Reducing statelessness in Côte d'Ivoire one case at a time

Some 6,400 Ivorians have gained nationality certificates in the past two years as West African States redouble their efforts to eradicate statelessness.

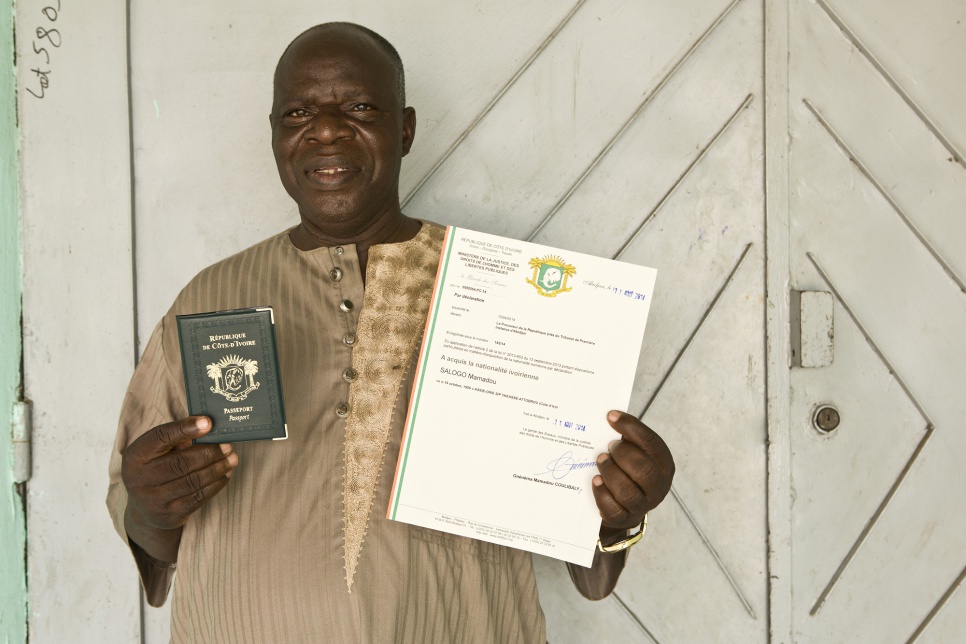

Mamadou Salogo proudly shows his Ivorian passport and the letter that proves that he acquired Ivorian nationality. © UNHCR/H. Caux

ABIDJAN, Côte d'Ivoire, Feb 25 (UNHCR) - When Mamadou Salogo began work as a security agent at a delivery firm in Côte d'Ivoire, the only issues that his employers cared about were whether he could show up on time and do his job.

But very quickly, the fact that he had no way to prove that he was eligible to live and work in his native Côte d'Ivoire made him the focus of taunts and hazing from his workmates that made keeping down the simple job impossible.

"'How did you get this job? We don't know who you are. You're not even from here!'" Salogo recalls them saying, convinced that being stateless was the reason he was eventually asked to leave his post.

The job loss was the last straw for Salogo, 59, who had experienced a lifetime of discrimination because he could not prove he was Ivorian. It began when he was forced to drop out of a school at a young age because he was not eligible for scholarships, which were reserved for nationals only.

Like some 10 million people worldwide who cannot prove their nationality - thousands of whom live Côte d'Ivoire - he was frequently insulted because of his status, and treated like an intruder everywhere he went.

"I suffered so much from being stateless. It's like I was a stranger in my own home. Statelessness is, at its most basic, a question of human dignity," he says, chatting at his home in Yopougon, a popular neighborhood in Abidjan, where he lives with his four wives and fourteen children.

Statelessness, or not being considered a citizen of any country, has disastrous consequences: bereft of citizenship, stateless people cannot go to school, work, own land or access healthcare; they are forced to live in the shadows, vulnerable to exploitation and invisible in the eyes of the law.

The circumstances that left Salogo stateless are common. He explains that his parents were originally from Haute-Côte d'Ivoire, in present-day Burkina Faso, and had settled in Côte d'Ivoire to work in the cocoa and coffee plantations.

"Since neither had been registered at birth or had papers proving who their parents were, it never occurred to them to do so for me. So, like my parents, I had no national identity papers!"

Many of Salogo's friends are in a similar situation. "Living in this country without a nationality was a real source of frustration. I had ambitions to become a high-level official but I could not even go to university because I was not recognized as Ivorian," explains Moussa Ouedraogo.

Mamadou poses with his four wives and some of his 14 children in front of their house located in Abidjan's Yopougon neighbourhood. © UNHCR/H. Caux

During the post-electoral violence in Côte d'Ivoire in late 2010 that forced around 300,000 people into exile, life for Salogo became even more difficult. Without a nationality, he was automatically seen as suspicious and was identified as either allied with one of the warring parties, or as a foreigner trying to wreak havoc in the country. "It was hell, my family and I felt unsafe wherever we were," he recalls.

Today marks of the first anniversary of the Abidjan Declaration, which was adopted by all West African States as a pledge to reduce and ultimately eradicate statelessness in the region. Significant progress has been made in the past year in reducing cases of statelessness - among them that of Salogo.

His situation was finally resolved in June 2015, when his application to the program to acquire Ivorian nationality through declaration was accepted. He is among 6,400 Ivorians who have gained nationality certificates since April 2014, and now has the same rights as all other Ivorian citizens.

"My life has changed a lot since then. People look at me differently, I feel like I'm finally on equal footing with others. I can go to work without fearing that I will be mocked. My children can now acquire Ivorian nationality as well, and go to school."

In Côte d'Ivoire, for instance, UNHCR is supporting a government-led program that allows people born or residing in the country since the time of independence to acquire Ivorian nationality through a simple, non-discretionary method. In addition to the nationality certificates that have already been distributed, thousands more applications are still under review.

"The Ivorian Government's program is an important first step in reducing statelessness but a lot more needs to be done," says Mohamed Askia Toure, UNHCR Representative in Côte d'Ivoire. "It should be extended indefinitely, as there are still thousands of people who do not have a nationality in Côte d'Ivoire and who need urgent protection and assistance".

By Nora Sturm in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire