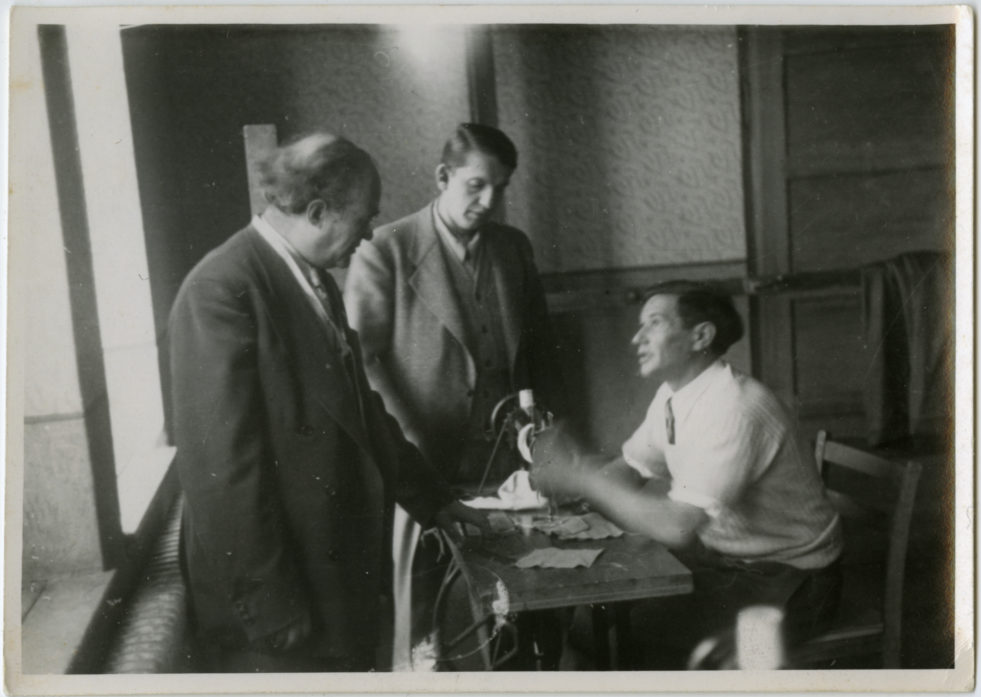

In 1947, Samuel Herbst and Samuel Posluns, two members of the Canadian “Garment Workers Scheme” committee charged with bringing tailors from displaced persons’ camps in Europe after WWII, speak to an unidentified tailor. © Tailor Project photos, 1947. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 70, file 5.

Seven decades later, The Tailor Project’s legacy lives on in a brighter future for refugees

By Fiona Irvine-Goulet

Like threads woven through the fabric of history, 90-something Montrealer Irving Leibgott, originally from Poland, and 43-year-old Mohamad*, a Syrian refugee living near Toronto, are inexorably connected.

In 1948, Leibgott, an Auschwitz survivor, was one of the world’s millions of displaced persons unable to return to their homes in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Then 24, the Jewish tailor arrived in Canada under what was called the “Garment Workers Scheme,” an unprecedented federal government/Canadian Jewish Congress job initiative charged with bringing 2,500 displaced tailors and their families to the country to fill vacant positions.

Tailors were guaranteed one year of employment with pay and rights equal to other employees in Canadian garment factories. Displaced families—all who had suffered unspeakable hardship—were able to start new lives and become proud Canadians.

Leibgott recalls that when he stepped off the boat in Montreal, “I didn’t have anything—not one penny.”

Seventy years later, Mohamad represents a new chapter in honouring the legacy of the Garment Workers Scheme, now renamed the Tailor Project.

Originally from Afrin, in northern Syria, Mohamad came to Canada with his wife and young daughter in 2018, arriving as a refugee through a private sponsorship.

Back home, Mohamad ran his own small successful clothing factory producing children’s clothing and jeans. A member of the Kurdish ethnic minority, when the Syrian conflict had barely begun in 2011, Mohamad was shot four times and after a long recovery, fled to Turkey with his family.

Facing more oppression there, he had almost lost hope when word came that the family could resettle in Canada. “It’s hard to express my feelings when I heard the news,” Mohamad says through a translator.

Just as in 1948, the benefits are enormous: refugees become productive members of society who enrich our country economically, culturally and socially.

Now Mohamad is working with the Tailor Project on the launch of an initiative that will create limited edition “Common Thread” shirts designed to increase awareness and understanding of the value of immigration.

An endeavour of Impakt Labs, a not-for-profit organization that incubates innovative solutions to social issues, the Tailor Project began as a research initiative in 2017. Larry Enkin, son of Max Enkin, who was the chairman of the original Garment Workers Scheme government committee dispatched to find tailors in the displaced camps in Europe, wanted to shine a light on this little-known part of Canadian history. He met with his friend, Paul Klein, Impakt’s founder and CEO, and the project was born.

So far, Impakt has interviewed almost 100 former tailors and their families to record their stories of loss, survival and resiliency.

That has led to a reimagining of the original 1948 economic initiative, with the belief that a similar model could help refugees today experiencing many of those same challenges to successful integration—all by using meaningful employment as the foundation.

Sam Bennett, social program manager at Impakt, researched the employment profiles of refugees, and discovered the top areas of employment for newcomers, including construction and professional fields.

“To my surprise, the needle trades, taken as a whole, was the next group on the list,” Bennett says.

Understanding that the Canadian garment industry has hugely shrunk since 1948, the Impakt team’s assessment saw a market niche in the higher-end clothing market. The reimagining came full circle: produce a limited number of quality, made-to-measure shirts employing refugees like Mohamad with decades of industry experience—and a drive to succeed.

Just as in 1948, the benefits are enormous: refugees become productive members of society who enrich our country economically, culturally and socially.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau accepts a custom shirt from Mohamad, Tailor Project associate, on May 1, 2019 at a Holocaust Remembrance Day event in Toronto

On May 1, 2019, Holocaust Remembrance Day, Mohamad presented the Tailor Project’s first custom-made shirt to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at a special service honouring the Jewish tailors at Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto.

Impakt, with its partners, including Jumpstart Refugee Talent, an agency that works with newcomers to connect them with meaningful education and employment opportunities, is committed to finding new ways of encouraging more businesses to hire refugees.

“Part of the grander vision is that one day we’ll have this reimagined sewing studio, where there might be child-minding, vocational-specific ESL classes and extended supports for mental health and other services,” Bennett says.

Their ultimate goal is to make Mohamad and other employees equity stakeholders in the enterprise. “Before, I had no future. Now the sky is the limit,” Mohamad says.

*To protect his family, Mohamad’s last name has not been given.