people, tens of thousands of people have had to flee. For many, it was their third or fourth displacement since the war began.

One of the makeshift shelters for internally displacement people in Al-Rawdah camp in Marib city © UNHCR/YPN/Jihad al-Nahari

The Central Sahel

Extremist groups continued to drive displacement in Africa’s volatile Central Sahel region, which includes Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. In Burkina Faso alone, more than 1.4 million people have been internally displaced over the past two years, and attacks on civilians and security forces have continued throughout the year. Mali and Niger also experienced a sharp rise in violence and displacement in 2021.

Children play at a family centre for internally displaced people in Ouahigouya, Burkina Faso © UNHCR/Benjamin Loyseau

The Central Sahel

Extremist groups continued to drive displacement in Africa’s volatile Central Sahel region, which includes Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. In Burkina Faso alone, more than 1.4 million people have been internally displaced over the past two years, and attacks on civilians and security forces have continued throughout the year. Mali and Niger also experienced a sharp rise in violence and displacement in 2021.

Children play at a family centre for internally displaced people in Ouahigouya, Burkina Faso © UNHCR/Benjamin Loyseau

COVID-19

As the world grapples with new COVID-19 variants and fresh waves of infection, the pandemic’s impact on forcibly displaced people has been particularly devastating. In low-income countries that host the majority of refugees, unequal access to vaccines and fragile health systems have left them exposed to sickness and death. Beyond the health risks, displaced people who relied heavily on informal work were often the first to lose their jobs and homes, increasing their suffering and the risk of exploitation.

Carlos and Rosiris, a Venezuelan couple living in Trinidad and Tobago, seen after their COVID-19 vaccination on 1 August © UNHCR/Carla Bridglal

COVID-19

As the world grapples with new COVID-19 variants and fresh waves of infection, the pandemic’s impact on forcibly displaced people has been particularly devastating. In low-income countries that host the majority of refugees, unequal access to vaccines and fragile health systems have left them exposed to sickness and death. Beyond the health risks, displaced people who relied heavily on informal work were often the first to lose their jobs and homes, increasing their suffering and the risk of exploitation.

Carlos and Rosiris, a Venezuelan couple living in Trinidad and Tobago, seen after their COVID-19 vaccination, August, 1, 2021. © UNHCR/Carla Bridglal

Syria

This year marked a decade since the start of a crisis that forced millions of Syrians to flee their homes, in what remains the world’s largest refugee crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic and an economic crisis in Lebanon and other countries in the region pushed many Syrian refugees and their host communities deeper into poverty, wiping out jobs and livelihoods. Inside Syria, more than 6.7 million people remain displaced in their own country and millions of Syrians are in need of humanitarian assistance.

A child walks across Al-Rahma camp for displaced people in north-western Syria during a severe wind storm that hit the area on 1 December © DPA/Anas Alkharboutli

Syria

This year marked a decade since the start of a crisis that forced millions of Syrians to flee their homes, in what remains the world’s largest refugee crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic and an economic crisis in Lebanon and other countries in the region pushed many Syrian refugees and their host communities deeper into poverty, wiping out jobs and livelihoods. Inside Syria, more than 6.7 million people remain displaced in their own country and millions of Syrians are in need of humanitarian assistance.

A child walks across Al-Rahma camp for displaced people in north-western Syria during a severe wind storm that hit the area on 1 December © DPA/Anas Alkharboutli

Climate emergency

In 2021, across every region of the world, climate change continued to both drive displacement and make life even more precarious for those already forced to flee. From drought in Afghanistan, to flooding in South Sudan, to intercommunal fighting over dwindling water resources in Cameroon, climate change contributed to increased poverty, instability, conflict and human movement. At the UN climate change conference (COP26) in Glasgow in November, the issue of climate-related displacement was on the agenda, but little agreement was reached on actions to protect displaced people from a changing climate.

A Fulani herdsman waters his animals at Lake Mahmouda, Mauritania. Climate change is threatening the livelihoods of communities around the Lake, including Malian fishermen who fled there to escape the impacts of climate change in their own country © UNHCR/Colin Delfosse

Climate emergency

In 2021, across every region of the world, climate change continued to both drive displacement and make life even more precarious for those already forced to flee. From drought in Afghanistan, to flooding in South Sudan, to intercommunal fighting over dwindling water resources in Cameroon, climate change contributed to increased poverty, instability, conflict and human movement. At the UN climate change conference (COP26) in Glasgow in November, the issue of climate-related displacement was on the agenda, but little agreement was reached on actions to protect displaced people from a changing climate.

