Prague students play out an ordeal that is real for refugees

A simulated drama helps school students to understand how bewildering the asylum process can be for refugees.

Officers in peaked caps issue incomprehensible instructions. Refugee applicants are herded, separated and left bewildered. For school students in the Czech Republic, this is a simulated drama of the asylum process – not real life but an exercise in empathy.

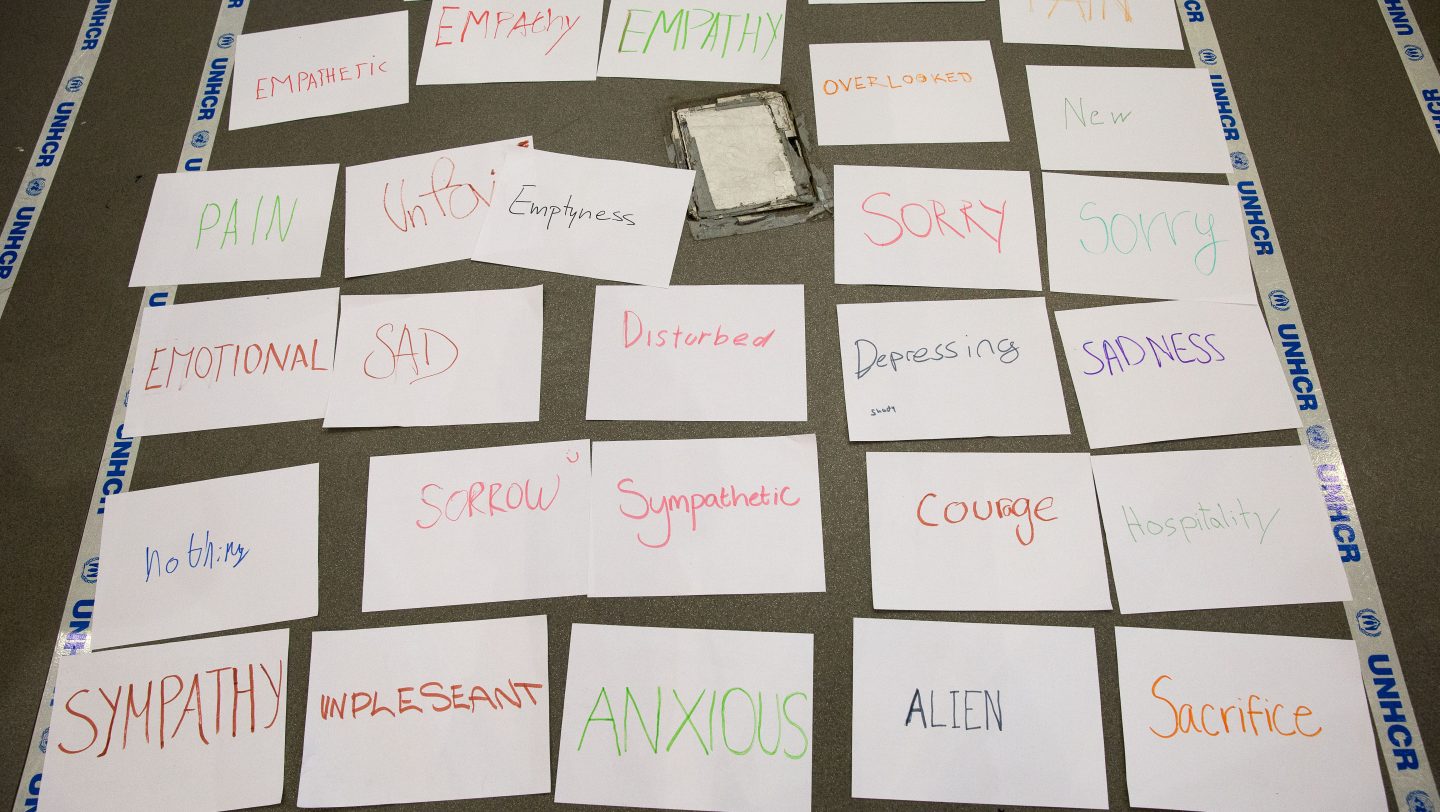

“I feel strange, out of place,” says Jef, one 17-year-old taking part in the role-playing, educational game.

