COLOMBIA. Venezuelans risk life and limb to seek help in Colombia. A father carries his young daughter through treacherous, muddy scrublands by the banks of the Tachira River, which forms the border between Venezuela and Colombia. In a context of rampant hyperinflation, food shortages, political turmoil, violence and persecution, more than 3 million Venezuelans have fled the country, making such perilous journeys in search of safety. © UNHCR/Vincent Tremeau

Every minute in 2018,

25 people were forced to flee

“What we are seeing in these figures is further confirmation of a longer-term rising trend in the number of people needing safety from war, conflict and persecution.”

The Global Trends Report is published every year to analyze the changes in UNHCR’s populations of concern and deepen public understanding of ongoing crises. UNHCR counts and tracks the numbers of refugees, internally displaced people, people who have returned to their countries or areas of origin, asylum-seekers, stateless people and other populations of concern to UNHCR. These data are kept up to date and analyzed in terms of various criteria, such as where people are, their age and whether they are male or female. This process is extremely important in order to meet the needs of refugees and other populations of concern across the world and the data help organizations and States to plan their humanitarian response.

Chapters: Trends at a glance | Introduction | Refugees | Focus on: Protracted refugee situations | Case Study: The Venezuela Situation | Helping to provide solutions | Internally Displaced People (IDPs) | Asylum-Seekers | Focus on: Unaccompanied and separated children | Stateless People | Other Groups or People of Concern | Special section: Urban refugees | Demographic and Location Data |

2018 in Review

TRENDS AT A GLANCE

The global population of forcibly displaced increased by 2.3 million people in 2018. By the end of the year, almost 70.8 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations. As a result, the world’s forcibly displaced population remained yet again at a record high.

70.8 MILLION

FORCIBLY DISPLACED WORLDWIDE

as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations at end-2018

- 25.9 million refugees

- 20.4 million refugees under UNHCR’s mandate

- 5.5 million Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate

- 41.3 million internally displaced people

- 3.5 million asylum-seekers

13.6

MILLION NEWLY DISPLACED

An estimated 13.6 million people were newly displaced due to conflict or persecution in 2018.

This included 10.8 million individuals displaced2 within the borders of their own country and 2.8 million new refugees and new asylum-seekers.

37,000

NEW DISPLACEMENTS EVERY DAY

The number of new displacements was equivalent to an average of 37,000 people being forced to flee their homes every day in 2018.

4 IN 5

Nearly 4 out of every 5 refugees lived in countries neighbouring their countries of origin.

16%

Countries in developed regions hosted 16 per cent of refugees, while one third of the global refugee population (6.7 million people) were in the Least Developed Countries.

3.5

MILLION ASYLUM-SEEKERS

By the end of 2018, about 3.5 million people were awaiting a decision on their application for asylum.

2.9

MILLION DISPLACED PEOPLE RETURNED

During 2018, 2.9 million displaced people returned to their areas or countries of origin, including 2.3 million IDPs and nearly 600,000 refugees. Returns have not kept pace with the rate of new displacements.

1.7

MILLION NEW CLAIMS

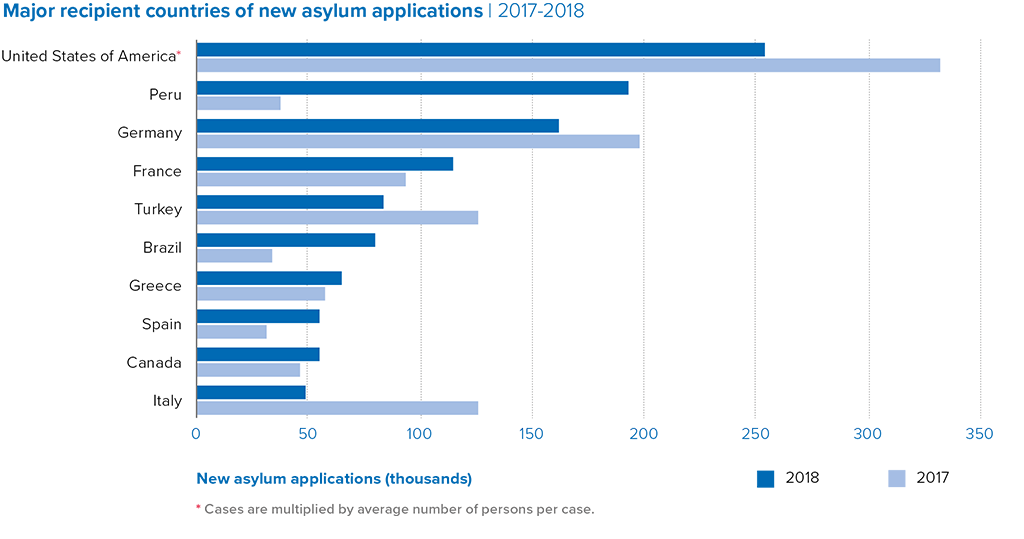

Asylum-seekers submitted 1.7 million new claims. With 254,300 such claims, the United States of America was the world’s largest recipient of new individual applications, followed by Peru (192,500) Germany (161,900), France (114,500) and Turkey (83,800).

81,300

REFUGEES FOR RESETTLEMENT

In 2018, UNHCR submitted 81,300 refugees to States for resettlement. According to government statistics, 25 countries admitted 92,400 refugees for resettlement during the year, with or without UNHCR’s assistance.

138,600

UNACCOMPANIED OR SEPARATED CHILDREN

Some 27,600 unaccompanied and separated children sought asylum on an individual basis and a total of 111,000 unaccompanied and separated child refugees were reported in 2018. Both numbers are considered significant underestimates.

67%

FROM FIVE COUNTRIES

Altogether, more than two thirds (67 per cent) of all refugees worldwide came from just five countries:

- Syrian Arab Republic (6.7 million)

- Afghanistan (2.7 million)

- South Sudan (2.3 million)

- Myanmar (1.1 million)

- Somalia (0.9 million)

3.7

MILLION PEOPLE

For the fifth consecutive year, Turkey hosted the largest number of refugees worldwide, with 3.7 million people. The main countries of asylum for refugees were:

- Turkey (3.7 million)

- Pakistan (1.4 million)

- Uganda (1.2 million)

- Sudan (1.1 million)

- Germany (1.1 million)

1/2

CHILDREN

Children below 18 years of age constituted about half of the refugee population in 2018, up from 41 per cent in 2009 but similar to the previous few years

VENEZUELA

Venezuelan refugees and asylum-seekers grew in number. The broader movement of Venezuelans across the region and beyond increasingly took on the characteristics of a refugee situation, with some 3.4 million outside the country by the end of 2018.

LEBANON

Lebanon continued to host the largest number of refugees relative to its national population, where 1 in 6 people was a refugee. Jordan (1 in 14) and Turkey (1 in 22) ranked second and third, respectively.

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

BRAZIL. A Venezuelan girl in silhouette is captured by photo as the sun sets on refugee shelters around her. The photo was taken at the National Geographic Photo Camp, an initiative which teaches youths from refugee and at-risk communities how to use photography to tell their stories. © UNHCR/Genangely Pinero

The world now has a population of 70.8 million forcibly displaced people.