A Fulani herdsman waters his animals at Lake Mahmouda, Mauritania. Climate change is threatening the livelihoods of communities around the Lake, including Malian fishermen who fled there to escape the impacts of climate change in their own country © UNHCR/Colin Delfosse

Northern Mozambique

A brutal attack by an armed group on the coastal city of Palma in northern Mozambique in March displaced some 70,000 people, bringing the total number of displaced people in Cabo Delgado province to nearly 800,000. Thousands fled to Pemba, the provincial capital, while others attempted to cross the nearby border into Tanzania to claim asylum but were pushed back.

Teresa, 82, fled violence in Mocimboa da Praia with her family and hid in the forest for a month before finding safety at a site for internally displaced people in Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique © UNHCR/Martim Gray Pereira.

Northern Mozambique

A brutal attack by an armed group on the coastal city of Palma in northern Mozambique in March displaced some 70,000 people, bringing the total number of displaced people in Cabo Delgado province to nearly 800,000. Thousands fled to Pemba, the provincial capital, while others attempted to cross the nearby border into Tanzania to claim asylum but were pushed back.

Teresa, 82, fled violence in Mocimboa da Praia with her family and hid in the forest for a month before finding safety at a site for internally displaced people in Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique © UNHCR/Martim Gray Pereira.

Myanmar

A military takeover on 1 February sparked mass protests and clashes between the Myanmar Armed Forces and ethnic armed organizations that by December had displaced some 284,000 across the country. Another 22,000 people fled across borders, mainly to India, but also to Thailand. Adding to the misery for those forced from their homes was the severe flooding that affected large parts of the country in July.

Relief items are delivered to internally displaced people at a flood-prone camp in Myanmar’s Kayin State © UNHCR/Sa Nyein Chan

Myanmar

A military takeover on 1 February sparked mass protests and clashes between the Myanmar Armed Forces and ethnic armed organizations that by December had displaced some 284,000 across the country. Another 22,000 people fled across borders, mainly to India, but also to Thailand. Adding to the misery for those forced from their homes was the severe flooding that affected large parts of the country in July.

Relief items are delivered to internally displaced people at a flood-prone camp in Myanmar’s Kayin State © UNHCR/Sa Nyein Chan

Democratic Republic of Congo

Multiple outbreaks of conflict and violence affected several parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2021, forcing thousands more to flee in a country where 5.6 million people are now internally displaced. The eastern provinces of Ituri, North and South Kivu were especially volatile and characterized by atrocities against civilians carried out by dozens of armed groups vying for control. The eruption of Mount Nyiragongo volcano near the city of Goma in May left thousands more people homeless.

A young girl stands beside emergency shelters for recently displaced people at a site in Masisi, North Kivu © UNHCR/Sanne Biesmans

Democratic Republic of Congo

Multiple outbreaks of conflict and violence affected several parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2021, forcing thousands more to flee in a country where 5.6 million people are now internally displaced. The eastern provinces of Ituri, North and South Kivu were especially volatile and characterized by atrocities against civilians carried out by dozens of armed groups vying for control. The eruption of Mount Nyiragongo volcano near the city of Goma in May left thousands more people homeless.

A young girl stands beside emergency shelters for recently displaced people at a site in Masisi, North Kivu © UNHCR/Sanne Biesmans

Pakistan

Seleema Rehman had to break down multiple barriers as a female Afghan refugee living in Pakistan to get an education and fulfill her dream of studying medicine. After securing a university scholarship and qualifying as a gynecologist in 2020, Seleema found herself on the frontline of the COVID-19 response treating women with the virus who were giving birth. This year she realized a lifelong ambition by opening her own clinic in Attock offering affordable health care to refugee and local women. For her commitment to her community, Seleema was chosen as the regional winner for Asia for UNHCR’s 2021 Nansen Refugee Award.

Dr. Saleema Rehman pictured during a visit to the school she attended as childin Attock, Pakistan © UNHCR/Amsal Naeem

Pakistan

Seleema Rehman had to break down multiple barriers as a female Afghan refugee living in Pakistan to get an education and fulfill her dream of studying medicine. After securing a university scholarship and qualifying as a gynecologist in 2020, Seleema found herself on the frontline of the COVID-19 response treating women with the virus who were giving birth. This year she realized a lifelong ambition by opening her own clinic in Attock offering affordable health care to refugee and local women. For her commitment to her community, Seleema was chosen as the regional winner for Asia for UNHCR’s 2021 Nansen Refugee Award.

Dr. Saleema Rehman pictured during a visit to the school she attended as childin Attock, Pakistan © UNHCR/Amsal Naeem