“Yes, isolated, ignored, it’s a bit scary,” says his classmate Maija.

Hello Czech Republic, a UNHCR schools programme first tested in Sweden, has come to the Prague British International School to stimulate discussion about refugees. The students here are perhaps more open to the subject than average Czech youngsters as they come from all over the world. Jef is half Belgian, Maija is British.

The morning begins with the students, in the position of refugees and migrants, queuing up to see “immigration officers”, played by UNHCR staff, from an imaginary country called “Farlandia”. The late Czech playwright, dissident and president Vaclav Havel seems to look down benignly on this piece of theatre from his portrait on the wall.

The “officers” bark orders in “Farlandish”, a made-up language that nobody understands. The “refugees” try to make sense of application forms in this abracadabra. Without apparent rhyme or reason, most are sent to sit on the floor while a few are directed to the seats, their papers marked with a red cross. What does this red cross mean? Is it the Red Cross? Are they the lucky ones or have they been rejected?

“I think this is excellent,” says drama teacher Cindy Kennaugh from the USA. “I have done simulations myself. This method engages the students. It is interesting to see how most have been supporting each other, although some have been competing and cheating. They are looking for a pattern in the confusion.”

Soňa Rysová from UNHCR’s Prague office is playing the part of an officer, wearing a party police hat and sunglasses to cut off eye contact. “It’s difficult to be so strict, making decisions about someone’s life,” she says. The role playing has helped her to understand the stress of immigration officers, who have to be fair and stay detached.

As for her fluent “Farlandish”, she says she made it up from a mixture of the languages she knows – English, Spanish and German. “I use Spanish, twisted English. I say ‘rapido, rapido’ when I want to hurry them up.”

The students are given a task, to present their case to the authorities of “Farlandia”, a poor country with some unusual customs. Here chicken and ducks are sacred and fir trees must not be cut down for Christmas. Depending on how the “applicants” frame their appeal, they will be accepted or rejected for asylum.

“I was and still am mixed on the whole subject (of refugees and migration),” says Pepijn, 18, born in Prague to Dutch parents.

Meanwhile, there is a factual talk about Kurdistan and a film called Shadi, about a Kurdish girl who is forced to flee her homeland and seek safety in Sweden. In her new Nordic environment, she misses her mother and the mountains of home.

Mr. Ibrahim, a real refugee from Syria, also makes an appearance as a “human library”, telling the students of his five-year effort to settle in the Czech Republic, where he now works as a clerk in the post office.

“I don’t mind being a ‘human library’,” he says patiently. “When I came to the Czech Republic, I noticed how little experience they (locals) have with foreigners. I want to change their ideas about our people. I explain that Syria has an ancient culture and history, and sadly much has been destroyed. Unfortunately, they know very little about this.”

For some of the students, the film and meeting with Mr. Ibrahim have a greater impact than the role playing.

“With the drama, I knew we were just acting,” says Sebastian, 17, who is half Czech, half Italian. “But the film and Mr. Ibrahim’s talk really moved me and made me feel what it is like to be a refugee.”