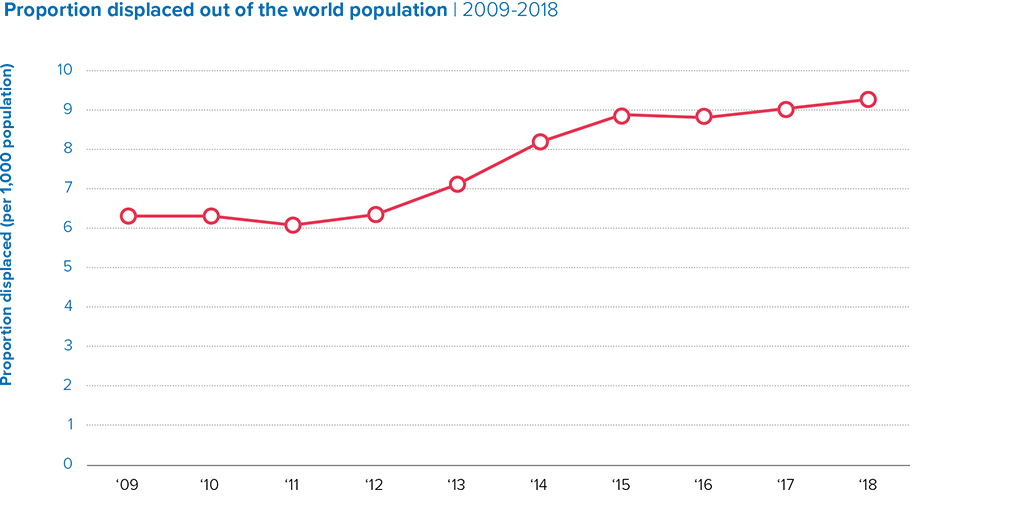

The global population of forcibly displaced people grew substantially from 43.3 million in 2009 to 70.8 million in 2018, reaching a record high. Most of this increase was between 2012 and 2015, driven mainly by the Syrian conflict. But conflicts in other areas also contributed to this rise, including Iraq, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and South Sudan, as well as the massive flow of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar to Bangladesh at the end of 2017.

The refugee population under UNHCR’s mandate has nearly doubled since 2012. In 2018, the increase was driven particularly by internal displacement in Ethiopia and asylum-seekers fleeing Venezuela. The proportion of the world’s population who were displaced also continued to rise, as the world’s forcibly displaced population grew faster than the global population.

13.6 million forced to flee in 2018

Large numbers of people were on the move in 2018. During the year, 13.6 million people were newly displaced, including 2.8 million who sought protection abroad (as new asylum-seekers or newly registered refugees) and 10.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs), who were forced to flee but remained in their own countries. This means that on every day of 2018, an average of 37,000 people were newly displaced. Many returned to their countries or areas of origin to try to rebuild their lives, including 2.3 million IDPs and nearly 600,000 refugees.

Some 1.6 million Ethiopians made up the largest newly displaced population during the year, 98 per cent of them within their country. This increase more than doubled the existing internally displaced population in the country.

Syrians were the next largest newly displaced population, with 889,400 people during 2018. Of these, 632,700 were newly displaced/registered outside the country, while the remainder were internally displaced. Nigeria also had a high number of newly displaced people with 661,800, of which an estimated 581,800 were displaced within the country’s borders.

Most displaced people remained close to home

The vast majority of newly displaced people remained close to home. For example, most Syrians fled to Turkey, where there were half a million new refugee registrations and asylum applications. Most of those forced to flee South Sudan went to Sudan or Uganda, and those displaced from DRC also headed to Uganda.

At the end of 2018, Syrians still made up the largest forcibly displaced population, with 13.0 million people living in displacement, including 6.7 million refugees, 6.2 million internally displaced people (IDPs) and 140,000 asylum-seekers. Colombians were the second largest group, with 8.0 million forcibly displaced, most of them (98 per cent) inside their country at the end of 2018. A total of 5.4 million Congolese from DRC were also forcibly displaced, of whom 4,517,000 were IDPs and 854,000 were refugees or asylum-seekers. Other large displaced populations of IDPs, refugees or asylum-seekers at the end of 2018 were from Afghanistan (5.1 million), South Sudan (4.2 million), Somalia (3.7 million), Ethiopia (2.8 million), Sudan (2.7 million), Nigeria (2.5 million), Iraq (2.4 million) and Yemen (2.2 million).

The situation in Cameroon was complex as it was both a source country and host country of refugees and asylum-seekers, along with multiple internal displacements in 2018. In total, there were 45,100 Cameroonian refugees globally at the end of 2018. Nigeria hosted 100 at the beginning of 2018 compared to 32,800 by the end of the year. This is in addition to 668,500 IDPs. At the same time, Cameroon hosted 380,300 refugees, mainly from the Central African Republic (CAR) and Nigeria.

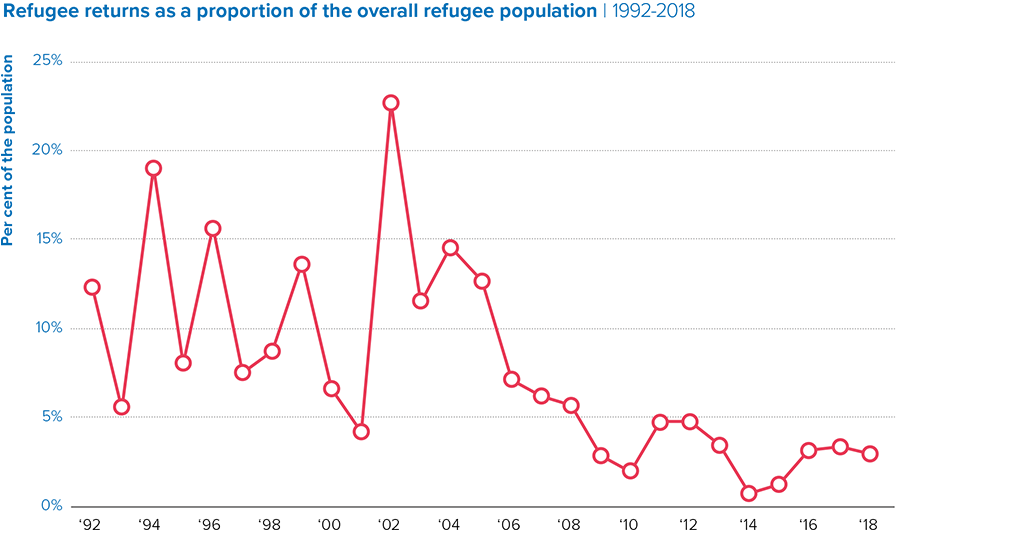

Less than 3% of refugees returned to their country of origin

Returns continued to account for a small proportion of the displaced population and did not offset new displacements. Some 593,800 refugees returned to their countries of origin in 2018 compared with 667,400 in 2017, less than 3 per cent of the refugee population. In addition, 2.3 million IDPs returned in 2018, compared with 4.2 million in 2017. Resettlement provided a solution for close to 92,400 refugees.

As the displaced population continues to grow, steps are taken to further improve data

In 2018, the Expert Group on Refugee and IDP Statistics (EGRIS) presented the results of its work at the 49th session of the UN Statistical Commission. EGRIS is an expert group of about 70 members from country, regional and international level, tasked with addressing challenges associated with working with statistics on refugees, asylum-seekers and IDPs.

The Commission:

- endorsed the International Recommendations on Refugee Statistics;

- endorsed the Technical Report on Statistics of IDPs and supported the proposal to upgrade this work to develop formal recommendations; and

- reaffirmed the mandate to develop a compiler’s manual on refugee and IDP statistics to provide hands-on guidance for the recommendations.

CHAPTER 2

Refugees

IRAQ. Syrian refugee Ronia lives with her five daughters in Domiz refugee camp, northern Iraq. Ronia’s husband died two years ago, leaving her to raise her children alone. © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

Refugees are people fleeing conflict or persecution. They are defined and protected in international law, and must not be expelled or returned to situations where their life and freedom are at risk.

The number of refugees under UNHCR’s care is almost double that of 2012, with two thirds coming from just 5 countries

The total global refugee population is now at the highest level ever recorded – 25.9 million at the end of 2018, including 5.5 million Palestinian refugees under UNRWA’s mandate.

The refugee population under UNHCR’s mandate (the focus of this report) is 20.4 million and has nearly doubled since 2012 when it stood at 10.5 million. Over the course of 2018, this population increased by about 417,100 or 2 per cent – the seventh consecutive year of increase but the smallest rise since 2013.

