Summary

More than three years after South Sudan’s conflict began in the capital Juba in December 2013, the war has spread to the Greater Equatoria region, in the southern part of the country, which had until recently been largely spared from the fighting. In the past year alone, over one million civilians, many of them from villages in this region, have fled to neighboring countries. More than 700,000 crossed into Uganda alone. As elsewhere in South Sudan, the conflict in the Equatorias has played on pre-existing ethnic and communal tensions and is marked by serious abuses committed against civilians by government soldiers and opposition fighters.

In May 2017, Human Rights Watch researchers visited two refugee settlements in northern Uganda and interviewed over 100 South Sudanese refugees who fled from the Kajo Keji and Pajok areas, south and southeast of Juba, between January and May of this year. Their accounts of serious violations at the hands of government soldiers match the wider patterns of violations observed since the government began to conduct counterinsurgency operations against opposition forces in the south and west of the country in late 2015.

Despite the signing in August 2015 of the Agreement for the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS), between the government and the armed opposition led by former vice-president Riek Machar, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-in Opposition (the “IO”), attacks on civilians have now become commonplace in the previously stable southern and western regions of the country. Fighting between government forces and the IO in the capital Juba reignited in July 2016.

The conflict reached the western parts of the Greater Equatorias region in late 2015, and expanded southeast in more recent episodes of violence. Human Rights Watch researchers documented the unlawful killing of at least 47 civilians from the Kajo Keji area, in the former state of Central Equatoria, by government forces between June 2016 and May 2017. Researchers also documented the unlawful killing of at least 13 men and 1 woman, all civilians, by government forces during a large-scale attack on the town of Pajok, in the former state of Eastern Equatoria.

The regions of South Sudan formerly known as Western Bahr el-Ghazal, Western Equatoria, Central Equatoria and Eastern Equatoria states have been the most severely impacted by government counterinsurgency operations since late 2015.

Witnesses and victims of abuse interviewed by Human Rights Watch also reported dozens of cases of arbitrary detention by the army, including cases in which victims were held in shipping containers sometimes for long periods; and enforced disappearances, whereby authorities refuse to acknowledge the detention or disclose the whereabouts or fate of a detainee. Soldiers beat and tortured the vast majority of detainees, according to victims and relatives who spoke to Human Rights Watch.

The cases described in this report are part of a much larger body of similar abuses documented since January 2016 by Human Rights Watch in the Greater Equatoria and Bahr-el-Ghazal regions -- in and around the towns of Yambio, Wau, Juba and Yei. The accounts show a clear pattern of government forces unlawfully targeting civilians for killings, rapes, arbitrary arrests, disappearances, torture, beatings, harassment and the looting, burning and destruction of their property.

In many instances, government soldiers fired indiscriminately in populated areas in what seems to have been retaliation for IO hit-and-run attacks on their forces, failing to take any precautions to protect civilians. In other cases, indiscriminate shootings and other tactics designed to instill fear in the population seemed to have the goal of displacing the civilians from rebel-held areas in an apparent effort to expose rebel fighters. The decision of rebels to encourage civilians from their own communities – particularly in the Equatorias and Wau area – to leave cities controlled by government forces, have further contributed to displacement.

The ethnic dimension to these crimes, with predominantly Dinka forces targeting members of other ethnic groups suspected of supporting the opposition, is clear. Exacerbating these divisions is a long legacy of the Sudanese government’s support for some of the same ethnic groups during the long southern independence wars.

The gravity of the abuses since the new war began in December 2013 and the ethnic dynamics that accompany many of these abuses is extensively and publicly documented by international organizations such as the United Nations and the African Union, non-government organizations, such Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, and by national investigative committees reporting to President Salva Kiir. However, both parties to the conflict have failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures to stop the crimes or hold those responsible to account.

The proposed Hybrid Court for South Sudan (HCSS), provided for under the ARCSS, raised hopes that further atrocities fueled by decades of impunity and de facto amnesties would finally be curtailed. Under the peace agreement, the court is to be composed of South Sudanese and other African judges and staff, and to be established by the African Union Commission.

Nearly two years after the ARCSS was concluded, the court has yet to be established, and for more than eighteen months, almost no tangible progress toward its establishment was made. Serious crimes continue to be perpetrated, and concern that the court would never materialize increased.

Although the parties to the conflict agreed in principle to the HCSS under the ARCSS, a key challenge for the HCSS was that South Sudan’s government had yet to substantively engage with the AU Commission on the establishment of the court.

On July 21, AU Commission, South Sudanese, and UN officials met in Juba to discuss the Hybrid Court for South Sudan and agreed on a roadmap for the court’s establishment, including finalizing the court’s statute by the end of August. If implemented, the roadmap could represent a breakthrough in advancing justice for victims of grave crimes committed in South Sudan.

The UN Security Council failed to impose an arms embargo on South Sudan and couldn’t agree to impose additional individual sanctions on two South Sudanese implicated in serious human rights abuses. These repeated failures on the international stage have contributed to the atmosphere of impunity enjoyed at home by South Sudanese leaders on both sides, and seems to have emboldened their stance.

The impact of the violence and persistent abuses against the civilian population is devastating. Acute food insecurity is widespread. Six million South Sudanese, almost half the country’s population, face severe food shortages. The outflow of refugees continues at an alarming rate, uprooting entire communities and effectively emptying swathes of land, and 1.9 million civilians remain internally displaced, with some sheltering on UN bases. The crisis is costing the international community billions of dollars.

Rather than allow this situation to fester, international and especially regional actors should take all means necessary to stop violations against the civilian population and provide meaningful accountability. These include enacting and implementing an arms embargo, additional individual sanctions, and accelerating the deployment of the UN Regional Protection Force, authorized by the UNSC in August 2016 to bolster the mission’s protection capacity.

