Desperate to “Come Home”

Twenty-eight-year-old “Diego L.” took a break from his flooring job in Amarillo, Texas, one chilly January afternoon to fill the tank of his Ford Focus at a nearby convenience store. As he rolled out of the parking lot to head back to work, Diego said an Amarillo police officer pulled him over, saying he had failed to yield properly. That stop led to his deportation in June, eighteen months later.

“I don’t have family here in Mexico,” he said in English, when Human Rights Watch researchers met him at a deportee reception center in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. He was born in Mexico City, the youngest of five children, and carried north with the family when he was two. “My parents still live in California – they sew for a factory in Santa Ana.”

Diego L. speaks with Human Rights Watch researchers at the Instituto Tamaulipeco in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. © 2017 Human Rights Watch

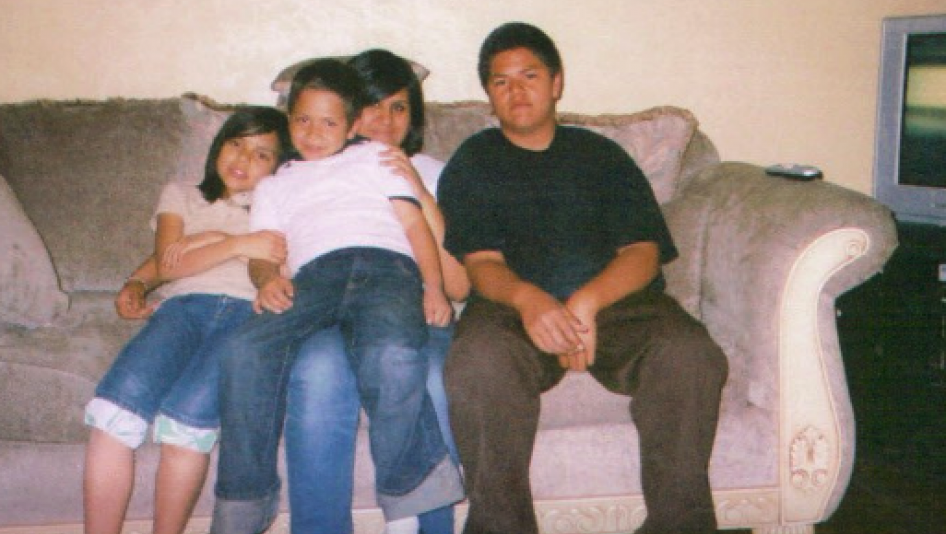

Diego’s US-born wife, “Amanda,” is desperately seeking legal remedies to get him back – her 9-year-old daughter and 7-year-old son miss him terribly. “He’s a good step-dad,” she told researchers by phone from Amarillo. “He’s never really done anything wrong. He was just born somewhere else.”

Diego’s immigration troubles started in 2012 when he and Amanda were arguing in their apartment – only verbally, they both insist – and a neighbor called the police. Diego said he calmly went out to meet them, and allowed himself to be cuffed. He pleaded guilty to obstructing police because, he said, “I didn’t know what I was doing. I wasn’t able to talk to anybody.” Diego served two months in Potter County Jail, and then a Border Patrol officer collected him. “They threatened me that if I didn’t sign a paper, I was going to go to prison and would never see my family again,” Diego says. “I didn’t read the paper, I just signed.”

That first deportation was hard on Diego, who got caught twice trying to cross back. “I didn’t know nobody,” Diego says. “I got robbed in Mexico, they took all my money, about US$100. When I was walking in the desert, I saw two dead bodies, lying in the dirt.”

When police stopped Diego at the convenience store on that January day, he couldn’t produce a drivers’ license – Texas doesn’t issue them to undocumented migrants. Police also found a small amount of methamphetamine in the car, which Diego says he has used occasionally in recent years, “like Red Bull,” to stay awake at work. This time, his stay in the Potter County Jail lasted nine months, and he was released to Immigration and Customs Enforcement, only to spend nine more months in detention. Although Amanda urged him not to sign anything – she was seeking ways to help him stay legally – Diego signed deportation papers.

Amanda said the first choice for them both is to get him back to Amarillo legally. But for the time being, Diego is fending for himself in a strange country. “This time, I got to know an old man in detention with me, so I feel a little safer,” he said, as he waited to use a phone at the deportee reception center. “He’s going to let me stay at his house.”

“His instinct,” said Amanda of Diego, “is just to come home.”