Notable changes included:

- 7 per cent increase in West Africa.

- The proportion of all refugees under UNHCR’s mandate hosted in Turkey alone increased to 18 per cent.

Origins of refugees

As in 2017, over two thirds of the world’s refugees come from just five countries: Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar and Somalia. As has been the case since 2014, the main country of origin for refugees in 2018 was Syria, with 6.7 million at the end of the year, an increase over the 6.3 million from a year earlier. These refugees were hosted by 127 countries on six continents, however the vast majority (85 per cent) remained in countries in the region. Turkey continued to host the largest population of Syrian refugees, 3.6 million by the end of the year. Countries in the Middle East and North Africa with significant numbers of Syrian refugees included Lebanon (944,200), Jordan (676,300) and Iraq (252,500). Outside the region, countries with large Syrian refugee populations included Germany (532,100), Sweden (109,300) and Sudan (93,500).

Refugees from Afghanistan were the second largest group by country of origin, in what has remained a significant population since the 1980s. At the end of 2018, there were 2.7 million Afghan refugees, mainly in Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran, who between them hosted 88 per cent.

South Sudan remained the third most common country of origin and neighbouring countries hosted almost all refugees originating from there. Of 2.3 million South Sudanese refugees most were in Sudan (852,100), followed by Uganda (788,800) Ethiopia (422,100), Kenya (115,200) and DRC (95,700).

The refugee population from Myanmar, the fourth largest population group by country of origin, remained stable at 1.1 million. Most refugees from Myanmar were hosted by Bangladesh (906,600). Other countries with sizable populations of refugees from Myanmar were Malaysia (114,200), Thailand (97,600) and India (18,800).

The number of Somali refugees worldwide continued to decline slowly, and 80 per cent remained in countries close to Somalia. At the end of 2018, there were 949,700 Somali refugees. Ethiopia was the largest host of Somali refugees with 257,200 at the end of 2018. This was followed by Kenya (252,500) and Yemen (249,000).

The number of refugees originating from Sudan reached 724,800 by the end of 2018, up from 694,600 the previous year, again mostly in neighbouring countries. Chad continued to host the largest Sudanese refugee population with 336,700, while 269,900 Sudanese refugees were living in South Sudan.

At the year’s end, DRC was the seventh largest country of origin of refugees, with 720,300 refugees. As in 2017, CAR remained the country of origin of the eighth largest refugee population. Violence continued to force people to flee, with refugee numbers increasing from 545,500 to 590,900 during 2018. Eritrea remained the ninth largest country of origin with 507,300 refugees at the end of 2018, a slight increase from end-2017 when this population stood at 486,200. Most were in neighbouring countries, such as Ethiopia and Sudan. The number of refugees from Burundi, the tenth largest refugee-producing country, decreased during 2018 from 439,300 at the start of the year to 387,900 at the end. The decrease was mainly due to returns (45,500) and as a result of verification exercises that often reflect spontaneous departures. Nearly all of these refugees (98 per cent) were located in countries in the region, such as Tanzania, Rwanda and DRC.

Host Countries

As has been the case since 2014, Turkey was the country hosting the largest refugee population, with 3.7 million at the end of 2018, up from 3.5 million in December 2017. More than 98 per cent of the refugees in Turkey were from Syria with 3.6 million making up more than 98 per cent of the entire refugee population.

At the end of 2018, Pakistan hosted the second largest refugee population with 1.4 million refugees, almost exclusively from Afghanistan. Uganda continued to host a large refugee population, numbering 1.2 million at the end of 2018. Uganda was host to refugee populations from several countries, the largest being from South Sudan (with 788,800 at the end of 2018). The refugee population in Sudan increased by about 19 per cent over the course of 2018 to just over 1 million, with Sudan becoming the country with the fourth largest refugee population.

During 2018, the refugee population in Germany continued to increase, numbering 1,063,800 at the end of the year. More than half were from Syria (532,100), while other countries of origin included Iraq (136,500) and Afghanistan (126,000).

The registered refugee population in the Islamic Republic of Iran, the sixth largest refugee-hosting country, remained unchanged at 979,400 at the end of 2018, mostly from Afghanistan. The refugee population in Lebanon declined slightly, there were nearly 1 million refugees at the end of 2018 (949,700), compared with 998,900 at the end of 2017, mostly from Syria.

Bangladesh continued to host a large population of 906,600 refugees at the end of 2018, almost entirely from Myanmar. The refugee population in Ethiopia, the ninth largest refugee host country, increased during 2018, reaching 903,200, with over half from South Sudan (422,100).

Jordan experienced a slight increase in its refugee population, providing protection to 715,300 people, mostly from Syria, by the end of 2018, up from 691,000 in 2017 and making it the tenth largest refugee-hosting country in the world.

Other countries hosting significant refugee populations at the end of 2018 included DRC (529,100), Chad (451,200), Kenya (421,200), Cameroon (380,300) and France (368,400).

New refugees

During 2018, 1.1 million people were reported as new refugees, down from the 2.7 million reported in 2017. Recognition on a group or prima facie basis was given to 599,300 refugees, and 461,200 were granted some form of temporary protection. Syrians were the largest group of new refugees registered on a group or prima facie basis, accounting for more than half of new registrations mostly in Turkey, although many will have already been present in Turkey for a while before registering.

The conflict in South Sudan continued to displace many, with 179,200 new refugees registered in 2018. However, this was a lower rate of displacement than was seen in the previous year when over 1 million new refugees were recorded. Refugees from DRC constituted the third largest group of new refugees with 123,400 people forcibly displaced across its borders in 2018. Most fled to Uganda (119,900), while smaller numbers of new refugees were registered in Rwanda (2,600) and South Sudan (800).

Other countries of origin of new refugees included CAR (53,100, mainly to Chad and Cameroon), Nigeria (41,000, mainly to Cameroon) and Cameroon (32,600, all to Nigeria).

Turkey was the country of asylum that registered the largest number of new refugees in 2018 with 397,600 Syrians registered under the Government’s Temporary Protection Regulation.

This was followed by Sudan which reported new refugees mainly from South Sudan (99,400) and Syria (81,700). Uganda also registered 160,600 new refugees in 2018, mainly from DRC (119,900). In addition, Cameroon reported 52,800 new refugees, from Nigeria (31,800) and CAR (20,900); Ethiopia reported 42,100 new refugees, mainly from South Sudan (25,400) and Eritrea (14,600); and Nigeria reported 32,600 new arrivals, all from Cameroon.

Measuring the impact on a host country

Comparing the size of a refugee population with that of a host country can help measure the impact of hosting that population. Lebanon, while hosting the seventh largest refugee population, had the highest refugee population relative to national population with 156 refugees per 1,000 national population. Similarly, Jordan hosted the tenth largest refugee population but the second largest relative to national population with 72 refugees per 1,000. These figures relate only to the refugee population under UNHCR’s mandate, and Lebanon and Jordan respectively hosted an additional half a million and 2.2 million Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate.

Turkey hosted the third largest refugee population relative to its national population with 45 refugees per 1,000. Half of the ten countries with the highest refugee population relative to national population were in sub-Saharan Africa. In high-income countries, there are, on average, just 2.7 refugees per 1,000 national population, but this figure is more than doubled in middle- and low-income countries, with 5.8 refugees per 1,000.

Refugees are people fleeing conflict or persecution. They are defined and protected in international law, and must not be expelled or returned to situations where their life and freedom are at risk.

FOCUS ON

Protracted, long-term refugee situations

SUDAN. Eritrean refugee Sherifa, 35, participates in UNHCR’s campaign against human trafficking at Shagarab refugee camp in Sudan. Sherifa, whose husband went missing, holds up a sign saying: “I need freedom and peace”. © UNHCR/Hussein Eri

UNHCR defines a protracted refugee situation as one in which 25,000 or more refugees from the same nationality have been in exile for five consecutive years or more in a given host country. The definition has limitations, because the refugee situation is constantly changing in each situation with new arrivals and returns. If a protracted refugee situation has been going on for 20 years it doesn’t mean that it has been stable throughout that time, or that all the refugees have been there for that long.

78 per cent of all refugees are in protracted refugee situations

15.9 million refugees were in protracted situations at the end of 2018. This represented 78 per cent of all refugees, compared with 66 per cent the previous year. 10.1 million refugees were in protracted situations of less than 20 years, more than half represented by the displacement situation of Syrians in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. 5.8 million were in a situation lasting 20 years or more, dominated especially by the 2.4 million Afghan refugees in the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan where the displacement situation has lasted for 40 years.

Nine new protracted refugee situations

In 2018, nine situations were newly classed as protracted, as they reached the five year mark – South Sudanese refugees in Kenya, Sudan and Uganda; Nigerians in Cameroon and Niger; refugees from DRC and Somalia in South Africa; Pakistani refugees in Afghanistan; and Ukrainian refugees in Russian Federation.

CASE STUDY

The Venezuela Situation

ECUADOR. César and Yoheglith fled Venezuela with their three kids in October 2018. Living in Ibarra, Ecuador, they all sleep in one room. It’s cramped and cold at night, but they feel safe now and are integrating into work and school. © UNHCR/Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo

People are leaving Venezuela for many reasons including violence, shortages of food and medicine, and being unable to support themselves and their families.

By the end of 2018, more than 3 million Venezuelans had left their homes, travelling mainly towards Latin America and the Caribbean. It is one of the biggest displacement crises in the world and the biggest exodus in the region’s recent history. Asylum procedures in the region are overwhelmed, and to date only 21,000 Venezuelans have been recognized as refugees out of 460,000 who have sought asylum, 350,000 in 2018 alone.

Latin American countries had granted an estimated 1 million residence permits and other forms of legal stay to Venezuelans by the end of 2018, allowing access to some basic services. However, a considerable number of Venezuelans were likely to be in an irregular situation, vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. With some 5,000 people leaving Venezuela every day, it is estimated that by the end of 2019 5 million people could have left the country since the beginning of the crisis, heading for Colombia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Peru. Others take dangerous boat journeys to Caribbean islands. Intermittent border restrictions are causing Venezuelans fleeing to neighbouring countries to rely on dangerous routes, exposing them to risks such as sexual exploitation and kidnapping.

Various interconnected factors are causing Venezuelans to leave and it is clear that international protection considerations, according to the refugee criteria in the 1951 Convention/1967 Protocol and the 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, are applicable to the majority of Venezuelans.

Many host countries have shown commendable solidarity towards Venezuelans arriving on their territory, giving them protection and assistance. Through the Quito process, they have cooperated to harmonize their protection responses for Venezuelan nationals and facilitate their legal, social and economic inclusion. In the face of huge numbers of displacements yet to come, only a coordinated and comprehensive approach by governments and humanitarian and development actors, supported by a well-funded international response, will enable the region to cope with the full scale of the crisis.

“When my nine-month-old daughter died because of the lack of medicines, doctors or treatment, I decided to take my family out of Venezuela before another one of my children died. Diseases were getting stronger than us. I told myself, either we leave or we die.”

CHAPTER 3

Helping to provide solutions

AFGHANISTAN. Sadiq is an Afghan returnee who had been living in Pakistan. He now lives in Dasht-e Tarakhi, an informal settlement on the outskirts of Kabul which is mostly populated by returnees from Pakistan. UNHCR and its partners are helping returnees gain access to basic services, land and jobs. © UNHCR/Jim Huylebroek

Every year some refugees agree to return to their country of origin. This process is known as voluntary repatriation. Other options are to take the opportunity to settle in a third country or integrate into the host community.

Lasting solutions so displaced people can rebuild their lives

Finding durable solutions to enable millions of displaced people around the world to rebuild their lives in dignity and safety is a core part of UNHCR’s work. The Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework is part of the Global Compact on Refugees, an agreement for shared responsibility between UNHCR, governments and other organizations. In recent decades, it has become less straightforward to rely on the traditional solutions – voluntary repatriation, local integration or resettlement in third countries. To address this need, the new Framework includes additional measures such as expanding access to resettlement, other complementary pathways, and proactively fostering good conditions for voluntary repatriation.

Returning home under safe conditions – the lasting solution of choice

During 2018, the number of refugees who returned to their countries of origin stood at 593,800, a decline from 2017. Voluntary repatriation remains the preferred lasting solution for the largest number of refugees and requires appropriate measures to ensure that this choice is made freely, without outside pressure. The choice to return must be based on accurate information about the conditions to be expected on arrival in the country of origin.

Over the years, UNHCR has worked with States to enable millions of refugees to return home, through:

- voluntary repatriation programmes,

- small-scale and individual repatriations, and

- ensuring that returns were sustainable.

In 2018, UNHCR observed a number of self-organized returns, sometimes under pressure, to areas where circumstances were partially improving but where peace and security were not fully established. For returns to be sustainable, it is critical they are not rushed and that the conditions for sustainable reintegration are met. However, all individuals have the right to make a personal decision to return voluntarily to their country of origin. When this happens, UNHCR monitors the progress of returns while also advocating for improved conditions.

Data show refugee returns to 37 countries of origin from 62 former countries of asylum during 2018. Data do not show whether these returns were safe, organized and sustainable.

The largest number of returning displaced people headed for Syria

UNHCR has not yet prompted or facilitated returns to Syria because safe, dignified large-scale repatriation cannot be guaranteed. There are significant risks for refugees returning too early and a premature, large-scale return could even further destabilize the region. Despite this, the largest number of returning refugees were headed for Syria, with most of the 210,900 refugees returning from Turkey and smaller numbers from Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan. A Perception and Intentions Survey conducted among Syrian refugees in 2018 showed that 76 per cent of Syrian refugees hoped to return to Syria one day.

The second largest number of refugee returns in 2018 was reported by South Sudan, with 136,200, mostly returning from Uganda (83,600), followed by Ethiopia (40,200). As in the case of Syria, UNHCR did not facilitate or promote refugee returns to South Sudan in 2018. However, UNHCR did seek to monitor and assist the situations of returned refugees and IDPs within the country.

Resettlement – a life-saving tool

Resettlement in a new country that is neither the country of origin, nor the country of asylum, remains a life-saving tool to ensure the protection of those refugees most at risk. As one of the key objectives of the Global Compact on Refugees, resettlement and complementary pathways are also mechanisms for governments and communities across the world to:

- share responsibility for responding to increasingly frequent forced displacement crises, and

- help reduce the impact of large refugee situations on host countries.

UNHCR estimated that 1.4 million refugees were in need of resettlement. However, only 81,300 places for new submissions were provided in 2018. The gap between needs and actual resettlement places continued to grow.

Of the 81,300 submissions made in 2018, 68 per cent were for survivors of violence and torture, those with legal and physical protection needs, and particularly vulnerable women and girls. Just over half of all resettlement submissions concerned children.

Based on official government statistics provided to UNHCR, 92,400 refugees were resettled to 25 countries during 2018 including: Canada (28,100), The United States of America (22,900), Australia (12,700), United Kingdom (5,800) and France (5,600).

Local integration – a positive outcome that is hard to track

One durable solution is the local integration of refugees, a complex, gradual process in which refugees move towards permanent residence rights and, in many cases, citizenship in the country of asylum. Legal, economic, social, and cultural aspects of local integration are also part of the process.

Naturalization – the legal act or process by which a non-citizen in a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country – is used as a measure of local integration. However, it is difficult to distinguish between the naturalization of refugees and non-refugees, so the data do not give an accurate picture of the extent to which refugees are naturalized.

During 2018, a total of 62,600 refugee naturalizations were reported – lower than the 73,400 reported in 2017 – with 27 countries reporting at least one. Turkey reported the most naturalizations with 29,000 in 2018, all originating from Syria. Canada reported the second largest number, with 18,300 from 162 countries. Other countries reporting a significant number of naturalizations were The Netherlands (7,900), Guinea-Bissau (3,500) and France (3,300).

