Nations in Transit 2012 - Bulgaria

| Publisher | Freedom House |

| Publication Date | 6 June 2012 |

| Cite as | Freedom House, Nations in Transit 2012 - Bulgaria, 6 June 2012, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4fd5dd31c.html [accessed 7 June 2023] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Capital: Sofia

Population: 7.5 million

GNI/capita, PPP: US$13,440

Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Bank Indicators 2010.

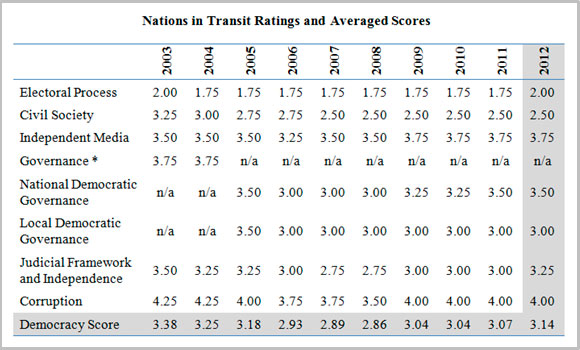

* Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance, to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects.

2012 Scores

| Democracy Score: | 3.14 |

|---|---|

| Regime Classification: | Semi-Consolidated Democracy |

| National Democratic Governance: | 3.50 |

| Electoral Process: | 2.00 |

| Civil Society: | 2.50 |

| Independent Media: | 3.75 |

| Local Democratic Governance: | 3.00 |

| Judicial Framework and Independence: | 3.25 |

| Corruption: | 4.00 |

NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year.

Executive Summary:

Since the collapse of communism in 1989, Bulgaria has consolidated its system of democratic governance with a stable parliament, sound government structures, an active civil society, and a free media. Power has changed hands peacefully, with the country enjoying more than a decade of stable, full-term governments. Bulgaria officially joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2004 and the European Union (EU) in 2007. These successes notwithstanding, events in 2011 highlighted the persistence of challenges facing Bulgaria's democratic institutions. Presidential and local elections were marked by severe administrative inefficiency and delayed tabulation of results. Inefficiency and corruption within the judiciary are still considered a major stumbling block in Bulgaria's battle against high-level corruption and organized crime. A series of small bombings targeted opposition-oriented media and political parties during 2011, and the killing of an ethnic Bulgarian youth in September triggered a series of street protests against local organized crime and the Roma minority.

National Democratic Governance. President Georgy Parvanov's attempt to form his own political party failed to gain momentum, indicating the strength of a constitutional tradition that prohibits presidential parties. Public trust in the government and in Prime Minister Boyko Borisov continued to decrease slightly during the year, but did not vary greatly from the level of trust in the previous three governments and prime ministers. Political tensions between the outgoing president and the prime minister appeared to stabilize, especially after the GERB party candidate won the presidency in October. However, the government's practice of ad hoc policymaking persists in the absence of more programmatic governance strategies. Bulgaria's national democratic governance rating remains unchanged at 3.50.

Electoral Process. Concurrent presidential and municipal elections proceeded peacefully in late October. In addition to the usual allegations of vote buying and manipulation of results, the elections were characterized by considerable administrative inefficiency, resulting in problems with electoral registers, long voting queues, and delays in the announcement of official results. Most election coverage in 2011 appeared in the form of paid political content, creating a dearth of independent information. Due to the striking administrative mismanagement of the electoral process, Bulgaria's electoral process rating drops from 1.75 to 2.00.

Civil Society. The civic sector in Bulgaria is well regulated, generally free to develop its activities, and well established as a partner both to the state and to the media. However, the ability of nongovernmental organizations to raise funds domestically remains limited, impeding the emergence of rich feedback links between NGOs and local communities. The absence of specific regulations for lobbying activities also creates a space for dubious practices and hinders the ability of civil actors to effectively express and pursue the interests of various segments of society. Therefore, Bulgaria's civil society rating remains unchanged at 2.50.

Independent Media. Media freedom is legally protected in Bulgaria, and citizens have access to a diverse array of media sources. Print media are generally free from specific regulations. The year 2011 witnessed further concentration of media ownership and increased accusations of overlap between media and political interests. Bulgaria's two top-selling dailies Trud and 24 Chasa were acquired by businessmen Ognyan Donev and Lyubomir Pavlov and the BG Printmedia group in a deal initiated in December 2010 but not confirmed until April 2011. In February a small bomb went off at the entrance of Galeria, a newspaper known for its critical coverage of the GERB government. During the October election campaign, the car of television anchor Sasho Dikov, also known for his anti-GERB views, was blown up in front of his apartment. Bulgaria's independent media rating remains unchanged at 3.75.