The AU Commission should move ahead with establishing the Hybrid Court for South Sudan. While positive engagement with the government of South Sudan is helpful, the AU Commission has the authority to establish the court with or without the engagement of the government and should proceed on that basis if necessary. If a credible, fair and independent hybrid court does not progress, the option of the International Criminal Court (ICC) remains and should be pursued. As South Sudan is not a party to the court, the UN Security Council would need to refer the situation to the ICC in the absence of a request from the government of South Sudan.

Based on cumulative evidence from reporting since December 2013, investigations into those responsible for committing war crimes and crimes against humanity should include investigations into the potential criminal responsibility of President Kiir, rebel leader Riek Machar and their respective top military commanders. All those against whom there is credible evidence of criminal responsibility should be charged and prosecuted in accordance with international fair trial standards.

Recommendations

To the Government of South Sudan, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and Allied Militias

- Issue clear, public orders to all armed forces, military intelligence, and allied militias to prevent and end all abuses, including unlawful killings, arbitrary detentions of civilians, torture, enforced disappearances, crimes of sexual and gender-based violence, and theft and looting of civilian property.

- Investigate and hold accountable those responsible for serious abuses, including commanders for abuses committed by forces under their control.

- Support and facilitate the African Union Commission’s work in promptly establishing the Hybrid Court for South Sudan as committed to in the August 2015 Agreement for the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS), including by implementing the July 21 roadmap agreed to by government, AU Commission, and United Nations officials on the court’s creation.

- Exclude amnesty for serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law from any future peace agreement or arrangement.

- Ensure unimpeded access for humanitarian aid organizations to all populations in need of assistance and ensure all staff, facilities and supplies are protected from attacks, looting or diversion.

- Lift restrictions on movements by the United Nations Mission to South Sudan (UNMISS) and comply with the Status of Force Agreement, and on Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC) ceasefire monitors.

- Fully cooperate with investigation and monitoring activities by the UNMISS, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, JMEC ceasefire monitors, and eventually the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, including by providing information requested and facilitating access.

- Negotiate and agree with the UN Country Task Force for Monitoring and Reporting on an updated action plan to end all grave violations against children for which the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) has been listed by the UN Secretary-General, including to end the killing and maiming of children.

To the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in-Opposition (IO) and Other Armed Opposition Groups

- Issue clear, public orders to all combatants to prevent and end all abuses, including killings, abductions and forced recruitment, beatings and crimes of sexual and gender-based violence.

- Commit to ensuring a clear operational distinction between combatants and civilians, notably by wearing uniforms and refraining from using civilian infrastructure to launch attacks on government forces.

- Immediately investigate and suspend senior commanders who bear prima facie responsibility for serious abuses allegedly committed by forces under their control.

- Exclude amnesty for serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law from any future peace agreement or arrangement.

- Facilitate unimpeded access to territory under your effective control for impartial humanitarian aid organizations and ensure all staff, facilities and supplies are protected from attacks, looting or diversion.

- End any restrictions on movements by UNMISS and comply with the Status of Force Agreement, and on JMEC ceasefire monitors in territory under effective control.

- Fully cooperate with investigation and monitoring activities by the UNMISS, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, JMEC ceasefire monitors, and eventually the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, including by providing information requested and facilitating access.

To the United Nations’ Security Council

- Impose a comprehensive arms embargo on South Sudan’s territory directing the existing UN panel of experts to monitor and report back on implementation of the embargo.

- Impose additional targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on individuals implicated in violations of the arms embargo or serious violations of international humanitarian or human rights law.

- Renew the UNMISS mandate prior to its expiry in December 2017 with a mandate that authorizes it to continue to carry out its protection of civilians and human rights protection functions, and specifically directing it to collect disaggregated data on abuses against persons with disabilities.

- Ensure prompt deployment of the Rapid Protection Forces, authorized on August 12, 2016, to bolster the mission’s protection capacity.

- Reaffirm UNMISS human rights division’s mandate to report findings promptly and publicly, including by urging the military force component of the mission to provide human rights officers with the physical protection needed to allow them to investigate allegations of serious violations in remote areas.

- Convene an open session of the UN Security Council to discuss progress on efforts to secure justice for the worst crimes committed in South Sudan, including any continued challenges to the operationalization of the Hybrid Court for South Sudan provided for in Chapter V of the ARCSS, and plans to ensure perpetrators are held to account without further delay.

To the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

- Ensure the OHCHR Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan is staffed and able to carry out its mandate, in particular to collecting and preserving evidence for criminal accountability processes.

- Ensure increased public reporting by the human rights division of UNMISS; issue more frequent public statements by the High Commissioner.

To the African Union Commission

- Consult with civil society and other relevant stakeholders on the court’s draft statute and other legal instruments.

- Determine the location of the court, taking account of security risks to convening the court in South Sudan.

- Implement fully the July 21 roadmap for the creation of the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, including finalizing the court’s statute by August 31.

- Offer regular updates on progress on the establishment and functioning of the Hybrid Court for South Sudan.

- Impose a comprehensive arms embargo on South Sudan and individual sanctions, including asset freezes and travel bans, on individuals implicated in violations of the arms embargo and serious violations of human rights.

To the Inter-Governmental Agency for Development (IGAD)

- Press South Sudan to cooperate with the AU Commission on prompt establishment and operationalization of the Hybrid Court for South Sudan.

- Request the AU and the UN to impose a comprehensive arms embargo and targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on individuals responsible for violating the arms embargo or serious violations of international humanitarian law.

- Exclude amnesties for serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law from any future peace agreement.

To the European Union, United States and Other States

- Impose additional targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on individuals implicated in serious violations of international humanitarian or human rights law.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews with South Sudanese refugees in Uganda, conducted in May 2017 in settlements in Lomwo, Adjumani and Moyo counties. The Background section of this report draws on previous research conducted by Human Rights Watch since the beginning of South Sudan’s new war in December 2013.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 112 South Sudanese victims, witnesses and humanitarian workers between May 14 and 31, 2017. Researchers identified the interviewees based on their place of origin, focusing on those from Kajo Keji county and from Pajok, in the newly-formed Ayaci county, and interviewed refugees from most of Kajo Keji’s payams (administrative sub-units) and from all four main neighborhoods of Pajok.