Every year some refugees agree to return to their country of origin. This process is known as voluntary repatriation. Other options are to take the opportunity to settle in a third country or integrate into the host community.

CHAPTER 4

Internally Displaced People (IDPs)

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO. Prosper, 25, fled his village in 2016 after receiving threats from an armed group. He lives with his wife, their three-year-old daughter, and a 12-year-old boy who joined them during their flight. Prosper explains how, unable to find the boy’s parents, they decided to take him in. © UNHCR/Ley Uwera

IDPs are people who have been forced to flee their home but stay within their own country and remain under the protection of their government. They often move to areas where it is difficult for UNHCR to deliver humanitarian assistance and as a result, these people are among the most vulnerable in the world.

Forced to flee within the same country

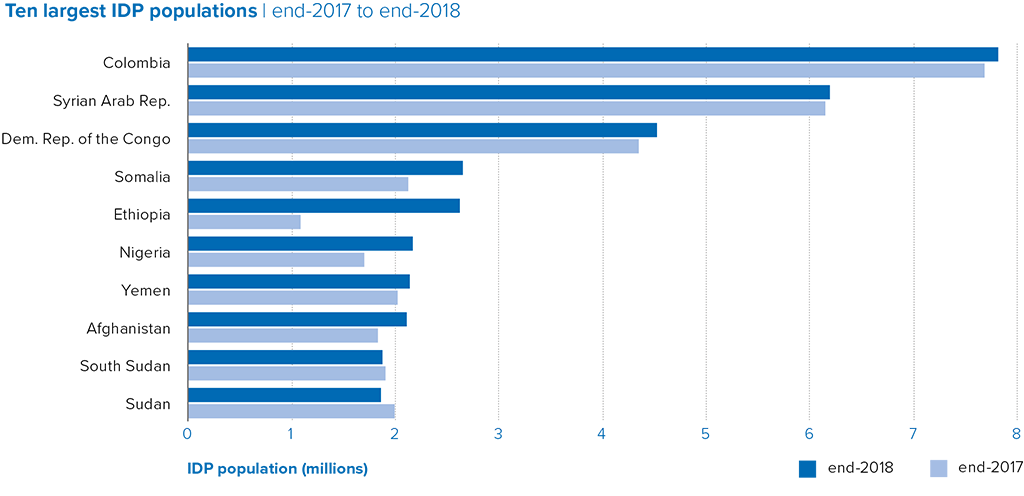

As a consequence of armed conflict, generalized violence and human rights violations, by the end of 2018 some 41.3 million people were displaced within their own countries. This is an increase of 1.3 million compared with 2017 and the largest ever reported by IDMC.

Colombia reported the highest number of internally displaced people with 7.8 million at the end of 2018 according to Government statistics, up 118,200 on the previous year.

Violence, conflict and political uncertainty drive displacement

Syria remained the country with the second highest level of internal displacement. 256,700 new displacements brought the total displaced population to 2 million, more than half of whom were in Idlib Governorate. As the Syria crisis entered its eighth year, continued hostilities led to large-scale displacement with people fleeing sporadic artillery shelling and infighting.

The IDP population in DRC also continued to increase, rising from 4 million at the end of 2017 to 5 million at the end of 2018. Active conflicts and political uncertainties continued to drive significant displacement. Nevertheless, improved security across some territories in Tanganyika facilitated some spontaneous returns.

IDPs reluctant to return because of issues such as fear of reprisals, food insecurity and lack of services

Somalia experienced a 25 per cent increase in internal displacement with 602,700 new displacements during 2018. That brought the total displaced population to 2.6 million, the world’s fourth largest IDP population. This large scale displacement is spurred on by armed conflict and food insecurity. Many IDPs were reluctant to return due to fear of reprisal and limited availability of social services and livelihood opportunities.

In Ethiopia there was a sharp increase in the internally displaced population, which more than doubled from 1.1 million at the beginning of 2018 to 2.6 million at the end. The internally displaced population also grew in Nigeria, where an increase of 27 per cent brought the total IDP population to million. 176,200 returns failed to balance out 581,700 new displacements.

People return to find a home still ravaged by conflict

In Yemen, high levels of movement are masked by the relatively small increase in the internally displaced population, which reached 1 million at the end of 2018. There were 264,300 new displacements and 133,600 returns. However, those returning to their localities of origin often find the area is still affected by conflict and they continue to have significant humanitarian needs.

In Afghanistan the internally displaced population stood at 2.1 million, up from 1.8 million at the end of 2017. There were new displacements and returns throughout the year, often occurring simultaneously in the same province. With two thirds of the population living in areas directly affected by conflict, population movement has become a permanent feature.

In South Sudan the numbers of internally displaced remained high, around 1.9 million, although slightly decreased from the previous year. South Sudan’s recently revitalized peace process offers new opportunities amid de-escalating tensions.

Many IDPs have lived in displacement for more than a decade

At the end of 2018, the internally displaced population in Sudan stood at 1.9 million, a decrease from the 2.0 million at the start of the year. The vast majority of IDPs were in Darfur (88 per cent), where some have been living in long-term displacement for over a decade.

The number of IDPs in Iraq declined over the course of 2018 from 2.6 million to 1.8 million, due to almost 1 million returns. Ninewa Province, which includes the city of Mosul, maintained the largest IDP population at 576,000, despite 437,000 returns during the year. The safe return of displaced people remained an overarching priority.

1.5 million people were registered as internally displaced with the Ukrainian authorities and Cameroon experienced a trebling of its internally displaced population from 221,700 at the start of 2018 to 668,500 at the end. Other countries that reported significant IDP populations included CAR (641,000), Azerbaijan (620,400), Myanmar (370,300) and Georgia (282,400).

5.4 million people became IDPs in 2018

According to data reported by UNHCR offices, over the course of 2018, some 5.4 million people became IDPs, having been forced to move within their countries due to conflict and violence. This is a significant reduction compared with 2017 (8.5 million) but is similar to 2016 (4.9 million).

The substantial increase of over 1.5 million internally displaced people in Ethiopia was mainly the result of inter-communal violence in various pockets of the country over territory, pasture and water rights. Other countries with high levels of new internal displacement included Somalia (602,700), Nigeria (581,700) and Cameroon (514,500).

As in previous years, Iraq continued to have the highest number of returns in 2018 with close to 1 million people (945,000) returning to their localities of origin. This was followed by the Philippines (445,700), CAR (306,200) and Nigeria (176,200).

IDPs are people who have been forced to flee their home but stay within their own country and remain under the protection of their government. They often move to areas where it is difficult for UNHCR to deliver humanitarian assistance and as a result, these people are among the most vulnerable in the world.

CHAPTER 5

Asylum-Seekers

GREECE. Children play with a kitten at the transit site located above a fishing village in northern Lesvos. In September 2018, the reception and identification centre in Moria, on the island of Lesvos, hosted more than 8,500 asylum-seekers, almost four times its official capacity. Some 35,000 refugees and migrants arrived in Greece between January and September 2018 – an increase of 48 per cent compared to 2017. © UNHCR/Daphne Tolis

Asylum-seekers are people who are seeking sanctuary in a country other than their own and are waiting for a decision about their status

1 in 5 asylum-seekers come from Venezuela

Some 2.1 million individual applications for asylum or refugee status were submitted to States or UNHCR in 158 countries or territories. This represents a small increase from 2017 when there were 1.9 million.

In the countries where UNHCR managed refugee status determination 227,800 applications were registered in 2018, of which 12,200 were on appeal or repeat.

New individual asylum applications – where were they lodged?

