On the Run

Thousands of people in Côte d’Ivoire have been unable to claim nationality until now. Ousmane is one of them.

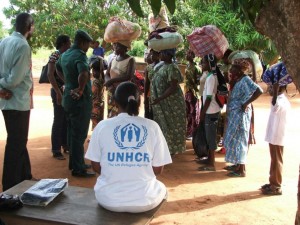

DUÉKOUÉ, CÔTE D’IVOIRE, 7 Novembre 2014 (UNHCR) – When first asked about his past, Ousmane* hesitates, visibly reluctant to talk about it. He has suffered a great deal in his life, and it pains him to recount bad memories. The UNHCR team reassures him repeatedly that we are there to help him and with time, he begins to trust us and agrees to share his story.

His recollections of childhood are hazy – he knows only that he was born in a small village in south-east Côte d’Ivoire, across the border from Ghana, that his mother was a citizen of Burkina Faso and that his father disappeared when he was young.

But when we ask him what his nationality is, he cannot answer. He was not registered at birth because it never occurred to his family that this might be important. Nor does he have any documents that confirm his parents’ identity or prove his own nationality. Neither the Ivoirian nor the Burkinabè authorities recognise him as a national of their country. He is, in a word, stateless.

Stateless people are invisible in the eyes of the law and, as a result, are faced with limited opportunities for formal employment, making them easy targets for human traffickers. Ousmane is no exception. In 1987, when he was only six years old, he was taken from his village by a woman who claimed to be an aunt and sold to a landowner in Gbapleu, about 650km north-west of the capital Abidjan.

Stateless people are invisible in the eyes of the law and are faced with limited opportunities for formal employment because they cannot prove their identity. This makes them easy targets for human traffickers, as illustrated by the case of Ousmane featured in this story.

By the time Ousmane turned 14, he had been the victim of forced labour twice at the hands of people claiming to protect him. He did backbreaking work for years, clearing brush, planting and picking cocoa beans and ploughing fields, and was severely beaten if he complained or was not fast enough. “They would hit me across the face, across the chest, over and over again,” he says, slashing the air with his hands in imitation.

After enduring this suffering for seven years, Ousmane found the strength to escape and flee to his birth village in search of his mother. Since he had no documents of his own, he did what many stateless people, desperate for some kind of legal identity, are forced to do. He got his hands on the consular card of a young Burkinabè man who had recently passed away and used it to cross the country.

Unfortunately, his trip, in which he had invested so many hopes and dreams of being reunited with his family, was only a waste of time and money. Upon arriving in his village, he learned that his mother had died years ago and that his father had disappeared. Ousmane had little choice but to return to Gbapleu, where at least he knew some people.

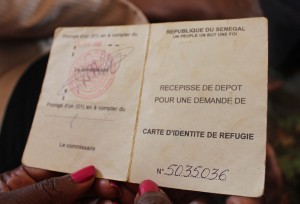

He realised that his lack of documentation was a serious problem – if he was caught using someone else’s identity card, he could face criminal charges – and so he decided to apply for a consular card from the Burkinabè Delegate in Duékoué, one of the main towns in western Côte d’Ivoire. With this piece of identification, he could at least prove that he was recognised by the authorities as a Burkinabè citizen and receive assistance from the Burkina Faso authorities.

However, with no documents to confirm his identity other than a stolen ID card, his application was immediately rejected and he was ostracised by the Burkinabècommunity as a troublemaker. To avoid further persecution, he fled to Duékoué, where we met up with him. He had piled all of his belongings onto the back of his bicycle and was planning to leave the next day, in search of assistance but mostly to escape potential further abuse such as forced labour and being beaten.

Ousmane’s story is common for many stateless people, whose desperate situation makes them extremely vulnerable to exploitation. UNHCR will bring his case to the attention of the Ivoirian and Burkinabè authorities and advocate for concrete measures to be taken to resolve his status, either through the recognition of Burkinabè citizenship or as a stateless person in Côte d’Ivoire entitled to rights, including the right to an identity document.

In the meantime, Ousmane remains stateless and will continue to live on the margins of society, vulnerable, poor and easy to ignore.

*Ousmane’s name has been changed to protect his identity. We also chose not to use his picture for the same reason

Le texte en français:

A ce jour, des milliers d’individus en Côte d’Ivoire sont incapables de revendiquer leur nationalité. Ousmane est l’un d’entre eux. DUÉKOUÉ, CÔTE D’IVOIRE, 7 novembre 2014 (HCR) - Lorsqu’on interroge Ousmane* sur son passé, il commence par hésiter, visiblement peu enclin à en parler. Il a beaucoup souffert dans sa vie, et cela lui coûte de raconter ses mauvais souvenirs. L’équipe du HCR le rassure à plusieurs reprises sur le fait que nous sommes là pour l’aider et, avec le temps, il commence à nous faire confiance et accepte de partager son histoire. Ses souvenirs d’enfance sont flous – il sait seulement qu’il est né dans un petit village au sud-est de la Côte d’Ivoire, près de la frontière avec le Ghana, que sa mère était citoyenne du Burkina Faso et que son père a disparu quand il était jeune. Mais quand on lui demande quelle est sa nationalité, il ne peut pas répondre. Il n’a pas été enregistré à la naissance parce que sa famille n’a jamais pensé que cela pouvait avoir une importance. Il n’a pas non plus de document confirmant l’identité de ses parents ou prouvant sa propre nationalité. Ni les autorités ivoiriennes ni les autorités burkinabè ne le reconnaissent comme citoyen de leur pays. Il est, en un mot, apatride. Les apatrides sont invisibles aux yeux de la loi et, par conséquent, font face à des occasions limitées d’obtenir un emploi formel, ce qui fait d’eux des proies faciles pour la traite des êtres humains. Ousmane ne fait pas exception. En 1987, quand il n’avait que six ans, il a été enlevé de son village par une femme qui prétendait être une tante et qui l’a vendu à un propriétaire terrien à Gbapleu, à environ 650 km au nord-ouest de la capitale Abidjan. Quand Ousmane a atteint 14 ans, il avait déjà été victime de travail forcé à deux reprises aux mains de personnes qui prétendaient le protéger. Il a fait un travail éreintant pendant des années, élaguant la brousse, plantant et récoltant des fèves de cacao et labourant les champs, et était sévèrement battu s’il se plaignait ou ne travaillait pas assez rapidement. « Ils me frappaient sur le visage, sur la poitrine, encore et encore », dit-il, fouettant l’air de ses mains pour illustrer son propos. Après avoir subi ces souffrances pendant sept ans, Ousmane a trouvé la force de s’échapper et a fui jusqu’à son village natal pour retrouver sa mère. Comme il n’avait aucun document à son nom, il a fait ce que beaucoup d’apatrides, au désespoir de trouver une forme légale d’identité, sont forcés de faire. Il s’est procuré la carte consulaire d’un jeune Burkinabè qui était décédé peu avant et l’a utilisée pour traverser le pays. Malheureusement, son voyage, dans lequel il avait mis tant d’espoir et de rêves de retrouver sa famille, n’était qu’une perte de temps et d’argent. En arrivant dans son village, il a appris que sa mère était morte plusieurs années auparavant et que son père avait disparu. Ousmane n’avait pas d’autre choix que de retourner à Gbapleu, où il connaissait au moins quelques personnes. Il a réalisé que son manque de papiers était un problème sérieux – s’il était arrêté alors qu’il utilisait la carte d’identité de quelqu’un d’autre, il serait accusé d’acte criminel – et il a donc décidé de demander une carte consulaire auprès du délégué burkinabè à Duékoué, une des principales villes dans l’ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire. Avec cette pièce d’identité, il pourrait au moins prouver qu’il était reconnu par les autorités comme citoyen burkinabè et recevoir l’aide des autorités du Burkina Faso. Cependant, sans documents pour confirmer son identité autre qu’une carte consulaire volée, sa candidature a été immédiatement rejetée et il a été identifié par la communauté burkinabè comme fauteur de troubles. Pour éviter de nouvelles persécutions, il s’est enfui à Duékoué, où nous l’avons rencontré. Il avait entassé tous ses biens à l’arrière de son vélo et prévoyait de partir le jour suivant, en quête d’assistance mais surtout pour échapper à de nouveaux abus potentiels comme le travail forcé ou être de nouveau battu. L’histoire d’Ousmane est similaire à celle de nombreux apatrides, que leur situation désespérée rend extrêmement vulnérables à l’exploitation. Le HCR portera son cas à l’attention des autorités ivoiriennes et burkinabè et demandera que des mesures concrètes soient prises pour clarifier son statut, soit par la reconnaissance de sa citoyenneté burkinabè soit en tant qu’apatride en Côte d’Ivoire, ce qui lui donne des droits, y compris le droit d’avoir un document d’identité. En attendant, Ousmane reste apatride et continue de vivre en marge de la société, vulnérable, pauvre et facile à ignorer. *Le vrai nom d’Ousmane a été changé pour protéger son identité. Nous avons choisi de ne pas utiliser sa photo pour la même raison.

En fuite