TO DISCOVER THE SPECIAL PAGER ON THE ROHINGYA CRISIS AND THE OTHER LANGUAGE VERSIONS PLEASE CLICK HERE.

Discrimination, exclusion and persecution most commonly describe the existence of stateless minorities.

More than 75% of the world’s known stateless populations belong to minority groups.

“Imagine being told you don’t belong because of the language you speak, the faith you follow, the customs you practice or the colour of your skin. This is the stark reality for many of the world’s stateless. Discrimination, which can be the root cause of their lack of nationality, also pervades their everyday lives – often with crippling effects. If we want to end statelessness, we must address this discrimination. We must insist on equal nationality rights for all.”

Filippo Grandi

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES

KEY FINDINGS

Statelessness can exacerbate the exclusion that minorities already face, further limiting their access to education, health care, legal employment, freedom of movement, development opportunities and the right to vote. It creates a chasm between affected groups and the wider community, deepening their sense of being outsiders: of never belonging.

In May and June 2017, UNHCR spoke with more than 120 individuals who belong to stateless or formerly stateless minority groups in three countries: the Karana of Madagascar, Roma and other ethnic minorities in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and the Pemba and Makonde of Kenya. These are the key findings of UNHCR’s consultations:

Discrimination

Discrimination and exclusion of ethnic, religious or linguistic minority groups often lies at the heart of their statelessness. At the same time, their statelessness can lead to further discrimination, both in in practice and in law: at least 20 countries maintain nationality laws in which nationality can be denied or deprived in a discriminatory manner.

© UNHCR/Roger Arnold

“A certain political leader was asked how he viewed the Makonde and he shamelessly responded to the crowd that he saw us as cannibals,”

remembers Thomas Nguli, 60, from the Makonde community in Kenya.

Lack of documentation

Discrimination against the stateless minorities consulted manifests itself most clearly in their attempts to access documentation needed to prove their nationality or their entitlement to nationality, such as a national ID card or a birth certificate. Lack of such documentary proof can result in a vicious circle, where authorities refuse to recognize an otherwise valid claim to nationality.

© UNHCR/Roger Arnold

“The authorities told me that I had to go to Kosovo to get a certificate that I was not a citizen of Kosovo. But how could I travel there without documents?

asks Sutki Sokolovski, a 28-year-old ethnic Albanian man. His mother, who abandoned him as a child was from Kosovo (S/RES/1244(1999)), but he was born in The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and has lived there his entire life.

Poverty

Because of their statelessness and lack of documentation, the groups consulted are typically excluded from accessing legal or sustainable employment, or obtaining the kinds of loans or licenses that would allow them to make a decent living. This marginalization can make it difficult for stateless minorities to escape an ongoing cycle of poverty.

© UNHCR/Roger Arnold

“The biggest problem is the poverty caused by my statelessness. A stateless person cannot own property. I feel belittled and disgraced by the situation that I am in,”

notes Shaame Hamisi, 55 from the stateless Pemba community in Kenya

Fear

All the groups consulted spoke of their fear for their physical safety and security on account of being stateless. Being criminalized for a situation that they are unable to remedy has left psychological scars and a sense of vulnerability among many.

© UNHCR/Roger Arnold

“They [police] know what we do, where we go. They ask for our IDs, when we say we don’t have any, we are arrested and beaten,”

says Ajnur Demir, 26, from the Roma community from the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

SOLUTIONS

“I felt like I was a slave. Now I feel like I have been born again,” says 51-year-old Amina Kassim, a formerly stateless member of the Makonde community in Kenya.

© UNHCR/Roger Arnold

Ensuring equal access to nationality rights for minority groups is one of the key goals of UNHCR’s #IBelong Campaign to End Statelessness by 2024.

To achieve this, UNHCR urges all States to take the following steps, in line with Actions 1, 2, 4, 7 and 8 of UNHCR’s Global Action Plan to End Statelessness:

- Facilitate the naturalization or confirmation of nationality for stateless minority groups resident on the territory provided that they were born or have resided there before a particular date, or have parents or grandparents who meet these criteria.

- Allow children to gain the nationality of the country in which they were born if they would otherwise be stateless.

