One Night at Sea

A Spanish fisherman made a valiant decision, saving a dozen lives on the Mediterranean.

By Zahra Mackaoui

3 October 2019

One Night at Sea

A Spanish fisherman made a valiant decision, saving a dozen lives on the Mediterranean.

By Zahra Mackaoui

3 October 2019

THE DECISION

Destiny came calling for Pascual Durá one night on his fishing boat 90 nautical miles off the coast of Libya. It came in the form of a life-or-death choice. That was when he discovered he had a compassionate heart – just like his father before him.

It was 22 November 2018, and Pascual was on the deck of the Nuestra Madre Loreto, a Spanish fishing vessel. As captain, he was keeping watch just outside Libyan waters. At 8:35 p.m. he saw lights on the water. Drawing closer, he saw a Libyan coast guard vessel intercepting a rubber Zodiac dinghy packed with people.

Pascual Durá, captain of the Nuestra Madre Loreto.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

When the passengers saw the coast guard, some plunged overboard because they feared being returned to detention in Libya more than they feared the open sea at night.

Pascual could have turned away and carried on fishing. Few would have known. Instead, he cut the engine and threw life jackets and ropes into the water. Amid the darkness and confusion, 12 people clambered aboard, their lives saved.

Pascual Durá, captain of the Nuestra Madre Loreto.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

Pascual Durá, captain of the Nuestra Madre Loreto.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

THE DECISION

Destiny came calling for Pascual Durá one night on his fishing boat 90 nautical miles off the coast of Libya. It came in the form of a life-or-death choice. That was when he discovered he had a compassionate heart – just like his father before him.

It was 22 November 2018, and Pascual was on the deck of the Nuestra Madre Loreto, a Spanish fishing vessel. As captain, he was keeping watch just outside Libyan waters. At 8:35 p.m. he saw lights on the water. Drawing closer, he saw a Libyan coast guard vessel intercepting a rubber Zodiac dinghy packed with people.

When the passengers saw the coast guard, some plunged overboard because they feared being returned to detention in Libya more than they feared the open sea at night.

Pascual could have turned away and carried on fishing. Few would have known. Instead, he cut the engine and threw life jackets and ropes into the water. Amid the darkness and confusion, 12 people clambered aboard, their lives saved.

