In Liverpool, a law clinic keeps fighting to support stateless people

"It is like an indefinite prison because you do not know when you are going to get out." An unknown number of stateless people from around the world end up in the UK and often find themselves stranded after being denied recognition from their embassies and having their asylum claims rejected by the authorities. © UNHCR/Greg Constantine

The UK has made some progress in addressing the issue of statelessness in recent years and one organisation - the Liverpool Law Clinic - has played a crucial role in keeping it on the agenda and trying to galvanise the global IBelong campaign to end statelessness by 2024.

The Law Clinic, the University of Liverpool’s in-house legal practice, is part of a small, active network of specialist legal organisations across the UK working to address the challenges of stateless people, fighting to win them the legal rights and security they need.

The Law Clinic started working in this area in 2013 after the government introduced a new procedure to allow stateless people to gain legal recognition and permission to stay. Prior to that, many who were stateless or at risk of statelessness were unable to access advice or solutions; many ended up destitute, homeless or otherwise marginalised.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, spoke to Judith Carter, one of the Law Clinic’s solicitors, who works on statelessness applications and engages in research, policy advocacy, and training students and legal practitioners. From modest beginnings, the clinic took on more cases from 2016, thanks to a grant that allowed it to employ a dedicated case worker, Jo Bezzano.

“The number of cases we were able to take on increased significantly,” Carter said. “Having Jo on the team has made a huge difference and allowed us to offer advice to so many more people. At any one time we are now advising and representing approximately 15 cases.”

“It’s really a ridiculous thing – imagine you want to get a phone contract and you can’t get a phone contract. It’s something silly nobody thinks about.”

It is difficult to accurately estimate numbers of stateless people in the UK without status because they have often been forced into the shadows. The introduction of the statelessness determination procedure was crucial, offering a path to protection to those who previously lacked potential solutions.

The procedure appears in the UK Immigration Rules. Applicants register online, some are interviewed in person, with decisions made by a team at the Home Office. They must demonstrate that they are stateless and not admissible to other countries with a right of permanent residence, as well as meeting other criteria.

If an application is refused, there is no statutory right of appeal – the only potential remedies are administrative review (by the Home Office), judicial review (if a material error of law has been made), or a new application. These options can be lengthy and costly, and it can be difficult to find qualified solicitors to take cases. None of these remedies complies fully with UNHCR’s recommendations for procedural safeguards.

Relatively few have received positive decisions, and while the procedure can be life-changing, Carter and other advocates hope for further progress in addressing the ongoing challenges in decision-making and the broader system.

“There are around 160 stateless people who have now received UK resident permits because of the statelessness determination procedure,” she added. “But those are a tiny minority of the more than 9,000 that we estimate have applied since 2013.”

According to Carter, the key issues that have held back further progress under the procedure include the time applications take to be considered; the onerous standard of proof applied; the difficulty in accessing legal aid in England and Wales; and the lack of an effective right of appeal. These factors, she said, “weaken what could in theory be a good procedure.”

In the coming months, UNHCR will publish an audit of the procedure and a participatory assessment, featuring interviews with those who have navigated the system.

Rashid*, a Palestinian, spoke to UNHCR as part of the assessment. “People don’t realise how frustrating it is to have a life without that piece of paper,” he said. “It’s really a ridiculous thing – imagine you want to get a phone contract and you can’t get a phone contract. It’s something silly nobody thinks about.”

Globally, an estimated 10 million do not have nationality through no fault of their own. This can have a devastating impact. The lack of nationality often leads to the loss of other basic human rights, and can leave people vulnerable, all too often becoming ‘invisible’ and on the fringes.

