After finishing top of her class in primary school, Hina was not able to get a place in secondary school for the simple reason that out of 500 available places, only one could be allocated to a refugee. Refusing to give up, she applied to a private college and won a scholarship. But to get to university she faced exactly the same problem: out of 200 available places, there was only one reserved for refugees. Once again she won through thanks to her excellent grades. Today, her DAFI scholarship is helping her to finish her degree. ©UNHCR/GORDON WELTERS

This report tells the stories of some of the world’s 7.1 million refugee children of school age under UNHCR’s mandate. In addition, it looks at the educational aspirations of refugee youth eager to continue learning after secondary education, and highlights the need for strong partnerships in order to break down the barriers to education for millions of refugee children.

Education data on refugee enrolments and population numbers is drawn from UNHCR’s population database, reporting tools and education surveys and refers to 2018. Age-disaggregated data is not available for the whole refugee population. Where this data is not available, it has been estimated on the basis of available age disaggregated data. The report also references global enrolment data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics referring to 2017.

Investing in humanity:

why refugees need an education

Introduction by Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees

Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, meets young Rohingya refugee students in Kutupalong refugee settlement, Bangladesh. © UNHCR/WILL SWANSON

How can you invest in a refugee, and what do you get back for your investment?

In today’s world of business and finance, making an investment – whether in shares and bonds or property, gold, lottery tickets or the latest start-up – is quick and easy. The big trick is getting more back than you put in.

But when it comes to real people, the dividends are not so clear. How would you measure your gains, or cash in on your investment? And what would represent a good return?

You might be doubly wary of investing in people if you knew they had been uprooted from their homes, stripped of their livelihoods and possessions, perhaps separated from their families, had lost loved ones, and were having to start their lives all over again.

But in a world of conflict and upheaval, we as an international community are missing out one of the best investments there is: the education of young refugees. This is not an expense, but a golden opportunity.

3.7 million refugee children are out of school

For most of us, education is how we feed curious minds and discover our life’s passions. It is also how we learn to look after ourselves – how to navigate the world of work, to organize our households, to deal with everyday chores and challenges.

For refugees, it is all that and more. It is the surest road to recovering a sense of purpose and dignity after the trauma of displacement. It is – or should be – the route to labour markets and economic self-sufficiency, spelling an end to months or sometimes years of depending on others.

Compared to the trillions of dollars wasted on conflict, and the cost to societies and economies when ordinary civilians are forcibly displaced en masse, this is a no-brainer investment.

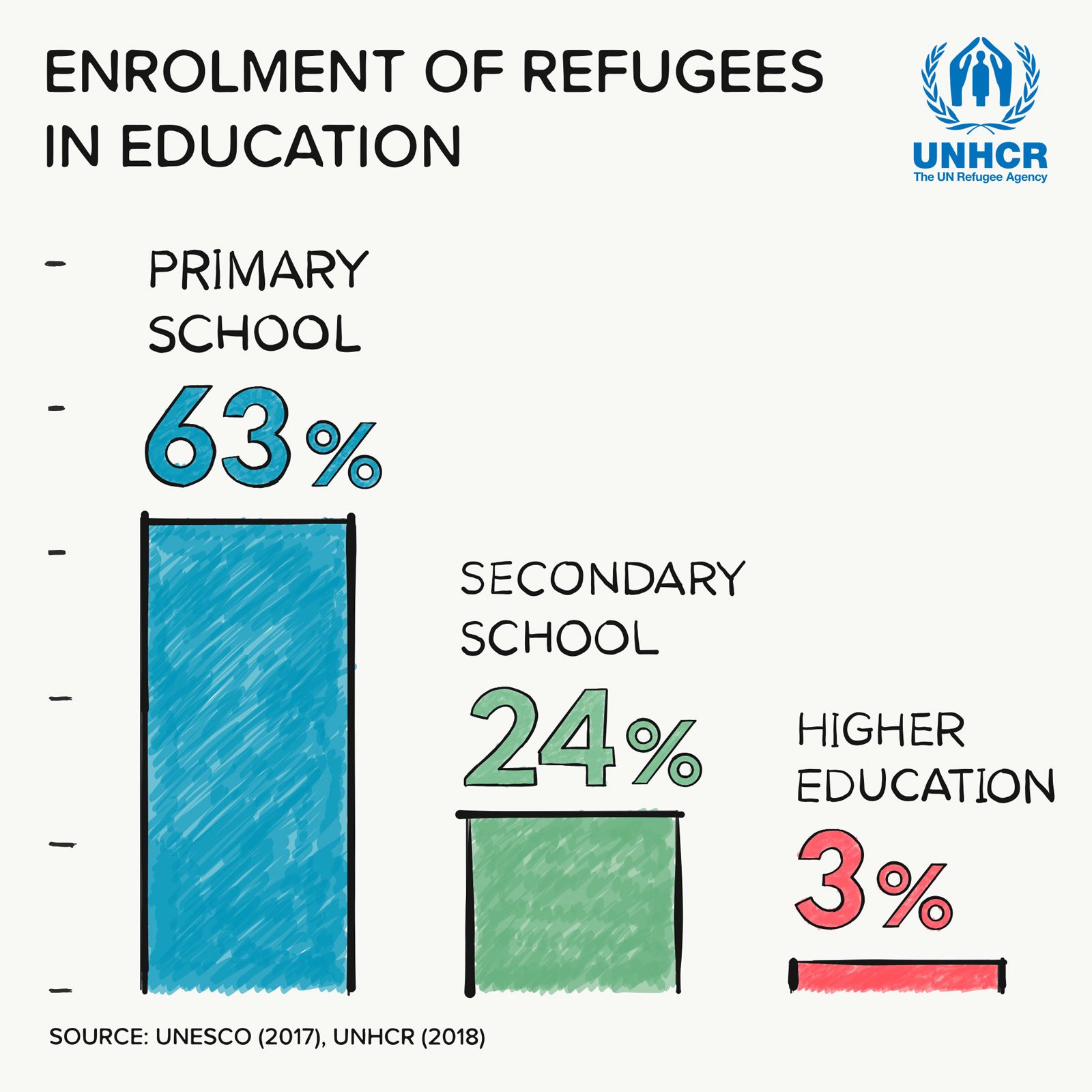

The gains in educational enrolment revealed in this year’s UNHCR report on refugees and education, small as they are in percentage terms, still represent life-changing opportunities for tens of thousands of refugee children, adolescents and youth. Refugee enrolment in primary school is up from 61 to 63 per cent, while secondary level enrolment has risen from 23 to 24 per cent. I particularly welcome the increase in numbers of refugees accessing higher education – a rise to 3 per cent after several years stuck at 1 per cent.

Higher-level education turns students into leaders. It harnesses the creativity, energy and idealism of refugee youth and young adults, casting them in the mould of role models, developing critical skills for decision-making, amplifying their voices and enabling rapid generational change.

The gains in primary and higher education cannot mask the huge shortfall in places and the yawning gap in opportunity, especially at secondary level. The proportion of refugees enrolled in secondary education is more than two-thirds lower than the level for non-refugees – 24 per cent, compared to the global rate of 84 per cent.

Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, with pupils at Al Shuhada School in Souran, Syria, where UNHCR is assisting former refugees and displaced people who have returned home. © UNHCR/ANDREW MCCONNELL

The effect is devastating. Without the stepping stone of secondary school, progress made over the past year will be short-lived, and the futures of millions of refugee children will be thrown away.

Young refugees such as Gift, a South Sudanese boy now living in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, who was so determined to go to school that he learned French and constructed his own solar-powered light to study after dark. His hopes of progressing to secondary level are likely to be dashed because there is quite simply no school in his area for him to attend.

Young refugees such as Hina, who excelled at primary school in Pakistan but found that, out of 500 places at the secondary school in Peshawar she wanted to attend, only one of them was for a refugee.

I myself have seen the same phenomenon in Bangladesh: refugee children still unable to join official schools and follow a recognized curriculum. It is a profoundly dispiriting situation.

Young students read in a girl-only room at Paysannat L school in Mahama refugee camp, Rwanda. The school welcomes around 20,000 children. Eighty per cent are Burundian refugees and the rest come from the host community. © UNHCR/GEORGINA GOODWIN

This failure to improve the provision of secondary education for refugees does not just kick away the ladder to higher, technical and vocational education and training. As well as its countless other benefits, education is fundamentally protective. Children in school are less likely to be involved in child labour or criminal activity, or to come under the influence of gangs and militias. Girls are less likely to be coerced into early marriage and pregnancy, and can study and socialize in safe spaces.

Schools should be safe havens. That is why we must all condemn the acts of violence against schools, pupils and teachers that continue to be carried out in countries affected by conflict. According to the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, there were 14,000 such incidents in 34 countries between 2014 and 2018, including bombings, partial or total occupation by armed groups, abduction, rape and forced recruitment. Such unpardonable violence against innocents must stop.

Furthermore, without ensuring access to an inclusive secondary education, the international community will fail to meet several of the Sustainable Development Goals – not just SDG4, which is to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, but also commitments to eradicating poverty, promoting decent work and reducing inequality.

Safia Ibrahimkel, 24, is an Afghan refugee living in Peshawar, Pakistan. As a member of UNHCR’s Global Youth Advisory Council, she attended a workshop in Berlin on forming a new tertiary education student network. © UNHCR/GORDON WELTERS

That is why UNHCR places such importance on the inclusion of refugee children in national education systems, leading to recognized qualifications and certification. This creates conditions in which refugee children and youth can learn, thrive and develop their potential in peaceful coexistence with each other, and with local children. In a world in which conflict appears to come more easily than peace, these are invaluable lessons.

Investing in a refugee’s education is a collective endeavour with collective rewards, requiring the involvement of all levels of society to make the biggest gains. Governments, business, educational institutions and non-governmental organizations must unite to improve the provision of education at all levels, particularly secondary, and to allow refugees the same access as host-country citizens. Our ambition over the next decade, set out in UNHCR’s Refugee Education 2030 strategy, is to have refugees achieving parity with their non-refugee peers in pre-primary, primary and secondary education, and to boost enrolment in higher education to 15 per cent.

I am therefore proud to announce a new initiative to improve secondary education opportunities for refugees. After pilot projects in Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Pakistan since 2017, the initiative will ambitiously expand over the coming years with a focus on investing in teachers and schools, community schemes to encourage enrolment and financial support for refugee families. This programme is aimed not just at refugees but the community at large, so that all children will benefit from new opportunities. By boosting secondary-level enrolment, we aim to get more refugees and host community peers to progress to higher studies. And we hope to show them that a full educational cycle is possible, motivating more of them to come to school and stay there.

It is my hope that at the forthcoming Global Refugee Forum, governments, the private sector, educational organizations and donors will unite to give their backing to this initiative – in the spirit of responsibility-sharing and collaboration that lies at the heart of the Global Compact on Refugees.

These are ambitious targets, but they come with incalculable rewards. Education will prepare refugee children and youth for the world of today and of tomorrow. In turn, it will make that world more resilient, sustainable and peaceful. And that is not a bad return on our investment.