THE RESCUE

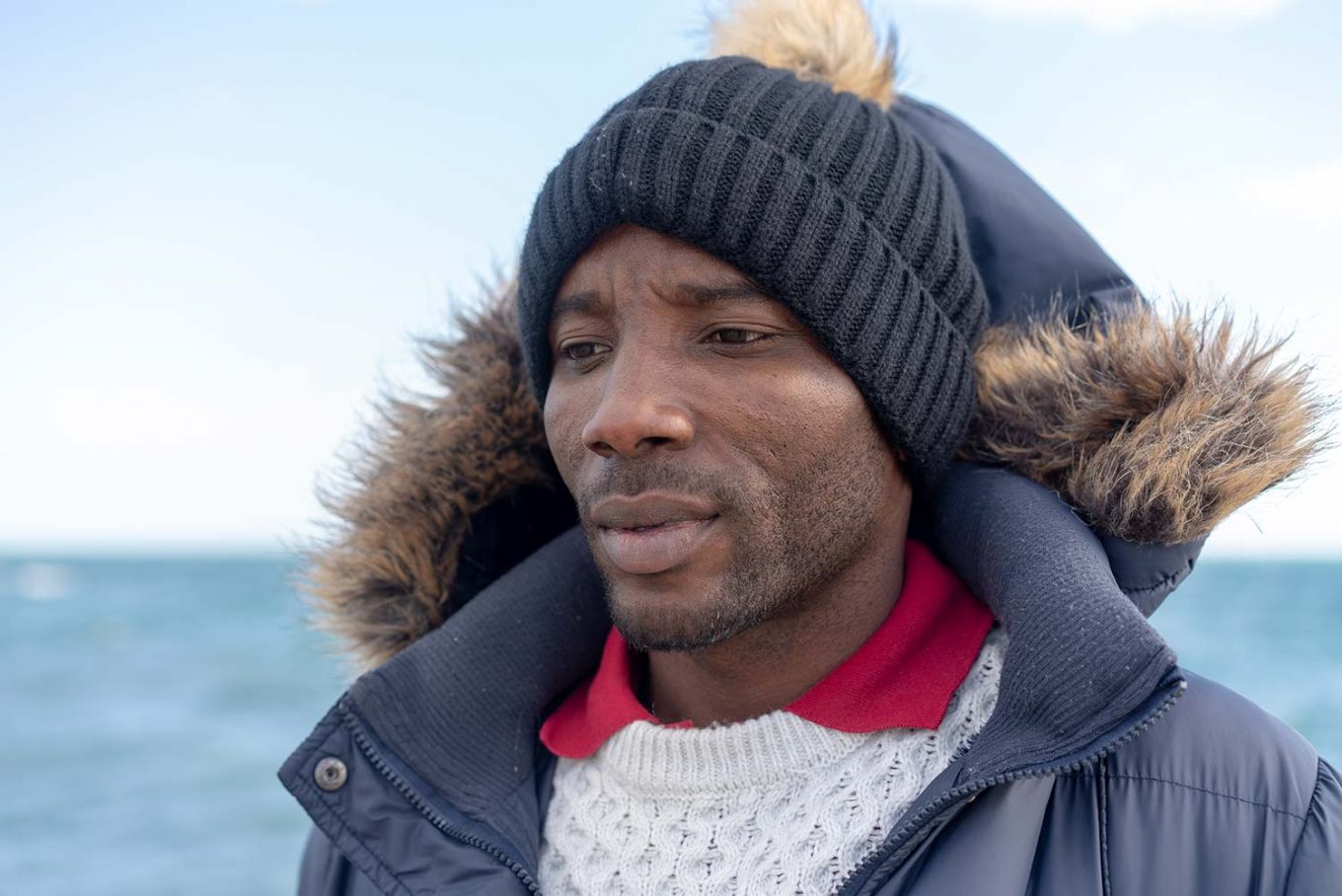

One of them was Frank, a Nigerian man who did not know how to swim.

“I would be dead … if they had not attended to me that night,” he says.

Frank, a Nigerian, rescued by the Nuestra Madre Loreto.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

Frank, a Nigerian, rescued by the Nuestra Madre Loreto.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

THE RESCUE

One of them was Frank, a Nigerian man who did not know how to swim.

“I would be dead … if they had not attended to me that night,” he says.

EUROPE’S REFUGEES

The last few years have seen many tragedies on the Mediterranean, and also many acts of heroism. But as governments have tightened rules on private and charity vessels, rescues like the one Pascual performed are becoming less common.

More than 1,000 people have died or gone missing this year on the Mediterranean, according to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency.

NGO search-and-rescue vessels have faced increasing legal and logistical restrictions on their activities. At different times in the last year, these have led to no NGO boats being at sea available to rescue people in distress.

Aid workers shuttle a group of asylum-seekers to the Phoenix rescue boat on 24 November, 2016. The Phoenix, belonging to humanitarian group Migrant Offshore Aid Station, intercepted the inflatable carrying 146 refugees and migrants who had travelled from West Africa to Libya, and attempted to reach Europe.

© UNHCR/Giuseppe Carotenuto

Aid workers shuttle a group of asylum-seekers to the Phoenix rescue boat on 24 November, 2016. The Phoenix, belonging to humanitarian group Migrant Offshore Aid Station, intercepted the inflatable carrying 146 refugees and migrants who had travelled from West Africa to Libya, and attempted to reach Europe.

© UNHCR/Giuseppe Carotenuto

EUROPE’S REFUGEES

The last few years have seen many tragedies on the Mediterranean, and also many acts of heroism. But as governments have tightened rules on private and charity vessels, rescues like the one Pascual performed are becoming less common.

More than 1,000 people have died or gone missing this year on the Mediterranean, according to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency.

NGO search-and-rescue vessels have faced increasing legal and logistical restrictions on their activities. At different times in the last year, these have led to no NGO boats being at sea available to rescue people in distress.

THE FATHER’S STORY

Valor runs in the Dura family. In 2006 Pascual’s father, Pepe Durá, rescued 51 people off the coast of Malta in 2006, an act commemorated by a small plaque at the entrance to the port in the Spanish town of Santa Pola, where the Durá family live.

“Fishermen are always the gentlemen of the sea,” the plaque reads in part.

Pascual Durá works on board the Nuestra Madre Loreto in the port of Santa Pola near Alicante, Spain.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

As a child, Pascual spent many days and nights aboard the 25-metre-long Nuestra Madre Loreto. He was 16 when his father’s rescue took place. He remembers media coverage during the eight days the boat was stuck at sea, prevented from disembarking.

When the crew were eventually allowed to dock in Spain with the rescued passengers, they were hailed as local heroes and awarded prizes for their courage. By the end of 2007, Durá family boats had carried out two more rescues at sea, bringing the total of people saved to almost 100.

“He set an example … but it is also the natural thing to do,” says Pascual from his home in Santa Pola. “That is what it means to be a human being.”

