The Most Important Thing

Photography by Brian SokolIf conflict tore your country apart and forced you to run for your life, what would you bring with you?

The Most Important Thing

Photography by Brian SokolIf conflict tore your country apart and forced you to run for your life, what would you bring with you?

They walked for days through jungles and mountains or braved dangerous voyages across the river to reach safety. Here, 11 Rohingya refugees present the things that mean most to them.

Photographer Brian Sokol, working with UNHCR staff around the world, has posed the same question to hundreds of people who have been forced to flee their homes. What’s the most important thing you brought with you?

The resulting photo project, “The Most Important Thing,” provides surprising and thoughtful responses. In this instalment, Sokol focuses on Rohingya refugees who have fled to Bangladesh.

The latest exodus began on 25 August 2017, when violence broke out in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. More than 700,000 Rohingya have arrived in Bangladesh since then. Most are women and children; others are older people who need additional aid and protection. Many speak of extreme violence. Some still possess the items they took when they fled, having saved them as reminders of loved ones or of a way of life they have left behind.

Past subjects of this project have included Malian refugees in Burkina Faso; Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan; Sudanese in South Sudan; and Central Africans and Angolans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Photographer Brian Sokol, working with UNHCR staff around the world, has posed the same question to hundreds of people who have been forced to flee their homes. What’s the most important thing you brought with you?

The resulting photo project, “The Most Important Thing,” provides surprising and thoughtful responses. In this instalment, Sokol focuses on Rohingya refugees who have fled to Bangladesh.

The latest exodus began on 25 August 2017, when violence broke out in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. More than 700,000 Rohingya have arrived in Bangladesh since then. Most are women and children; others are older people who need additional aid and protection. Many speak of extreme violence. Some still possess the items they took when they fled, having saved them as reminders of loved ones or of a way of life they have left behind.

Past subjects of this project have included Malian refugees in Burkina Faso; Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan; Sudanese in South Sudan; and Central Africans and Angolans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Noor

“If we die, we’ll die together.”

In late August 2017, as nearby homes burned and exploded, Noor sprinted into the darkness with her six children. “If we die, we will die together,” she told them. As they ran empty-handed, neighbours fleeing next to them were shot and killed. Suddenly, there was a loud blast and Noor turned around to find seven-year-old Roshida* lying on the ground. Several feet away lay her daughter’s foot and the lower half of her leg. Her chest barely rose and fell, and a whisper of breath escaped through her mouth. It took a month, going from village to village, before they reached Bangladesh. “It was so difficult that we have no words to begin to explain to you,” says Noor. “The greatest loss we have suffered is her leg. And the most important gift that we have been given is her life – is the sound of her voice.”

Noor

“If we die, we’ll die together.”

In late August 2017, as nearby homes burned and exploded, Noor sprinted into the darkness with her six children. “If we die, we will die together,” she told them. As they ran empty-handed, neighbours fleeing next to them were shot and killed. Suddenly, there was a loud blast and Noor turned around to find seven-year-old Roshida* lying on the ground. Several feet away lay her daughter’s foot and the lower half of her leg. Her chest barely rose and fell, and a whisper of breath escaped through her mouth. It took a month, going from village to village, before they reached Bangladesh. “It was so difficult that we have no words to begin to explain to you,” says Noor. “The greatest loss we have suffered is her leg. And the most important gift that we have been given is her life – is the sound of her voice.”

Omar, 102

“If hadn’t had my lati, I would have crawled to Bangladesh.”

The most important thing that Omar, who is 102 and blind, brought with him is his lati or walking stick. He and his fellow villagers fled their homes after witnessing a horrific attack on the neighbouring village and several brutal murders. Omar found his way by following the voices of the other refugees and using his lati. At one point, after hopping off of a fisherman’s boat, he was lost in a mangrove forest for seven hours, up to his neck in water. He weeps as he recounts the harrowing tale. Eventually he found his way to shore but was exhausted after the ordeal. Omar says leaving his village was the hardest thing he has ever done, but now that he is safe and reunited with his family, he is happy and at peace. “If you laugh, others will laugh with you. And if you stop laughing, you will die.”

Omar, 102

“If hadn’t had my lati, I would have crawled to Bangladesh.”

The most important thing that Omar, who is 102 and blind, brought with him is his lati or walking stick. He and his fellow villagers fled their homes after witnessing a horrific attack on the neighbouring village and several brutal murders. Omar found his way by following the voices of the other refugees and using his lati. At one point, after hopping off of a fisherman’s boat, he was lost in a mangrove forest for seven hours, up to his neck in water. He weeps as he recounts the harrowing tale. Eventually he found his way to shore but was exhausted after the ordeal. Omar says leaving his village was the hardest thing he has ever done, but now that he is safe and reunited with his family, he is happy and at peace. “If you laugh, others will laugh with you. And if you stop laughing, you will die.”

Nuras, 25

The most important thing Nuras brought with her into exile from Myanmar is a baby she found while fleeing an attack on her village.

After her neighbours were murdered, 25-year-old Nuras and her four children were chased and fired at as they fled. While running, Nuras heard a baby crying and coughing nearby. She found him near the bodies of two slain Rohingya people, in a dry and faraway rice paddy, flailing his arms. “Maybe Allah has given me a gift to protect me and my children during this journey,” she thought. With the infant in her arms, Nuras walked with her children all day and eventually arrived at the Bangladeshi border, where her husband, who had gone ahead, waited. She searched the site for the baby’s family but when no one claimed him, she and her husband decided to name him Mohammed Hasan, after the prophet Mohammed’s grandson. They hope that Mohammed will grow into a strong man who will become a religious teacher one day.

Nuras, 25

The most important thing Nuras brought with her into exile from Myanmar is a baby she found while fleeing an attack on her village.

After her neighbours were murdered, 25-year-old Nuras and her four children were chased and fired at as they fled. While running, Nuras heard a baby crying and coughing nearby. She found him near the bodies of two slain Rohingya people, in a dry and faraway rice paddy, flailing his arms. “Maybe Allah has given me a gift to protect me and my children during this journey,” she thought. With the infant in her arms, Nuras walked with her children all day and eventually arrived at the Bangladeshi border, where her husband, who had gone ahead, waited. She searched the site for the baby’s family but when no one claimed him, she and her husband decided to name him Mohammed Hasan, after the prophet Mohammed’s grandson. They hope that Mohammed will grow into a strong man who will become a religious teacher one day.

Jamir, 15

“If I’m in a crisis, maybe no one will come to help me – but Shikari will always come.”

Fifteen-year-old Jamir* reaches toward his dog Shirkari, outside of the small shop his family run in a refugee settlement in southern Bangladesh. “Shikari is the most important thing that came from Myanmar, because he is my best friend and my protector.” says Jamir. Jamir, whose family fled Myanmar 28 years ago, was born in the settlement and has never set foot in Myanmar. He first saw the dog last autumn, shortly after it arrived from Myanmar with a Rohingya refugee. When the animal approached him and sniffed his foot, Jamir threw a piece of food. After the dog sprang into the air to catch it, Jamir named him Shikari, which means ‘hunter’. The young man and his dog have been inseparable ever since. Shikari even sleeps outside of the door to the family shop where Jamir spends the night. “Shikari and I will go home to Myanmar, inshallah,” he says.

Jamir, 15

“If I’m in a crisis, maybe no one will come to help me – but Shikari will always come.”

Fifteen-year-old Jamir* reaches toward his dog Shirkari, outside of the small shop his family run in a refugee settlement in southern Bangladesh. “Shikari is the most important thing that came from Myanmar, because he is my best friend and my protector.” says Jamir. Jamir, whose family fled Myanmar 28 years ago, was born in the settlement and has never set foot in Myanmar. He first saw the dog last autumn, shortly after it arrived from Myanmar with a Rohingya refugee. When the animal approached him and sniffed his foot, Jamir threw a piece of food. After the dog sprang into the air to catch it, Jamir named him Shikari, which means ‘hunter’. The young man and his dog have been inseparable ever since. Shikari even sleeps outside of the door to the family shop where Jamir spends the night. “Shikari and I will go home to Myanmar, inshallah,” he says.

Kalima, 20

Kalima, who still struggles with the memories of the massacre, says nothing is important to her now after the unspeakable losses she suffered in Myanmar.

“I don’t know why Allah did not let me die,” the 20-year-old says through tears. She had been married just three months when attackers came to her village, burning houses and opening fire on the people. Surrounded by armed men, Kalima watched, terrified, as babies were thrown into the water and groups of children were set on fire. Kalima’s husband and little sister were shot. She was then brutally beaten and raped by multiple men, before being knocked unconscious. When she woke up, the house was on fire. She fled, walking for three days with her uncle and cousin into Bangladesh. Kalima was once a tailor and would very much like to sew again. When asked what her specialty garment is, she transforms from a weeping, stooped figure into a confident and composed young woman. “Anything you need!” she says, smiling.