Local Democratic Governance. There were no notable changes in the institutional setup or effectiveness of local governance in 2011. The processing of the local election results in October came under severe criticism, serving as the basis for numerous court appeals, which are still pending. 2011 is the opening year for the planning of the EU 2014-20 financial period, in which Bulgarian municipalities will have improved opportunities to access significant resources. However, this improved prospect is counterbalanced by continuing sluggish recovery from the global economic downturn. Bulgaria's local governance rating remains unchanged at 3.00.

Judicial Framework and Independence. Increased efforts to combat corruption and organized crime have often foundered in Bulgaria's judiciary, with cases subject to lengthy procedural delays, defective pre-trial investigations, and dismissal on technicalities. The establishment of specialized courts for high-level corruption cases was postponed until 2012 after the 2010 law establishing them was brought before the constitutional court in February. In July, lawmakers rejected legislation that would have enabled asset seizures in cases of suspected corruption. Judicial appointments by the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC), the self-governing body of the judicial system, triggered wide professional and civil society calls for resignation and reform. An investigation led by the European Association of Judges determined that Interior Minister Tsvetan Tsvetanov's persistent threats endangered the independence of the justice system and violated European standards for the rule of law. Owing to increasing threats to the judiciary's independence, the rating for judicial framework and independence lowers from 3.00 to 3.25.

Corruption. Gradual progress in the field of corruption continued in 2011, while the negative effects of increased government fiscal pressures in the light of the global economic downturn have eased. At the same time, public perceptions and concerns about corruption remain relatively high. The system of bodies charged with fighting corruption continues to lack sufficient coordination and clarity of responsibility and accountability. The inability of authorities to curb rampant organized crime, particularly at customs check-points, caused the European Union to back out of scheduled talks to admit Bulgaria to the Schengen customs-free zone. Owing to a lack of forward momentum in Bulgaria's anticorruption agenda, the corruption rating stays at 4.00.

Outlook for 2012. The crucial goal for Bulgaria's government in 2012 will be controlling the domestic consequences of the global financial and economic crisis while implementing long-overdue reforms in sectors such as healthcare, higher education and the judiciary. The government still enjoys comfortable levels of public support and has a window of opportunity to pursue long-term goals. Its biggest challenges remain the effectiveness of public spending and the measures to address the problems of organized crime and corruption.

National Democratic Governance:

The constitution adopted in 1991 established Bulgaria as a parliamentary democracy with a strong system of checks and balances between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Citizens may participate in the political process through elections, consultations with the legislature, and participation in civil society organizations or the media. Bulgaria's unicameral parliament, or National Assembly, has formative powers over the other two branches, but after their formation they are independent. One peculiarity of the Bulgarian system is the role of the presidency, which carries relatively few governance powers, but a high level of legitimacy due to direct elections.

Bulgaria's political system has enjoyed considerable stability over the last decade; the present government is the fourth in a row which seems set to serve its full, 4-year constitutional term. Although a significant majority of Bulgarian citizens report dissatisfaction with the performance of Bulgarian democratic institutions and leaders, no alternative non-democratic alternatives seem viable.

At present, the two dominant forces in Bulgarian politics are the center-left Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), once led by President Georgy Parvanov, and the center-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) led by Prime Minister Boyko Borisov. Since the parliamentary elections of 2009, GERB has controlled 117 out of the 240 seats in the National Assembly. Borisov and GERB have maintained the support of a parliamentary majority by courting diverse parties such as the nationalist-populist Ataka and the center-right Blue Coalition, as well as various independent deputies, most of whom come from the parliamentary group of Order, Law and Justice (RZS), which disintegrated during the course of 2011. Even though it is a minority government, GERB has demonstrated its ability to sustain support within parliament. Overall levels of public approval for the government and its leader are not high, but they are comparable to the approval levels of all three previous governments and prime ministers in the middle of their respective terms.

In mid-July two small bomb blasts took place in the vicinity of the RZS headquarters, as well as close to an office of DSB, a party from the Blue Coalition. Police reported that the blasts appeared to have been designed for maximum public visibility, rather than to inflict damage or casualties. Interpretations varied between claims that the GERB government was trying to intimidate smaller parties just before a vote of confidence in Parliament, and claims that the blasts were actually attempts on the part of the political opposition to influence the last-minute editing of the annual organized crime monitoring report by the European Commission, whose final text was up for approval later the same week. At year's end, the police investigation had yielded no results, and no new facts lending support to either the interpretations had emerged.

The relationship between President Parvanov and the other members of the executive branch, particularly Prime Minister Borisov, was turbulent in 2009 and 2010, with the president aggressively and outspokenly opposing many policies of the ruling government. The crisis peaked in November 2010, when Parvanov, formed a civic-movement-cum-presidential-party called the Alternative for Bulgarian Revival (ABV), in violation of a longstanding constitutional convention that prevents the presidency from endorsing any one party above others. ABV continued to exist in 2011, but it never gained momentum and failed to put forth any official candidates in the 2011 local elections. Relations between the government and the outgoing President Parvanov appeared to improve, or at least avoid direct confrontation, especially after GERB party candidate Rosen Plevneliev was elected president in October. Nevertheless, the usual governance issues remained as Prime Minister Borisov's practice of ad hoc policymaking persisted in place of more programmatic governance strategies.

Electoral Process:

Bulgaria's president is directly elected, and seats in parliament are apportioned based on a system of proportional representation, with a four percent threshold. All Bulgarian elections since 1991 have been deemed free and fair by international observers, though allegations of vote-buying and other manipulations have been common in recent years. A new electoral code adopted in 2010 combined Bulgaria's existing electoral laws into a single document and introduced a number of controlling mechanisms aimed at reducing election day fraud. The 2010 code also introduced a preferential voting component to local and parliamentary votes, allowing candidates to move to the top of their party's list on the ballot if "preferred" by at least 10 percent of voters. Residency requirements, another innovation of the new code, have been criticized for limiting the voting power of Bulgarian citizens living abroad, especially Bulgarians residing in Turkey.

The first presidential and municipal elections conducted under the new electoral code took place in October 2011, resulting in an overwhelming victory for GERB. A GERB candidate, Rosen Plevneliev, won the presidency. GERB also came out as the most popular political party in the elections for local councilors, and made significant inroads in the local government structures by electing mayors in most big cities. The BSP came in second in both the presidential race, and in the elections for mayors and local councilors. Yet, the party lost its hold over some larger cities in the country, such as Varna. Overall, the election consolidated a majority rule for GERB and a group of independent MPs in parliament, extending considerable power to the ruling party.

In the presidential race, the three main candidates were Rosen Plevneliev, Ivaylo Kalfin (BSP), and Meglena Kuneva (independent). In the first round, Plevneliev received 40.11 percent of the vote, while Kalfin received 28.96 percent and Kuneva 14 percent. Plevneliev won the second round against Kalfin by a relatively small margin: 52.58 percent to 47.42 percent. Voter turnout was relatively high at about 51 percent during the first round and 54 percent during the second.[1]

Regulations introduced by the 2010 code to limit fraud had the negative side-effect of slowing down both voting and vote tabulation, leading to delays in publishing the results. The results for some districts were delayed by more than 24 hours after the legal deadline and several reports of unauthorized people entering the premises where the counting was taking place. Another serious problem was the omission of citizens, who were entitled to vote, from the electoral registers. The scale of this phenomenon is yet to be established, but the situation highlighted the need for more efficient management of electoral registers. Some of the local elections produced very close results and allegations of manipulations raised arguments for rerunning the elections in some of the municipalities. Mayoral elections for the city of Pleven saw flagrant instances of ballot stuffing in some of the polling stations, but the official results – which put GERB's candidate ahead by fewer than 400 votes – were upheld in court on December 29.[2] The BSP has challenged the results of the presidential race before the Constitutional Court, which also ruled to uphold the official numbers.[3]

Election campaigns and media coverage of the elections were generally competitive and fair. However, certain problems remain concerning full and unbiased coverage of the elections. One is that all electoral communications are paid by the candidates and parties. This gives an advantage to larger parties, which are eligible to receive campaign financing from the state, while independent candidates rely on private donations to fund their campaigns. In terms of formatting, media advertisements are often indistinguishable from genuine journalistic content and election coverage. State-funded media are strictly proscribed from taking sides in their coverage of the campaign – a rule introduced to ensure fairness, but which has actually scared many reporters away from in-depth election coverage. Those journalists who do cover the elections often keep to safe, non-partisan issues, resulting in disproportionate emphasis on problems like vote-buying.

An outbreak of anti-Roma violence in September 2011 heavily influenced the campaign rhetoric of some parties. A simmering conflict involving associates of Tsar Kiro, an influential Roma businessman of dubious reputation, erupted into a night of protests and arson when a driver allegedly working on Kiro's instructions ran over and killed a 19-year-old boy. The protests against "Roma criminality" spread across the country in the ensuing days, resulting in at least one racially motivated beating of two Roma boys in the town of Blagoevgrad. Some political parties, especially Ataka and VMRO, exploited these incidents to bolster nationalist support in the October presidential and local elections. Volen Siderov, the leader of Ataka, appeared on television expounding on the dangers of Roma criminality and defending the protesting crowds as conscientious citizens. However, this approach failed to unify the nationalist vote, which was scattered among numerous small parties. Ultimately, Ataka badly lost the elections, demonstrating a positive trend that nationalistic sentiment cannot be used for swinging political campaigns.