In some cases, because researchers could not access the site of abuses, it was not possible to independently corroborate the allegations of abuses. However, researchers sought to determine the credibility of many of the allegations by interviewing multiple people who witnessed the same events.

The names of the interviewees have been withheld for security reasons. Most interviews were conducted at their homes in the refugee camps, and in private, with the aid of an interpreter and translators from civil society and church organizations.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to the local context, the broader conflict and the abuses they had been victims of or witnessed. Human Rights Watch sought the consent of interviewees, informed them of the purpose of the interview and the sorts of issues that would be covered. Each interviewee was informed that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence.

Researchers took steps to try and minimize the risks of re-traumatization when conducting interviews, and, where appropriate, took steps to facilitate contact with international aid organizations providing medical, counselling or reunification services. No incentives were provided to interviewees.

I. Background

South Sudan’s new war began in December 2013, a mere two and a half years after the country’s independence, when troops loyal to President Salva Kiir – a Dinka – clashed with those of then Vice-President Riek Machar – a Nuer – in the capital Juba. Within hours, government troops were conducting large-scale killings of Nuer civilians in various parts of Juba, spurring civilians to move en masse towards United Nations’ Mission to South Sudan (UNMISS) bases and the bush.[1]

Along with a few supporters, Machar fled to Jonglei, where he received assistance from defecting Nuer commanders and soldiers who would later make up the bulk of his Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-in-Opposition, also known as “IO.”[2]

As the conflict spread to Bor, Bentiu, Malakal and across the Greater Upper Nile region the two sides carried out large-scale offensives and counteroffensives with some key towns changing hands multiple times.[3] The violence included horrific attacks on civilians, massive destruction of property, and prompted mass displacement to the UNMISS bases and other displacement sites.[4] By June 2017, 3.9 million South Sudanese had fled their homes, including 1.9 million refugees and over 230,000 people sheltering in or near UNMISS “protection of civilians” bases.[5]

Often targeting victims based on ethnicity, both government and opposition forces have killed thousands of civilians, committed acts of sexual violence, looted and destroyed civilian property and unlawfully detained and tortured civilians. Both sides have also forcibly recruited and used child soldiers. The United Nations, the African Union, Human Rights Watch and others have documented these patterns of abuse.[6]

The UN Mission to South Sudan (UNMISS) has struggled to implement its mandate to protect civilians. The government’s recurrent denials of access and restrictions of movement to many affected areas have negatively impacted the capacity of the UNMISS and other monitoring bodies to implement their respective mandates. The UN’s Regional Protection Force, authorized after the Juba fighting in 2016, has yet to be fully deployed.

Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan

In August 2015, under the auspices of a body of regional states known as IGAD, the parties signed the Agreement for the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan, known as ARCSS. [7] The agreement – in effect a power-sharing accord – established a transitional government of national unity in which Machar’s opposition would assume the vice-presidency and a number of cabinet position and governorships until new elections were scheduled at the end of a 33-month transition period.

The agreement also provides for the “cantonment,” disarmament and eventual reintegration of opposition fighters and for justice and reconciliation mechanisms to be set up to provide accountability for crimes committed since 2013.[8] Key amongst these is the establishment of a Hybrid Court for South Sudan (HCSS) with the authority to try genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other serious crimes committed since the current conflict began.

ARCSS also established a Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC) tasked with supervising the implementation of the agreement, and a Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism (CTSAMM) to monitor violations by the parties. However, neither the government nor the opposition ever fully adhered to their obligations to ensure full implementation of the terms of the peace deal.[9]

As the parties negotiated the agreement, fighting continued, notably in the former Unity state, and spread to areas previously untouched by conflict.[10] Starting in 2015, local armed groups emerged in Greater Bahr-el-Ghazal and the Greater Equatoria regions – especially in areas with pre-existing grievances against the perceived Dinka domination in the Juba government – and, in some cases, joined Machar’s opposition. Some of these groups appeared motivated by benefits they hoped to obtain under the ARCSS security arrangements and others pointed to the central government’s unilateral restructuring of South Sudan’s state system as the basis for their opposition.[11] In response to the emergence of these groups, the government began to carry out heavy-handed, highly abusive counter-insurgency operations meant to flush the opposition out of the areas immediately after the signing of ARCSS.[12]

Immediately after signing the peace agreement, the government issued a list of reservations, which stated that it would limit its recognition of opposition troops eligible for cantonment to those who fought in the Greater Upper Nile. [13] This limitation excluded rebels who were based in the south and west of the country and thwarted Machar’s ambition to expand his presence near the capital. Meanwhile, Machar repeatedly delayed his return to Juba, in spite of the agreement.

Machar finally returned to Juba in April 2016 under pressure from international supporters of the peace deal. Two months later, in early July, his troops and those of the government clashed in the capital following weeks of building tensions around the transitional security arrangements.[14] During the fighting, government forces attacked civilians in Juba, including those sheltering at UN protection of civilians sites and Machar fled the capital.[15]

Weeks after Machar fled into the Democratic Republic of Congo, President Kiir appointed Taban Deng Gai, a former lieutenant of Machar, as his new first vice-president in a move to preserve the government’s legitimacy stemming from the power-sharing agreement.[16] However, the armed factions allied to Machar refused to join Deng. An amnesty declared by Kiir in the aftermath of the July fighting did little to convince the majority of the rebels to lay down their weapons.[17] Since then, conflict has continued and expanded geographically, with a pattern of abuses against civilians of minority ethnic groups, whom the government believes to support armed opposition groups.[18]

The violence has turned South Sudan into the site of one of the world’s largest humanitarian crisis.[19] To date, more than 3.9 million South Sudanese, or over a third of the population, have been forced to flee their homes to internally displaced camps or neighboring countries.[20] The humanitarian consequences of the fighting and displacement have also led to severe hunger; in February 2017, famine was declared in 2 counties of former Unity state.[21] Areas in the Equatorias that were once the food baskets of the country are now food insecure. Some 6 million South Sudanese, or half the population, are now in need of humanitarian assistance.[22]

Legacy of the Ethnic and Inter-Communal Tensions

The conflict that began in 2013 has spread by playing on historical grievances and divisions. Sudan’s history of supporting certain groups to fight alongside its armed forces against the southern rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) during Sudan’s second civil war drove a wedge between South Sudan’s ethnic groups.[23]

These divisions have resurfaced in the current war, as many of the commanders who joined Machar’s IO share a common history of fighting against the SPLA during the Sudanese civil war.[24] However, some of the conflict dynamics are new.

