Taking a bank card to a cash machine in Beirut, Syrian widow Manar Al Sayer taps in a PIN and withdraws a few Lebanese pounds.

Cash in hand, she can now prioritize her monthly spending for herself and her three children, Aseel, six, Abdullah, nine, and Osaima 12.

“I allocate this cash assistance so that my children can attend the morning shift at school,” she explains.

“I use [it] to pay for my children’s school transport and I am very happy that I am now able to pay for something,” she adds.

Uprooted from her family home in Homs by shelling in 2012, Manar sought refuge in neighbouring Lebanon the following year. After her husband was killed in a traffic accident, she is now head of the family.

"What we buy is no longer imposed on us."

Once she has taken care of her children’s schooling, Manar can budget for the remainder of the month.

“I promised my children to buy them slippers with part of this month’s cash assistance. So I am going to do that because I have the money,” she adds.

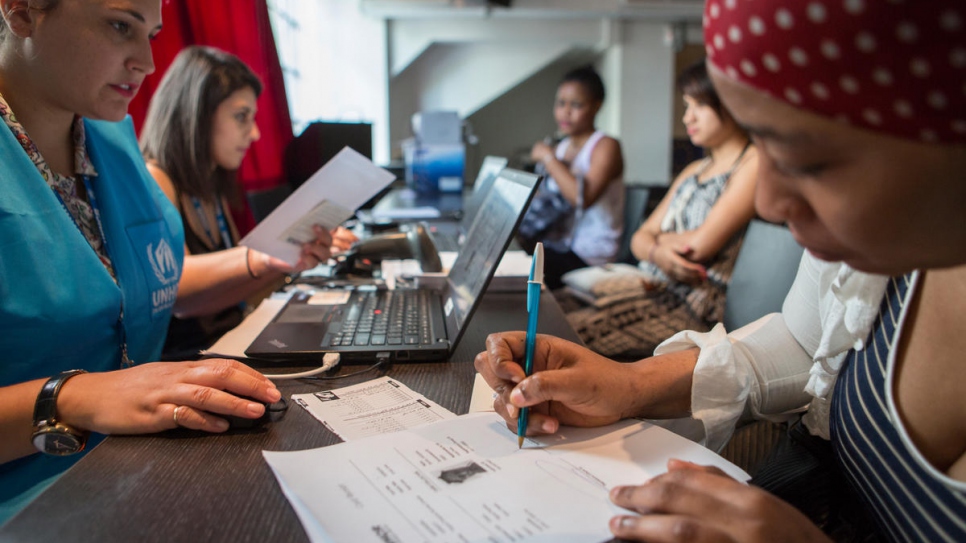

The 29-year-old is among millions of refugees and others of concern in scores of countries worldwide who have been able to take greater control of their lives since UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, began expanding cash-based assistance in 2016.

The programme aims to help refugees, asylum-seekers, returnees, internally displaced and stateless people meet their needs in dignity, are protected and can become more resilient. In the past two years it helped 10.5 million people in need in 94 countries, and UNHCR now provides more cash than in-kind aid.

Most of the money is disbursed without restrictions, meaning that refugees themselves can choose how they spend it. This benefits the local economy as refugees buy essential goods in local stores and pay for local services.

“Before we were restricted to spending the cash assistance in supermarkets. But when they made it available in cash, they gave us the freedom of choice. What we buy is no longer imposed on us,’’ says Manar.

While she prioritizes spending on her children’s schooling, other people of concern from Greece to Niger and Somalia are using cash assistance to pay their rent, buy medicines, pay off debts or even start businesses. Flexible and innovatory, the initiative is even helping displaced people living in some of the more remote places where UNHCR works, such as camps in Niger.

At the West African country’s Tabareybarey refugee camp, UNHCR distributed 2,500 mobile phones to refugees. Using safe and secure electronic payments – so-called “Mobile Money” – it is assisting 10,000 men, women and children who fled insecurity in Mali.

An SMS message notifies beneficiaries that they have received their assistance. They can then withdraw the cash at the phone shop – a red booth in the camp – or pay for goods directly with their phones in the local stores.

“We’ve seen that providing cash instead of goods is one of the best ways to address refugees’ basic needs here in Niger,” says Robert Heyn, UNHCR’s associate programme officer for cash-based interventions in the country.

“It’s more cost effective, it gives refugees dignity of choice and it also has a very positive impact on the local economy. So it benefits the refugees and the host economy at the same time.”

"It benefits the refugees and the host economy at the same time.”

Those in receipt of Mobile Money no longer need to carry cash in their wallet with them, but can access their money “whenever they need it, whenever it’s necessary, and they can also leave money on their mobile money accounts,” says Heyn.

The flexibility and security is welcomed by refugees, among them Zeinabu Warekoufaf from Mali. “When you have your money in your mobile phone, nobody knows what you have and if somebody takes it from you, he won’t know how much you have,” she says.

Visiting a shop at the settlement, Zeinabu uses cash to buy sugar, tea and couscous, as well as skeins of brightly coloured wool from which she make cushions to sell. Many of the shopkeepers have increased their revenue since the refugees started getting money and are happy with the arrangement.

UNHCR hopes that the freedom and security that Mobile Money provides will allow refugees like Zeinabu to leave the camps and integrate into the local community, where they can live in a more independent and sustainable way.

In 2016 and 2017, the first two years that it ramped up cash-based assistance, UNHCR distributed a total of US$1.2 billion, in partnership with governments, UN agencies, NGOs and the private sector.

The largest operations to date are in Lebanon, Afghanistan, Jordan, Somalia, Ukraine, Sudan, Iraq, Egypt, Syria and Turkey, although operations have since rolled out in other countries including Bangladesh, where it is helping some 45,000 Rohingya refugees in informal settlements.

“The first thing I’ll do is pay off our debts of around 200 taka (US$2.50), and then we’ll use this money to buy food”, said Samuda, a lone mother with a 15-year-old daughter, at the launch of the pilot project in southeast Bangladesh in April.

The cash-based interventions cover the whole arc of displacement, from helping people uprooted within and beyond the borders of their own countries, to assisting those who opt to return home when conditions are safe enough – among them thousands of Somalis.

Nearly three decades of civil war in the Horn of Africa country uprooted more than two million people to neighbouring countries. With security at home improving, 80,000 refugees have so far returned voluntarily, for whom cash is proving vital as they restart their lives in their still fragile homeland.

Through its partner Amal Bank – which offers a range of financial services from money transfers to microfinance in cities and remote areas of Somalia – UNHCR is disbursing a bundle of grants to returnees including a one-time cash allowance, monthly support, allowances for each child and shelter grants. In an important step toward full reintegration, returnees also have their own bank accounts making it possible to receive and save money.

Among beneficiaries is mother of five Aisha, 55, who spent 25 years as a refugee in Dadaab, Kenya. On returning to Somalia in early 2017, she used a reinstallation grant of US$200 to set up a small store in Kismayo, selling everything from bananas and watermelons to pens.

Returnees also have their own bank accounts making it possible to receive and save money.

“It allows me to cater to most of my family’s needs,” she says of the shop, stocked with items bought from local wholesalers in the country, now getting back on its feet after decades of war and instability.

Others are using their cash grants and assistance to buy land and livestock, or start a business, like 47-year-old Mohamed Noor Omar, who faced an uncertain future in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya after fleeing civil war in his native Somalia in the early 1990s.

With the allure of grants totalling US$1,600, he returned to the Somali capital, Mogadishu last year, where he used some of the money to buy a fishing boat. He also partnered with a local man who had an engine to run it.

Out on the water by 6 a.m., he makes US$7 to US$10 a day depending on the catch, and is now looking to improve his business like any other entrepreneur.

“That income is enough to meet my basic requirements,” says Mohamed, who wants to buy better nets to catch more fish, and an outboard motor that can take him further offshore. “That way I can improve my living conditions.”

Reporting by Rima Cherri and Houssam Hariri in Lebanon, Caroline Gluck in Bangladesh, Robert Heyn in Niger, and Njoki Mwangi and Urayayi Mutsindikwa in Somalia.