Civil Society:

The Bulgarian constitution guarantees the right of citizens to organize freely in associations, movements, societies, and other civil society organizations. During the period of postcommunist transition many civil society organizations emerged and became very active at the local and national levels, achieving considerable influence. Registration and tax regimes are relatively simple and stable. Public benefit nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are not obliged to pay direct taxes and are allowed to carry out for-profit activities that do not interfere with their stated aims if these projects are registered and taxed separately.

Under the Non-economic Purpose Legal Entities Act, the Bulgarian Ministry of Justice maintains a central register for entities that define themselves as acting in the public interest. By the end of 2011 there were 9,137 entries in the register, an increase of almost 10 percent since 2010.[4] Of these, 86 percent are associations, close to 14 percent are foundations, and 0.5 percent are branches of foreign-based NGOs. A nongovernmental web portal for NGOs, launched in 2010, contained 5,302 entries in 2011, compared to 5,094 entries in 2010.[5] Among these web-registered NGOs, 267 defined their basic activity as related to environmental issues, 191 as related to human rights, 137 as related to ethnic issues, and 77 as related to women and gender issues. The two registers indicate that Bulgarian NGOs cover various social spheres (health, education, social services), rights issues (human, minority, gender, religious), public policy and advocacy (with an increasing interest for environmental issues), business and development, and sports. Most of the organizations, especially in the nongovernmental online register, appear to be active.

In 2011, some members of the GERB government appeared more receptive to civil society input than others. Minister of Justice Margarita Popova (who was elected vice president in October) engaged cooperated all year with the Civic Council, a consultative body consisting of representatives of NGOs and judicial professional organizations. In mid-2011, Minister Popova made a clear statement that the governance of the judiciary is in a deep crisis and declared a strong commitment to reform, including constitutional amendments.[6] The Civic Council has been invited to play an important role in the shaping of the much needed reform agenda.

A less promising example of government-civil society relations was set by Minister of Interior Tsvetan Tsvetanov, whose aggressive rhetoric against the Association of Bulgarian Judges drew shocked responses from the European Association of Judges and other organizations. In June 2011, during a conference on Roma integration Tsvetanov also embarrassed Roma representatives by declaring that EU funds for Roma integration have been abused by Roma NGOs.

Such instances of poor diplomacy notwithstanding, Bulgaria's EU membership has generally strengthened the voice of civil society in government, as involvement of numerous stakeholders is often a condition of EU funding, specifically with regard to EU Structural and Cohesion funds. EU membership also facilitates cooperation and coordination between organizations with a similar scope of activities; if they want to get their voice heard, they have to be able to choose representatives in the respective committees and governmental bodies. This trend is very well illustrated by developments within the environmental NGO community. In 2011, for the first time in 9 years, environmental NGOs were successful in coming together for a national conference that elaborated joint input for the strategic documents covering the next programming period up to 2020. In 2011 trade unions and the employers' organizations continued an active dialogue with the government on financial and economic issues. Small and medium enterprises remained outside the scope of the activities of the trade unions.

Despite financial hardships brought on by the 2008 crisis, NGOs have found inexpensive ways to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of their activities by making greater use of technology. Environmental NGOs, in particular, have been very successful in using the new social networks and internet platforms to advocate for their causes.[7]

With the increase in the number of different NGOs – especially those whose main task is to influence public decisions through advocacy – the absence of specific regulations for lobbying activities creates a space for dubious practices and hinders the ability of civil actors to effectively express and pursue the interests of various segments of society. The debate on whether Bulgaria needs a special law on lobbying activities has been very active for several years. In 2009 the adoption of such a law was in the program of the GERB party, but was dropped in late 2010 in favor of a register of lobbyists and lobbying organizations, similar to the Joint Transparency Register shared by the European Commission and the European Parliament. No progress was made in 2011 towards creating the legal basis for such a register.

The educational system itself is free of political influence or propaganda. However, during 2011 (and particularly on the eve of the local elections), a few school activities, including sporting events, were used as opportunities for GERB propaganda.

Independent Media:

Media freedom is legally protected in Bulgaria, with citizens enjoying unrestricted access to a rich variety of media sources. The right to information is also enshrined in the constitution and in the Law on Access to Public Information. However, this legal framework lacks specialized legislation addressing the protection of journalists from victimization. Whatever protection exists is due to general laws protecting citizens and to the respect afforded to journalism as a profession, as well as the popularity of individual journalists and media sources. Libel is a criminal offense in Bulgaria, but the penalty is a fine that rarely exceeds US$10,000. Despite numerous libel cases, the courts tend to interpret the law in favor of freedom of expression and convictions are relatively few.