The divisions are compounded by a decades-long sense of resentment among non-Dinka groups against what they perceive as the “Dinka domination” of the government and army.[25] Further aggravating the tensions in the country, the government took the unilateral decision in December 2015 to divide the country’s initial 10 states into 28 separate entities.[26] A year later, four more states were added to the list.[27] The decisions have been widely interpreted as an attempt to decrease the influence of a number of ethnic groups that were either seen as allied to Machar’s opposition or had historical land disputes with the Dinka.[28]

The Spread of Conflict West and South

Beginning in late 2014, the IO began to recruit a number of prominent commanders in the Greater Equatoria and Bahr el-Ghazal areas in an effort to diversify the largely Nuer movement.[29] Other armed groups, such as that of SPLA general Thomas Cirillo, who defected in February 2017, are also said to be operating in the Equatorias and Bahr el-Ghazal regions.

In addition, large numbers of Dinka cattle-herders moved in late 2015 to fertile lands and more developed towns, increasing tensions between local farmers and cattle owners.[30] Pre-existing and new local defense groups surfaced as a result, and some declared allegiance to Machar’s IO in parts of Central and Western Equatoria --notably in and around Wondoruba, Mundri, Maridi and Yambio.[31]

Through these dynamics, Machar diversified his opposition movement, which was until then largely composed of Nuer commanders and fighters. IO recruitment in the Equatorias also provided Machar with an armed presence near the capital as he prepared to return to Juba in April 2016 as part of the peace process.

But as the opposition groups began to clash with government forces in the lead up to and aftermath of the peace agreement, the government beefed up its presence to the south and west of the country and carried out abusive military operations. These operations intensified as Machar fled the capital in July 2016, following a renewed round of fighting between his forces and those of the government. As described below, his flight through the Equatorias also brought more skirmishes between government and opposition forces in the region.

Counter-Insurgency Tactics

Beginning in late 2015, a number of state governments in the Equatorias and Wau areas requested troop reinforcements to respond to increased activity by the rebels. The SPLA, faced with a shortage of trained soldiers after large numbers of Nuer soldiers defected to Machar’s IO in 2013-14, deployed primarily Dinka soldiers, including newly-recruited and poorly-trained forces known locally as the “new forces” or Mathiang Anyoor.[32]

The deployment of the Mathiang Anyoor in these areas, where there were already tensions between non-Dinka farmers and Dinka cattle herders, further alienated local communities and at times drove them into the opposition’s arms.[33]

The conflict in the Equatorias region and the Wau area has come at a heavy price for civilians. Government operations, often prompted by opposition ambushes on government soldiers, routinely involved unlawful reprisals against civilians who live in rebel areas and share their ethnicity. Many of the government’s counterinsurgency tactics -- recalling some of those used by the Sudanese Armed Forces during the war against the SPLA-- include militarizing the main towns; creating a climate of fear through raids on neighborhoods or villages deemed sympathetic to the opposition; conducting arbitrary arrests, detention and torture of local youth; restricting freedom of movement between towns and surrounding villages; and “road cleaning” operations to flush out rebels and secure roads between main towns. [34]

In the Yei area alone, the UN documented 114 killings of civilians by pro-government forces between July 2016 and January 2017, and by November 2016 had received information that the SPLA and National Security Services had arrested and arbitrarily detained 120 civilians.[35] In an October 2016 visit to Yei, Human Rights Watch researchers found that government troops were responsible for a dozen killings inside of town and the arbitrary detention of scores of civilians.[36] In the Yei, Morobo and Kaya regions, analysis of satellite imagery acquired by the UN in March 2017 showed over 18,300 structures destroyed, including civilian houses, likely in connection to the fighting.

The opposition has also abused civilians in their midst. They have at times forcefully recruited new fighters from local populations and also committed abuses against them, including targeted killings of Dinka and Nuba civilians and community leaders suspected of collaborating with the government, and rapes in the Yei area.[37] In Kajo Keji and Pajok, Human Rights Watch heard accounts of rebel abuses but was unable to corroborate them. The rebels' stronger family and cultural connections to the communities living in the areas where they operate also likely contributed to limiting the number of abuses they committed against civilians.

The failure of both sides to discriminate between civilians and armed combatants and their regular targeting of civilians on the basis of their ethnic affiliation, lie at the root of the dire human rights and humanitarian crises that have plagued several regions of South Sudan since December 2013, and now plague the Equatorias and Wau areas.

II. Conflict and Abuses in Central and Eastern Equatoria

Throughout the spring of 2016, the government deployed additional numbers of largely Dinka troops, including Mathiang Anyoor, in strategic locations south of Juba to counter growing activity by Machar’s opposition forces. Following Machar’s flight from Juba and into Central Equatoria after the July 2016 violence, IO forces began to ramp up attacks against government troops and vehicles, prompting the government to heighten their military activity in the areas.[38]

Over the summer of 2016, government troops and other security forces, including National Security and Military Intelligence, began to clamp down on the civilian populations they believed were harboring rebels in the Lainya, Yei, Morobo, Kajo Keji and Magwi counties of former Central and Eastern Equatoria states.[39] The opposition fighters, who often controlled smaller villages, encouraged civilians to leave the towns, and staged regular hit-and-run attacks against government installations and convoys. Government forces then retaliated against civilians in the area, using abusive counterinsurgency tactics such as unlawful killings, arbitrary detentions, torture and enforced disappearances.

