© UNHCR/Arturo Almenar

A rapidly increasing number of women, children and men from the North of Central America are finding in Mexico the opportunity to be safe and rebuild their life. Has Canada a role to play?

By Jean-Nicolas Beuze, UNHCR Representative in Canada

I am just coming back from Mexico City where I met Juan, a 17-year-old boy from Honduras. Juan is from San Pedro Sula, one of the most dangerous cities in the world with more than 111 murders for 100,000 inhabitants – by comparison, Canada’s rate hovers around 1.7. From an early age, he endured the threats of neighbourhood gangs who tried to forcibly recruit him into trafficking of all kinds: armed extortion, drug trade, sexual exploitation. He knew all too well the price to pay if he did not cooperate. But he refused to be associated with such horrendous criminal acts. Not only was Juan severely beaten, but his sister was threatened with rape. I believe him when he tells me that his only way out was exile. The gangs, I know from our work on the ground, can reach you almost wherever you are in Honduras, and even beyond in the region. He now lives in a shelter managed by Mexican nuns with the support of the UN Refugee Agency. When I left, I saw him sitting on a bench with a young girl. I did not dare ask if she was his sister – if she had the chance to find safety as well.

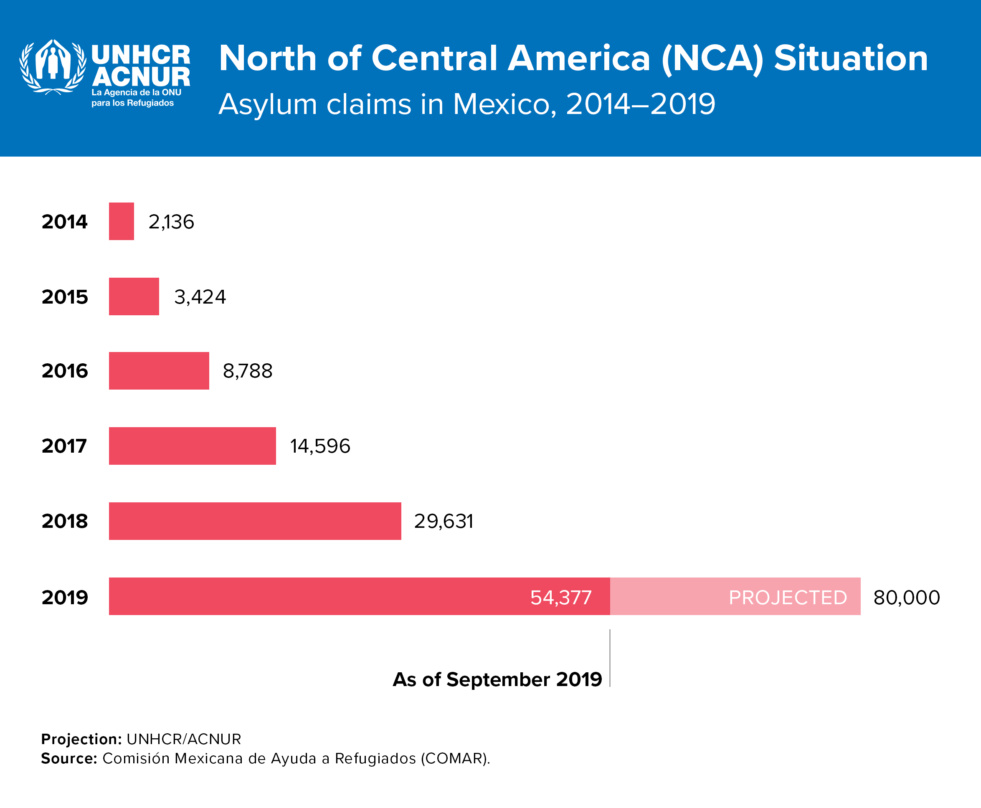

Juan’s story is terrifying, and yet it is shockingly banal in the region. Our neighbour, Mexico, is seeing a sharp increase in the number of asylum-seekers and refugees: figures have doubled every year since 2015. Over 54,000 asylum claims have been made in Mexico so far in 2019, 68% of which come from the North of Central America (mainly Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala) – about as many as in Canada in 2018 (55,000) – for an expected total of 80,000 asylum-seekers by the end of the year, according to estimates from the Mexican Refugee Commission (COMAR). But in Mexico, many more could – or should I say: should – ask for asylum. They simply do not know they have this right. They are fleeing the extreme violence of armed gangs that control entire sectors of the economy and society, imposing their cruel law and targeting anyone who might oppose their forceful grip. The majority of them are women and children.