- Eliminate laws and practices that deny or deprive persons of nationality on the basis of discriminatory grounds such as race, ethnicity, religion, or linguistic minority status.

- Ensure universal birth registration to prevent statelessness.

- Eliminate procedural and practical obstacles to the issuance of nationality documentation to those entitled to it under law.

The Karana of Madagascar

Sougrabay Ibrahim, who is 84 years old and still stateless has never attended school. © UNHCR/Roger Arnold

The Karana minority in Madagascar has been present on the island nation for more than a century. They trace their origins to the western provinces of pre-partition India. The most significant wave of migration from India to Madagascar took place in the latter half of the nineteenth century, when seafaring trade on the Indian Ocean became more competitive.

There is no reliable data concerning the exact number of Karana on Madagascar; while it’s popularly believed that this Indian-origin minority numbers some 20,000, the actual figure might be significantly higher.

“We are here. We are your neighbors. When it rains it rains for all of us.”

The vast majority of these people were born in Madagascar and spent their entire lives on the island. Most live in urban areas, including the capital, Antananarivo, and the city of Mahajanga on the northwest coast. The fact that the Karana are predominantly Muslim has contributed to a perception of them as outsiders.

Madagascar’s nationality law follows the principle of jus sanguinis, granting citizenship at birth to children who have at least one parent who possesses Malagasy nationality. The Karana were generally not given citizenship when Madagascar won independence from France in 1960 because they were not considered to be ethnically Malagasy.

Mahamadhoussen Chamimakatomme, a 58-year-old Karana woman, explains how she’s spent over 25 years seeking Malagasy citizenship. As part of her recent efforts, she paid a large sum for a 100 year “temporary” residency permit, only to be told soon afterwards that it was no longer valid unless it was redone with biometrics. “My residence card was thrown in the trash by a civil servant,” she laments.

Despite the significant challenges faced by the stateless Karana in Madagascar, a recent development is cause for celebration. On 25 January 2017, the Government promulgated a new law guaranteeing the equal right of citizens, regardless of their gender, to confer nationality on their children. Now, any child born to a Malagasy mother or father will be recognized as Malagasy.

UNHCR is hopeful that the government may take further steps to resolve the statelessness of the minority groups without nationality; in addition to the Karana, there are an unknown number of persons of Chinese, Comorian, and mixed descent who are stateless in Madagascar.

Few can argue with the words of Bachir Ibrahim*, an elderly Karana man, who simply but powerfully makes the case for the Karana to have equal access to Malagasy nationality: “We are here. We are your neighbors. When it rains it rains for all of us. When the sun shines it should shine on us all.”

*Name changed in order to protect the person’s identity at their request.

The Roma and other ethnic minorities of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

Mivtar Rustemov is a 47-year-old father. His 13-year-old daughter Lirije is one of his six children who remain unregistered. © UNHCR/Roger Arnold

The origins of the Romani people can be traced back to northern India, from where they migrated between the 13th and 15th centuries to Europe. From the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Roma form the largest group among the ethnic minorities that are stateless or at risk of statelessness.

Official numbers indicate that there are 54,000 Roma in the country, although unofficial estimates range from 110,000 to 260,000. The Roma have a unique ethnic identity and speak the Romani language, which distinguishes them from the majority Macedonian-speaking population.

“They were born here, how can I not get a birth certificate for my children?”

The statelessness of the Roma and other ethnic minorities is linked, in part, to the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Those who were legally residing in its territory at the time of the dissolution could acquire the nationality of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, by applying for naturalization within one year.

Many missed this short window of opportunity, largely due to lack of awareness, often remaining unaware of the fact that they were not citizens of the State in which they continued to live. “With an ID for foreigners, no one wants to employ you. We are reduced to poverty”, says Haidar Osmani.

Poverty, in combination with the inability to access public healthcare, has devastating health implications for many Roma, who are unable to pay for medical insurance from their own pockets. Haidar was forced to sell his house after he needed treatment for cancer. For the five members of his family, he has to cover around USD 240 per month for health insurance. Without a national ID card, he is not entitled to health insurance, social assistance or sustainable employment.

“I have made more than 20 formal applications for documents since 1991. I even visited the Ombudsman’s Office. They [the authorities] didn’t explain things to me, they just asked for documents that I don’t have”, he explains, defeated.

