Rihanna Siraj, 15, Ethiopian refugee, attends school in Kakuma refugee camp, Kenya. She is among one million formerly out-of-school refugee students who now go to primary school thanks to the support of the Educate A Child programme. ©UNHCR/Anthony Karumba

This report tells the stories of some of the world’s 7.4 million refugee children of school age under UNHCR’s mandate. In addition, it looks at the educational aspirations of refugee youth eager to continue learning after secondary education, and highlights the need for strong partnerships in order to break down the barriers to education for millions of refugee children.

Education data on refugee enrolments and population numbers is drawn from UNHCR’s population database, reporting tools and education surveys and refers to 2017. The report also references global enrolment data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics referring to 2016.

It’s time to turn the tide

Introduction by Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi meets 7-year-old Syrian refugee Mohammad during a visit to the Father Andeweg Institute for the Deaf (FAID) in Beirut, Lebanon. © UNHCR/Claire Thomas

In early July, I travelled to the Kutupalong refugee settlement in Bangladesh, which has become home to hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees who have fled horrific violence in Myanmar. In a one-room learning centre, with the monsoon rains hammering on the roof, I saw girls and boys learning the basics of reading, writing and maths for just two hours a day, before another group took their place, and then another.

It was heart-rending to watch this faint semblance of the proper schooling to which these young refugees are entitled. But it also made it abundantly clear just how highly they value education. Without it, their future, and eventually the future of their communities, will be irrevocably damaged.

Bangladesh: A first classroom for Rohingya refugee children. Photo ©UNHCR/Adam Dean

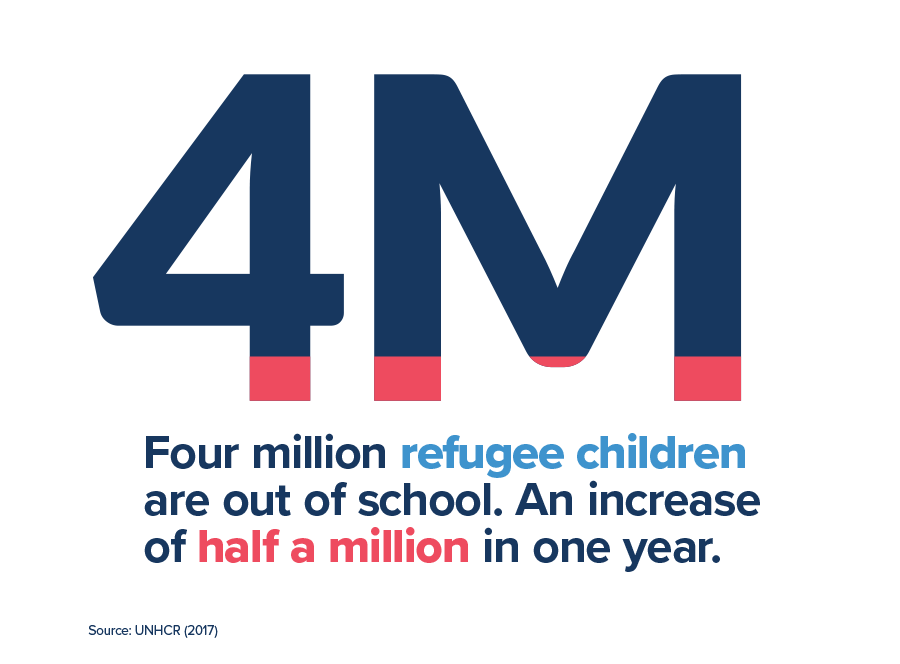

Half of the world’s refugees are children. Of the children who are of school age, more than half are not getting an education – that equates to four million young minds not in school even though they are bursting with potential.

The number of out-of-school refugee children has increased by 500,000 in the last year alone. If current trends continue, hundreds of thousands more refugee children will be added to these disturbing statistics unless urgent investment is made.

As part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the members of the United Nations pledged to ensure an “inclusive and equitable quality education” and to promote “lifelong learning opportunities for all”. And in the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2016, governments pledged to share responsibility for the world’s refugees and to improve access to education for refugee children.

