World Refugee Survey 2009 - Ghana

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 17 June 2009 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2009 - Ghana, 17 June 2009, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4a40d2a675.html [accessed 23 May 2023] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

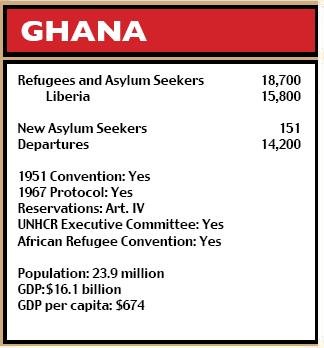

Ghana still hosted 15,800 Liberian refugees who fled the civil war in their homeland in the early 1990s. There were also roughly 1,800 Togolese refugees remaining who fled post-election violence in 2005.

2008 Summary

Ghana deported 39 Liberian refugees in the wake of a protest at Buduburam refugee camp that it broke up in March, at least 13 of whom held refugee status from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The protest began in February, when several hundred women began a sit-in to demand either resettlement to a developed country or an increase in the repatriation allowance given by UNHCR. UNHCR had offered $100 for each adult and $50 per child repatriating, but the refugees sought $1,000. The protestors blocked children from attending school and hampered delivery of supplies, according to UNHCR. After roughly a month of protests, Ghanaian police detained 630 protestors, mostly women, for demonstrating without official permission. Ghanaian authorities arrested 70 more two days after the initial arrests, including the first 16 deportees. Ghana deported 16 Liberians a week after the protests, and 23 more in April.

UNHCR and Ghanaian human rights groups had unfettered access to the detainees, and local groups filed an ultimately unsuccessful legal challenge to block the second round of deportations. UNHCR secured the release of 90 detainees shortly after their arrest, including pregnant women and unaccompanied children (35 more had permission to leave but remained with the detainees). Officials released the other 54 from the second round of arrests, which included neighborhood leaders whom Ghana argued had a duty to stop the protests.

There were 17 reported cases of rape, statutory rape, and sodomy in Buduburam refugee camp during 2008, four in Krisan camp, and two cases of rape and one of incest in the Volta region. Of the six rape cases in the court system at the beginning of the year, one defendant was acquitted, one was on remand, and four cases remained under investigation without charges having been filed. One case of rape of a minor in Krisan camp was referred to the courts and was pending at year's end. Refugees reported some threats to their lives after the protests, as Ghanaian media called for all Liberians to be deported. Most cases of assault reported in the camps were refugee-on-refugee violence.

During the year, Ghana received 151 applications for asylum. Each new applicant received a unique registration number, but not all received documents attesting to their status as asylum seekers.

At year's end, there were 23 refugees and asylum seekers, 3 of whom were women, serving prison sentences or detained awaiting trial.

During the year, Ghanaian authorities shut down a school operated by refugees because they lacked work permits, although UNHCR and the Ghana Refugee Board have intervened on the refugees' behalf.

In February, Ghana deported an Iraqi family to Syria, despite their expressed fear of returning to Syria or Iraq. Apparently brought to Ghana by traffickers who promised to smuggle them to Europe, they had lodged an asylum application, but the Government deported them before hearing it.

In April, UNHCR launched another round of voluntary repatriation for Liberian refugees, providing flights back to Liberia to 8,800 refugees during the year. Around 200 Togolese refugees repatriated in June.

Law and Policy

Refoulement/Physical Protection

Ghana is party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, its 1967 Protocol, and the 1969 Convention governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, without reservation except to the Protocol's dispute resolution provision. The 1992 Refugee Law grants refugees rights under all three instruments and prohibits their refoulement. It recognizes refugees under both Conventions' definitions and any group the Government determines to be refugees. The law establishes the Refugee Board to screen applicants, on which UNHCR has an observer role. The Government allows nongovernmental organizations to sit on the Board as well.

The law requires asylum seekers to apply to Immigration Services, the police, or UNHCR within 14 days of arrival, though the Board can allow extensions. The Board has to consider applications within 30 days, and personally interviews applicants from outside western Africa or those suspected of being former combatants. Denied applicants have 30 days to appeal to the Minister of Interior but can remain in the country with their families pending the outcome, and three months beyond to seek entry elsewhere. The Refugee Law requires the Board to issue applicants written notifications of its decisions, but does not require it to provide any reasons for those decisions. The law is silent on whether refugees can have counsel for asylum proceedings, but there are no reports of refugees doing so and the expense is beyond the means of most refugees.

The 1992 Constitution (amended in 1996) extends to "every person in Ghana" its fundamental individual rights, including life, dignity, and protection from torture and slavery, freedom of movement, and the right to work. It does, however, allow the Government to pass laws restricting the rights to own property and free movement for foreigners and allows limitation of the right to work for national security reasons.

Detention/Access to Courts

The Refugee Law prohibits the detention or punishment of asylum seekers for illegal entry or presence, but authorities can detain refugees without documentation. The Law mandates that refugees should receive identity documents and residence permits. Authorities generally respect UNHCR-issued identification cards.

High legal costs sometimes prevent refugees from appealing criminal convictions.

Refugees can pursue cases in courts, but due to the expense most resort to traditional dispute resolution methods.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Although the law authorizes the Interior Minister to establish an area in which refugees are required to live, they are free to choose their residence. There are two camps for refugees in Ghana: Buduburam and Krisan.

The Constitution allows the Government to restrict the movement of foreigners, but the Government does not hinder the movement of most refugees. Refugees from member states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) can also freely travel within other member countries. Refugees from Sudan, Somalia, Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, and Rwanda, however, cannot. The Refugee Law provides for the issuance of international travel documents to refugees, but not asylum seekers. The Passport Office issues them to refugees who can prove that they have the means to travel or an offer of employment requiring travel. Refugees working in the formal sector receive such documents with work permits stamped in them.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

Despite the Refugee Law's provision for refugees to enjoy the right of work, it is very difficult for refugees to do so legally. They have to have a sponsoring employer and apply for the permit through the Board, which would then ask the Immigration Service for the work permit via the Ministry of Interior. This process usually takes three to six weeks, sometimes ten, and most employers are not willing to wait. Companies can also acquire work permits on behalf of refugees, but have to pay a fee and there are quotas on the number of foreigners they can employ.

Unless they have Ghanaian partners, the law treats refugees as foreigners, and they can open businesses limited by guarantee once they have a mission statement and can fulfill tax requirements.

The Constitution allows restrictions on non-Ghanaians' economic activities.

Refugees can own movable property and open bank accounts but the Constitution categorically bars foreigners from any freehold interest in land or any lease greater than 50 years. Nevertheless, several legal residents lease land for 99-year periods. In Buduburam, some refugees lease property from Ghanaians on build, operate, and transfer agreements.

Public Relief and Education

Refugees in Krisan camp as well as those in the Volta Region have access to government hospitals and clinics. UNHCR continues to seek similar access for refugees in Buduburam and urban areas.

The Government does not provide financial or other assistance to refugees.

Refugees are entitled to the same school subsidies as nationals if they attend government-assisted schools. Those in Krisan camp receive free education on par with nationals. The Constitution restricts to citizens its requirement that the Government provide education and social security. The Refugee Law calls for the establishment of a Refugees Fund to aid refugees.

Aid groups have to register with the Government but generally have access to the camps. The National Development Planning Commission does not include refugees in its 2005 Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy II (2006-2009) that it prepared for international donors, except to identify them as a "public safety and security" issue. Government efforts to adopt a National Youth Policy do not include refugee youth as part of the process. Under the U.S. Millennium Challenge Account, the Government developed a plan that could potentially benefit refugees involved in the agricultural sectors, but it did not specifically include or aim to assist them.