The fighting and abuses in Central and Eastern Equatoria have prompted waves of displacement to neighboring countries - notably Uganda – with some of the latest arrivals coming from Kajo Keji and Pajok where government forces carried out counterinsurgency operations.

Throughout the Greater Equatoria region, UNMISS and JMEC/CTSAMM regularly face access restrictions from government forces when they tried to investigate and document abuses. In Pajok, for example, a joint UN and CTSAMM patrol tried to access the locality on April 5 but was turned back by SPLA soldiers. Observers tried again on April 11 and reached Pajok on April 12. Many places in the Greater Equatoria remain off-limits to UN and aid groups.

Kajo Keji

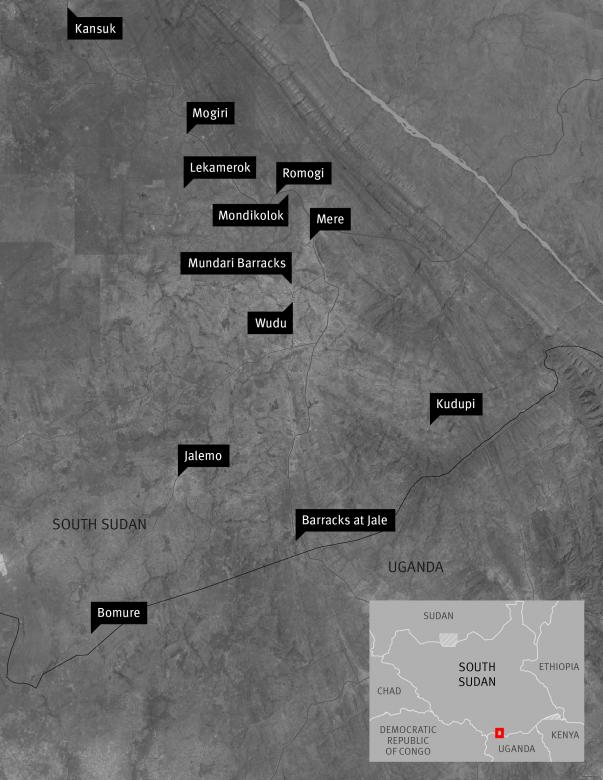

By early June 2016, new government forces coming from Juba and presumed by civilians to be Mathiang Anyoor reached Kajo Keji county, at the south-eastern corner of the Yei River state. While the SPLA already had a presence at the “Mundari” barracks in Kajo Keji’s Wudu town, under the command of John Camillo since 2016, the incoming forces were posted further north in a small town called Kansuk and at the border with Uganda in Bomure and Jale.[40]

The opposition forces in the area were reportedly led by Frank Matata, a former SPLA aide who defected to the IO in late 2014 and was appointed by Machar as the Yei River stateopposition governor in August 2015.[41] Locals interviewed by Human Rights Watch said while the opposition fighters mostly stayed clear from local communities and did not have bases inside populated areas, the forces on occasion entered villages and committed abuses against civilians, including forced recruitment, rapes, beatings and possibly executions.[42] For example, in one case reported to Human Rights Watch, three suspected opposition soldiers stopped three girls returning home from boarding school, and raped them in the bush.[43] The vast majority of crimes reported were allegedly committed by government soldiers.

The first episode of violence was a rebel ambush of government soldiers. On June 9, 2016, government soldiers arrived in Kansuk. The Mundari barracks commander, John Camillo, told the community the soldiers were there to protect them from the rebels. On June 11, a market day in Kansuk, rebels attacked the new government base. The fighting led to the deaths of several government and opposition fighters, as well as a teacher named “Baji.”[44] Following the attack, Peter Majok was appointed commander of the Kansuk base.

Several witnesses told Human Rights Watch that Camillo and Majok publicly accused the population of supporting the opposition in the aftermath of the attack during community meetings and ordered soldiers “to shoot everyone if you find rebels in a community.” [45]

Killings by Government Forces

Human Rights Watch documented the cases of 47 civilians alleged to have been killed by government forces in Kajo Keji county between June 2016 and May 2017. The total toll is likely to be much higher.

In many cases, the killings documented by Human Rights Watch resulted from indiscriminate shooting during attacks on civilian targets, such as markets. In other cases, groups of soldiers purposefully targeted and executed certain individuals, including children, people with disabilities and older people. Local commanders made public statements accusing the civilian population of supporting the opposition, appearing to legitimize the attacks on civilians.

In many cases, soldiers attacked people in their homes. A middle-aged woman from Romogi, some 10 kilometers to the southeast of Wudu, told researchers that her husband and two of her children, aged 5 and 10, were killed when soldiers came to their home on a Tuesday afternoon in January 2017.[46]

I was cooking dinner when about 10 soldiers came to our house. My son told me they had come and my husband went out. They shot him. Then my other son followed him out and they shot both boys. One soldier ran after me, caught me and severely twisted my arm. He only had a knife and I managed to get away. And I just ran. I spent 4 days hiding near a river and I drank water with one hand and ate the soil. When I came out, there were no people at home so I came to Uganda. With one arm, how do I care for the children and my mother? I want to commit suicide.

In a similar January 2017 incident in Romogi, a man told researchers that soldiers killed Moses Woja, his 20-year-old cousin with a psychosocial disability: “About 11 soldiers came and kicked the door of the house. I had fled to the bush when I heard that the soldiers were there. Moses stayed behind and he was slaughtered,” he said. “They used a knife to slaughter him at the back of his neck. We found the body later and did a burial. We left for Uganda right after.”[47]

In another January 2017 example, soldiers abducted Oliver Rumbe, a man they suspected of being IO, and killed him. His step-daughter told researchers how four armed men came to their home at night in Mere, a government-controlled town, around 8pm, and took Rumbe into the bush. “The next day, we went to the police and they came with us to our home. They followed the foot prints into the bush and they came back saying they had found the body,” she said. “His testicles were tied and the rope was going around his neck and he choked. That’s how they had killed him.”[48]

One of the most violent government attacks was at Mondikolok, a town near Wudu. On January 22, 2017, as people gathered at the church for Sunday service, soldiers from the Mundari barracks arrived on foot and began to shoot through the crowded marketplace. They killed 6 people on the spot.

