Statelessness around the world

At least 10 million people in the world today are stateless. They are told that they don’t belong anywhere. They are denied a nationality. And without one, they are denied their basic rights.

While most of Europe’s Roma possess a nationality, the Zahirovic family remain stateless. They live in a cramped and flimsy room, with no running water, electricity or sanitation facilities in Croatia’s Vrtni Put. The family’s only source of income is from collecting scrap metal. UNHCR / Nevenka Lukin

Malak (4) is a Faili Kurd whose family fled from Iraq to Iran in 1980 after Saddam Hussein stripped the entire Faili Kurd community of their Iraqi citizenship, leaving them stateless. Since 2003, after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, reforms have been implemented to allow Faili Kurds to reacquire their Iraqi nationality. UNHCR / Greg Constantine

Despite a 2008 Constitutional Court judgment confirming the Bangladeshi citizenship of Urdu speakers, a long history of statelessness and exclusion means that a madrassa (Islamic school) is the only place that many of the children in the Geneva Camp of Mohammadpur in Dhaka can access primary school education. UNHCR / Syed Latif Hossain

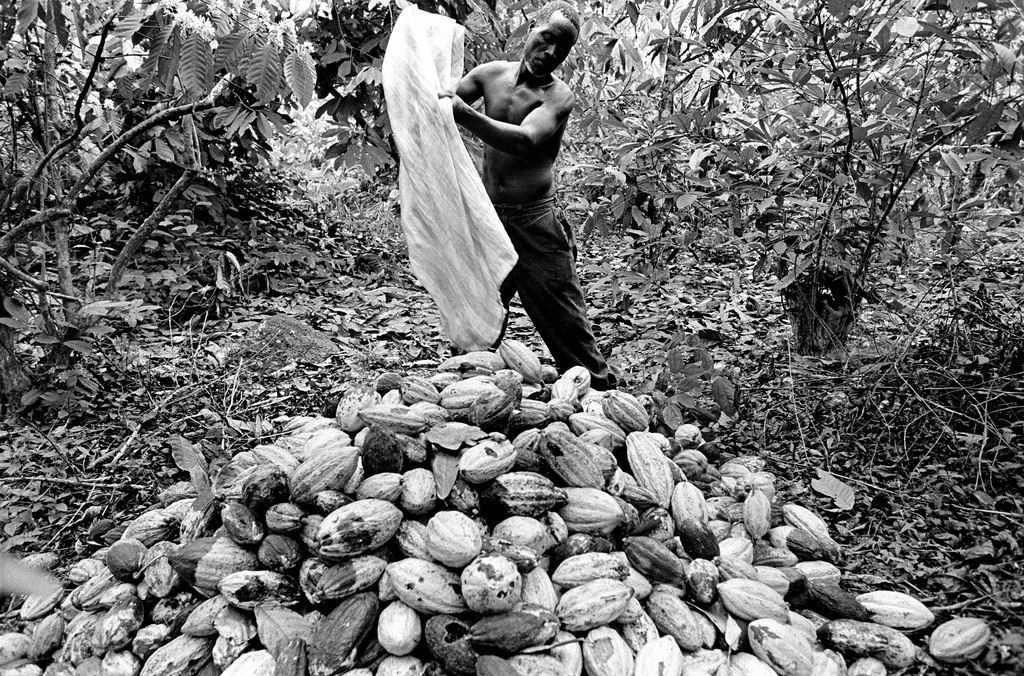

A stateless man collects cocoa on a small plantation near Bouafle. Côte d’Ivoire. Most of the 700,000 people estimated to be stateless in the West African country are comprised of descendants of foreign immigrants who came to work on the country’s cocoa plantations many decades ago. Legislative reforms in 2013 mean that many finally have the chance to acquire citizenship. UNHCR/ Greg Constantine

An ethnic Korean who moved to Ukraine in 1993 and lived with a local woman for more than a decade without being able to officially register their union. UNHCR / Greg Constantine

A Galjeel child plays in an abandoned school in northern Kenya. The Galjeel, numbering 3,500 to 4,000 people, are a sub-clan of Somali descent and have lived in Kenya since the late 1930s. Most stateless Galjeel children in northern Kenya do not go to school. But those who do must walk several miles and are often harassed by other ethnic groups. UNHCR / Greg Constantine

Valentina, seen with her grandchildren in Riga, Latvia, is the only stateless member of her family. She and her husband moved from Belarus to Latvia in 1983, when both countries were part of the Soviet Union. They had four children, all of whom are now citizens of Latvia. Valentina voted for independence in 1991, but has not taken the Latvian language test that will enable her to get nationality. She is scared that she will not pass. “I’m a citizen of nowhere. When I travel with the family, the immigration officers stare at my non-citizen passport as if it was a museum piece,” says Valentina. UNHCR / Lionel Charrier

Children in Telipok, Sabah, Malaysia. Many children of migrants are unable to establish a nationality. Some are completely undocumented and do not have access to education. UNHCR / Greg Constantine

This stateless mother came to Kyrgyzstan from Tajikistan. Her children are also stateless as a result. Without papers proving her nationality, she cannot receive badly needed social assistance. UNHCR / Alimzhan Zhorobaev

Nusret, aged 49, is a statelessness person living in Montenegro: “I feel like I’m quarantined,” he says. “I can move around town where people know me, but I can’t go anywhere else without documents. I can’t visit my sick mother in Kosovo.“ UNHCR / Nevenka Lukin

Seventeen-year-old Mohamed sits in front of his house in the village of Saria, Côte d’Ivoire. He was born in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, to Burkinabè parents. They died when he was young and Mohamed came to Côte d’Ivoire with his uncle. His birth was never registered in Burkina Faso and he has no documentation to prove his parents’ Burkinabè nationality. Mohamed has resigned himself to never leaving Saria. “When I tried to travel to neighbouring towns to sell my harvest, policemen or military stopped me and forced me to pay 10,000 West African francs (US$20), which is half of my annual wages,” he reveals. UNHCR / Helene Caux