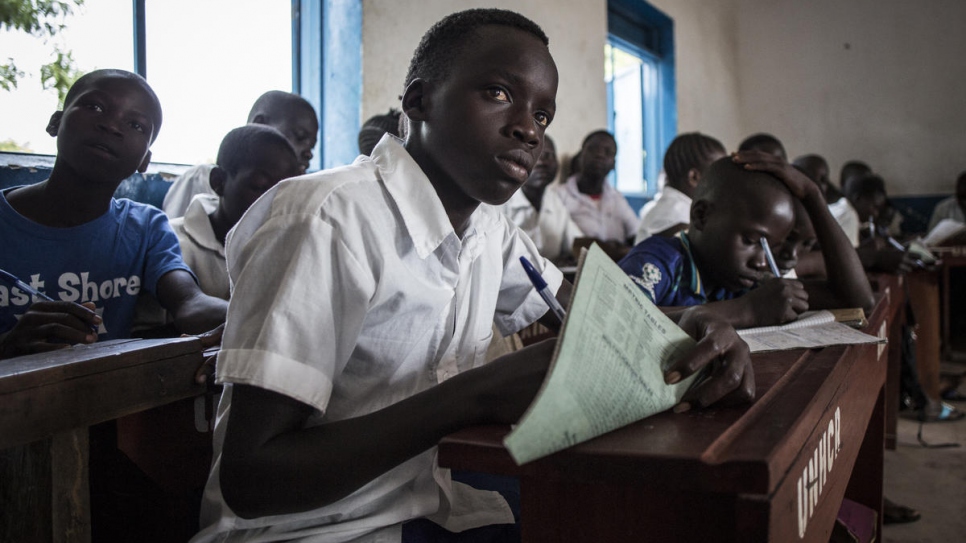

Top of his class and hungry for more, a young South Sudanese refugee battles the odds

On the run from the civil war, a boy named Gift is determined to continue his education. But his ingenuity, brilliance and determination may not be enough to keep him in school.

Gift, 14, reads with a solar-powered lamp he built in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

© UNHCR/John Wessels

Gift, 14, has been top of his class for the past three years. That may not be enough to keep him in school.

“When I grow up, I would like to become a teacher. I would like this job because I like to help those who have less knowledge,” he said of the ambition that has driven him forward against the odds.

Those odds were considerable. Gift fled the war that was ravaging his homeland, South Sudan, a conflict that had claimed the life of his father. Determined to succeed, he learned French from scratch and even designed his own light from spare parts of a broken solar lamp so he could study at night.

Despite all his hard work, a huge cloud hangs over Gift’s future. The talented teenager is in his last year of primary school in the eastern stretches of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) where secondary school places are few and far between.

South Sudanese refugees go back to school in Biringi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Rayan Hindi, producer, camera-editor / Thomas Freteur, camera)

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, helps refugee children such as Gift go to school by providing cash grants that help families to pay fees, and to purchase schoolbooks, supplies and uniforms. But both funds and opportunities are limited, particularly at secondary school level, which means Gift and thousands of other South Sudanese child refugees may have to call a premature halt to their studies.

Gift and his uncle – who became his legal guardian after his father was killed and he lost touch with his mother – sought safety in Biringi settlement, in the DRC, in 2016.

"I had to quit school because of the war. When I found out I was going back to school, it made me happy."

The boy well remembers his first day in Uboko primary school, where 800 local Congolese and refugee children study together after the school was rehabilitated by UNHCR. He was excited and thankful for a new opportunity to learn again.

“The war makes a lot of people suffer – I had to quit school because of the war. When I found out I was going back to school, it made me happy,” he recalled with a smile.

Mastering French, the main language of instruction in the DRC, was achieved by attending language courses provided by UNHCR – with Gift even winning a province-wide spelling contest.

Then he had a practical problem: no electricity meant he had no light by which to study at home at night. His solution? To design his own solar-powered lamp. “I had to build this,” he said, holding out a flimsy light made of three bulbs and a solar battery held together by tape.

As South Sudanese children continue to seek refuge in Congolese territory, the education gap is only increasing. Only 4,400 out of 12,500 South Sudanese children in the DRC have access even to primary education. Until recently, they had no secondary opportunities whatsoever.

In 2019, UNHCR started a small programme to enrol refugees in secondary school. It also helps to construct and refurbish school buildings.

Even so, of the more than 6,000 South Sudanese secondary-age refugees, a staggering 92 per cent still do not go to school.

Gift knows the odds are stacked against him. And he fears he will be regarded as worthless in the eyes of both his host community and his fellow refugees if he cannot get an education. It is vital to both his hopes of becoming a teacher, he says, and of becoming a voice for others in his position.

Yet he simply cannot imagine life without education. “It would be horrible if I couldn’t go to secondary school,” he said. “There should be a way for everyone to study.”

"The alternative to school is waiting around with no clear options for the future."

Ann Encontre, UNHCR’s Regional Representative in the DRC, said there are “extraordinary talents” among the young refugees she has met. “When you talk to them, you see how eager they are to learn.”

Secondary school gives refugee adolescents a sense of purpose, a vision of the person they can become, and the knowledge that will one day help them rebuild their homes, she adds.

“The alternative to school is waiting around, with no clear options for the future. This is why we are doing all we can to keep them in school.”

This story is featured in UNHCR's 2019 education report Stepping Up: Refugee Education in Crisis. The report shows that as refugee children grow older, the barriers preventing them from accessing education become harder to overcome: only 63 per cent of refugee children go to primary school, compared to 91 per cent globally. Around the world, 84 per cent of adolescents get a secondary education, while only 24 per cent of refugees get the opportunity. Of the 7.1 million refugee children of school age, 3.7 million – more than half – do not go to school.