Witnesses to the attack told researchers that opposition fighters would sometimes come to the market but that it was difficult to identify them because they did not always wear uniforms. [49] They said no opposition soldiers were visible that day, and they did not know what prompted the soldiers to attack.

A woman in her late 50s who was at the market that day told researchers that the soldiers, who arrived from the Wudu barracks, parked their vehicle outside of Mondikolok, entered the town on foot, and began firing through the market:

As we ran to the bush, the bullets were flying all around us. Some of us were crawling. I was running with Jane Sumuri in a bigger group, and then we got separated. When I reached the bush, I heard that Jane had been killed. We went back to Mondikolok when the soldiers left and we found six bodies. Jane had been shot in the vagina and her whole body was burned. She had five children and her husband died a long time. I don’t know what her children’s fate will be now.[50]

A 30-year-old relative of another victim told Human Rights Watch that she had come to the market that day with Samuel Wori, her brother-in-law, to buy a few goods prior to departing for Uganda:

When the soldiers started to shoot, I tried to take Samuel to safety, but he had a disability and I could not lift him. He said: “Since there are many bullets, let me here down on the ground and run.” So I left him under a mango tree and sneaked to take cover in a house. But soldiers found him and shot him in the mouth. The bullet exploded his skull and everything came out. Then the soldiers lay the body out under the tree and straightened his legs, which were paralyzed. I think they did this because they realized he had a disability and didn’t want people to think that they had shot someone who could not be an enemy.[51]

The January 22 attack on the Mondikolok market shook the communities of Kajo Keji. Most of the refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch referred to it as one of the key incidents that motivated them to leave South Sudan.

A retaliatory attack by rebels on the Mere police station two days later prompted many thousands more to leave for northern Uganda.

In February 2017, Pio Abu Saleh, a middle-aged man, was found dead in Jalemo, a market town located 5 kilometers north of the border, presumably killed by soldiers from the nearby Bomure military base. His head and hands had been severed from his body.[52]

In March 2017, opposition forces claimed that they briefly captured the Kajo Keji county headquarters following clashes with government forces, a claim that may have prolonged government forces’ presence – and their abuses– in the area.[53]

In early April 2017, government forces attacked the Jalemo market, which at that time was under control of opposition forces, killing at least four civilians and one opposition fighter.[54] A 43-year-old teacher and shop owner recounted the incident:

I took a motorcycle to Jalemo to collect some things. The IO was in control at the time. At some point, a khaki car full of soldiers arrived. It was mounted with a doshka. There were many soldiers and they started shooting… They shot at me in a field some distance away but the bullet did not hit me. I narrowly escaped and went to Mekor to rest. Then I went back to Jalemo to get my bike, but it had been stolen. I saw 4 dead bodies. That of Anthony Joghar is one of them and three others whom I did not know.[55]

A 45-year-old mother of four from Bori Boma told Human Rights Watch that her husband went missing at the time of the attack on Jalemo, and does not know where he is: “There was a fight in the Jalemo market and in the fight, the group that my husband was with was scattered and he never came back,” she said, “I heard that he was arrested and his relatives are trying to follow up, but we really don’t know. I hope that he was taken by the opposition or the government because I cannot go for the conclusion that he might have been killed.”[56]

Other killings occurred when people returned home from Uganda to collect food or other supplies.[57]

An older blind mother told Human Rights Watch that her youngest son, a man named Ojo, was killed in February 2017 by Dinka men, suspected to be soldiers, as he walked back to Uganda from Jalemo, where he had gone to collect food.

“He decided to go back to collect some maize because they lacked food and his wife was 5 months pregnant,” she explained. On the way back, Dinka men attacked and killed him, she said. “We did not find his body for a long time and had to send a team to look for it. Finally, they found his corpse by a riverbank.”[58] The family brought the body back to her compound for burial.

In mid-April 2017, armed Dinka men, presumed to be soldiers, killed three men who had travelled from the refugee settlements to Lekamerok, a few kilometers from Mondikolok, their relatives told Human Rights Watch.[59] The three men, Julius Beka, Mande Longat and Marle Bennett, were shot after spending one night in their village where they had gone to collect food: “On Saturday, as they prepared to come back, the Dinka arrived and began to shoot them. We learned about it from neighbors who are still in the area,” the wife of one of the deceased men told researchers.

In some cases, soldiers also killed older men and people with disabilities who remained behind when most civilians fled.

In mid-April, soldiers killed three older men who had been tasked with taking care of 225 heads of cattle, as the men were taking the cows toward Uganda. The son of one of the men told researchers how soldiers intercepted them in Laikor, near the border. “They wanted to take the cattle. They put my father and the two other men in line and shot them. The Dinka men wore the uniform. We know because there were two young boys on bicycle about one kilometer behind and they saw the whole scene,” he said.

In another incident in early May 2017, suspected soldiers killed a man with a physical disability and four other civilians in Mogiri, a town between Kansuk and Wudu. An elderly woman told researchers that her son, a SPLA veteran with a physical disability, had decided to stay behind in Mogiri when the rest of the family moved to Uganda. She said he was killed along with his two cousins and two other refugees who had returned to fetch food: “Soldiers shot him in the head. They then shot the two remaining ones. A friend from Mogiri found the bodies and came to inform us.”[60]

In another extremely violent incident in mid-May 2017, soldiers killed at least six men by locking them in a house and setting it on fire in Kudupi, a village to the southeast of Wudu.