The United States of America

As in 2017, the United States of America received the most new asylum applications, with 254,300 registered during 2018 from 166 countries or territories. While this was a decrease compared with 2017 (331,700), it was similar to 2016 (262,000). El Salvador was the most common nationality of origin with 33,400 claims. As in 2017, Guatemalans were the next largest group with 33,100 new applications. Venezuelans became the third most common nationality of applicants for asylum in the United States of America during 2018 with 27,500 applications, reflecting the continued deterioration of conditions in Venezuela. This was followed by applicants from Honduras and Mexico. As in previous years, applicants from Central America and Mexico made up about half of all applications (54 per cent). The remaining half of the applications for asylum to the United States of America came from 161 countries.

Peru, Germany and France

As a result of the crisis in Venezuela, the number of asylum applications increased sharply in Peru, which became the second largest recipient of asylum applications globally with 192,500, nearly all submitted by Venezuelans. In 2017, by contrast, Peru received 37,800 asylum claims and 4,400 in 2016.

Germany received 161,900 new asylum applications, continuing a decrease that put them in third place, down considerably from the peak of 722,400 in 2016. As in previous years, Syrians made up the majority with 44,200 asylum claims. Iraqis were the second most common nationality of origin with 16,300 claims in 2018 – a decline from the 21,900 in 2017. The number of applications from Iranians increased in 2018 to 10,900 to become the third most common nationality. Of note is the decrease in new applications from Afghans: While there were 127,000 such applications in 2016, there were only 9,900 in 2018.

The fourth largest recipient of new asylum claims in 2018 was France with 114,500, a 23 per cent increase on 2017. Unlike previous years, applicants from Afghanistan were the most common with 10,300 new applications, compared with 6,600 in 2017. Albanians were the next most common nationality with 8,300 claims.

Turkey, Brazil and Greece

Turkey continued to receive individual asylum claims from nationalities other than Syrians, who receive protection under the Government’s Temporary Protection Regulation. Turkey thus became the fifth largest recipient of new asylum claims with 83,800 submitted in 2018 from Afghanistan, Iraq and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Afghan asylum-seekers continued to submit the most claims in 2018 with 53,000, down slightly from 2017. Similarly, asylum claims from Iraqis remained the second most common and declined from 44,500 in 2017 to 20,000 in 2018. There were also 6,400 claims from Iranians.

Brazil received 80,000 applications in 2018 to become the sixth largest recipient of asylum claims, a considerable rise from 10,300 in 2016. Like Peru, Brazil also witnessed a steep increase in asylum applications from Venezuelans, who accounted for more than three quarters of such claims in 2018 (61,600).

Greece saw a continuation of the trend of increasing new individual asylum claims from 57,000 in 2017 to 65,000 in 2018 (compared with 11,400 in 2015). As in previous years, the most common nationality of origin was still Syrian, although numbers were slowly declining and also representing a decreasing proportion of claims. In contrast, there were increases in claims submitted by Afghans who submitted 11,800 claims in 2018 (7,500 in 2017) and were the second most common nationality of origin.

Spain, Canada and others

During 2018, Spain received 55,700 new asylum claims, the eighth largest number globally and again a significant rise from 31,700 in 2017. There were significant increases in applications from Venezuelans, the most common nationality of origin, and the number of Colombian applicants also more than trebled to 8,800 in 2018.

Canada was the ninth largest recipient of new asylum claims with 55,400 registered in 2018, a small increase on the claims registered in 2017 (47,000), the largest number coming from Nigerian nationals (9,600). Italy was the tenth largest recipient although the number of claims more than halved to 48,900 in 2018. Pakistanis submitted the most applications with 7,300, followed by Nigerians with 5,100 new applications, compared with 25,100 in 2017.

Other countries receiving large numbers of new asylum claims were the United Kingdom (37,500), Mexico (29,600), Australia (28,800) and Costa Rica (28,000).

Where do new asylum-seekers come from?

For the first time, asylum claims from Venezuelans dominated the global asylum statistics with 341,800 new claims in 2018, accounting for more than 1 in 5 claims submitted. In addition to this significantly increased number of new individual claims, an estimated 2.6 million Venezuelans have fled the country but have not applied for asylum, many of whom have international protection needs.

Afghanistan was the next most common country of origin for individual new asylum applications in 2018, with 107,500 claims lodged in 80 countries. As has been the case since 2016, Turkey received the most claims, followed by Greece and France, where numbers of applicants from Afghanistan increased.

Asylum claims from Syrians were the third most common, there were 106,200 new claims in 2018, a quarter of the peak number of 409,900 lodged in 2015. The number of new individual claims is in addition to new arrivals in countries where Syrians receive prima facie or group recognition or temporary protection. This is the case in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. In addition to these countries, individual asylum claims from Syrians were lodged in 98 other countries, mostly in Europe.

The fourth most common country of origin for asylum applications was Iraq with 72,600 new claims in 2018, 20,000 of them in Turkey. This was followed by Germany, which received 16,300 in 2018, down from 21,900 in 2017 and dramatically fewer than the 96,100 received in 2016. Iraqis also applied for asylum 70 other countries.

Similar to the past couple of years, the fifth most common country of origin remained DRC with 61,100 new applications in 2018, in addition to the 123,400 new refugee registrations on a group or prima facie basis. Burundi was the recipient of the largest number of claims with 13,700.

Salvadorans submitted 46,800 new claims globally in 2018, the sixth highest. Most of these were submitted in the United States of America (33,400).

There were 42,000 new asylum claims from Eritreans in 2018, a small decline from the 49,900 in 2017. Israel received the most claims with 6,300, followed by Germany with 5,600.

Hondurans made up the eighth largest group to apply for asylum in 2018 with 41,500 new claims. More than half of these claims were submitted in the United States of America (24,400).

Nigerians were the ninth most common nationality for new asylum-seekers with 39,200 new claims in 2018 about a quarter of which were registered in Germany.

Nationals of Pakistan submitted 35,800 new asylum claims in 2018. Italy received the largest number of these claims with 7,300, followed by Greece (7,200).

Other nationalities that submitted significant numbers of new asylum claims in 2018 included the Islamic Republic of Iran (35,800), Guatemala (34,800), Sudan (32,400) and Nicaragua (31,400).

While these figures give an indicative overview of the situation, the country of origin for some asylum-seekers is unknown, underestimated or undisclosed by some States. Data may include instances of double counting, as some people are likely to have applied for asylum in more than one country. Some countries do not submit asylum data at all.

More asylum-seekers were rejected than were granted protection

Provisional figures indicate that States and UNHCR made 1,134,200 decisions on individual asylum applications – new, on appeal, or repeat – during 2018. These figures do not include cases closed for administrative reasons with no decision issued to applicants, of which 514,900 were reported in 2018.

Available data indicate that 500,100 asylum-seekers were granted protection in 2018, with 351,100 recognized as refugees and 149,000 granted a complementary form of protection. This was the lowest figure since 2013. About 634,100 claims were rejected on substantive grounds, a number that includes negative decisions at the first instance and on appeal.

At the global level (UNHCR and State asylum procedures combined), the Total Protection Rate (TPR) was 44 per cent – i.e. the percentage of substantive decisions that resulted in any form of international protection. This rate is lower than the previous year when it stood at 49 per cent and substantially lower than the 60 per cent reported in 2016.

Looking at the global figures for the countries of origin with over 10,000 substantive decisions, nationals of Burkina Faso had the highest TPR (86 per cent), followed by nationals of DRC (83 per cent), Eritrea (81 per cent), Syria (81 per cent) and Somalia (73 per cent). Just over half of Afghans applications received protection (54 per cent). Venezuelans received protection in under half of decisions (40 per cent) as did Iraqis (46 per cent).

The TPR varies greatly depending on the countries of asylum. For example, Switzerland had a TPR of 75 per cent, compared with Australia and Sweden where only about a quarter of asylum decisions granted protection. Germany made the most substantive decisions (245,700) and had a TPR of 43 per cent.

