World Refugee Survey 2008 - Australia

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - Australia, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50c1c.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

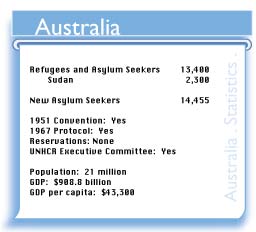

Australia resettled 10,700 refugees during 2007 and granted protection to 1,900 refugees within the country. In August, the immigration minister announced that Australia would reduce its African resettlement from 50 to 30 percent of its total, and increase resettlement quotas for the Middle East and Asia to 35 percent each. The Government explained that the change reflected a commitment to resettling refugees from Myanmar, improved conditions in Africa, and the difficulty some African refugees, particularly Sudanese, had in adapting to life in Australia. A spokesperson for the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) noted that the latter reason seemed to be "at odds with the purpose of a refugee resettlement program."

Refoulement/Physical Protection

Australia deported three Chinese asylum seekers, one democracy activist, and two Falun Gong practitioners, back to China in March. Chinese officials reportedly detained and interrogated the Falun Gong practitioner upon arrival. Other detainees blocked a previous attempt at deporting one of the men by forming a human wall around him, and some detainees went on a month-long hunger strike to protest the deportations and detention conditions. The deportation cost the Australian Government A$45,000 (about $37,700), as it had to purchase five rows of seats to provide an exclusion zone around the deportees on a commercial airline.

Australia returned five Indonesian asylum seekers it intercepted at sea to Papua New Guinea because they had spent more than a week there before attempting to reach Australia.

In January, Australia granted permanent protection to an Iraqi asylum seeker after the national intelligence agency reversed its finding that he was a threat to national security; Australia detained him for nearly five years on the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru.

While Australia's resettlement program extended to some who did not meet the definition of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees in its resettlement program, it did not formally offer complementary protection for those seeking asylum within Australia. Rejected asylum seekers could request relief from deportation on humanitarian grounds at the discretion of the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, but the latter granted it in only about five percent of cases between 1996 and 2003.

In 2001, Australia excised islands along its northern coast from its migration zone and did not permit asylum seekers who arrived at these locations or those intercepted at sea to apply for visas in Australia. Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) officials assessed asylum claims and more senior officials, rather than independent judges, considered appeals. Australia sought other countries to accept those it found to be refugees, although the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship had discretion to grant them visas. Australia returned those it rejected to countries where they had legal residency, or sometimes, where they held forged documents from. DIAC tape-recorded and documented in writing all asylum hearings, and provided asylum seekers with written results in both English and their preferred languages.

In November, the newly elected Labor Government announced the end of Australia's Pacific Solution, a policy under which Australia detained asylum seekers intercepted at sea in a facility on Nauru. By February 2008, the Government had granted Permanent Protection Visas (PPVs) to the final refugees there: Sri Lankan asylum seekers intercepted at sea in February 2007. The Government, however, said it would continue to process asylum seekers intercepted at sea at the detention center on Christmas Island, one of the territories Australia excised from its migration zone.

Refugees who arrived in the migration zone without visas were eligible only for Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs), which permitted them to live, work, and receive health and social services in Australia for three years. TPVs did not, however, allow refugees to return after leaving the country or entitle them to family reunification. Refugees with TPVs could apply for further protection at any point during their stay and for renewal of the TPVs. In November, a court ruled that Australia did not have to give ongoing protection to refugees with TPVs when they reapplied if there was a change in the situation in their home countries that obviated their need for protection. Since 2004, TPV holders could also apply for other migration visas, including employment, business, regional migration, family, or temporary student visas. The newly elected Government announced plans to eliminate TPVs and give permanent protection to all asylum seekers. Refugees with TPVs whom DIAC found no longer in need of protection were eligible for 18-month Return Pending Visas when their TPVs expired to allow them to make arrangements to leave the country. The Minister of Immigration and Citizenship could grant PPVs to anyone who would otherwise be restricted to a TPV.

Australia permitted asylum seekers who arrived with valid visas to apply for PPVs, providing they had not spent more than seven days in a country that could have protected them. Asylum seekers whose claims authorities rejected onshore could appeal to the Refugee Review Tribunal. In June 2005, the Prime Minister established a 90-day limit for interviews and appeals, with DIAC reporting cases that missed the deadlines to the Parliament.

Australia provided assistance with the visa process to asylum seekers through the Immigration Advice and Application Assistance Scheme (IAAAS). IAAAS was available to all detained asylum seekers, as well as those outside detention who did not speak English, had cultural barriers to seeking asylum, were in remote parts of Australia, had disabilities, or had suffered trauma.

Detention/Access to Courts

Australia detained all noncitizens who arrived without visas, including asylum seekers, until their status was resolved. During 2006-07, it detained 290 asylum seekers (out of 3,730) at some point during their asylum process. At the end of 2007, Australia was holding 98 asylum seekers (24 in the first instance and 74 on appeal) with outstanding claims, out of nearly 420 detainees (not including illegal foreign fishermen). Of these, 36 were children whom Australia allowed to live outside detention centers through its community detention program.