Print media are free from government control and regulation. Electronic media are regulated through the Law on Radio and Television by the Council for Electronic Media (CEM), which has the dual role of governing state-owned national radio and television and regulating the rest through licensing and registration. Although the CEM is not under government orders, parliament must approve its budget. Throughout its existence, the council has had a reputation of political dependence and has been heavily criticized for the manner and quality of its regulatory actions. The country's switch to digital broadcasting – particularly the parliament's oversight of the CEM in this process – has also left ample room for the influence of political and special-interest agendas with respect to electronic media. In practice, each new government introduces changes in the electronic media law and/or in CEM, in order to have tighter control over the public electronic media in the country.

The Bulgarian press market is characterized by a high number of dailies per capita and low newspaper circulation. With the exception of a few local newspapers and the official State Gazette, all print media in Bulgaria are privately owned, with some under foreign ownership. The two highest circulation dailies, Trud and 24 Chasa, were owned by the German group Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (WAZ) until they were sold to three Bulgarian entrepreneurs in late 2010. After the sale a serious conflict, which is still pending in court, emerged between the new owners. This conflict has not had a visible impact on the content and the policy of the papers, which still remain considerably influential.

In 2009-10 a new player entered the print media market, the New Bulgarian Media Group (NBMG), whose hold on the media market continued to grow in 2011. It currently owns a daily (Telegraph) with reportedly the highest circulation in Bulgaria, although data on circulation in not entirely reliable. The group also controls a leading TV station and a number of other outlets. There have been persistent allegations that the group was created with loans from a bank that handles the financing of state owned enterprises, but these allegations have not triggered a review by the anti-monopoly commission or other relevant bodies for unlawful state aid or illegitimate concentration. According to its competitors, the group also controls some 80 percent of the printed press distribution in the country.[8]

The official owner of NBMG is Irena Krasteva, the former director of Bulgaria's national lottery. Krasteva's son, Delyan Peevski is a parliamentary deputy from the Turkish ethnic minority party, a minor coalition partner in the 2005-09 Bulgarian government. The NBMG has been criticised for its consistently positive coverage of the last two governments.[9]

Bulgaria has three national public TV channels: BNT1, BNT2, and the worldwide satellite channel TV Bulgaria. Since 2000, there are also private commercial TV channels that are broadcasted terrestrially nationwide: BTV, NovaTV and Pro.BG. National public television has 4 regional channels in Varna, Rousse, Plovdiv, and Blagoevgrad. As of 2006 there were 196 cable and satellite TV programs, and 42 towns had local TV operators and private TV channels. In addition, Bulgarian citizens have access to numerous foreign programs via satellite and cable. Despite the large number of registered programs, however, the national market for both radio and television is relatively concentrated.

Three of Bulgaria's radio stations have national coverage: the two public radio programmes Horizont and Hristo Botev of the public radio operator Bulgarian National Radio (BNR), and the private Darik radio. In general, Bulgaria's largest cities, especially Sofia, enjoy much greater diversity of programming than smaller cities. Just 42 of the 240 towns in the country have local radio programs, but the 9 towns with a population over 100,000 host a total of 115 local radio stations. There are also 18 radio networks which broadcast in the major towns.

Professional organizations and NGO activities play an important role in the development of Bulgarian media. Among the country's most important journalistic associations are the Media Coalition and the Free Speech Civil Forum Association. The Journalists Union, a holdover from the communist era, is attempting to reform its image. More than half of the journalists in Bulgaria are women. The largest publishers are united in their own organizations, such as the Union of Newspaper Publishers. Of the few NGOs that work on media issues, the most important is the Media Development Center, which provides journalists with training and legal advice.

Assessments of Bulgaria's media environment by international organizations have chronicled a tumultuous 5-year period, characterized by sharp improvements and declines, but with a constant downward trend relative to the performance of other EU states.[10] In 2011, two incidents drew international attention to dangers facing media professionals, though the interpretations placed upon them vary greatly. In February a small bomb went off at the entrance of one of the newspapers, Galeria, which is known for its criticism of the GERB government. In October, during the election campaign, the car of the journalist and television presenter Sasho Dikov was blown up in front of his apartment. Dikov was also known for his support of the political opposition. Investigation of both cases was ongoing at year's end. Some have interpreted the bombings as a message intended to threaten independent journalists, while others view the attacks as attempts to implicate the government, or draw attention to its incompetence in investigating the crimes. One issue which was striking in both of the cases was the theatricality of the incidents, which were staged to have maximum public effect.