Almost all members of the community share his sentiments that they are not given clear instructions by the authorities, that they experience arbitrary treatment and that they are asked to produce documents they are unable to obtain.

Mivtar Rustemov, a 48-year-old Roma father of seven, has for years been trying in vain to obtain birth certificates for his six children who were born at home. “I cannot understand how this is possible. They were born here, how can I not get a birth certificate for my children? I want her [his daughter Lirije] to have the same opportunities as her friends have.”

Some of these issues are now being addressed. Discussions are ongoing on potential law reforms that would help the Roma access procedures for birth and personal name registration. The Ministry of Labor and Social Policy is also covering the costs of DNA testing for the most vulnerable Roma families to enable birth registration for children born at home who lack other evidence to prove their family links.

The Pemba of Kenya

Shaame Hamisi, 55, chairman of the Pemba community at Shimoni village in Kenya’s Kwale county, notes that statelessness has caused them to lack basic rights. © UNHCR/Roger Arnold

The Pemba, originating from the Tanzanian island of the same name, arrived in two major waves to Kenya. The first came in 1935-1940, in search of better livelihood opportunities. They settled at Kenya’s southern coast, which became an integral part of the country upon its independence in 1963. Notwithstanding their long presence on the coast, or the fact that most had lost their ties with the island of Pemba over time, these first arrivals and their descendants have never been recognized as Kenyan citizens.

The second wave of Pemba arrived in Kenya between 1963 and 1970, some seeking economic opportunity, but most fleeing the violence resulting from the 1964 Zanzibar Revolution. Although some were issued with Kenyan nationality identity cards, these were withdrawn under the repressive regime of President Moi and deportation orders against the Pemba were issued throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

“The biggest problem is the poverty caused by my statelessness.”

Notwithstanding these orders, many Pemba took refuge in the Kenyan bush, desperate to remain in the country that they had come to view as home. It is estimated that there are approximately 3,500 Pemba living in Kenya today.

Shaame Hamisi, a 55-year-old father of 13 and Chairman of the Pemba community, remains stateless and undocumented, despite the fact that his wife is a Kenyan national and is entitled to pass her nationality to him under the law. Shaame is a fisherman and spends long, hot days and starry nights on the Indian Ocean, trying to make a living to feed, clothe and educate his large family.

“The biggest problem is the poverty caused by my statelessness” he says. “Because I am stateless, I cannot get a fishing license. Without a license, I cannot go deep-sea fishing where the best catch can be found. I cannot afford my own boat, which costs 300,000 Kenyan shillings (approximately 300 USD), or the equipment to fish well. Without a Kenyan national ID card, I’m not eligible for bank loans to purchase those things. I must pay rent and fuel money to use my neighbour’s boat. Even if I could purchase a boat, I would have to register it in someone else’s name. A stateless person cannot own property. I feel belittled and disgraced by the situation that I am in.”

Omar Kombo, a jovial 48-year-old Pemba man with six young children, also feels bitter about the inequality he experiences as a result of being stateless. “The majority of us are fishermen” he says. “The Beach Management Unit deducts 10 Kenyan shillings for each kilo of fish that every fisherman on this coast sells. It is supposed to issue the dividends to all contributors for damage done to the boats during the season. Because we are Pemba we get nothing, even if our boats are broken. We are forced to participate in this scheme, but all the benefits are given to our brothers with Kenyan nationality.”

However, there are signs that this situation may change. In December 2016, the Kenyan Government recognized the stateless Makonde, another ethnic group living on the Kenyan Coast, as Kenyan nationals. The Government has also extended the deadline by which stateless persons present in the country since independence and their descendants can register for nationality. Members of the Pemba community are mobilizing, together with local NGOs such as the Mombasa-based Haki Centre and UNHCR, to advocate for their recognition as Kenyan nationals.

