World Refugee Survey 2008 - Turkey

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - Turkey, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50d776.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

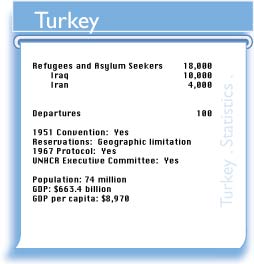

Turkey hosted about 18,000 refugees and asylum seekers, including about 10,000 Iraqis, nearly 4,000 Iranians, over 1,500 Somalis, more than 900 Afghans, and about 1,000 from various other countries. Estimates of the actual number of Iraqis, mostly Chaldean Catholics, ranged from 10,000 to 20,000. About 300 Iraqis arrived each month as of mid-July.

Refoulement/Physical Protection

Turkey forcibly repatriated as many as 75 and deported to third countries at least 123 asylum seekers it had apprehended after they attempted to leave the country, and made no attempt to assess their opportunities for protection.

In February, authorities deported three Sri Lankans from Istanbul's Ataturk airport and two Iranians in March, without allowing them to apply for asylum. In June, for failing to register with police, authorities detained and deported an Iranian refugee whom the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had recognized, while he was awaiting resettlement. In July, Ayvalik police refused to accept the asylum applications of 51 Afghans and likely deported them; their whereabouts remained unknown. Also in July, authorities deported three Baha'i Iranian refugees although they had requested asylum and UNHCR had instructed police to accept their applications. In August, Turkey expelled five UNHCR-recognized Iranian refugees to northern Iraq, without notifying the agency. Iraqi authorities arrested them immediately upon arrival and detained them in Erbil for nearly a month. Also in August, authorities deported six Eritrean women from a Hatay Province "foreigners' guesthouse" – equivalent to a detention center – who had asked for asylum. In November, authorities deported an Iranian refugee from the foreigners' guesthouse in Ankara despite his having an open file with UNHCR.

Authorities rejected the claim of one Iraqi whom UNHCR had recognized and repatriated him. In July, Turkey forcibly repatriated 135 Iraqis it arrested for attempting to leave the country irregularly, even though some had sought asylum. Subsequently Turkey agreed to screen with UNHCR persons of other nationalities it had arrested in the same incident.

Turkey did not separate and screen asylum seekers from the migrants it interdicted, and ignored UNHCR's recognition of others. Turkey refused to accept Iraqi refugees entering from Syria and insisted that UNHCR advise them to return. The Government told UNHCR that some 100 asylum seekers (mostly Iranians and Iraqis) and nearly 40 refugees (22 Iraqis and 15 Iranians) withdrew their applications and spontaneously returned to their countries.

In January, a Nigerian asylum seeker held in detention at Istanbul airport, who refused to board a plane to Nigeria, reported severe physical punishment at the hands of police who cuffed, gagged, and kicked him to make him comply. In April, police raided an Istanbul house where officers beat, choked, and robbed a Congolese asylum seeker. In May and June, at Kirklareli Osman Pasa foreigners' guesthouse, police beat asylum seekers on the soles of their feet on at least 10 occasions. A woman at Zeytinburnu guesthouse reported that an officer held her crying daughter high over a windowsill and threatened to drop her.

In August, in what a court decreed was possibly an intentional killing, Festus Okey, a Nigerian refugee, died at the Beyoglu police station, Istanbul, while in detention on charges of drug use. The accused police officer remained on duty, even as important photographic and material evidence went missing. At the beginning of October, Turkey's Parliamentary Human Rights Commission formed a subcommission to investigate Okey's murder. The case went to the highest criminal court in November and the next hearing was set for May 2008.

Around 65 asylum seekers and refugees who had registered with UNHCR reported suffering sexual and gender-based violence while in Turkey, but only 20 complained to authorities. At UNHCR's request, the Ministry of Interior (MOI) moved seven of them to the country's only voluntary guesthouse specifically for refugees, in Yozgat Province. An Afghan asylum seeker died when her husband stabbed her after authorities rejected her claim. In December, nearly 50 refugees drowned after their boat capsized near Izmir.

In April 2008, in Sirnak Province, at the Iraqi border, authorities forced 18 Iranians and Syrians including 5 UNHCR-recognized Iranian refugees to swim across a river to Iraq. Four persons drowned in the strong current, including one of the refugees. Authorities had arrested them earlier for attempting to enter Greece.

Asylum seekers had to submit parallel applications to MOI and UNHCR. Turkey granted only temporary asylum to non-European refugees, but ethnic Turks, like Iraqi Turkomen, were free to stay, as per the 1934 Law on Settlement. In February, UNHCR's Istanbul office ceased registering asylum seekers, so applicants had to travel to its offices in Ankara or Van. UNHCR refugee status determinations took eight months to over a year. For those the agency recognized as refugees, it sought resettlement to third countries. Appeals and re-openings of cases could take years. Only applicants with legal counsel from one particular rights group had access to UNHCR's detailed reasons for rejecting applicants. The rest only received letters checking off general categories of reasons for denial.

UNHCR began recognizing some individuals who had fled generalized violence under its "extended mandate," mostly Somalis, but some from Côte d'Ivoire and Sudan as well. This amounted to a recommendation of subsidiary protection, which Turkish law did not recognize, so it did not afford protection from arrest or deportation.

Upon registration, UNHCR directed applicants to apply with the Foreigners' Police of the province where the Government had assigned them residence. The Foreigners' Borders and Asylum Division of the MOI in Ankara determined, independent of UNHCR, whether applicants had a legitimate need of temporary asylum without meeting them and often disregarded provincial authorities' recommendations. Under Turkish law, it was their decisions, rather than UNHCR's, that carried weight. Applicants could appeal negative decisions within 15 days but the process was secret. They could also appeal in administrative courts and request interim measures to avoid deportation but the courts responded slowly and deportations took place even as courts were considering appeals. A few applicants with lawyers appealed to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). While the ECHR could only return a negative decision to the MOI for reconsideration, it could order the Government to desist from deporting the applicant pending its assessment.