Local Democratic Governance:

The municipality is the principal local governance body in Bulgaria. The constitution envisages the possibility of an intermediate (regional) level of self-government, but so far parliament has not chosen to adopt the laws necessary for its formation. Under the constitution, the municipalities are legal persons with rights to own property, transact, budget, set local tax rates, define and set local fees, and issue debt within limits specified by law. Since the 1990s, the process of decentralization has proceeded, but very slowly. Much is still controlled at the central level, especially with regard to budgeting and regional development, where the respective ministries and parliament continue to have the final word.

The local elections of October 23 were the first elections held concurrently with presidential and vice presidential elections. This decision put a significant strain on the election administration and led to delays in the announcement of results in some municipalities. Turnout was relatively high at about 51 percent during the first round and 54 percent during the second.[11]

Mayoral and municipal polls brought victory after victory to GERB candidates, driving out or swallowing up small, locally-focused political formations with the potential to enter the municipal councils and become important political stakeholders at the local level. The second largest number of victories went to BSP, strengthening the perception that Bulgarian politics are slowly returning to a two-party system. A side-effect of this development is the smaller emphasis on vote-buying than in previous elections, which may also be attributed to somewhat more effective prevention efforts, including several heavily publicized arrests for related offenses before the elections began. In fact, during the 2011 local elections for the first time the national media reported that certain people and groups, who traditionally sell their votes, complained that there were no buyers. Nevertheless, in many municipalities there were formal appeals against the pronounced election results, leaving the final decision up to the judiciary.

In general, Bulgarian municipalities are too small and poor to make a significant difference in the lives of their citizens through their own resources and decision-making capacity. The development needs of Bulgarian society, which are specific to regional and local circumstances, clearly call for the increased involvement and effectiveness of regional self-governments. Increasing the size of the average municipality (and its resource base) through community mergers could possibly remedy the situation, as might the introduction of an intermediate level of self-government that would then allocate resources on a regional level. The second option is particularly relevant to the disbursement of European Union (EU) funds targeting cohesion and development. Planning for the 2014-2020 EU financial framework began in 2011 and will involve the municipalities in the preparation of strategies for regional operating programs.

When negotiating with the state and the EU, Bulgarian municipalities are represented by the National Association of Municipalities in the Republic of Bulgaria (NAMRB). This is an important organization in the Bulgarian local governance context, since it provides a forum for local governments to voice their concerns, and also provides a venue for sharing best practices and improving administrative capacities. A similar role is played by various non-government organizations specializing in aiding local governments and improving their capacity.

The budgets of Bulgaria's municipalities have suffered significant cuts since the beginning of the global economic crisis of 2008.[12] As a result of austerity measures, many local governments lack the funds to delivery basic services to their residents. Economic recovery and improved access to EU funds for municipalities would help to remedy this problem.

Judicial Framework and Independence:

Basic rights such as the freedom of expression, of association, and of religious beliefs, as well as the rights to privacy, property and inheritance, and economic initiative and enterprise, are enshrined in the constitution, further defined and regulated in national legislation, and generally protected in practice. The most frequently criticized problems in Bulgaria's court and penal system are discrimination against the Roma minority and certain religious beliefs, abuse of the rights of suspects, and significant delays in judicial decision-making. By the summer of 2011, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) had received 700 complaints about significant delays of judicial decisions in Bulgaria's court system, and 130 decisions regarding the complaints were still pending. In May, the ECHR strongly criticized Bulgaria's judicial backlog, and gave the country one year to remedy this "systemic problem."[13]

Inefficiency and corruption within the judiciary are considered a major stumbling block in Bulgaria's battle against high-level corruption and organized crime. Throughout 2011, tensions grew between Interior Minister Tsvetan Tsvetanov and the minister of the judiciary over the low conviction rate in cases of high-level corruption and organized crime. Tsvetanov attempted to use the courts as scapegoats for existing structural problems, issuing several public statements attacking the judicial system in Bulgaria.[14] Suspicions that Tsvetanov's actions placed improper pressure on the independence of Bulgarian courts prompted the European Association of Judges (EAJ) to initiate a fact-finding mission in late January. In July, the EAJ found that Tsvetanov's persistent threats against Bulgarian judges jeopardized the independence of the justice system, violated European standards for the rule of law and unwarrantedly discouraged already fragile public confidence in the Bulgarian justice system.[15]

A controversial proposal to set up specialized courts for prosecuting organized crime passed into law during the last days of 2010 after much heated debate. The law calls for the establishment of specialized courts which will be more immune to pressure from organized criminal groups in court proceedings than ordinary judges. Various changes were introduced into the draft law after consultations with the Venice Commission in order to comply with EU standards. Nevertheless, the new law was challenged in a constitutional court in February 2011, which postponed the establishment of the special courts until January 1, 2012.

The Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) administers the judicial system and is responsible for all judicial appointments. In the summer of 2011, one of the SJC's proposed appointments to the specialized courts came under harsh criticism because the appointee had previously been suspended in a disciplinary action related to "trade in influence." Since 2009, the incumbent SJC has been repeatedly accused of practicing cronyism with regard to senior judicial appointments. The non-competitive, non-transparent character of senior appointments made in 2011 triggered widespread calls for reform of the judicial system and resignation of the incumbent SJC. In response, the minister of justice initiated consultations with civil society on the reform agenda and basis for eventual constitutional amendments.

Another controversial judicial reform intended to streamline organized crime and high-level corruption cases concerns the confiscation of illegally acquired assets prior to conviction. The sixth revised draft of the law on non-conviction based civil confiscation was adopted by the government in May 2011 and approved by the relevant parliamentary committee in June 2011. On 8 July 2011 the draft law was rejected by parliament, but will return to the agenda in 2012. Critics of the law have raised the issue that in an economy with a very large gray sector, the definition of "illegally acquired assets" could be dangerously broad, and affect any number of Bulgarian households. The law also risks becoming a tool for the government to put pressure on the political opposition. If passed, the law is very likely to be brought before the Constitutional Court.

Corruption:

Each branch of Bulgaria's government has a specialized anticorruption body, and there are inspectorates for dealing with allegations of corruption, conflicts of interest, and abuse of power. Financial disclosure, in particular, has captured the public's attention since the beginning of the economic crisis, and financial declarations of officials are carefully scrutinized in the media. Nevertheless, the country's fight against corruption lacks coordination between different units, as well as clearly defined responsibilities and expectations.

Corruption-related scandals occurred throughout the year. A troubling example took place in the beginning of 2011, when wiretaps of telephone conversations between senior officials – including the prime minister, a deputy prime minister and the head of the customs office – were leaked to the press, revealing that senior politicians may have impeded investigations into the operation of certain businesses. Although the authenticity of the recordings and transcripts was never officially proven, some of the participants in the wiretapped conversations confirmed that they had taken place.[16] The leaking of this information to the press also damaged the image of the minister of interior, who had ordered the wiretaps, because it demonstrated the ministry's lack of control over confidential surveillance material.

The gradual decline in everyday corruption evident in 2010 continued in 2011. A survey by the Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD)[17] indicates a gradual decline in the proportion of people pressured into committing corrupt acts. Given a lack of dynamic change in the tax base, increasing tax revenues indicate a slight decline in tax evasion, which is inherently linked to corruption and the grey economy. The introduction of more electronic and automatic services for interacting with administrative offices has decreased opportunities for certain types of corruption, such as petty bribery.

Opinion data for 2011 suggest that the public is still deeply concerned with the phenomenon of corruption, and highly intolerant of such practices.[18] Concerns about Bulgaria's inability to combat organized crime also prompted the European Commission (EC) to issue warnings in 2011 about the large number of acquittals in high-profile corruption cases.[19] Ultimately, the persistence of organized crime has resulted in the EC's decision to delay talks on Bulgaria's entrance into the Schengen zone. Despite the EC's insistence that Bulgaria step up its efforts to combat organized crime, the establishment of a Special Criminal Court intended to try individuals involved in organized crime was further postponed until 2012.[20]

Improvements to procedures for the public tendering of major, EU-funded infrastructure projects continued from the previous year and more procedures have been finalized. As a result, the levels of EU funds absorption have reached record levels. However, the European Bank Coordination Initiative noted that by the beginning of 2011, of all EU member states, Bulgaria had absorbed the least amount of EU funds (15 percent) made available by the European Regional Development Fund, European Social Fund and Cohesion Fund in the Financial Perspectives 2010-13.[21]

In 2011 Bulgaria's economy continued its slow recovery from the global economic slump of 2009, but growth is still lagging compared to the years before the crisis. This is largely due to serious difficulties in Bulgaria's major EU partners, especially its southern neighbor Greece, whose crisis has direct and indirect repercussions for Bulgaria. Nevertheless, government pressure on the economy – which increased in 2010 to compensate for a reduction in tax revenues brought on by the economic crisis – eased in 2011. Though the government continues to run arrears in its payments to the private sector, its fiscally conservative approach appears to be gradually stabilizing the budget situation. The projected budget for 2012, proposed by the government in late October, reflects a political will to decrease the level of redistribution of national income through the next year.

Author:

Georgy Ganev

Georgy Ganev is program director for economic research at the Center for Liberal Strategies, a nonprofit think tank based in Sofia.

Daniel Smilov

Daniel Smilov is program director for political and legal research at the Center for Liberal Strategies, a nonprofit think thank based in Sofia.

Antoinette Primatarova

Antoinette Primatarova is program director for European Studies at CLS-Sofia.

Notes:

[1] Election results available through the website of the Central Electoral Commission of Bulgaria, http://results.cik.bg/tur2/prezidentski/index.html (in Bulgarian).