Asylum claims in Mexico

I was struck by the number of adolescents and young children I met in shelters for migrants – and left speechless when I learned that the youngest unaccompanied child hosted in the Mexico City shelter was only eight. Alone. Thousands of kilometres away from home and his loved ones. In fact, families themselves often send children away because they fear for their lives. For their protection. I cannot imagine what is on the mind of these parents who have no choice but to send their kids on the dangerous routes of exile. Left on their own, they must survive the perils of the long journey to find a safe haven – dodging traffickers and smugglers, escaping border patrols’ and police’s attention. Some hope to join a family member in the U.S., others do not know where their travels will end. And many are intercepted by the gangs or the authorities and are simply returned home. Without a chance to tell their story and be protected.

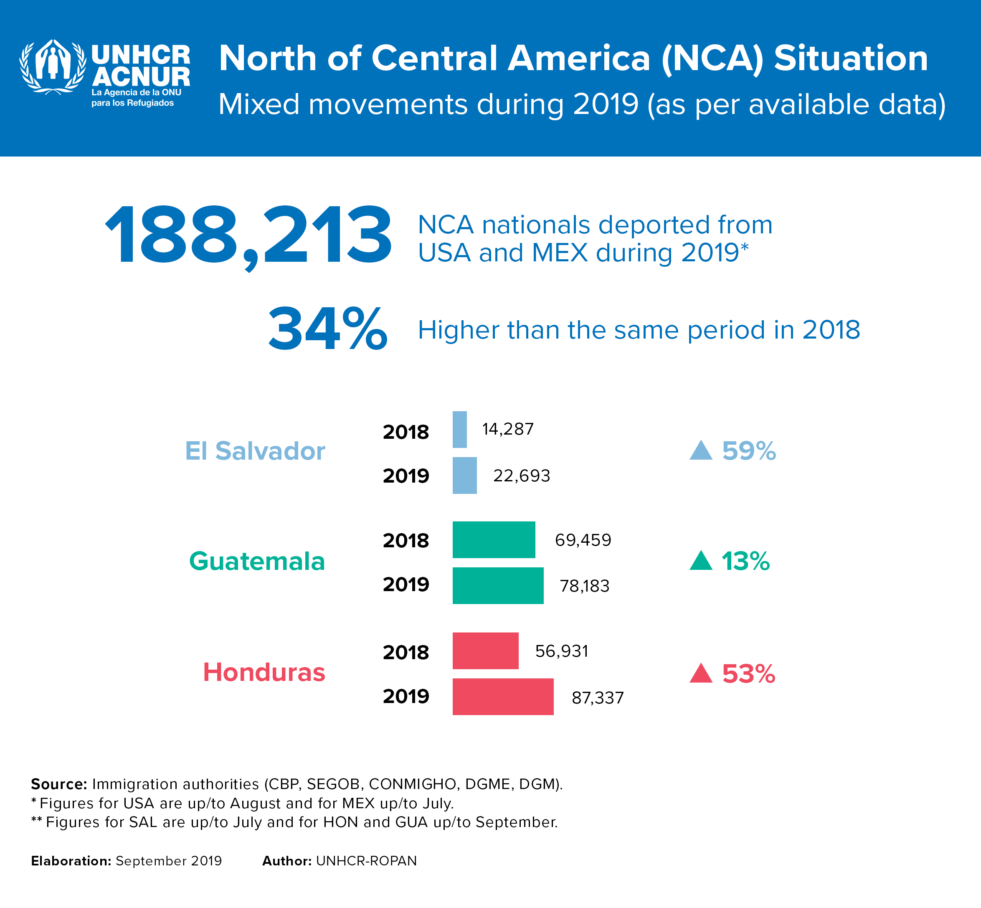

Mixed movements during 2019

This year alone, more than 180,000 nationals from the North of Central America region have been returned from Mexico and the U.S. This is a 34 per cent increase compared to the same period last year. One can hardly grasp just how fear and desperation turn these trips into revolving doors of repetitive escapes from violence. Most of these vulnerable people will indeed flee again, as they have no prospect of living in safety and dignity in their home country. Last year, I met a group of seven adolescents who had attempted to seek refuge in either Mexico or the U.S. – they were now part of one of our programs to support those who have returned, and children in particular. One of them was a 17-year-old girl, Maria, who had been gang-raped since the age of 12. She candidly admitted that she had been sniffing glue to forget about her ordeal. And she was waiting for an opportunity to run away from the shelter and attempt, one more time – despite three failures already – to reach her aunt in New York City. She otherwise would not make it here, she said. Maria recognized that she would fall back into the gangs’ hands if she were to stay in Honduras. Being raped and trying to forget by taking drugs, she told me, necessarily meant that she would end up dead on the street, forgotten by all. She was adamant about changing her destiny. I was amazed by her strength and determination to turn her life around.

On this last trip, I visited Saltillo, the capital of the northern state of Coahuila, located in what is often referred to as Mexico’s industrial corridor. The experience was eye-opening: too often, we believe that safety, education or access to decent jobs for the Marias and Juans of this world are primarily – or even exclusively – found here in Canada. And while we must keep our doors opened, our responsibility also lies in supporting countries like Mexico and so many others that stand ready to protect and give refugees the chance to get their life back.