Of the nearly 4,000 asylum claims it received, Turkey granted temporary asylum to fewer than 50 individuals, all of them Iranian, and rejected the 23 applicants whom UNHCR had recognized as refugees.

Turkey was party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Convention) but maintained a reservation on its 1967 Protocol in order to limit to Europeans its obligations under the 1951 Convention. Turkish law protected non-European asylum seekers from refoulement if they "register(ed) their claims without delay; provided valid identity documentation, and received resettlement assistance from UNHCR or directly from resettling countries." The Passport Law of 1950 criminalized entry into Turkey without valid travel documents.

Detention/Access to Courts

Turkey detained 350 refugees and asylum seekers during the year, deporting over 200 of them. At year's end, seven refugees remained in custody, four of them on criminal charges. Turkey restricted UNHCR's access to detainees and restricted lawyers' access to clients in border areas, but refugees could challenge their detention in both Turkish courts and, as a last resort, the ECHR.

Asylum seekers who applied for protection after authorities detained them as illegal entrants effectively remained in administrative detention at foreigners' guesthouses. Claiming they allowed refugees and asylum seekers to reside freely in satellite cities and did not hold them in guesthouses, authorities rejected a request to monitor the facilities.

Officially, Turkey granted refugees and asylum seekers the same political and civil rights as foreign nationals, regarding the freedom to practice their religion, to seek access to court, and to marry and divorce, provided that they had valid identification documents. A Somali refugee couple, however, could not have their marriage recognized because they had no passports and could not prove their former unmarried status. Because Turkey changed its marriage law in 2007, even some municipal and police officials were unaware of the new regulations, which did not require identification documents or proof of single status in the home country from refugees wishing to marry in Turkey.

Any violation of laws against illegal entry and stay subjected applicants to detention and deportation. The law required courts to provide free interpreters.

Temporary Asylum applicants who had registered with authorities and resided in their assigned cities received an asylum seeker identification card and a residence permit from the provincial Foreigners' Police. The first document was free and had no expiry date, but the resident permit cost nearly $300 and was good for only six months. Although there were exemptions for those in financial need, refugees rarely received them. UNHCR-issued certificates, although not legally binding in Turkey, served as identification, which helped refugees and asylum seekers with police and banks.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Although Turkey did not confine refugees and asylum seekers to camps, the Law on Residence and Travel of Aliens in Turkey required them to reside in areas assigned by the MOI. MOI sent all refugees and asylum seekers to 30 satellite cities. Turkey did not allow UNHCR-registered refugees to live for long periods in major cities, forcing most of them to move to the provinces. Many refugees chose to stay illegally in Istanbul without registering with the Government or UNHCR.

Asylum applicants had to register with Turkish authorities without delay and reside in the town closest to their point of entry, unless UNHCR recommended their transfer to the MOI for security reasons. Asylum seekers had to report regularly, even daily, to the local police. Authorities in each city determined the terms of residence, and violators were subject to immediate deportation at the Government's discretion. Asylum seekers and refugees could move freely within their assigned provinces, but had to obtain permission from the provincial Governorate to travel to other provinces. Those who wished to transfer to another satellite city could do so only if they had family members there or if they had a medical condition that was not treatable in their current city of residence.

The authorities termed those who had not applied for asylum escapees and fined them. They further obstructed the resettlement of those who could not pay the fines and residence fees.

Turkey restricted exit permits for refugees and asylum seekers to third-country and family-reunification resettlement cases. Turkey did not issue international travel documents to refugees.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

Turkey's 2003 Law on Work Permits for Foreigners permitted refugees and asylum seekers with valid residence permits to work legally. Authorities granted few to asylum seekers, however. Some were valid for a year, applicable to those who had yearlong residence permits, but because asylum seekers were eligible only for six-month permits, they could work for six months only.

A 1932 law reserved certain professions and activities for Turkish citizens, specifically those in the various service sectors such as health care and medicine, law, and public and private security. The Labor Ministry issued work permits directly to the employer, and Law 4817 provided penalties for illegal foreign workers and their employers. Refugees were unable to work in the provinces, and even informal work opportunities were limited. Officials were more apt to prosecute illegal work in the provinces.

The vast majority of refugees and asylum seekers who worked in the informal sector did not enjoy the protection of labor laws and social security.

Turkish law did not restrict foreigners from investing business capital, but the temporary nature of asylum that non-European refugees received precluded them from engaging in business. While they could open bank accounts by showing documents that identified them as legal residents in Turkey, they did not have the right to hold title to or transfer business premises, farmland, homes, or other capital assets.

Public Relief and Education

Refugees with valid residence permits were eligible for government services. Limited government health services left many refugees without medical attention. Refugees had to apply for medical aid to officers from the foreigners' branch of the police and depended on provincial authorities' discretion and the availability of local Social Assistance and Solidarity Funds. UNCHR contracted with hospitals and pharmacies to provide a small number of recognized refugees with medical services on an emergency basis.

The Turkish Constitution and the 2006 implementation of the1994 Asylum Regulation offered free education to children aged 6 to 14, but only those with legal residence permits could enroll in public schools. The European Union's 2007 Progress Report for Turkey showed that only some 300 out of over 1,000 children of asylum seekers had enrolled in school.

Turkey did not include refugees and asylum seekers in its Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper prepared for international donors or in other development plans.

USCRI Reports

- Europe: European Union Shuts Doors to Refugees and Asylum Seekers; International Community Ignores Chechens' Plight (Press Releases)