[2] "Кметските избори в Плевен са законни, реши съдът" [Mayoral elections in Pleven were lawful, says court], Dnevnik, 29 December 2011, http://www.dnevnik.bg/izbori2011/2011/12/29/1736250_kmetskite_izbori_v_pleven_sa_zakonni_reshi_sudut/ (in Bulgarian).

[3] Constitutional Court of the Republic of Bulgaria, "РЕШЕНИЕ No. 12, София, 13 декември 2011 г. по конституционно дело No. 11 от, 2011" [Decision No. 12, 13 December 2011, on Constitutional Case No. 11 of 2011], http://www.constcourt.bg/Pages/Document/Default.aspx?ID=1582 (in Bulgarian).

[4] The Government of Bulgaria, Justice Department, http://www.justice.government.bg/ngo/search.aspx (in Bulgarian).

[5] Informational Portal of the Nongovernmental Organizations in Bulgaria, http://www.ngobg.info/bg/index.html (in Bulgarian).

[6] "Управлението на съдебната система е в криза, министър Маргарита Попова свика Обществения съвет," [The management of the judicial system is in crisis, Minister Margarita Popova convened the Public Council], Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, 21 June 2011, http://www.bghelsinki.org/bg/novini/bg/single/upravlenieto-na-sdebnata-sistema-e-v-kriza-ministr-margarita-popova-svika-obshestveniya-svet/ (in Bulgarian).

[7] See, for example, the BLUELINK Citizens' Action Network, http://www.bluelink.net/ (in Bulgarian).

[8] Kristina Patrashkova, "Журналисти от Европа: Започваме разследване на медийния монопол в България!" [Journalists from Europe start and investigation of media concentration in Bulgaria], 24 Hours, April 7, 2011 http://www.24chasa.bg/Article.asp?ArticleId=847061 (in Bulgarian).

[9] "Близка до банкера Цветан Василев фирма купи 50% от НУРТС" [A Company Close to Tsvetan Vassilev is Buying 50% of NURTS] Drevnik, 7 April 2010, http://www.dnevnik.bg/biznes/2010/04/07/884058_blizka_do_bankera_cvetan_vasilev_firma_kupi_50_ot_nurts/ (in Bulgarian). See also Dimitar Peev, "За връзката между парите на данъкоплатците, Корпоративна банка и 'Нова българска медийна група" [On the Relation between the tax payers, NBMG and Corporate Bank], PR & Media Novini, 22 May 2012, http://prnew.info/tag/nova-bylgarska-mediina-grupa/page/4/ (in Bulgarian).

[10] Reporters Without Borders, Press Freedom Index 2010, http://en.rsf.org/press-freedom-index-2010,1034.html.

[11] Voter turnout was approximately 51 percent during the first round and 54 percent during the second. See Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe/Office Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), Limited Election Observation Mission Republic of Bulgaria – Presidential and Municipal Elections, Second Round, 30 October 2011. Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions (Sofia: OSCE, October 2011), http://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/Bulgaria/84601.

[12] Data from the Ministry of Finance indicate that nominal municipal expenditures have decreased by more than 20 percent between the beginning of 2009 and the end of 2011. Monthly data available at http://www.minfin.bg/bg/statistics/5.

[13] "ECHR: Bulgaria must address 'systemic' judicial problem," SETimes, 11 May 2011, http://www.setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2011/05/11/feature-01.

[14] Concerns with regard to these attempts have been expressed by Gabriela Knaul, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, during her visit to Bulgaria in May 2011.

[15] "International Experts: Bulgarian Interior Minister Erodes Justice System Credibility," Novinite, 16 May 2011, http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=128291.

[16] Information was gathered from various interviews in Bulgarian media.

[17] A portion of the data have not been published and have been obtained directly from the CSD.

[18] Eurobarometer Poll, Eurobarometer Poll 76.1: Attitudes of Europeans towards corruption, 9/2011, September 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_374_fact_bg_en.pdf.

[19] Pauline Moullot, "The Schengen Zone: Another Symptom of the EU Dysfunction," World Policy Blog, 21 October 2011, http://www.worldpolicy.org/blog/2011/10/21/schengen-zone-another-symptom-eu-dysfunction.

[20] Clive Leviev-Sawyer, "The Politics of Crime," The Sofia Echo, 15 July 2011, http://www.sofiaecho.com/2011/07/15/1123913_the-politics-of-crime.

[21] The European Bank Coordination ("Vienna") Initiative, The Role of Commercial Banks in the Absorption of EU Funds Report by the Working Group, (Brussels: EBCI, 16-17 March 2011), http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/articles/financial_operations/pdf/report_eu_funds_en.pdf.