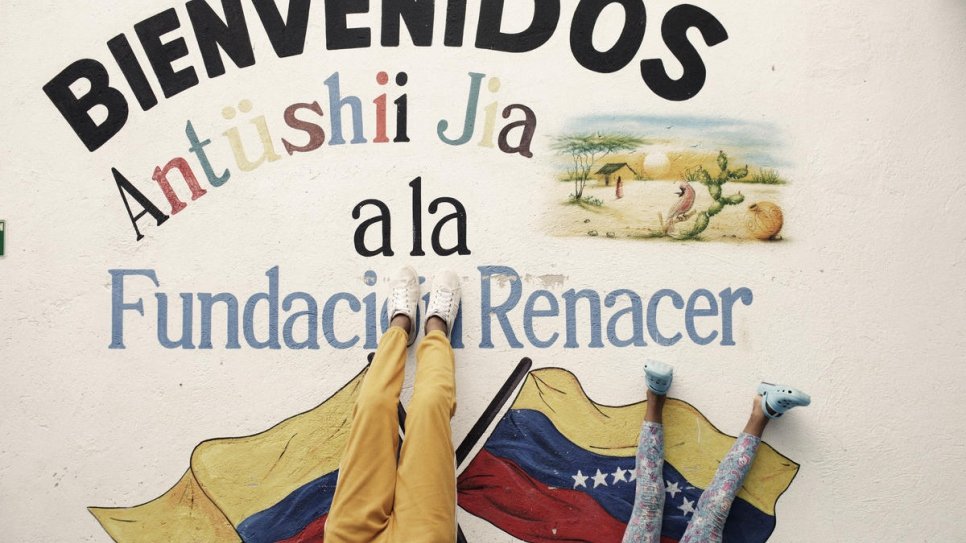

For survivors of childhood sexual violence, a second chance in Colombia

Since it opened its doors 32 years ago, Fundación Renacer has worked to give children and teens who have endured sexual violence the tools they need to rebuild their lives.

A young resident of the Fundación Renacer, a Colombian NGO that helps survivors of childhood sexual exploitation.

© UNHCR/Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Jessica* does not talk about her childhood often because, on the rare occasions when she does broach the topic, she is unable to hold back the tears.

Now age 30, Jessica is a successful entrepreneur and proud mother of six-year-old twins. But back when she was 12, she suffered an almost unthinkable betrayal: Her long-estranged mother forced her into childhood sexual exploitation.

“When you’re going through something like that, fear takes you over. It’s as if your hands were tied,” said Jessica, who was born in Barranquilla, on Colombia’s Caribbean coast. “You don’t know what to do.”

She found help after being picked up by police and sent to live in a home run by the Fundación Renacer, or ‘Foundation Rebirth’ in English, a Colombian non-profit that for more than three decades has been working to help children and adolescents rebuild lives shattered by sexual violence and exploitation.

“Being sent to the Fundación Renacer marked the start of a new life for me.”

In addition to outreach work with vulnerable groups, the organization currently operates two of the three residential homes for survivors of childhood sexual violence in existence in all of Colombia. One is in the coastal city of Cartagena, and the other in the far-eastern border region of La Guajira – which has seen an alarming spike cases of sexual exploitation among Venezuelan refugees and migrants fleeing the ongoing crisis at home.

Fundación Renacer works closely with Colombia’s child protection agency, the Government Institution for Family Welfare, or ICBF. The ICBF places children and teens in the organization’s homes, where they go through a rigorous rehabilitation process that includes individual and group therapy sessions, exercise and other activities, as well as school.

“When they first arrive at the Fundación Renacer, they’re filled with guilt and shame, and many no longer want to live,” said Mayerlín Vergara Pérez, a veteran staff member of the organization who has headed the home in La Guajira since it opened in 2019. “They have no dreams, no projects for their lives, and they have real difficulties in interacting with others, as well as giving and receiving affection.”

Conflicts among the several dozen children and teens living in the homes at any given time are commonplace, and the multidisciplinary staff – which includes a social worker, a lawyer and a nutritionist, in addition to psychologists and educators – are on hand 24 hours a day to help them learn how to resolve their differences. And because of the profound trauma the children have endured, the staff must be constantly on high alert for threats of self-harm.

But little by little, Mayerlín says, the children adapt to their new environment and, far from danger and surrounded by caring and supportive adults and other children who have been through similarly traumatic experiences, they are able to process their pasts and plan for new futures.

“When they first arrive at the Fundación Renacer ... many no longer want to live.”

“Being sent to the Fundación Renacer marked the start of a new life for me,” said Mau de Oro, a 29-year-old from Bogotá who was just five years old when he first suffered sexual violence – a pattern of abuse he says led to numerous suicide attempts.

“I was in line to become one more statistic, another young person who ends up taking their own life,” he said. But at the home, “my wounds began to heal, and I started to feel at peace … and started to recover my will to live and to dream.”

Mau also credits his three years at Fundación Renacer with giving him the courage to pursue a career in music. As a Christian rock musician, he has spent much of the past decade on the road, taking what he calls his “message of change” to audiences throughout Latin America.

Mau is not alone. Since its founding in 1988 by a Bogotá-based psychologist, Luz Stella Cárdenas, the Fundación Renacer has served an estimated 22,000 children and teens. Among them, there are countless success stories – survivors of child sexual violence and exploitation who have gone on to become everything from chefs to lawyers to doctors to accountants.

With the influx of Venezuelan refugees and migrants fleeing food and medicine shortages, spiralling inflation and widespread insecurity back home, the profile of those served by the Fundación has changed in recent years. Of the around 40 children living in the organization’s new home in the border region of La Guajira, around half of them are Venezuelans – some whom were forced into sexual exploitation by extreme poverty, others, the victims of human trafficking networks.

“It was an absolutely agonizing situation,” the home’s director, Mayerlín said, adding she hopes to help the Venezuelan children on to futures as bright as those of many of the Colombian sexual violence survivors who preceded them at the Fundación.

Juana,* a 26-year-old Colombian woman who spent five years at Fundación Renacer after running away from a troubled home at age 12, falling into a life of sexual exploitation and narrowly escaping being trafficked by a criminal gang, said she emerged from the home transformed.

“I was no longer that child who had been sexually exploited,” she said. “I was another person altogether.”

*Names have been changed for protection reasons.