U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants World Refugee Survey 2007 - United States

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 11 July 2007 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants World Refugee Survey 2007 - United States, 11 July 2007, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4696388fc.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Refoulement/Physical Protection

The U.S. Coast Guard returned nearly 800 Haitians and 2,300 Cubans it intercepted at sea as they tried to reach Florida. The United States maintained a policy of interdicting Cubans and Haitians on the high seas and returning them to their countries of nationality unless it determined any were refugees. Authorities advised Cubans, but not Haitians, of their right to seek asylum. The only way for Haitians to claim asylum was to shout out their fear of return to Haiti, and even this did not always work. The Coast Guard transferred those it found to have a credible fear of return to the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where Department of Homeland Security Officers interviewed them. In all, the Coast Guard interdicted nearly 6,100 foreign nationals at sea.

In April 2007, the United States announced plans to accept 200 asylum seekers per year from Australia's offshore detention centers and to send 200 Cubans and Haitians from Guantanamo to Australia yearly.

The United States was not party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees but was to its 1967 Protocol. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) prohibited refoulement and established procedures for admitting refugees and granting asylum. The amendments to the INA in the 2001 Patriot Act and the 2005 Real ID Act prevented the admission of many refugees, barred those who gave "material support" in any form, including money, shelter, food, water, or clothing to any organization the law deemed terrorist, even under duress, from resettlement or asylum. According to the amendments, any "group of two or more individuals, whether organized or not, which engages in, or has a subgroup that engages in" terrorist activity qualified as a terrorist organization. The law did not limit its definition of "terrorist activity" to targeting civilians for political violence but included any unlawful act using any "weapon or dangerous device (other than for mere personal monetary gain) ... to cause substantial damage to property."

This definition barred even supporters of pro-democracy rebel groups, such as the Karen National Union of Myanmar and the Hmong of Laos and Montagnards of Vietnam who fought alongside U.S. forces in the 1960s and 1970s. In January 2007, the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Homeland Security exercised their discretion to exempt persons who were not public safety or national security risks to the United States by issuing waivers for supporters of several Myanmarese groups, the Cuban Alzados, and the Tibetan Mustangs. Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff also pledged to seek further discretionary exemption authority from Congress. The Department of Homeland Security also announced a duress exception for those compelled to aid groups that met the broadest definition of terrorist, but not for similar victims of designated groups such as Hezbollah or the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia.

The material support provision also blocked more than 4,000 refugee and asylee applications for permanent residence, at least 550 refugee and asylee petitions for reunification with spouses and minor children, and 600 asylum applications. The Government processed four asylum seekers and five refugees under the duress exception, and thousands of refugees, mostly from Myanmar, received the benefit of the waivers authorized by the Secretary of State and Secretary of Homeland Security.

Under the INA, applicants were ineligible for asylum and refugees were deportable if they committed "aggravated felonies," including any act of theft or violence punishable by a year or more in prison, whether or not a court actually sentenced them to such punishment. They could apply for withholding of removal if persecution upon return was more likely than not, but were ineligible for this if a court had sentenced them to five years imprisonment or more; in such cases, their only avenue for relief was an application under the Convention Against Torture.

Asylum seekers making claims to avoid deportation made their cases in front of immigration judges. They had the right to appeal to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) and subsequently to federal courts, and to the assistance of counsel at their own expense.

A study of the decisions by immigration judges from 1994 to 2005, conducted by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University and released in 2006, found that the median rejection rate was 65 percent, but that eight judges denied asylum to 90 percent of applicants, and two granted asylum to 90 percent. The study also reported that judges denied the claims of 93 percent of asylum seekers without attorneys, and 64 percent of the claims of those who had attorneys.

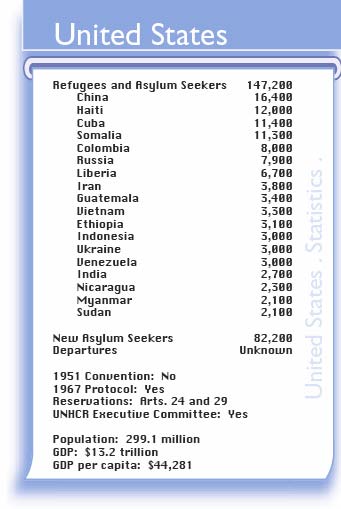

The United States accepted more than 41,000 refugees for resettlement, and granted asylum to more than 23,000. More than 83,000 asylum seekers had claims pending at the end of the year.

Detention/Access to Courts

The United States held between 2,000 and 3,000 asylum seekers in detention on any given day during the year. Immigration officials detained them at ports of entry for not having valid documents, and detained some with proper documents if they intended to seek protection immediately. Some asylum seekers voluntarily chose to return to countries where they might be in danger in order to avoid detention.

Detainees sometimes suffered from a lack of responsive medical services. Two facilities failed to issue handbooks informing detainees of their rights, and materials were not available in Spanish and other common languages. Even family centers held families with young children as long as two years, separated children as young as six from their mothers at night, restricted meal times, and limited access to the outdoors.

In a small number of cases, authorities used alternatives to detention such as electronic tracking devices that allowed asylum seekers to live in communities under supervision.

Refugees, asylees, and asylum seekers received documents attesting to their legal status in the country.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Refugees and non-detained asylum seekers could travel freely within the United States. They had to notify the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) of any changes of address but USCIS' poor recordkeeping caused asylum seekers to miss notification of court appearances and case decisions. The Government required rejected asylum seekers to report regularly to immigration officials if they could not yet deport them.

Refugees and asylees could apply for international travel documents. However, backlogs in processing made it difficult for refugees and asylum seekers to travel for work or to sudden events like funerals.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

Refugees and asylees could work legally, but the Government ceased issuing refugees admitted for resettlement work permits upon arrival. Instead, they received them by mail, and sometimes had to wait more than the official limit of 30 days to receive them.

Asylees obtained work permits automatically when the Government granted their cases, but asylum seekers had to wait 180 days after filing an application before they were eligible.

USCIS changed the policy on work permits for asylees, extending their validity from one to two years. Refugees and asylees could open bank accounts and own property.

Public Relief and Education

Refugees had access to education on par with nationals. Undocumented asylum seekers had virtually no access to public assistance, however, apart from public education and emergency medical services.

The United States aided refugees for eight months after arrival or grant of asylum, and they were eligible for public assistance for up to five years. The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act limited the eligibility for Social Security Income to seven years for non-naturalized refugees, asylees, and Cuban or Haitian entrants if they entered after 1996. Around 6,600 refugees lost benefits in 2006, bringing the total to nearly 12,000.

Language barriers prevented many elderly refugees from passing naturalization exams, and the 1951 Convention did not require naturalization for public relief in any event. The law precluded relief agencies from providing services to undocumented immigrants.