Young Tajik family finds home with Polish politician

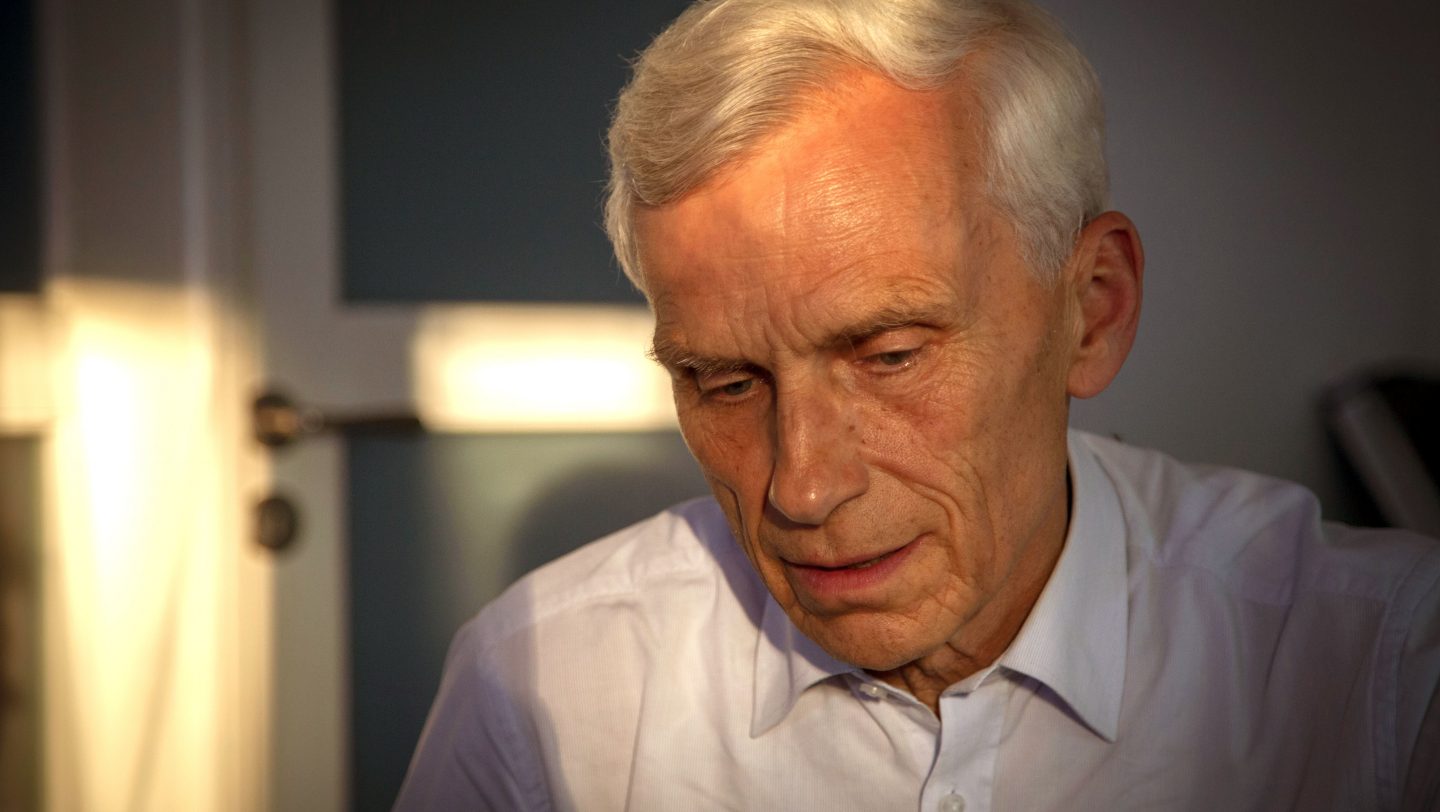

Politician Marcin Święcicki matched words with deeds when he and his wife took a refugee family into their home.

