U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants World Refugee Survey 2007 - Algeria

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 11 July 2007 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants World Refugee Survey 2007 - Algeria, 11 July 2007, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/469638785.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Refoulement/Physical Protection

There were no reports that Algeria forcibly returned refugees to their countries of origin but it deported an indeterminate number of refugees and asylum seekers registered with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to its border with Mali. Authorities ordered others they arrested to leave the country within 15 days but took no further action. Monitoring of interception measures in border areas was not possible. Algeria also deported thousands of other migrants, some of them likely asylum seekers, to Sub-Saharan Africa without a chance to apply for asylum or challenge their deportation. UNHCR's operational capacity in terms of legal assistance was limited to the capital.

The Government threatened to deport some 66 refugees, mostly from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo-Kinshasa), whom it had apprehended among some 700 migrants near the Moroccan border at the end of 2005, and sought laissez-passers from the Congolese Government. Third countries resettled six of them.

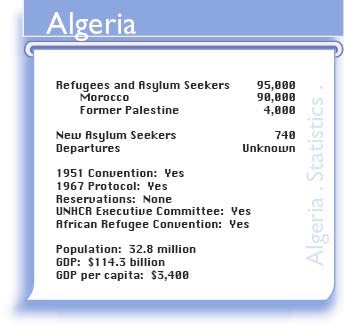

Algeria was party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Convention), its 1967 Protocol, and the 1969 Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, without reservation. The 1989 Constitution provided that in no case may a "political refugee" with the legal right of asylum be "delivered or extradited." A 1963 decree established the Bureau for the Protection of Refugees and Exiles (BAPRA) in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and called for an appellate board consisting of representatives of various ministries and the UNHCR but, because the authorities never requested UNHCR to designate its representative, the agency did not participate. The law required applicants to submit appeals within one month after denial or within one week in cases of illegal entry, order of expulsion, or applicants the authorities deemed a security risk. The decree authorized BAPRA to decide cases and stipulated its recognition of those UNHCR had already recognized. The Government, however, granted asylum to only one refugee during the year, an Iraqi, and he received a three-year residence permit.

The Government recognized the Sahrawi and all 4,000 Palestinians as refugees but, as in the past, delegated virtually all other cases to UNHCR during the year. Algerian authorities told a delegation of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) that responsibility for human rights and related matters lay with the government-in-exile of the Polisario rebel group from Western Sahara, a claim the delegation rejected. More than 700 persons applied in 2006, nearly half in the last quarter, including more than 300 from Côte d'Ivoire, nearly 200 from Congo-Kinshasa, and more than a hundred from Cameroon. The number of refugees (other than Sahrawi and Palestinians) and asylum seekers with cases pending at the end of the year was nearly 1,000, mostly from Congo-Kinshasa, Côte d'Ivoire, and Cameroon in urban areas and another 200 from Mali and Niger in the countryside. According to UNHCR, "Due to various factors, such as the restoration of peace and security in the country, the brisk pace of economic growth and the restrictive asylum policies in the EU zone, Algeria is in the process of becoming an asylum country for a growing number of sub-Saharan Africans.... Durable solutions will have to be identified to a large extent locally." The official Algerian attitude, however, was that there were no bona fide sub-Saharan refugees in the country as they either should have sought protection in a neighboring state or presented themselves to the border authorities. Authorities considered all undocumented sub-Saharan Africans to be illegal aliens.

In February, torrential rains caused flooding that injured a number of Sahrawi refugees in the remote Tindouf camps and swept away the dwellings of about 12,000 refugee families. According to UNHCR, juvenile delinquency was also becoming a problem due to a lack of activities for young people.

Detention/Access to Courts

Algeria continued to detain 66 refugees (58 from Congo-Kinshasa, 7 from Côte d'Ivoire, and 1 from Eritrea) whom it had apprehended among some 700 migrants at the end of 2005 in the Maghnia region near the Moroccan border. It charged them with illegal entry and illegal journey in Algeria and moved them to a facility in Adrar. The Government denied UNHCR access to the facility until March 2006, whereupon a protection team from UNHCR's Geneva headquarters conducted status determinations and granted them refugee status. The Government did not inform UNHCR when it detained refugees or asylum seekers. The Maghnia detainees managed to contact UNHCR themselves. They remained in detention as of April 2007.

Police arrested some 30 refugees and asylum seekers per month, generally sub-Saharan Africans, and presented them to the courts. With the help of lawyers and UNHCR's intervention, refugees and asylum seekers in Algiers challenged their own detention and generally won release. Those who authorities arrested outside the capital, however, did not have access to counsel or defense. Refugees and asylum seekers did not have access to courts to vindicate their rights as they had to avoid them for fear of arrest.