Millions of people waiting for decisions

There were 3,503,300 asylum-seekers waiting for decisions on pending claims at the end of 2018, 13 per cent more than the previous year. The largest asylum-seeker population at the end of 2018 continued to be in the United States of America (719,000). In Germany the asylum-seeker population continued to reduce, reaching 369,300, a decline of 14 per cent.

Turkey hosted the third largest asylum-seeker population (311,700) not including Syrians who are protected under the country’s Temporary Protection Regulation and do not undergo individual refugee status determination.

Peru has seen a more than six-fold increase of its asylum-seeker population to 230,900 due to the large number of asylum claims from Venezuelans received during the year.

Venezuelans were the nationality with the largest number of pending asylum claims in 2018 with 464,200 cases compared with 148,000 in 2017. Asylum-seekers from Afghanistan constituted the second largest nationality of origin with 310,100 pending claims, followed by Iraqi asylum-seekers (256,700) and asylum-seekers from Syria (139,600) at the end of 2018 Despite improved statistical reporting on pending asylum applications, the actual number of undecided asylum cases is underestimated, as some countries do not report this information.

Asylum-seekers are people who are seeking sanctuary in a country other than their own and are waiting for a decision about their status

FOCUS ON

Unaccompanied and separated children need protection and assistance

Without the protection of family, unaccompanied and separated children are often at risk of exploitation and abuse. Some 138,600 children were in that situation at the end of 2018. Data are essential in order to identify, protect and assist these children and UNHCR is working to improve reporting on this vulnerable population. However, a limited number of countries report on them and the available figures are underestimates Reports show 27,600 such children applied for asylum during 2018. At the end of 2018, 111,000 unaccompanied and separated children were known to be among the refugee population.

Asylum applications from children

In 2018, provisional data indicated that 27,600 unaccompanied or separated children sought asylum on an individual basis in at least 60 countries that report on this figure. While it is known that this is an underestimate, the trend indicates a decline in the number of unaccompanied or separated children applying for asylum, which reflects the overall trends in declining asylum claims since 2015. Most of these claims were from children aged 15 to 17 (18,500) but a substantial minority were from younger children (6,000).

As in previous years, Germany received the most asylum claims from unaccompanied and separated children with 4,100 – substantially lower than the 35,900 in 2016 and 9,100 in 2017.

Other countries that received significant numbers of asylum applications from unaccompanied and separated children included the United Kingdom (2,900), Greece (2,600), Sweden (1,700), Egypt (1,700), Turkey (1,700), Libya (1,500).

As in previous years, the most common country of origin for unaccompanied and separated child asylum applicants was Afghanistan with 4,800 claims – just over half the 8,800 submitted in 2017 and substantially below the 26,700 in 2016. Eritrea continued to be the second most common country of origin with 3,500 claims.

Child refugees

53 countries reported a total of 111,000 unaccompanied and separated child refugees in 2018.

The largest number of unaccompanied and separated child refugees was reported in Uganda with 41,200, with the majority aged under 15 (29,900) and 2,800 aged under 5. Most of these children originated from South Sudan (37,000) and DRC (3,500). Kenya reported 13,200 unaccompanied and separated children in 2018. Other countries with significant such populations included Sudan (11,300), DRC (9,400) and Canada (8,400).

As in 2017, South Sudan was the most common country of origin for unaccompanied and separated child refugees, with 58,600 representing 53 per cent of the global child refugee population. Other countries of origin reported for unaccompanied and separated children included DRC (9,900), Rwanda (7,600) and Syria (7,600).

CHAPTER 6

Stateless People

BANGLADESH. A young Rohingya child is full of smiles as she stands outside a shelter for refugees in Kutupalong camp, Bangladesh. © UNHCR/Roger Arnold

Stateless people are not considered nationals under the law of any state. They may not be able to go to school, see a doctor, get a job, open a bank account, buy a house or even get married. They are also generally not counted or registered in the ways the rest of the population is, meaning their needs are not planned for and their existence not acknowledged.

Finding out how many stateless people there are, and where they live, is the first step towards ending statelessness

There is increased awareness of statelessness globally. States are making an effort, often supported by UNHCR, to identify stateless individuals in their countries. Despite this progress, fewer than half of countries have official statistics on stateless people.

Data on some 3.9 million stateless persons are captured in the Global Trends report, but the true global figure is estimated to be significantly higher. This year UNHCR was able to report on people under UNHCR’s statelessness mandate for 78 countries, but there are other countries where there are reports of stateless populations but no reliable figures.

Prevent and reduce statelessness by recognizing the problem

Identifying stateless people is the first step towards addressing the difficulties they face as well as enabling governments, UNHCR and others to prevent and reduce statelessness. Recognition of statelessness and gathering data about the problem are key elements in UNHCR’s Global Action Plan to end Statelessness, with its accompanying #IBelong campaign. It also calls for the strengthening of civil registration and vital statistics systems and UNHCR, therefore, works with States to undertake targeted surveys and studies. During 2018, a number of new studies were completed, including for Albania, Switzerland and the East African community.

Statistics and information on the situation of stateless populations can also be gathered through population censuses. For this reason, UNHCR works with statisticians and relevant authorities at national level to ensure the inclusion of questions that lead to improved data on stateless populations in the 2020 round of population and housing censuses.

Slow progress

In 2018, progress continued to be made to reduce the number of stateless people through the acquisition or confirmation of nationality. A reported 56,400 stateless people in 24 countries acquired nationality during the year, with significant progress occurring in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, the Russian Federation and Sweden, among other places. In Sweden, for example, an estimated 7,200 people had their nationality confirmed in 2018, as did an estimated 6,400 in the Russian Federation.

Stateless people are not considered nationals under the law of any state. They may not be able to go to school, see a doctor, get a job, open a bank account, buy a house or even get married. They are also generally not counted or registered in the ways the rest of the population is, meaning their needs are not planned for and their existence not acknowledged.

CHAPTER 7

Other Groups or People of Concern

KENYA. A woman from the Turkana host community (right) and her friend, a refugee from South Sudan (left), stand among the crops in the 180-hectare sorghum farm at the Kalobeyei integrated settlement. © UNHCR/Samuel Otieno

Other people of concern is a category of people who, whether as individuals or as a group, need protection or assistance on humanitarian grounds but do not fit into existing population or legal categories.

1.2 million people made up the category ‘other people of concern’

Under certain circumstances, UNHCR provides protection and assistance to individuals or groups “of concern”, who do not fall within the categories of forcibly displaced, returns and/or stateless. Typical examples include returned refugees who are still in need of UNHCR assistance more than a year after arrival, host populations affected by large refugee influxes, and rejected asylum-seekers who are considered to be in need of humanitarian assistance. This category numbered 1.2 million by the end of 2018. In previous years, Venezuelans living in Latin American and Caribbean countries outside of the formal asylum system were previously reported in this category, they are now reported in a separate category: ‘Venezuelans displaced abroad’.

Cash grants, reintegration projects and the Regional Refugee Response Plan

The largest group of individuals in this category were living in Afghanistan, mostly made up of the 489,900 refugees who had returned with UNHCR’s help. This group remained ‘of concern’ while they were in the early stages of their reintegration. UNHCR assists with cash grants and reintegration projects, usually for at least a year after arrival.

Uganda reported assisting some 180,000 people in this category, made up of Ugandan nationals living in refugee-hosting communities. These communities benefitted directly or indirectly from interventions implemented through the Regional Refugee Response Plan. These interventions helped local communities meet the challenges of the arrival of a large number of refugees – including education, health, and water.

Approximately 110,600 people were reported in Guatemala as “others of concern” corresponding to an estimated number of deportees or individuals in transit with possible protection needs. These individuals were mainly from countries in northern Central America, deported from or in transit to the United States of America or Mexico.

