Project Elpis offers a ray of hope in refugee camps

A small solar device, developed by Edinburgh students, helps refugees in Greece overcome communication challenges.

University of Edinburgh students Samuel Kellerhals (left), 21, and Alexandros Angelopoulos (right), 20, have developed and installed solar-powered mobile phone chargers in refugee camps. © UNHCR/Claire Thomas

Edinburgh // It was on the Greek island of Samos in mid-2015 that Alexandros Angelopoulos first saw the need to help refugees communicate.

The young, Scotland-based student was volunteering with a marine-focused non-governmental organisation in the Eastern Aegean when Samos suddenly witnessed an influx of unexpected arrivals. In 2015, over 800,000 refugees and migrants landed in Greece from Turkey via the Aegean.

“We didn’t really know what was happening,” Angelopoulos, 20, told UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. “This was something else – multiple boats arriving at night. It was pretty chaotic.”

Islanders tried to help the newly-arrived refugees as best they could, he said, by distributing food, water and blankets. But there were also tensions. “I was approached by a group of teenagers asking me if they could use my phone,” Angelopoulos said. “They had tried to go to a local café to charge but had been turned away.”

"I placed myself in their shoes." The idea of Project Elpis came when Alexandros volunteered on the Greek island of Samos in mid-2015. © UNHCR/Claire Thomas

That set the young scientist’s mind whirring on a plan that would ultimately spawn Project Elpis, a small solar-powered battery charger for a dozen mobile phones which can also store information, including education material.

The prototype has been developed by Angelopoulos and Samuel Kellerhals, 21, both undergraduates at Edinburgh University’s Environmental Sciences Department. The two now hope to advance from pilot versions already in use in Greek refugee camps, to a fully-fledged version that is adaptable, robust and deployable anywhere at short notice.

"After going through all these dangers and obstacles to get to a new country, why then also face such a basic problem as how to charge a phone, or where to charge it"

The idea came from a simple question: what is the one thing refugees take with them when forced to flee? The answer – a mobile phone – suggested itself quickly. But it was also, they both discovered, controversial. “There’s a lot of stigma around it,” Kellerhals said.

They started pitching the charger idea, first to friends and acquaintances and then potential investors. “We started getting questions about why refugees have mobile phones,” Angelopoulos added. They are supposed to be destitute, he said, and a “mobile phone is seen as a luxury item.”

The Raspberry Pi provides refugees with free access to digital content including a library of books, legal information and educational resources. © UNHCR/Claire Thomas

From his experience with refugees on Samos, Angelopoulos could see that a mobile phone was an important lifeline. Not just as a means of communication, but also a way of accessing information, staying informed about complex immigration procedures, finding new transit routes and staying in touch with Syria and family members.

In fact, refugees have been adept at keeping mobile costs down, by buying cheap or second-hand devices, sharing access to internet or SIM cards and using free messaging services like Viber and WhatsApp.

“I placed myself in their shoes and thought, after going through all these dangers and obstacles to get to a new country, why then also face such a basic problem as how to charge a phone, or where to charge it,” Angelopoulos said.

The two set about creating a charger that would not need plug-in power and could be deployed “completely off-grid.” It had to be small, cheap and solar-powered.

They began in earnest in October 2015; the first prototype was ready in December, a simple solar charger with 12 plugs. Commercially available solar chargers typically take several hours to charge one phone; Elpis can charge a dozen in just over an hour.

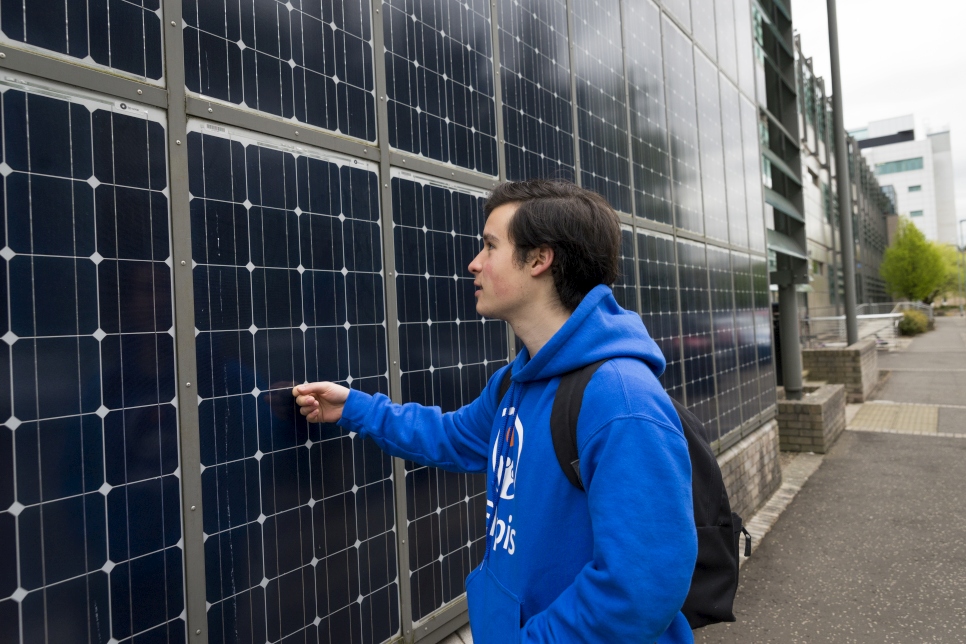

Samuel Kellerhals, 21, stands next to a wall of solar panels at the King's Buildings campus of the University of Edinburgh. © UNHCR/Claire Thomas

Their project soon gathered momentum – after funding was secured from Edinburgh University’s Scholarships and Student Funding Department and via crowd-funding efforts, with the support of the university Chaplaincy. It was first deployed in mid-2016 when Angelopoulos and Kellerhals went to Elliniko Camp in Athens and Lesvos.

“That whole trip was crazy,” Kellerhals said. “It was heart-breaking. There were loads of children, rubbish everywhere – it opened my eyes to how bad it really is.”

The trip also provided ideas for development.

“Most residents don’t have access to the internet unless they pay for it,” Angelopoulos said. And they were starved of information, especially in Arabic. “Some of them were asking for WiFi and information, and that’s what triggered the second part of the project.”

Project Elpis – version 2.0, as it were – added a Raspberry Pi hard drive, a tiny storage device from which users can download data. The Pi is attached to the solar panels making a unit that functions both as a charger and a store of information. The data stored can be customised. Currently, the information includes a library with sections on family health, personal development and maths and science books in Arabic and English.

Alexandros Angelapoulos holds a Raspberry Pi computer inside a lab at the University of Edinburgh. © UNHCR/Claire Thomas

The information can be accessed remotely through mobile phones with up to 60 connections at a time.

So far, 12 units have been deployed in Greece, seven of the old version and five with the drive. But the two undergraduates are still looking to innovate and find commercial applications. Economies of scale are at play. Each unit costs around £800; the more units are made, the cheaper they become.

“It was heart-breaking...it opened my eyes to how bad it really is.”

It’s been a long journey for Angelopoulos and Kellerhals, who are due to graduate this summer. But they remain as enthusiastic about Elpis – named after the Greek goddess of hope – as at the outset. They hope to find commercial uses (and new backers) for the device to help fund further development.

“We want to help as many people as possible, but we want to also make it work in a financially-sustainable way,” Kellerhals said. “There’s lots of potential.”

But their priority remains helping refugees at no cost. The whole experience, Angelopolous said, has been “humbling.”

“The aim,” he added, “is to give something back.

This story is part of a series exploring the ways people across the UK are showing refugees and asylum-seekers a #GreatBritishWelcome.