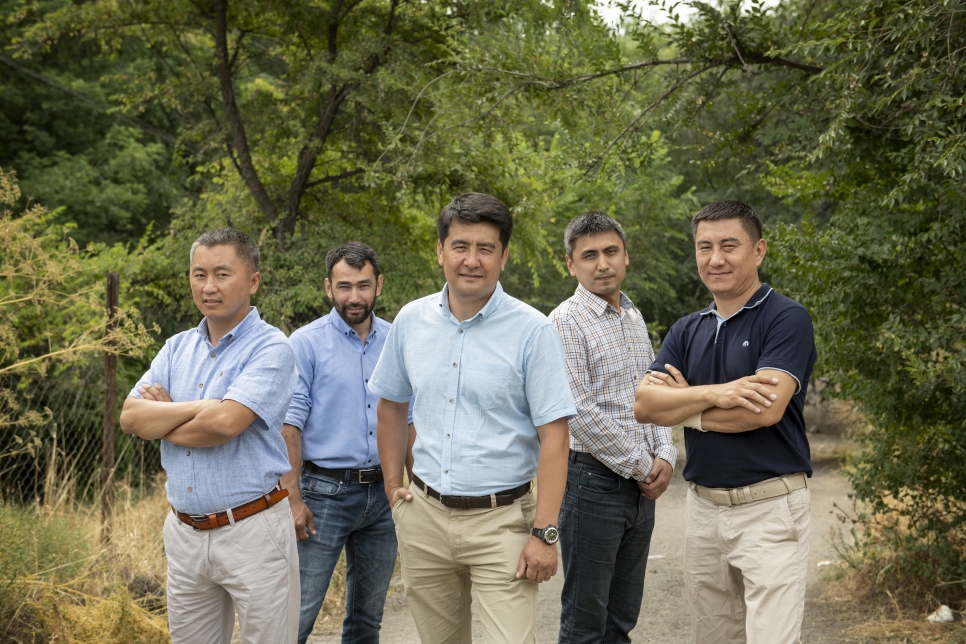

Statelessness had been a longstanding problem in Kyrgyzstan since the collapse of the USSR. Thanks to the work of Azizbek Ashurov and his team of lawyers, the country has managed to effectively end statelessness in the country. In the UK, the stateless population is diverse, often hard to find, and there are varied reasons for statelessness. © Chris de Bode

The Law Clinic has done its part in trying to give momentum to UNHCR’s global IBelong campaign.

Launched in November 2014, the campaign aims to end statelessness by 2024, by identifying and protecting stateless people, resolving existing situations of statelessness and preventing the emergence of new cases. Through legal advocacy and awareness-raising, UNHCR works with governments and partners globally at achieving the goals.

“In our early years, a number of our clients at the clinic noticed the IBelong campaign poster in the reception area,” Carter said. “For them, it was a powerful reminder that there was a global effort to support people like them, and that our work here in Liverpool was part of a much bigger effort.”

Progress is being made. On November 11, UNHCR will mark six years of IBelong. Since the launch, there have been 25 new accessions to the UN Statelessness Conventions and over 341,000 stateless people worldwide have acquired a nationality in places as diverse as Kyrgyzstan, Kenya, Sweden and the Philippines. In total, 21 States, including the UK, now have statelessness determination procedures. At a high-level meeting a year ago, 360 pledges were submitted towards IBelong’s aims by states, civil society and international and regional organizations.

𝗡𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝗮𝗹𝗶𝘁𝘆.

— UNHCR United Kingdom (@UNHCRUK) November 10, 2020

It's not a privilege. It's a right.

UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador Cate Blanchett explains why it's more important than ever to #EndStatelessness. pic.twitter.com/5l6jniEYct

The reasons why individuals find themselves stateless vary, with the causes often unique to each person. Many people fall into statelessness when states break up, for example following the collapse of the USSR in the 1990s or the split of South Sudan from Sudan in 2011. In some countries, discriminatory laws don't allow women to pass their nationality to their children - leaving children born to single mothers or stateless fathers without nationality. Some may simply have lost or never been provided with documentation. Others’ statelessness results from discrimination based on ethnicity or race, as is the case with the Rohingya from Myanmar.

Hence, resolving statelessness can be painstakingly slow, and the assistance of expert legal practitioners is essential.

*Name changed for protection reasons