Their relatives told Human Rights Watch that they had left a few weeks earlier to gather food and were about to return to the settlements. One of the two survivors of the attack described how soldiers forced eight men into a house, set it on fire, then shot at the men as they tried to escape, killing six of them – Samuel Ladu, Wanya Joseph, Malish Kenyi, Oliya, Ereku and Pitia:

They closed the door and locked it, set the house on fire and shot bullets through the walls. … Another guy and I managed to break out and escape. The others didn’t. Four were shot and two burned alive. When I returned the next day, I found the bodies and others joined me to bury them. We put five of them in a latrine pit and buried another separately.[61]

The elderly mother of one of the victims said: “It did not take 2 or 3 days before the Dinka came and attacked them. Now, my tears continue to fall because I think of my grandchildren. And at my age, it won’t take very long before I die.”[62]

Arbitrary Detentions, Torture and Enforced Disappearances

Human Rights Watch documented scores of cases in which soldiers arbitrarily arrested and detained civilians, including children, and subjected them to ill-treatment and torture. Researchers also identified several cases of enforced disappearances in which authorities denied detaining a relative or knowledge of their whereabouts or their fate.

Under international humanitarian law, anyone taken into custody during an armed conflict must be protected from “violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture” and “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment.”[63] International human rights law similarly prohibits torture, cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of a detainee in any circumstance.

Everyone deprived of liberty must be provided with adequate food, water, clothing, shelter, and medical attention. Detainees are entitled to judicial review of the legality of their detention, and all the rights to a fair trial, including the right to be tried and convicted for a criminal offense only by a court of law.

In all the cases Human Rights Watch documented, authorities did not provide these basic protections. In most cases, the victims were male civilians who lived in rebel-held areas or were suspected of links to the rebels.

A 32-year-old man from Wudu told researchers he was arrested by soldiers in February 2017 after he attempted to leave for Uganda with a colleague and his brother. He said soldiers stopped them on the road, surrounded them, beat and tied them, and took them to the Mundari barracks in Wudu where they were held in a cramped container with more for a week:

They said, “where are you going” and “why are you running?” and we explained that we were leaving because we were afraid. They slapped us, beat us. They wanted to shoot us but a commander said no. Then they put us in a container and accused us of being with IO. The container was full already of at least 20 people including soldiers, there was no food or water and we were not allowed to go the bathroom often enough. It was very hot and dry there, and very cramped.[64]

When he was finally released, following questioning by commander John Camillo, he returned to his home to find that everything had been looted. He then fled to Uganda.

In another example, a 49-year-old man from Kansuk said he was tortured in SPLA barracks in October 2016. He explained he was arrested with three other men in Kansuk following a nearby shootout and detained overnight in a poorly ventilated container that contained nothing but a jerry-can half full of urine:

Eventually they took me for interrogation that same night. They tied my elbows together in my back and it was very painful. I could feel my chest cracking in the front. Four soldiers took me inside a room. They asked questions like: “who shot the gun” or “who are the rebels”? …. The next morning, the paramount chief came to the barracks and told Peter Majok, the commander, that I was a good person, so they released me.[65]

In an extreme example of torture, a woman claimed soldiers had driven a nail into her brother’s head while in their custody. She told researchers how soldiers arrested her 35-year-old brother shortly before Christmas and tortured him. She saw him at the Mundari barracks. He has since disappeared.

“I went to see him at the barracks immediately after I heard of his arrest. They took him out of the container and he had blood coming down from his head because he had a nail in his skull. I saw blood coming down from his nose too,” she said. “The SPLA said he was taken to Juba but I don’t believe them. I think he died.”[66]

In some cases, relatives of a suspect are detained until the suspect surrenders, an illegal practice known as proxy detention. The 18-year-old son of a businessman who was suspected of operating in rebel areas told Human Rights Watch that soldiers had arrested him for a few days in June 2016 after his father escaped. “They arrested him to explain where his father was,” the young man’s grandfather told researchers.[67] “Soldiers badly caned him from 6 pm to 10 am and finally released him afterwards. We had to take him for treatment at the hospital.”

Two parents told researchers their children were taken into custody by soldiers in Wudu, and kept for a prolonged period in containers. In both cases, parents were extremely distraught because they had learned of information suggesting their children had been tortured or killed, and in one case authorities denied any information on the whereabouts or fate of the children. Human Rights Watch was not able to independently verify the allegations.

In the first example, a mother told researchers that in January 2017 four government soldiers came to her house around midnight to ask for money and arrested her husband and three sons, aged 15, 18 and 20. When she pleaded for their release, she was allowed to see her husband, who had been badly tortured on his genitals and who told her their sons were also badly tortured.

I went to the barracks in Wudu and soldiers asked me why I had come. I cried and the commander came out and ordered them to bring my husband. He was brought with his elbows tied in his back and a rope was going between his legs and tied to his testicles, which were all swollen. They had cut his shorts in the middle like a skirt. In local language, he told me that the children had been badly tortured during the night. Soldiers had taken spokes off a bicycle wheel and placed them in a fire and then they had inserted them in the hole of their penises.[68]

For the next three days, she returned to the barracks, asking to see her children but was never allowed to seem them. She eventually fled to Uganda with the rest of her family and does not know what happened to her husband and three children.

In the second case, a man who worked in Juba as a security guard claimed that three of his seven children, aged 10, 15 and 18, were arrested in Mere by soldiers in January 2017 and taken to the Mundari barracks in Wudu to be held in the container. The soldiers accused him of being a rebel and had arrested the children in his absence to compel him to surrender himself, he said. After hearing of the arrests, he travelled from Juba to Wudu to find them, but was not allowed to see them: “I went [to the barracks] for several days and was bringing food for them but I was not allowed to see them. They would tell me to leave the food there and go. Every day, Camillo [the commander] would say: “your children will be released tomorrow.”

He eventually found their bodies, dead, in the container: “At the end of January, a Kuku soldier told me that the three of them had died. When I heard the news, I went to see the county commissioner and together with him we went to the barracks. The commissioner ordered the soldiers to open the container and they did. There were three bodies inside and other people alive. My three children were lying dead at the end of the container. They were very thin because they had gotten no food.”[69]

Looting

Refugees from Kajo Keji told researchers that government troops often looted goods from homes and markets in the aftermath of skirmishes with the opposition, or as they conducted operations in towns or in the field.