Polish politician Marcin Święcicki was arguing in a TV debate that refugees should be accepted when a journalist asked if he would be willing to host any in his own home. Without thinking, he said “yes”.

Soon after, an NGO that helps refugees find housing got in touch to see if he was a man of his word. It turns out he was.

Mr. and Mrs. Święcicki have been like a mother and father to us, and like grandparents to our little girl

The NGO linked him up with some refugees in need and for nearly a year, Mr. Święcicki and his wife Joanna have been sharing their home with a family from Tajikistan.

“Mr. and Mrs. Święcicki have been like a mother and father to us, and like grandparents to our little girl,” says Sitora, who came to Poland just over a year ago with her husband Sanjar. Their daughter Simin is nine months old.

Back in Tajikistan, Sitora, 27, worked as a journalist for a TV channel financed by an opposition party. “I was not a member of the party, just a news reporter,” she says.

But when the party was banned and some of its top leaders jailed, Sitora was threatened. Husband Sanjar, 29, a journalist on a state TV channel, found himself in trouble by association with her.

The couple fled via Kyrgyzstan and Moscow to Minsk, from where they took a train to the Polish border. They sought asylum and found shelter in a refugee reception centre. Sitora was pregnant by this time.

But they did not stay long in the refugee centre, as the Ocalenie (Salvation) Foundation quickly placed them with the Święcicki family through its Welcome Home programme. They now have refugee status.

“If we had not been invited here, we would not have had a chance to leave the camp,” says Sanjar. “We simply could not have afforded to rent a place ourselves.”

The young Tajiks have a room of their own at the top of the three-story, suburban house while the ground-floor kitchen is common to all. Mr. and Mrs. Święcicki felt able to share their space because their own four children were grown up and had left home.

But we don’t think of them as refugees. We are a happy family together. They have enriched our lives.

Mr. Święcicki, 72, who was Minister for Foreign Economic Relations from 1989 to 1991 and Mayor of Warsaw from 1994 to 1999, is still active in politics as a member of the Sejm (parliament) from the opposition Civic Platform.

“When we met him, we had no idea he was a famous person,” says Sitora. “We see him every day and he seems so ordinary and modest. I cannot imagine that parliamentary deputies in our country would do what he has done.”

It is evening and Sitora and Sanjar are in the kitchen, making a meal. Mr. Święcicki comes in from his office and the first thing he does is take off his tie and throw it on the sofa. He picks up little Simin and carries her out into the garden. Mrs. Święcicka is out somewhere.

Mr. Święcicki, who is of a generation to remember political repression in Poland, can understand what Sitora and Sanjar have been through. Initially, they communicated in Russian but now they try to speak Polish.

“We talk about the situation in Central Asia,” he says. “But we don’t think of them as refugees. We are a happy family together. They have enriched our lives.”

Among other things, Sitora and Sanjar have introduced the Święcickis to Tajik cuisine and they eat plov (Central Asian rice dish) as well as pierogi (Polish dumplings) at family gatherings.

Sitora and Sanjar are comfortable at the Święcickis’ house but as soon as they can, they want to stand on their own feet and find their own place. Both are learning Polish, and Sanjar is working as a cook.

Eventually Sanjar hopes to set up an independent Tajik news channel in Europe, or perhaps have his own small business, a restaurant maybe. Sitora is interested in studying sociology, or going into PR and advertising when Simin is a bit older.

The Święcickis have put no time limit on how long Sitora and Sanjar can stay with them and of course they want the best for the couple. “I hope Sanjar will be able to work in his profession,” says Mr. Święcicki, “although that is not so easy in a foreign country. And I hope they find a good place for the child.”

Conscious that he could be seen as making political capital out of his generosity to refugees, Mr. Święcicki has not spoken much about it in public. “But journalists will always find out,” he says. “I am not advertising it but I cannot deny it.”

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter