Greek exhibition gives Slovaks a sense of the refugee experience

Acclaimed Greek photo exhibition goes on tour to Slovakia, a country with less experience of welcoming refugees.

© UNHCR/Zsolt Balla

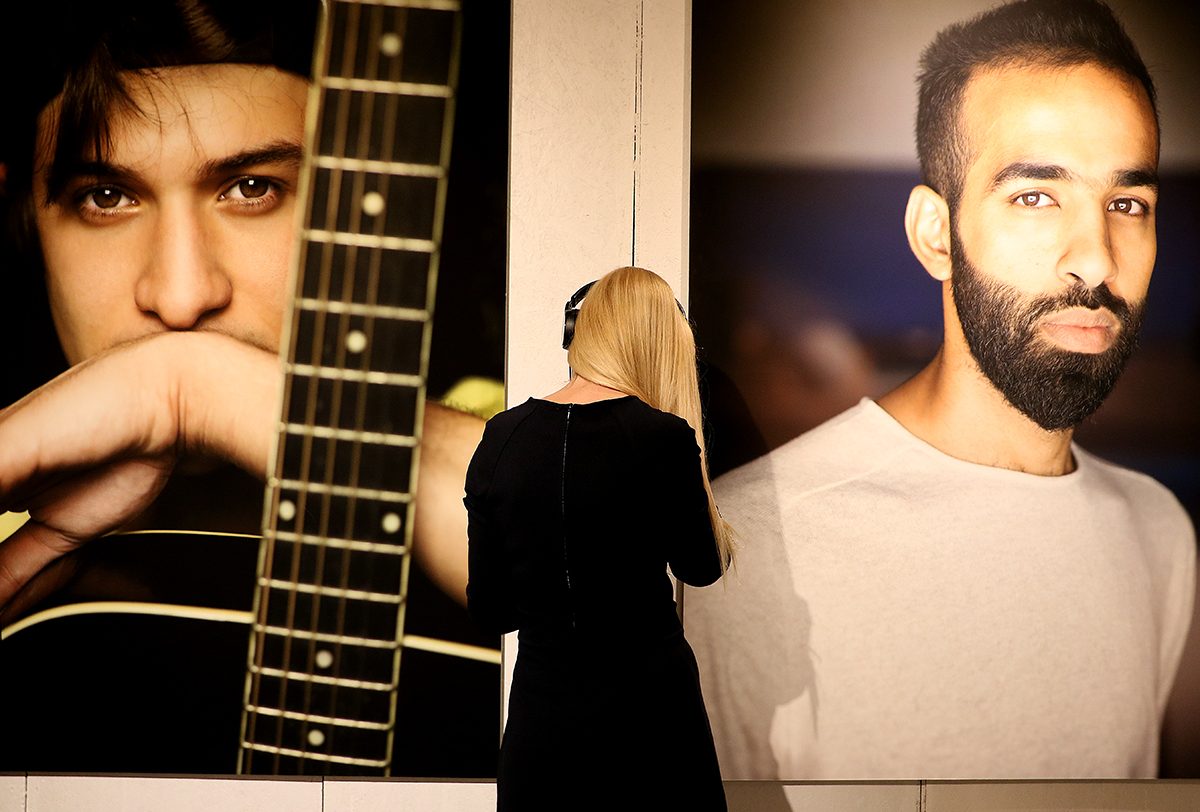

“It touches me,” says Slovak economics lecturer Marcela Rabat, walking round an exhibition of photographs of refugees who are trying to make new lives in Greece. The acclaimed, interactive Greek exhibition, Face Forward into my Home, is on display for the first time outside Greece in Slovakia, a country with less experience of welcoming refugees.

When you start listening to the stories, you have to listen to the end.

The Slovak ambassador to Greece, Iveta Hricová, was instrumental in bringing the exhibition to the eastern city of Košice. At the opening in January in the Tabacka Kulturfabrik cultural centre, she thanked the city for its cooperation and urged visitors to look at the refugee portraits “with empathy”.

Also speaking at the opening, UNHCR’s representative for Central Europe, Montserrat Feixas Vihe, said that although the refugee crisis had dropped from newspaper headlines, the plight of refugees remained acute and countries like Slovakia could play an important role in helping them to rebuild their lives.

Face Forward into my Home, which has already been seen and admired in Athens, Heraklion and Thessaloniki, was a joint project of the Greek National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) and UNHCR in Greece, funded by the European Commission. As a starting point for telling their stories, refugees were encouraged to look at art works in the museum. Greek photographer Ioannis Vastardis then followed them in their daily lives, taking pictures that reflected their dreams.

Beside the photos on the walls are sets of earphones so that visitors can listen to the recorded stories of the featured refugees. “We think the combination of strong images and strong narration will interest visitors,” says Marina Tsekou, educational curator at EMST. “When you start listening to the stories, you have to listen to the end.”

Carlos from Syria, for example, is inspired to start opening up about his own life by an art installation of coloured sails, facing in different directions. “It brought to mind what’s going on in my country, with the various factions and their differences,” he says. “But just the opposite happens when we meet at the museum. We’re all different, and think differently, but we realize we respect each other’s opinions.”

Holding glasses of wine and canapés, the invited Slovak guests mill around the exhibition.

“I am here out of personal and civic interest,” says Iveta Orbanova, whose NGO, the Astra Association for Innovation and Development, is trying to improve services for migrants through an initiative called Mamidi (Managing Migration and Diversity). “In the past, Slovakia has tended to be a country from which people migrated, so we don’t have much history or experience of migrants coming to our country.”

The faces and voices of the exhibition speak volumes about the refugee experience.

Ghassan from Syria, who hopes to become a shepherd in Greece, sits proudly for his portrait like the subject of an old Dutch master painting. Patricia from Cameroon describes her new life as a “transition to light after a difficult phase, sunk in the dark”.

Maya speaks openly about her struggle as a transgender person in Tunisia. “They say people who have been wounded in life become good people, and I believe it,” she says.

Photographer Ioannis Vastardis says his past work was often “enigmatic”, allowing room for subjective interpretation, but with the refugees, he has taken a realist approach.

“If we really believe we come from ancient Greeks, we would better remember that ‘asylum’ was originally a Greek word.”

He points to the picture of Bibiche from Congo. His inclination had been to highlight the contrast between her poor living conditions and the elegant way she dresses. But she wanted to be portrayed with a touch a luxury, so he photographed her in a cafe, with a cup of hot chocolate.

Ioannis spent weeks with the refugees to get each portrait absolutely right. He passionately believes in welcoming newcomers, with the culture and skills that they can bring.

“If we really believe we come from ancient Greeks,” he says, “we would do better not only to look at the Parthenon and all the old marbles but to remember that ‘asylum’ was originally a Greek word.”

A knot of guests stands by the picture of the youngest subject of the exhibition, 15-year-old John from Zimbabwe. At school, he read the Bible and Shakespeare and it turns out he is something of a poet himself. John, who looks dreamy in his portrait, has written a sonnet for the girlfriend from whom he is separated…

“Leandra

I am out for greener pastures

But do not put our love past us…”

The portrait seems to make a strong impression on Lubomir Sobek, a teacher of history and Russian at a high school in Košice.

“I try to explain about human rights to my pupils and they mostly respond positively,” he says. “This is a beautiful exhibition and I will definitely bring my students to see it.”