Kalima, 20

Kalima, who still struggles with the memories of the massacre, says nothing is important to her now after the unspeakable losses she suffered in Myanmar.

“I don’t know why Allah did not let me die,” the 20-year-old says through tears. She had been married just three months when attackers came to her village, burning houses and opening fire on the people. Surrounded by armed men, Kalima watched, terrified, as babies were thrown into the water and groups of children were set on fire. Kalima’s husband and little sister were shot. She was then brutally beaten and raped by multiple men, before being knocked unconscious. When she woke up, the house was on fire. She fled, walking for three days with her uncle and cousin into Bangladesh. Kalima was once a tailor and would very much like to sew again. When asked what her specialty garment is, she transforms from a weeping, stooped figure into a confident and composed young woman. “Anything you need!” she says, smiling.

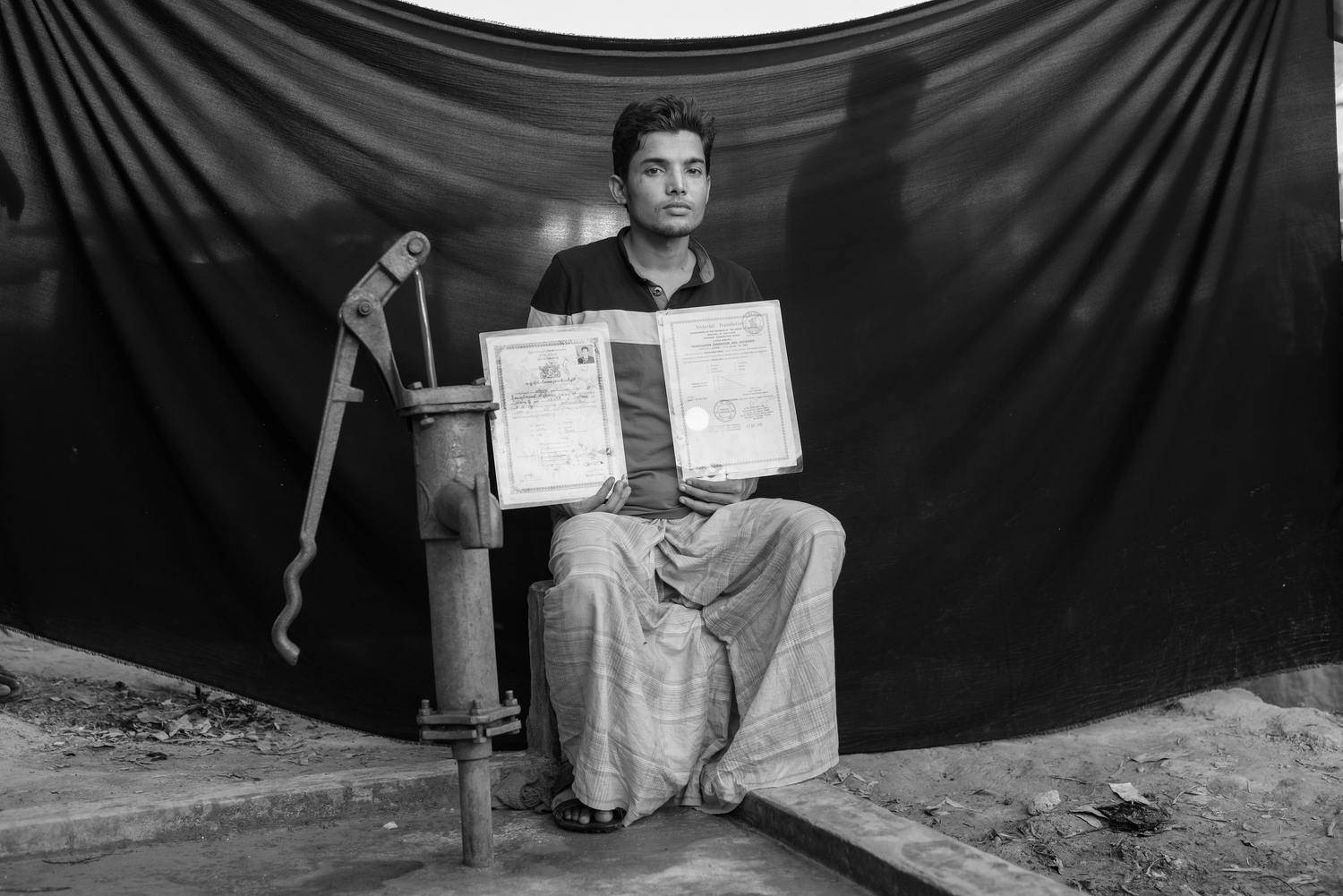

Mohammed, 26

The most important thing Mohammed brought with him to Bangladesh are his educational certificates, which are required for any formal job back home.

Mohammed, 26, was the only person from his village to study at university. The young man had almost secured a BA in English when Rohingya were banned from attending Myanmar’s Sittwe University. Returning to his village, he found work with the aid organization CARE and focused his energies on helping people. After a nearby village was attacked and Mohammed failed to save a 10-year-old boy who had been soaked in petrol and set alight, he stuffed his educational certificates, his laptop and a change of clothes into a bag and fled. Shortly afterwards, his village was set on fire, the women gang-raped and men killed. “Here, I don’t feel well,” he says. “In Myanmar, I had a big home, clean water and a good job. I want to go back – but I won’t go unless we are given citizenship.”

Mohammed, 26

The most important thing Mohammed brought with him to Bangladesh are his educational certificates, which are required for any formal job back home.

Mohammed, 26, was the only person from his village to study at university. The young man had almost secured a BA in English when Rohingya were banned from attending Myanmar’s Sittwe University. Returning to his village, he found work with the aid organization CARE and focused his energies on helping people. After a nearby village was attacked and Mohammed failed to save a 10-year-old boy who had been soaked in petrol and set alight, he stuffed his educational certificates, his laptop and a change of clothes into a bag and fled. Shortly afterwards, his village was set on fire, the women gang-raped and men killed. “Here, I don’t feel well,” he says. “In Myanmar, I had a big home, clean water and a good job. I want to go back – but I won’t go unless we are given citizenship.”

Noor, 50

The only thing Noor escaped with were the clothes he was wearing that day – a wrap skirt known as a lunghi.

In Myanmar, the government doesn’t let Rohingya train to become doctors. But Noor gained skills abroad and was determined to treat the illnesses that plagued his community at home, like fever and diarrhoea. “People saw me every day for treatment because I am honest and treated them with love,” he recalls. When the attacks on his village began, he treated countless survivors of rape and beatings. He was arrested repeatedly and often fined. In August 2017, as homes burned in a nearby village burned, he fled with his wife and their eight children. It took 15 days to reach the refugee settlement in Bangladesh. The only thing he brought was the wrap skirt he was wearing that day. “When I see it I miss my country, my house and my former life,” he says. “It is the lunghi I will wear when I return to Myanmar.”

Noor, 50

The only thing Noor escaped with were the clothes he was wearing that day – a wrap skirt known as a lunghi.

In Myanmar, the government doesn’t let Rohingya train to become doctors. But Noor gained skills abroad and was determined to treat the illnesses that plagued his community at home, like fever and diarrhoea. “People saw me every day for treatment because I am honest and treated them with love,” he recalls. When the attacks on his village began, he treated countless survivors of rape and beatings. He was arrested repeatedly and often fined. In August 2017, as homes burned in a nearby village burned, he fled with his wife and their eight children. It took 15 days to reach the refugee settlement in Bangladesh. The only thing he brought was the wrap skirt he was wearing that day. “When I see it I miss my country, my house and my former life,” he says. “It is the lunghi I will wear when I return to Myanmar.”

Shahina, 5

The most important thing five-year-old Shahina* would take from home if she had to flee is her blue cloth bag filled with beauty products.

The little girl says these items make her feel beautiful and that she loves to see the older pretty Rohingya girls making up their faces. When Shahina’s mother, Nosina, saw the latest influx of Rohingya people fleeing Myanmar she was grateful that her children were already safe in Bangladesh. She fled her village in Myanmar, seven years ago with her two small children. Shahina, the youngest, was born in Bangladesh. Shahina, who poses in front of the family’s shelter with her eight-year-old sister Rabiaa*, says that she would like to be a dance teacher when she grows up.

Shahina, 5

The most important thing five-year-old Shahina* would take from home if she had to flee is her blue cloth bag filled with beauty products.

The little girl says these items make her feel beautiful and that she loves to see the older pretty Rohingya girls making up their faces. When Shahina’s mother, Nosina, saw the latest influx of Rohingya people fleeing Myanmar she was grateful that her children were already safe in Bangladesh. She fled her village in Myanmar, seven years ago with her two small children. Shahina, the youngest, was born in Bangladesh. Shahina, who poses in front of the family’s shelter with her eight-year-old sister Rabiaa*, says that she would like to be a dance teacher when she grows up.

Hafaja, 60

There was just enough time to grab a solar panel and scream for her children, four sons and daughter before the attackers opened fire.

Hafaja, 60, was outside of her house when attackers came to her village, in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. “If I’d had even one minute to choose something else, I would have brought our money,” she says. “We had 500,000 kyat (about US$375) that was our family savings, but it is lost.” Hafaja watched her house burn from a nearby forest, across a field littered with the bodies of her neighbours who did not manage to flee in time. She then walked for three days with the panel in one hand and a walking stick in the other. “Solar is important because when night comes, the light allows me to pray and cook,” she says from Bangladesh. “When the light is on, I feel more safe. I lost my land, my money and my house, but it doesn’t matter. I still have my husband and my children. Others weren’t so lucky.”

Hafaja, 60

There was just enough time to grab a solar panel and scream for her children, four sons and daughter before the attackers opened fire.

Hafaja, 60, was outside of her house when attackers came to her village, in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. “If I’d had even one minute to choose something else, I would have brought our money,” she says. “We had 500,000 kyat (about US$375) that was our family savings, but it is lost.” Hafaja watched her house burn from a nearby forest, across a field littered with the bodies of her neighbours who did not manage to flee in time. She then walked for three days with the panel in one hand and a walking stick in the other. “Solar is important because when night comes, the light allows me to pray and cook,” she says from Bangladesh. “When the light is on, I feel more safe. I lost my land, my money and my house, but it doesn’t matter. I still have my husband and my children. Others weren’t so lucky.”

Mohammed, 44

The most important thing Mohammed brought with him are his land use documents from Myanmar.

Before he was forced to flee an attack on his home, Mohammed was chairman of his village and had a thriving 100 kani (132 acre) farm that included a large family house, two lakes, a rice paddy, vegetables and several cows, chickens and goats. Today, the 44-year-old lives in a refugee settlement in southern Bangladesh without enough food to feed his family. The most important thing Mohammed brought with him are his land use documents from Myanmar. As a Rohingya, these documents showed he was entitled to use the land. “We will return and rebuild and be productive again,” he says. “If I go back to Myanmar and have to prove where my land is, these documents will help.” Mohammed says that he will only return when the Rohingya are counted as one of Myanmar’s official ethnic groups and given citizenship.

Mohammed, 44

The most important thing Mohammed brought with him are his land use documents from Myanmar.

Before he was forced to flee an attack on his home, Mohammed was chairman of his village and had a thriving 100 kani (132 acre) farm that included a large family house, two lakes, a rice paddy, vegetables and several cows, chickens and goats. Today, the 44-year-old lives in a refugee settlement in southern Bangladesh without enough food to feed his family. The most important thing Mohammed brought with him are his land use documents from Myanmar. As a Rohingya, these documents showed he was entitled to use the land. “We will return and rebuild and be productive again,” he says. “If I go back to Myanmar and have to prove where my land is, these documents will help.” Mohammed says that he will only return when the Rohingya are counted as one of Myanmar’s official ethnic groups and given citizenship.

Yacoub, 15

The chain around 15-year-old Yacoub’s* neck is the only thing he has left to remind him of his father.

The last time they spoke, it was early in the morning and the man was heading out to gather firewood. That same day, there was a brutal attack on Yacoub’s village. When he saw his home burning, Yacoub, who lost his mother in childbirth when he was eight, took his two little sisters by the hand and ran barefoot into the jungle. They stayed hidden for 15 days, living on biscuits and tea brought from their uncle’s shop and later by picking rose apples. Yacoub bought his necklace at a market in Myanmar five months ago with money his father had given him as a gift. The boy now lives alone in a tent, with just his new puppy Sitara, a sleeping mat and a blanket. His aunt, uncle and sisters live next door. Nobody knows what became of his father.

Yacoub, 15

The chain around 15-year-old Yacoub’s* neck is the only thing he has left to remind him of his father.

The last time they spoke, it was early in the morning and the man was heading out to gather firewood. That same day, there was a brutal attack on Yacoub’s village. When he saw his home burning, Yacoub, who lost his mother in childbirth when he was eight, took his two little sisters by the hand and ran barefoot into the jungle. They stayed hidden for 15 days, living on biscuits and tea brought from their uncle’s shop and later by picking rose apples. Yacoub bought his necklace at a market in Myanmar five months ago with money his father had given him as a gift. The boy now lives alone in a tent, with just his new puppy Sitara, a sleeping mat and a blanket. His aunt, uncle and sisters live next door. Nobody knows what became of his father.

To support our work with individuals fleeing armed conflict and violence, please donate now.

More on the Rohingya refugee emergency:

At a Glance | Data portal | Emergency page | Supplementary appeal