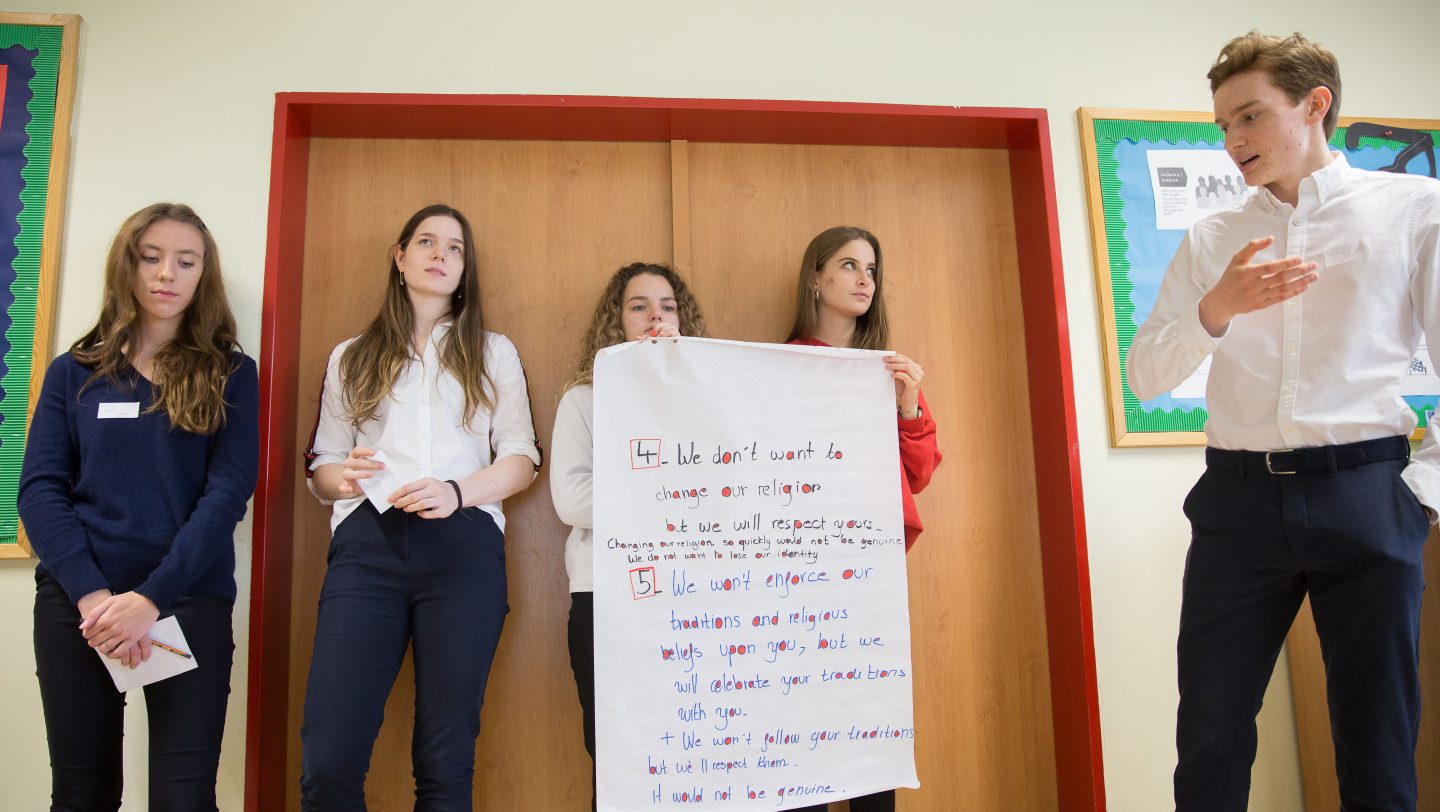

Back to the exercise to appeal to the “Farlandians” and the students are debating how humble or demanding they should be. Should they be sincere or say what they think the authorities want to hear?

“We are appealing out of desperation,” says Arturo, 17, from Spain. “Perhaps we should say what will make us look best.”

“We are in no position to make demands,” says Maud, 18, from the Netherlands. “We feel the pressure to fit in.”

The debate swirls around food and religion. Some argue that they should ask “Farlandia” for the right to build their own church. Others think practicing their faith at home might be a safer option.

“What religion?” asks Sebastian, “atheism?”

Simon, 16, from Belgium, has understood that in “Farlandia”, he cannot eat poultry in public. But what about a little omelette at home?

“You are not allowed to eat anything chicken-related,” snaps one of the peaked caps.

“And what if I do?” asks Simon, to laughter from the class.

The event has been fun and illuminating, although it may not have changed minds radically.

“I was and still am mixed on the whole subject (of refugees and migration),” says Pepijn, 18, born in Prague to Dutch parents. “On the one hand, on the other… It is complicated and I’m middle of the ground.”

Others are more fired up. Justyna, 19, from Poland, says she will definitely try to find out more about refugees. And Maud goes further, saying the experience has inspired her to consider doing volunteer work with refugees.

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter