'I would have paid to do the work I was doing'

UNHCR has nearly 11,000 staff, most of whom are based in the field. Meet Roberto Mignone, the UN Refugee Agency's representative to Libya.

A refugee boy hugs UNHCR Libya Representative Roberto Mignone shortly after landing at Pratica di Mare Air Base, near Rome, on an evacuation flight from Libya.

© UNHCR/Alessandro Penso

Name: Roberto Mignone, 53, from Italy

Job title: UNHCR’s representative to Libya, based in neighbouring Tunisia.

Years at UNHCR: Almost 25, working in Mozambique, Guatemala, Colombia, Sweden, Australia, India and Costa Rica, then at headquarters in Geneva, as part of a team responding to emergencies worldwide.

Why did you become an aid worker?

I was backpacking through Asia, and I met Karen refugee children from Myanmar in a village in northern Thailand. I was giving them sweets and I was thinking ‘I hope, one day, I can come back with something better.’ That’s when I knew I wanted to work in this field.

The Karen were the first displaced indigenous people I met. But since joining UNHCR in 1993, I have worked with other indigenous people in Guatemala, Panama, Colombia, Costa Rica and the Philippines.

Working with them has become my priority and favourite area of work, because they are particularly vulnerable, and they are disproportionately affected by conflict. You have no doubt that they need protection.

What is the most rewarding/challenging thing about your job?

Being the representative in Libya is the most challenging job I’ve ever had. Our access to Libya is very, very limited. Because of security restrictions we can only send one person at a time from our base in Tunis to get into Libya. Then there is all the paraphernalia to move around. You need two armed vehicles, you need two armed close protection from diplomatic police, which is very paralyzing. So this is one huge challenge which implies remote management of our national team there.

There is more than one government. The one we are working with is in Tripoli, then other authorities around the country. We don’t have a memorandum of understanding, but our presence is tolerated. If I could change one thing, it would be being able to work from there.

More than six years of violent upheaval in Libya began with the uprising that removed ruler Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. We work with half a million people displaced within the country by conflict. These includes 200,000 displaced and 300,000 who were displaced but have recently returned, but are still in a fragile situation.

Then we work with refugees in the mixed migration movement, and there, also it is very complicated, because the authorities don’t recognize these people are refugees, and they don’t recognize our role. So now we have decided to evacuate thousands of refugees from Libya, because the situation is too dangerous for them.

While it is a challenge, we are making progress. So far this year we have had 950 people released from these horrible detention centres. Among them was an eight year old boy. I wrote a letter recently for another 2,280 who will be released, so to have these people taken out of detention will be pure protection work at its best.

Among the cases that stand out is that of some 30 women who were enslaved by extremists in Sirte. When the city was liberated, they were detained by Libyan authorities on the basis that they were the partners of extremists. So we had them released, then we had them resettled to a safe country.

What was the best day that you had at work?

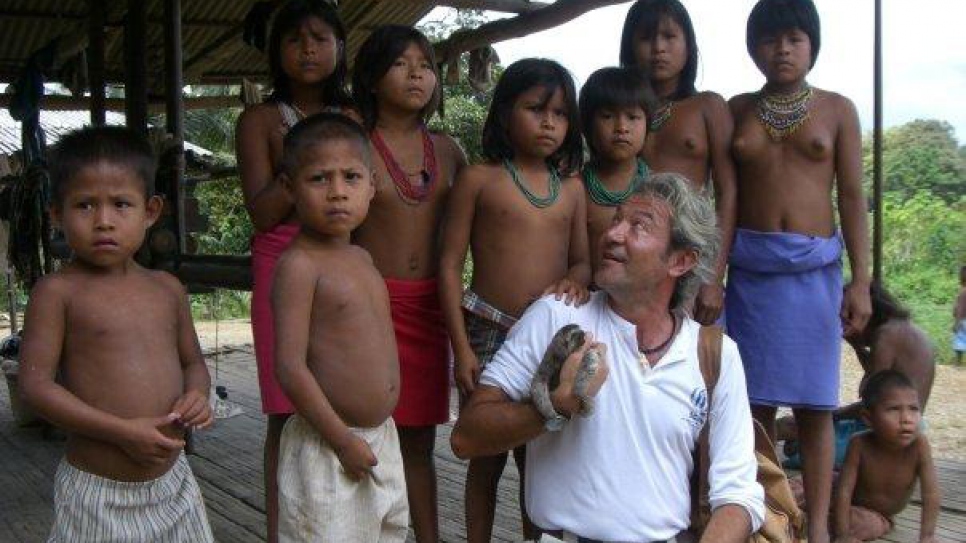

When I was in Colombia I carried out 250 missions to the deep field by horse, on foot, by small boat, going to communities in the remote jungle.

One time I remember we went to the Chocó region – on the Pacific coast bordering Panama. We had to take a boat for two days, across the ocean and then up a river, to where the Emberá indigenous people were confined by drug traffickers.

When we reached the village, everyone ran away, because, at the time, the only people who visited them meant them harm. So we spent a few days there and, little by little, they began to trust us. We explained ‘we’re here to protect you, we are not the bad guys,’ so they understood that.

I have a picture taken in the village. I am sitting and a little girl is standing behind me, and she put a hand on my shoulder. It meant that even the children understood that we were there to protect them, not to harm them. That was my best day at work.

I like working in the deep field best of all. I used to think when I was in Colombia, Guatemala and Mozambique, ‘are they paying me to do this?’ If they had told me, ‘no, we are not going to pay you anything, you have to pay,’ I would have paid to do the work I was doing.

What was your worst day at work?

My worst day was in Guatemala in 1995. It was during the civil war and I was working to protect Mayan refugees who had returned from Mexico to take part in the peace process.

Most of those who died in the conflict – which lasted from 1960 to 1996 – were Maya killed by the military. And we were like physical human shields between the army and the indigenous returnees. They used to alert us when soldiers entered their villages, because they were afraid of them.

On this particular day, we got a call from this community who told us that the army had them surrounded. So, I drove like crazy over unpaved roads, and all the time we could hear what was happening on the radio. The soldiers were killing people.

Just as we were arriving, we ran into the patrol as it was leaving. They had just killed 11 people, including a child. It was like they were in a trance, they raised their guns and they could have shot us very easily. Then we arrived at the village, and it was like Dante’s Inferno. There were people crying, it was full of blood and bodies.

Normally we have prevented these situations, by being there physically, in the middle. But that time, we came too late. But it showed us that what we did in other villages worked. Otherwise there could have been more situations like this.

The UN Refugee Agency works in 130 countries helping men, women and children driven from their homes by wars and persecution. Our headquarters are in Geneva, but 87 per cent of our staff are based in the field, helping refugees. This profile is one of a series highlighting our staff and their work.