These were important commitments. But they will ring hollow to young refugees unless and until they experience real change and are given the same opportunities to go to school as others. It is time to honour those pledges and turn the tide, as detailed in our annual report on refugee education.

The same violence and persecution that uproots people from their homes, destroys stable family lives and forces many into poverty can also damage children’s physical, psychological and developmental well-being. As the world’s refugee crises deepen and multiply, children are often the most affected.

Photo © UNHCR/Houssam Hariri

“I loved it from day one. I missed two years of schooling because of the war.”

Moaed, 13, Syrian refugee, attends Bar Elias School in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. It is one of around 350 schools in Lebanon operating a second shift to increase the number of places available for refugee students. Afternoon shifts have allowed more than 150,000 refugee children to enrol in school in Lebanon.

But children are extraordinarily resilient. By learning, playing and exploring, they find ways to cope, to progress and, if given the opportunity, to thrive. Today, education is fundamental to the way we at UNHCR think about every refugee emergency. Why? Because refugees now spend many years, even decades, in exile – a period that often extends over an entire childhood and beyond.

Many children and young people are displaced several times before they cross a border and become refugees. For children whose lives have been disrupted in this manner, school is often the first place they start to regain normality – safety, friendship, order, peace. Regardless of their nationality or legal status, or that of their parents, children have the right to the academic and co-curricular activities that will enable them to prosper.

But two hours of basic education, as I witnessed in Kutupalong, is not enough. Children need a proper curriculum all the way through primary and secondary school, resulting in recognized qualifications that can be their springboard to university or higher vocational training.

For that to happen, refugee children need to be included in the national education systems of their host countries – systems that are regulated, monitored and updated. In Bangladesh, many Rohingya girls and boys are going to school for the first time. This is welcome progress, but the fact that they are not following any formal curriculum, and the teachers are often untrained, severely limits their potential.

Rohingya refugee children collecting firewood on the edge of the forest in Kutupalong refugee settlement, Bangladesh. Many Rohingya children miss out on school because of household chores, social pressures, early marriage and a lack of access to formal education. © UNHCR/Roger Arnold

Yet the power of school runs deeper than academic qualifications. Education is a way to help young people heal, but it is also the way to revive entire countries. Allowed to learn, grow and flourish, children will grow up to contribute both to the societies that host them and to their homelands when peace allows them to return. That is why education is one of the most important ways to solve the world’s crises.

In following the fortunes of young refugees who have had the opportunity of education, we have seen some pursue their dreams of becoming surgeons, pilots, lawyers, statisticians, journalists, community leaders, molecular biologists – and the teachers of the next generations.

Madina, 16, Afghan refugee living in Brussels, Belgium, dreams of setting up a school for girls in Afghanistan. “I want all the girls in Afghanistan to know that they can do anything boys can do.’’ © UNHCR/Humans of Amsterdam/Fetching_Tigerss. Extract from story by @humansofamsterdam

But we have also seen dreams broken and thwarted. Less than a quarter of the world’s refugees make it to secondary school, and just one per cent progress to higher education. Developing regions host 92 per cent of the world’s school-age refugees, where schools are often woefully under-resourced. These governments need support to include refugee children in national education systems – as some of them are indeed striving to do – and to expand the infrastructure that is needed to bring this about.

We cannot build a future by shunting refugee children into a parallel system of schooling that relies on outdated materials, makeshift classrooms or untrained teachers. We cannot improvise an education and imagine that this is good enough.

Humanitarian organizations, governments and the private sector must come together to increase funding for education and to design more innovative and sustainable solutions to support refugees’ particular educational needs. We must build on the promise of the New York Declaration and start turning words into deeds. The global compact on refugees, to be adopted by the General Assembly later this year, sets out practical arrangements aimed at achieving just that – with the aim of enhancing refugees’ self-reliance and easing the burden on host countries.

This worldwide effort to transform the lives of refugees must include a concerted drive to improve educational opportunities and resources. In doing so, we will restore their futures and enrich our world.