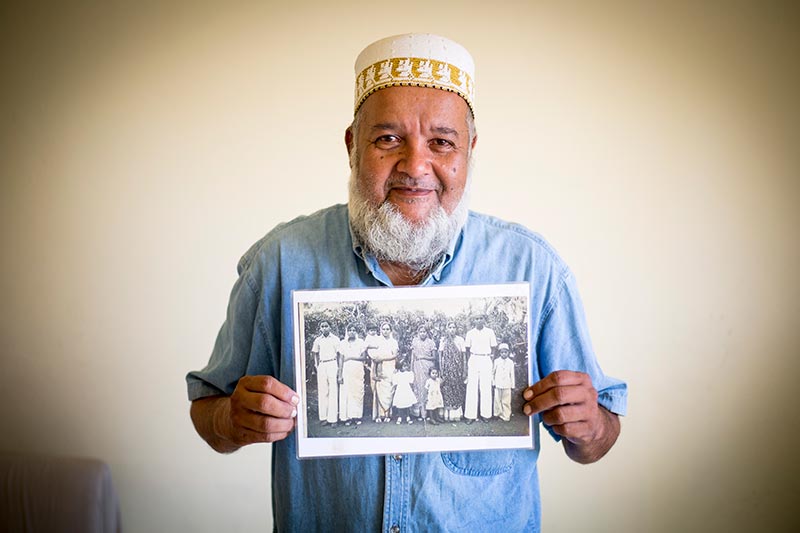

The Makonde of Kenya

“I felt like I was a slave. Now I feel like I have been born again,” says 51-year-old Amina Kassim, a formerly stateless member of the Makonde community in Kenya.

Shaame Hamisi, 55, chairman of the Pemba community at Shimoni village in Kenya’s Kwale county, notes that statelessness has caused them to lack basic rights. © UNHCR/Roger Arnold

The Makonde in Kenya is an ethnic tribe estimated to be around 4,000 in number who trace their origins to northern Mozambique. The community is mostly made up of labourers who were recruited by the British during the colonial period to work on sisal farms and sugar plantations. Other Makonde in Kenya are the descendants of exiled freedom fighters and refugees from the Mozambican civil war.

Despite most being resident in Kenya since its independence in December 1963, they were not recognized as citizens or included in any of the population registration databases. A 2009 national census report simply classified them as ‘others’. Tina Eric, a bright 22-year-old Makonde woman, recounts a painful memory: “One of my teachers in school singled me out one day and told the class that I was a Makonde. ‘Those are the ones that eat snakes’ she said. I was ridiculed after that. Even those who I thought were my friends did not fully accept me.”

“Before I got my national ID, I lived a debilitating life.”

Thomas Nguli, the respected 60-year-old Chairman of the Makonde community, confirms how these discriminatory attitudes, present even at the highest levels of government, degraded and excluded the community, stopping them from being viewed as fellow human beings, deserving of respect: “A certain political leader was asked how he viewed the Makonde and he shamelessly responded to the crowd that he saw us as cannibals – people who ate other people! After that, what hope did we have?”

Amina Kassim laments that “before I got my national ID, I lived a debilitating life. I could not engage in any meaningful business. I traded petty things, like Swahili buns. You don’t need a permit to sell them.”

Although in the past the Makonde in Kenya have, at various times, been invited to vote by both the Mozambican and Kenyan governments in their respective general elections, they have never been accorded the status of citizens by either of them.

In 2015, after decades of lobbying, the Makonde community successfully petitioned President Uhuru Kenyatta to review their case. In response, he called for the formation of an inter-departmental taskforce to look into statelessness in the country. With assistance from UNHCR, in November2015, the Taskforce completed a report with recommendations to register and naturalize stateless groups in the country.

Frustrated by delays in implementing the recommendations, in October 2016, hundreds of Makonde, young and old, supported by local civil society groups such as the Kenya Human Rights Commission, took part in a now legendary march from Kwale to Nairobi to personally request President Kenyatta to recognize them as Kenyan citizens.

On 13 October 2016, moved by the plight and efforts of the Makonde, and determined to resolve their situation, President Kenyatta apologized, saying “it has taken too long to give you justice as fellow Kenyans. Today is the last day you will be called visitors.”

He issued a directive to give effect to provisions in the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act (2011) that give stateless persons resident in the country since Kenya’s independence in 1963 (and their descendants), the right to be registered as Kenyan nationals. The President also officially recognized the Makonde as the 43rd tribe of Kenya, cementing the claim of future generations of Makonde to be recognized as citizens.