In January, Australia released an Iraqi asylum seeker from detention after nearly five years. He had become mentally ill during his detention, and Australia transferred him from Nauru to a Brisbane hospital in 2006. Also in January, an Iranian asylum seeker filed suit against the Government over the emotional and psychological harm he suffered in three years of detention, eventually receiving an award of A$800,000 (about $671,000).

In separate February incidents, Australia intercepted at sea a group of more than 80 Sri Lankans and a group of 7 Rohingyas from Myanmar. Australia detained both groups on Nauru for the rest of the year, until the new Government brought them to the mainland in early 2008.

During the 2006-07 fiscal year (ending June 30), the Immigration Ombudsman issued reports on 367 persons who had been in immigration detention for more than two years, of whom 92 remained in detention. Australia also billed detainees for their detention in lump sums or installments. It could waive fees, but did so only ten times by year's end.

In a report on its visits to detention centers between August and October, Australia's Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) urged the Government to tear down Stage 1 of the Villawood Immigration Detention Center, located in the suburbs of Sydney. Stage 1 was the largest and most secure of Australia's detention facilities and held many long-term detainees with mental illnesses. In addition to the dilapidated and prison-like structure, HREOC criticized the lack of a Mandarin interpreter for the large number of Chinese detainees, and reports that guards made derogatory comments about detainees' religious practices.

Detainees had no way to challenge their detention in court. Australia increasingly released long-term detainees, particularly those in poor health, but this remained a discretionary power of the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship. UNHCR had access to all detention facilities and attempted to visit the main centers every 18 months. Private contractor GSL (Australia) Pty Ltd operated all of Australia's detention facilities.

Australia passed a law in 2005 declaring that the Government should detain children only as a last resort and allowed the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship to permit women and families to live outside facilities under DIAC supervision. As of January, there were 33 children living in alternate detention arrangements. Australian law also required the immigration minister to report any noncitizen in immigration detention for more than two years to the Commonwealth Ombudsman. The Ombudsman had the power to investigate any issues arising from the reports, and could question DIAC officials under oath and enter any detention facility. The Ombudsman could make recommendations, including continued detention, release to community detention facilities, or permanent residency.

In addition to the Ombudsman, HREOC also could monitor detention centers, although it could make only nonbinding recommendations and had to depend on DIAC's goodwill for access to facilities. The Immigration Detention Advisory Group (IDAG), established in 2001 to monitor services and make recommendations to the minister, had unfettered access to detention facilities, but its role was advisory only.

Australia provided identity documents to all refugees and asylum seekers outside detention facilities.

In 2004, courts found that indefinite detention of foreigners was constitutional if the Government intended to deport them, that international human rights obligations did not restrict executive power to detain, that their detention need not be reasonable or proportionate to avoid being punitive, and that no court may order the release of foreign children from detention.

Refugees and asylum seekers in Australia proper, but not those detained in offshore facilities, had full access to the courts (although not to challenge detention).

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Outside of detention, all refugees and asylum seekers enjoyed complete freedom of movement within Australia. The Government issued international travel documents to those with permanent protection; they were free to travel abroad and return as long as they did not travel to their country of origin.

The Government did not keep records of how many travel documents it issued to refugees. Refugees with TPVs did not have the right to return to Australia if they left. Asylum seekers who left the country without showing good cause automatically forfeited their claims.

In December 2006, the city council of Tamworth in New South Wales refused to accept five families of resettled Sudanese refugees. The Mayor said the council feared the refugees would not find work, might carry diseases, and would sexually harass local women. In January, the town relented and agreed to accept them.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

The Government permitted refugees to work.

Asylum seekers who arrived with valid visas and who spent fewer than 45 days of the previous year in Australia before applying for asylum could work while the Government processed their claim if their original visa allowed them to work. Those whose visas did not allow them to work had to apply for permission to work and demonstrate a need to work. The Government also suspended work rights when it rejected claims, even if the asylum seeker filed a request to the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship to stay on humanitarian grounds.

Refugees had full rights to practice professions, own permanent and movable property, open bank accounts, and run businesses. They had full protection under Australia's labor laws.

Public Relief and Education

The Government provided newly arrived refugees and humanitarian entrants in their first six months with orientation, information, and referrals; assistance in finding housing; clothing and household goods; short-term torture and trauma counseling; and emergency medical assistance. Refugees and humanitarian entrants were exempt from the two-year waiting period to receive unemployment and sickness benefits, student allowances, and other payments. Those with dependent children could receive family tax benefits and child care benefits. For their first five years, the Government provided refugees with settlement services.

PPV and TPV holders were eligible only for short-term torture and trauma counseling. Asylum seekers with pending applications and visas with work rights received government health insurance. Those without work rights did not get government health insurance, but the Australian Red Cross aided some.

Immigration detention centers offered 24-hour medical, dental, and psychological health services. They also offered educational programs, including English classes. Both refugees and asylum seekers had the same access to primary and secondary education as nationals. Refugees with TPVs and asylum seekers had limited access to post-secondary education.

USCRI Reports

- East Asia: Australia's Policies Put Refugees at Risk, Leave Others in Limbo (Press Releases)