As in previous years, Filipino Muslims (80,000) who settled in Malaysia’s Sabah state were reported as “others of concern” by Malaysia. Some 1,900 former refugees and 47,000 former IDPs were reported as “of concern” in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Concern about those at risk of statelessness

Chad reported 36,700 people as “others of concern” at the end of 2018, of which 20,000 were nationals of CAR pending screening and refugee registration and 16,700 were of Chadian descent evacuated from CAR and at risk of statelessness. In Niger there were 27,100 people in this category, comprising mainly Niger nationals displaced from Nigeria who have no access to documentation proving their Nigerien nationality.

Other people of concern is a category of people who, whether as individuals or as a group, need protection or assistance on humanitarian grounds but do not fit into existing population or legal categories.

Special section:

Urban refugees

LEBANON. Syrian refugee Shadi looks over the rooftops of Beirut from his balcony in the Geitawi district. He earns a living tutoring students in Arabic language over Skype through the NaTakallam programme, which pairs displaced persons with learners from around the world. “Being part of NaTakallam is so positive for me. It’s more than just teaching,” Shadi says. © UNHCR/Diego Ibarra Sánchez

The refugee population reflects a global shift towards living in urban rather than rural areas.

In 2018, about 55 per cent of the world’s population was urban, compared with only 30 per cent in 1950. The refugee population mirrors this change. Unlike camp settings, cities and urban areas present certain advantages: refugees can live autonomously and find employment or economic opportunities. However, there are also dangers, risks and challenges. Refugees may be vulnerable to exploitation, arrest or detention, and can be forced to compete with the poorest local workers for the worst jobs.

Understanding the key trends in the urbanization of refugee populations is crucial to ensuring that policies meet the needs and improve the lives of both refugees and host communities. In response to these trends, UNHCR has adopted an urban refugee policy to promote the inclusion of refugees into urban life. Cities of Solidarity is a worldwide initiative that invites cities and local authorities to sign a statement of solidarity in support of refugee inclusion and bringing communities together.

Displaced populations can benefit host communities

UNHCR works to maximize the skills, productivity and experience that displaced populations bring to urban areas, striving to help displaced people find the safety and security they deserve. This, in turn, helps to stimulate economic growth and development within host communities, while enhancing universal access to human rights.

In 2018, the proportion of the refugee population that was urban-based was estimated at 61 per cent globally. The largest urban refugee population was in Turkey, where the vast majority of refugees were reported to be living in urban or peri-urban areas.

Similarly, Germany reported an urban refugee population of more than 1 million given that more than three quarters of the country’s population live in urban areas. Among countries that reported the urban-rural breakdown, Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran both reported urban refugee populations largely from Afghanistan. The largest number of urban refugees in 2018 originated from Syria with 6.3 million people, representing 98 per cent of the entire population for which location was known. This was followed by the Afghan urban refugees, which numbered 2.1 million in urban areas, representing 82 per cent of the entire population, again for which location was reported.

Urban refugee populations comprise more adults and fewer women

The urban refugee population differed in its demographic characteristics from rural populations. More than two thirds of rural refugee populations were under 18 years of age, compared with almost half of urban refugee populations. Among the adult population, there was a higher proportion of men in urban refugee populations (58 per cent) than in rural refugee populations (47 per cent).

CHAPTER 8

Demographic and Location Data

BANGLADESH. Rahima (left), 55, stands outside her shelter for stateless Rohingya refugees in Kutupalong camp, Bangladesh with her children and grandchildren. Rahima first fled Myanmar in 1978 at the age of 14, then again in 1992. Following her most recent flight she says: “I didn’t think I would return here again, I hoped I would live in my homeland.” © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

Who, where and why do we need to know about it?

Knowing who and where people are makes it possible to plan and implement effective and efficient policy responses that address the needs of vulnerable groups and help ensure that “no one is left behind”, as laid out in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.

UNHCR has been making great efforts to improve the quality of data, looking for new ways of gathering information quickly and working with partners. For example, UNHCR is working with IOM and UNICEF to build national statistical capabilities to measure “children on the move”.

Collecting disaggregated data can be challenging in emergency situations, as resources for data collection compete with other acute needs such as the immediate delivery of aid and protection. Even in more stable situations in high-income countries with well-resourced statistical systems UNHCR faces barriers to obtaining disaggregated data..

The availability of disaggregated data varies widely between countries and population groups. In 2018, 131 countries reported at least some sex-disaggregated data. This is a significant decline from previous years, including the 147 countries in 2017. The decline is partially accounted for by more attention being paid to the quality of the estimation of the sex breakdown but also partially due to an increasing reluctance of governments to share data.

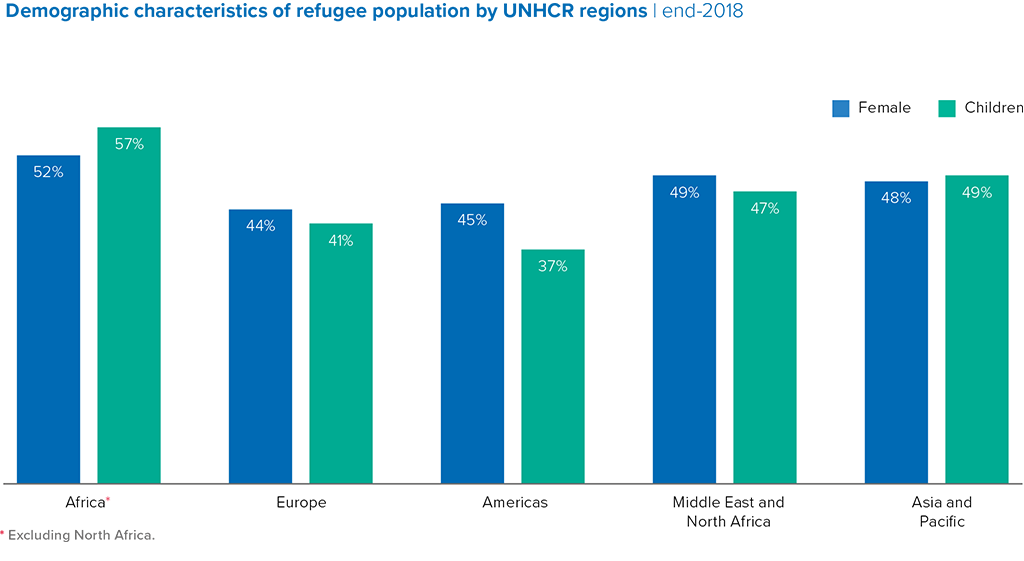

Overall there appeared to be equal numbers of men and women in the population of concern to UNHCR. Of the 31.5 million people for whom age-disaggregated data were available, 52 per cent were children under 18. Differences were also seen at regional level. The lowest proportion of both children and women was seen in the refugee population in Europe where only 44 per cent of the refugee population was female and 41 per cent was under the age of 18. In contrast the highest proportion of both women and children was in sub-Saharan Africa with 52 per cent and 57 per cent respectively.

Where do people live?

Knowing where displaced people are and how they are living is as important as knowing who they are when it comes to delivering assistance and protection. UNHCR classifies locations into urban and rural. Additionally, UNHCR collects data on the type of accommodation individuals live in, especially for refugee populations. This information is important for efficient policymaking and programme design.

Accommodation types are classified as: planned/managed camp, self-settled camp, collective centre, reception/transit camp and individual accommodation (private), as well as various/unknown.

The majority of refugees lived in privately hosted and out-of-camp individual accommodation (60 per cent) at the end of 2018, a proportion that has been stable since 2014. Many countries, especially high and middle-income, reported all refugees living in individual accommodation. In contrast, there were also countries where most refugees were reported as living in some kind of camp setting such as Bangladesh, Tanzania, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Nigeria.

The Syrian refugees were overwhelmingly an out-of-camp population, with more than 98 per cent living in individual accommodation.

Data can be separated to show more than just the number of people in a particular situation, this is known as disaggregated data. Information useful to UNHCR includes how many people in a population are men or women, how many are children or old people and also where people are living.