Pascual Durá works on board the Nuestra Madre Loreto in the port of Santa Pola near Alicante, Spain.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

Pascual Durá works on board the Nuestra Madre Loreto in the port of Santa Pola near Alicante, Spain. © UNHCR/Markel Redondo

THE FATHER’S STORY

Valor runs in the Dura family. Pascual’s father, Pepe Durá, rescued 51 people off the coast of Malta in 2006, an act commemorated by a small plaque at the entrance to the port in the Spanish town of Santa Pola, where the Durá family live.

“Fishermen are always the gentlemen of the sea,” the plaque reads in part.

As a child, Pascual spent many days and nights aboard the 25-metre-long Nuestra Madre Loreto. He was 16 when his father’s rescue took place. He remembers media coverage during the eight days the boat was stuck at sea, prevented from disembarking.

When the crew were eventually allowed to dock in Spain with the rescued passengers, they were hailed as local heroes and awarded prizes for their courage. By the end of 2007, Durá family boats had carried out two more rescues at sea, bringing the total of people saved to almost 100.

“He set an example … but it is also the natural thing to do,” says Pascual from his home in Santa Pola. “That is what it means to be a human being.”

THE ORDEAL

Until that night last November, Pascual had assumed his family’s story of rescuing refugees and migrants was finished. Once the survivors were on board, he also thought that their ordeal was over. Instead, he faced a new ordeal.

Italy, Malta and Spain initially declined permission for the vessel to disembark its passengers. For 10 days, the Nuestra Madre Loreto was stuck out at sea. With food and fuel running low, and with twice as many people crammed on deck as normal, conditions quickly grew dire.

Back home in Santa Pola, Pascual’s family and the community watched in dismay. They were powerless to intervene. The situation was especially painful for Pepe, who saw history repeating itself – this time with his son at the centre.

“It was hard to see it happening all over again… He wasn’t going to let people die,” Pepe says.

THE RETURN

After ten days aboard Pascual’s fishing boat, the 12 survivors were finally allowed to come ashore in Malta, and then were transferred to Spain. When the Nuestra Madre Loreto returned home to Santa Pola, Pascual and his crew – just like Pepe a dozen years earlier – was celebrated for saving lives at sea.

“Almost the entire town came to receive them,” said Rafael Bonmati, a local restaurant owner. “There was music and drums. The Town Hall thanked him and did a plaque for him.”

“You are never going to leave people alone in the sea like that. You have to rescue them. They are human beings,” Bonmati added.

Video © UNHCR by Zahra Mackaoui, producer / Bela Szandelszky, camera-editor

THE REUNION

Before long, Pascual went out on another fishing expedition, returning to Santa Pola three months later to make needed repairs on his boat. The paint was peeling and oil from a broken winch covered the deck.

Frank and Diop visit Pascual Durá.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

Two of the men he had rescued, Frank from Nigeria and Diop from Senegal, paid him a visit. They had moved to a reception centre in Madrid while their claim for asylum is decided. Their perilous journey and that November night has left scars that made the meeting all the more poignant.

“Seeing him makes me feel … alive, that I have somebody behind me, just like a family … who is willing to help those that are in need,” said Frank.

Frank and Diop visit Pascual Durá.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

Frank and Diop visit Pascual Durá. © UNHCR/Markel Redondo

THE REUNION

Before long, Pascual went out on another fishing expedition, returning to Santa Pola three months later to make needed repairs on his boat. The paint was peeling and oil from a broken winch covered the deck.

Two of the men he had rescued, Frank from Nigeria and Diop from Senegal, paid him a visit. They had moved to a reception centre in Madrid while their claim for asylum is decided. Their perilous journey and that November night has left scars that made the meeting all the more poignant.

“Seeing him makes me feel … alive, that I have somebody behind me, just like a family … who is willing to help those that are in need,” said Frank.

BACK TO SEA

When the repairs were done, Pascual prepared to set out again for another three-month stretch at sea. The last few days on land were the hardest, as he said goodbye to family and worried about whether or not he would break even on the next catch. He was also concerned that he could encounter more people stranded at sea, forcing him into a fresh ordeal. Still, his mind was made up.

“If it happened again, of course, I would do the same a thousand times over.”

A crew member works on the Nuestra Madre Loreto.

© UNHCR/Markel Redondo

A crew member works on the Nuestra Madre Loreto. © UNHCR/Markel Redondo

BACK TO SEA

When the repairs were done, Pascual prepared to set out again for another three-month stretch at sea. The last few days on land were the hardest, as he said goodbye to family and worried about whether or not he would break even on the next catch. He was also concerned that he could encounter more people stranded at sea, forcing him into a fresh ordeal. Still, his mind was made up.

“If it happened again, of course, I would do the same a thousand times over.”