World Refugee Survey 2009 - Malaysia

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 17 June 2009 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2009 - Malaysia, 17 June 2009, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4a40d2adc.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

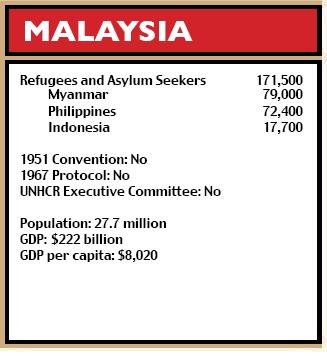

Malaysia hosted around 171,500 refugees and asylum seekers. The largest group were ethnic minorities from Myanmar, mostly Rohingya and Chin but also including Kachin, Arakan, Mon, and others. Malaysia has also hosted 72,000 Filipino refugees since the 1970s.

2008 Summary

Malaysian immigration officials continued to sell deportees to gangs of traffickers operating along the Thailand-Malaysia border. The gangs paid from $250 to $500 per deportee. The traffickers demanded fees of 1,400 to 3,000 ringgit (about $400 to $860) to smuggle the deportees back into Malaysia. They typically sold those who could not pay (perhaps 20 percent), the men onto fishing boats, the women into brothels, and the children to gangs that exploit child beggars.

Malaysia made no changes to its laws or regulations dealing with refugees and asylum seekers during 2008, meaning that arbitrary arrest, detention, and deportation of refugees continued.

During the year, Malaysia deported at least 1,000 refugees and asylum seekers to Thailand, which has in the past returned deportees to Myanmar. It alleged these deportations were voluntary, but because the only alternative was continued detention in poor conditions, this is questionable.

At year's end, Malaysia was holding roughly 400 asylum seekers registered with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), mostly Myanmarese, whom it accused of illegal stay or illegal entry in its detention facilities.

Conditions in detention centers remained abysmal, with overcrowding, poor sanitation, inadequate health care, and abuse all common. The Government did not allow the International Committee of the Red Cross access to the detention centers, but did allow UNHCR limited access to registered refugees and asylum seekers and gave access to staff the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM), the Government's official human rights body, on a case-by-case basis. In December, SUHAKAM announced that 1,535 detainees had died in prisons, rehabilitation centers, and immigration detention between 2003 and 2007. Lack of medical attention was a major cause of death, and SUHAKAM proposed assigning a doctor and medical assistant to each detention center, providing facilities to transfer detainees to hospitals in emergencies, and improve medical monitoring of jails in police stations. During the year, the Government allowed local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to provide some health care to detainees. Officials caned at least 6 refugees (including a minor) for immigration violations during the year, down from 32 in 2007.

During the year, UNHCR registered 17,000 new asylum seekers and made refugee status determinations in 11,000 cases.

During the year, 14 refugees from southern Thailand returned voluntarily, with 106 of the group who fled to Malaysia in 2005 remaining in the Ajil detention center.

In January, officials arrested 10 Myanmarese for forging Thai and Myanmarese passports. They seized fake UNHCR cards, 150 fake passports, 19 fake foreign worker IDs, and 20,000 ringgit (about $5,750). Officials believed they sold passports for $1,000 to $2,000. Officials seized 46 passports from another forgery ring later in the month.

In March, the Prisons Department handed over 11 immigration centers to the Immigration Department. People's Volunteer Corps (RELA) with its 480,000 volunteers became in charge of management of these centers.

Abuses by RELA continued during the year, with reports of rape, beatings, extortion, theft, and destroying UNHCR documents. RELA raided and burned to the ground the camp of 75 Chin refugees from Myanmar in January. They detained 23 of the refugees, and took everything of value in the camp, including cell phones, crafts made for sale, and money.

RELA arrested 200 Rohingya refugees (50 of them children) in a March raid that netted 500 undocumented immigrants.

On April 21, detainees at Lenggeng Immigration Detention Centre rioted, during which an administration building caught fire. Although Malaysian media reported the riot began when 60 Myanmarese detainees were rejected for resettlement to third countries, the incident actually began on April 20 when immigration officers beat nine detainees (six Myanmarese, two Indonesians, and one Pakistani) while interrogating them about a cigarette butt and tobacco found in the detention center. Immigration officers eventually returned the Myanmarese to their cells after they denied smoking, but continued to beat the other three detainees. When the Pakistani crawled out of the room where he was beaten foaming at the mouth, other detainees began to shout and throw objects from their cells in protest. Immigration officers took the Pakistani and two Indonesians away, and a senior RELA official arrived by 10 p.m. to urge the detainees to settle down. The next morning, many of the detainees refused breakfast and announced they were on a hunger strike. By noon, RELA and immigration officers usually on duty had withdrawn from the cellblocks, and some detainees broke out of one block and opened the others. Some detainees stayed in their cellblocks, but others rushed out and a fire soon broke out in an administrative office. Media reports said 100 police, 100 RELA members, and 40 immigration officers restored order.

RELA officials arrested 14 detainees (six Indonesians, three Myanmarese refugees registered with UNHCR, three Myanmarese asylum seekers, one Cambodian, and one documented Vietnamese migrant worker) for possession of dangerous weapons and creating mischief by fire or explosives. Two of the arrested reported being beaten and burned with cigarettes as they were driven away from the detention center. Authorities also transferred all Myanmarese detainees to other facilities, beating them on the way according to detainees. In the wake of the incident, Malaysia announced it would tighten border security to reduce crowding in detention centers.

In April, three Myanmarese refugees received 36-year jail sentences for their 2004 attempt to kill Myanmar's ambassador to Malaysia and burn down its embassy. They had represented themselves after dismissing lawyers provided by the Legal Aid Bureau. In a separate case, a Myanmarese refugee plead guilty to culpable homicide not amounting to murder in the 2006 killling of a 17-year-old refugee in a detention center.

Unknown assailants stabbed and set fire to a Myanmarese refugee in April, killing him.

In May, RELA members arrested a foreign diplomat and held her for two hours, despite her presenting her diplomatic ID. They released her only upon the intervention of her embassy.

Malaysia returned two Chinese Muslims to China at the request of the Chinese government in June.

In June, the Government announced a crackdown on illegal immigrants in the Sabah state, home to more than 70,000 Filipino refugees. The crackdown aimed to deport some 200,000 irregular migrants, who were mainly Filipinos.

As of August, about 35,000 had been deported. By the end of the year, thousands more were deported.

Police arrested four Myanmarese for the murder of a Myanmarese refugee woman in July.

In August, the Government announced that the remaining 25,000 Acehnese holding IMM13 work permits would have to leave the country by January 2009 or be deported.

In August, RELA arrested over 11,000 people, only 500 of whom did not have legal immigration status.

In September, a court ordered a RELA member to pay 100,000 ringgit (about $28,800) to a woman whom he photographed while she was forced to relieve herself in the back of a truck taking her to a detention center.

In October, the Philippines announced that many deported Filipinos had been beaten by Malaysian police and detained in inhumane conditions.

Around 300 Rohingya refugees lost their jobs as car washers in October, after immigration officials threatened their employers with 5,000 ringgit (about $1,440) fines.

In November, Malaysia's high court overturned migrant rights activist Irene Fernandez's 2003 conviction for publishing allegedly false information. She had received a 12-month jail sentence for reporting on poor conditions in detention centers in 1995.

Law and Policy

Refoulement/Physical Protection

The Government has no procedure for granting asylum or registering refugees. UNHCR handles all refugee status determinations in Malaysia and issues plastic, tamperproof cards to those it recognizes as refugees. UNHCR performs individual status determinations for all asylum seekers under its mandate.

Malaysia is not party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, but is party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which obligates it to give protection and assistance to children seeking refugee status and to cooperate with UN assistance to refugee children.

As UNHCR has no presence at the border, most asylum seekers have to travel to Kuala Lumpur for determinations. UNHCR conducts mobile registration exercises in areas with high concentrations of refugees, but many asylum seekers remain unregistered.

The Government continues to permit refugees from the Philippines' Moro insurgency of the 1970s to remain in Sabah State. The Government does not grant them citizenship, however, putting their children at risk of statelessness.

Detention/Access to Courts

In November 2007, the Government announced it was transferring control of the immigration detention centers back to the Immigration Department and that RELA members would be assisting with security in them until it could train full-time staff, perhaps for as long as two years.

UNHCR is usually able to access detention centers, and make several visits during the year. The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, a governmental body, is able to visit detention centers but needs Government approval. The Government does not generally permit the International Committee of the Red Cross, nongovernmental organizations, or the media to visit prisons or monitor conditions. Refugees can challenge their detention if they have legal representation. UNHCR provides those held on immigration violations with volunteer lawyers and often secure their release. Authorities do not permit detainees to make phone calls upon arrest, so they generally have to bribe a police officer to be able to inform anyone of their arrest.

Refugees with UNHCR cards are usually safe from arrest by regular police, although RELA and Immigration officials still detain them. Police still arrests asylum seekers occasionally, as they do not always recognize the letters UNHCR issues asylum seekers. Refugees are subject to prosecution under the 1959 Immigration Act, which make no distinction between refugees and illegal immigrants. Amendments to the Immigration Act in 2002 provides for up to five years' imprisonment, along with whipping up to six strokes, and fines of 10,000 ringgit (about $3,020) for violations.

The Federal Constitution extends its protections for individual liberty to all persons, but creates an exception whereby the 24 hours allowed authorities to bring a detainee before a magistrate become two weeks in the case of an alien detained under the immigration laws.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

There are no camps or segregated settlements in Malaysia, but refugees' and asylum seekers' freedom of movement depends on the acceptance of their documents by Malaysian authorities. Those with UNHCR refugee cards enjoy some freedom of movement and residence.

The Immigration Act prohibits renting housing to illegal migrants. The law generally confines Filipino Muslim refugees to the designated area of Sabah.

In March, the home minister called for the establishment of closed camps for refugees and for UNHCR to administer them.

Refugees do not receive international travel documents except for resettlement.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

Refugees and asylum seekers hold no official legal status and are not permitted to work legally.

In 2005, the Government issued between 32,000 and 35,000 IMM13 work permits to Acehnese migrants and refugees from Indonesia. The permits cost between 162 and 180 ringgit (about $47 and $52), are valid for two years, and are renewable. They do not permit the refugees to engage in trade but do allow them to work, attend school, and live in the country legally. The permits do not tie their bearers to single employers. In 2006, the Government began to issue IMM13 permits to Muslim Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, but stopped amid accusations of bribery and corruption in the issuing process. That leaves some 5,000 Rohingyas holding receipts proving they paid for IMM13 permits without the permits themselves.

The Immigration Act penalizes employers of illegal immigrants with fines of about 10,000 to 50,000 ringgit (about $3,020 to $15,100) or, if they employ more than five, imprisonment from six months to five years and up to six cane strokes.

Foreign workers with legal permits can join unions, but the permits of most foreign workers tie them to single employers, although this is not the case with the IMM13 permits given to Acehnese or Filipino refugees. Workers without legal status generally cannot use the national system of labor adjudication. If employers dismiss foreign workers for any reason, they lose their permits, their legal right to remain in Malaysia, and their right to pursue legal action against abusive employers – despite court requests that the Immigration Department grant them visas to do so.

Malaysia also does not allow refugees to hold title to or transfer business premises, farmland, homes, or other capital assets. The Federal Constitution offers most of its protections from arbitrary deprivation of property to all persons, but reserves protection against discrimination based on religion, race, descent, or place of birth in work, trade, professional, or property matters and the right to form associations to citizens.

Public Relief and Education

Despite its obligations under the CRC, Malaysia does not provide primary education or free health services to most refugee children or asylum seekers – not even those born in Malaysia. Although the IMM13 permits grant parents the right to send their children to public schools, the Government allows them to attend only private schools.

Refugees with UNHCR documents receive medical services at half the standard price for foreigners. Refugees and asylum seekers with HIV/AIDS receive access to free treatment from the public health service. Other than this, authorities provide no medical care, public relief, rationing, or assistance, but do permit independent humanitarian agencies to assist refugees.

Malaysia did not include refugees or asylum seekers in the Ninth Malaysia Plan, the country's primary economic planning document, but it did include them in its National Strategic Plan for HIV/AIDS 2007-2010.