The 1963 decree empowered BAPRA to issue personal documentation to refugees. UNHCR issued some 500 "To whom it may concern" letters to asylum seekers, but was only able to do so in Algiers. The security forces respected UNHCR attestations certifying that a person is a refugee or a person of concern more than they did the letters. Security constraints left the rest of the country uncovered.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

The Government allowed the Western Sahara rebel group, Polisario, to confine nearly a hundred thousand refugees from the disputed Western Sahara to four camps in desolate areas outside the Tindouf military zone near the Moroccan border. According to Amnesty International, "This group of refugees does not enjoy the right to freedom of movement in Algeria.... Those refugees who manage to leave the refugee camps without being authorized to do so are often arrested by the Algerian military and returned to the Polisario authorities, with whom they cooperate closely on matters of security." Polisario checkpoints surrounded the camps, the Algerian military guarded entry into Tindouf, and the police operated checkpoints throughout the country. In May, a UNHCHR delegation attempted to examine human rights conditions in the Polisario-administered camps but was unable to collect sufficient information and said closer monitoring was "indispensable."

The Polisario did allow some refugees to leave for education in Algeria and elsewhere and to tend livestock in the areas of the Western Sahara it controlled and Mauritania. It did not, however, allow members to leave with their entire families. An unknown number reportedly held Mauritanian passports and the Algerian government also issued passports to those the Polisario permitted to travel abroad.

The Government issued no international travel documents.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

Algerian law severely restricted the rights of foreigners to work and made negligible exception for non-Palestinian refugees. The one refugee to whom the Government granted asylum during the year was in the process of obtaining a work permit as of March 2007.

The 1981 Employment of Foreign Workers Law and the 1983 Order of the Ministry of Labor allowed only single-employer work permits for jobs for which no national, even one abroad, was qualified. Employers had to file justifications consistent with the opinions of workers' representatives. Permits were valid for no more than two years and renewal required repetition of the same procedure. Employees could not change employers until they completed their contract and then only in exceptional circumstances after consultation with the previous employer. Violators were subject to a fine and/or imprisonment from ten days to a month. The only unskilled foreigners the law permitted to work were those with "political refugee" status.

The 1990 Labor Law, amended in 1997, incorporated the same national labor protection requirements, without exception for refugees. A 2005 decree established regional labor inspection offices to enforce laws regulating the employment of foreigners and to take action "against all forms of illegal work." According to UNHCR, Palestinian refugees had access to the labor market under a special dispensation.

Although the Constitution provided that "Any foreigner being legally on the national territory enjoys the protection of his person and his properties by the law," refugees could own moveable property only. The desert surrounding Tindouf where the guerrillas confined refugees from Western Sahara supported virtually no livelihood activity except that refugees could own goats and sheep.

Public Relief and Education

In February 2007, UNHCR and the World Food Programme (WFP) found dire conditions in the camps including anemia among pregnant and lactating women. The refugees were entirely dependant on humanitarian aid and agencies had to cut food supplies toward the end of 2006 and had only partially restored them later. In response to the February floods, the Government sent eight army planes with 4,000 tents, 14,000 blankets, and 62 tons of food and more aid in four convoys from neighboring provinces. The European Commission donated $1 million in flood relief. Regular aid budgets included $21 million for the WFP, $3 million for UNHCR, $2 million for operational partners, and $860,000 for implementing partners. Algeria itself donated $60,000 to UNHCR.

Most of the refugees in the camps around Tindouf lived in brick or mud shacks, had precarious access to health services, and could not adequately educate their children. According to WFP, about 35 percent of children under five in the Tindouf camps suffered from chronic malnutrition. An observer in late 2003 described a "system of clientelism, permitting leaders to keep a strong grip on the population.... Everyone has to beg for the leaders' favors. These favors can consist, for example, of a medical operation abroad, studies, a job with the Polisario, the right to leave the camps, and probably economic favors as well."

The Polisario and Algerian authorities tightly controlled the activities of international aid workers and the Polisario reportedly diverted substantial amounts of aid from refugees for its own purposes. Some aid agencies distributing European Commission aid, supportive of the Polisario's political and military enterprise, did not distinguish between the organization and the refugees. The Government claimed there were about 150,000 refugees in the camp but refused to allow a registration census.

Enrollment in public schools required residence permits, which de facto and UNHCR-recognized refugees did not have. Some 21 refugee children enrolled in private schools with UNHCR paying the fees. Refugees and asylum seekers, however, did have access to free public health facilities and UNHCR paid a pharmacy to provide their medicines.

Neither the national Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Algeria prepared for international donors, the Common Country Assessment, nor the UN's joint plan of action with the Government for 2007-2011, included refugees.