© UNHCR/Arturo Almenar

In Saltillo, I visited a single mother with her two kids, and she explained well how Mexico had become a solution to their plight. Gabriela fled the day her ex-husband, a member of the neighbourhood gang, shot their nine-year-old son because he wanted to keep him after an acrimonious divorce. His links to the gang meant total impunity – and no protection from the authorities. Gabriela left the following night. Without even saying goodbye to my own mother, she adds, a tear rolling down her face. She joined her brother and his family in Chiapas, at the border between Guatemala and Mexico. It was there that her son got medical attention for the first time.

But there are no job opportunities for refugees in Chiapas: 73 per cent of them are unemployed. And 82 per cent are out of school – by lack of space in those schools, out of fear that they might be snapped by gang members crossing borders. Through UNHCR’s intervention, the family was brought to Saltillo. With our help, they found a house and a job with a decent pay in a nearby factory. I can see they are regaining control over their lives. They can make decisions on their own. They can find joy again in the smallest things – like Gabriela’s daughter, whom I’m watching as she plays with her snowman doll. UNHCR’s relocation and economic integration programme is all about restoring refugees’ dignity. It’s hard to believe that Gabriela’s son who is standing in front of me, trying to say a few words in French before getting ready to go to school, is the same boy who was struggling with nightmares and isolation just a few months ago. All children can go to school in Saltillo.

© UNHCR/Arturo Almenar

Mexico’s industrial corridor is a region where unemployment is very low and staff turnover very high. Refugees, however, tend to stay longer on the job. Because they need stability. Because they want to feel that they can re-focus their attention on putting their children back in school. Because they hope they can rebuild their lives with the stability of an income. And many companies are now hiring them in Saltillo, including Canadian companies like Palliser, which manufactures furniture sold in Canada. For Palliser and others, hiring refugees has become a crucial component of their business model, an integral part of growing the economy and achieving prosperity. In Mexico like in Canada, refugees contribute to the local economy.

Solutions exist in Mexico. Innovative partnerships between private businesses – including Canadian ones, Mexican authorities and UNHCR such as those protect families from having to risk their lives on the road to exile and fall prey to traffickers. Protecting refugees means keeping our doors opened here in Canada, but it also means supporting front-line countries that can offer them protection and socio-economic integration. The two must go hand in hand.

Names have been changed to protect the identity of the refugees mentioned.