After the attack on Kansuk, in June 2016, government forces extensively looted the market and houses and other structures vacated by civilians during the fighting. This included the Kabi Senior Secondary School, a boarding school where all of the mattresses, books and valuables where looted by soldiers in days following the opposition attack.[70] Other civilians from Kansuk told Human Rights Watch that their homes had been looted, including solar panels.[71]

Some people were also robbed by soldiers while trying to flee to Uganda. A 37-year-old father of seven from Jalemo told Human Rights Watch what occurred when he was stopped by two soldiers from the Bomure barracks as he rode his motorcycle towards Uganda in January:

They stopped me and said: “where are you going? Are you fleeing? Are you rejecting the government?” Then they took me by force into the bush and made me push the motorcycle to the side of the road. They wanted to throw me inside a ditch near the road but I refused to move. I was walking slowly, thinking ‘I am going to die’ and then they shot me. The bullet passed through my shoulder. They shot again but the gun refused to work. That is how I survived. When I came back to the road, they were gone with my motorcycle.[72]

Government forces and Dinka cattle-herders who went into Kajo Keji after most of the population left also stole cattle. In some cases, local cattle keepers were killed in the process.

An older man from Mogiri told researchers how armed Dinka cattle herders stole 500 head of cattle from him and six other older men who stayed behind to take care of the cattle after the village population fled to Uganda following the Mondikolok attack.[73]

Another farmer in his fifties said his 200 cows were stolen after Samson Kouyoubi, a 65-year-old man designated to take care of them, was killed by Dinka soldiers on the road between Mere and Juba in April.[74]

Pajok

With the conflict spreading into the Equatorias, the government’s attack on the town of Pajok, an Acholi town of roughly 50,000 in the newly created county of Ayaci (formerly part of Magwi county) in the former state of Eastern Equatoria, stands out as one of the largest-scale attacks on civilians. It also illustrates how the larger conflict plays on pre-existing local conflicts. In a May 15 memorandum that followed the April 3 attack, JMEC ceasefire monitors noted with concern that “the government appears to allow acts of violence by the security forces against its own people,” and the violence has “an ethnic dimension that results in mass displacement of citizens of a particular ethnicity.”[75]

Legacy of Tensions in Pajok

Community leaders told Human Rights Watch the April 3 attack took place in the context of pre-existing tensions between local Acholi clans. The Pajok clan, in control of an important trading and farming center in the Acholi-dominated territory east of the Nile, has long enjoyed economic and political advantages over the six other Acholi clans populating the area. Moreover, during the Sudanese civil war, Khartoum armed the Pajok to fight against other sections of the Acholi – notably the Panyikwara, Omero, Agoro, Palwar and neighboring Obbo who had joined the SPLA and with whom Pajok had land disputes. The Pajok garrison was eventually attacked by the SPLA in 1989, driving thousands of civilians to flee across the border to Uganda.[76]

After the new war broke out in 2013, these tensions resurfaced. Some Pajok community members joined Machar’s opposition, including Nathaniel Oyet, a former professor at Juba university who became a chair of the IO’s political mobilization committee and whom Machar appointed governor of the IO state of Imatong, in charge of the Pajok area in August 2015.[77] In addition, George Onek, a civilian educated in Uganda, became a brigadier for the opposition, recruited Acholi youth, and established a base about 10 kilometres to the northeast outside of Pajok town.[78]

Meanwhile, commanders from the other clans who had joined the IO defected back to the government in 2016 after President Kiir announced an amnesty for IO fighters in July.[79] Some local government leaders, including the Ayaci county commissioner – Benson Onek from the Obbo clan – and the SPLA division 6 commander at the time – Johnson Juma Okot from the Panyikwara clan – reportedly began to reference Pajok’s history of opposition to the SPLA and accuse its community of harboring the opposition.[80]

April 2017 Attack on Pajok

In late March 2017, roughly 1000 mostly Dinka soldiers from the SPLA Tiger division and a number of defected Acholi rebels now allied with the government, began to amass in Palawar, a few kilometers to the north of Pajok, under the command of Brigadier General Gildo Oling “Baranya”, an Acholi, and Col. Kurang Tarif Chuol, a Dinka.[81] Rumors began circulating that the soldiers would attack the small opposition base outside of town. Based on their experience from fighting between government and opposition forces on the Pajok-Juba road in October 2016, civilians thought the town itself would not be attacked.[82]

The attack began on April 3 when a large number of government soldiers entered Pajok from at least two different directions and began to shoot indiscriminately while also targeting civilians. Human Rights Watch was able to confirm that government soldiers that day killed at least 14 civilians, including 13 men and one woman. JMEC ceasefire monitors, CTSAMM, documented 16 killed.[83] The total toll could be much higher.[84] Most of the population fled the town at the time of the attack, and Pajok was subsequently extensively looted.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they heard gunshots coming that morning from the northeast quarter of the town, near the IO base. Minutes later, gunshots sounded from the north, along the road leading to the capital. Civilians realized they should flee.

“When I heard the bullets coming from all these directions, I knew that it was not a battle but an attack on civilians,” a local chief told Human Rights Watch. “I immediately called all of the 23 sub-clan chiefs to urge them to tell everyone to leave.” [85]

As people fled south to cross the Atebi river that flows east to west, an armored personnel carrier mounted with a loudspeaker drove down the main road towards the bridge. According to some witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, it broadcasted two separate messages. In Arabic, citizens were urged not to flee and to return to their homes. In Acholi, civilians were urged to flee along with their families. Human Rights Watch could not independently verify this claim, but the confusion could have led to more deaths. Many people told researchers they tried to return home and were shot or saw people shot.

Killings by Government Forces

Soldiers killed at least 14 civilians, often at close range. Witnesses who buried the bodies recounted the details of some:

Between a row of houses, we found the body of Ogeno Charles who had been shot in the abdomen. Then we went to find Amos Timothy who was under a tree, shot in the chest. Later we found Onen Long, a 20-year-old, who was killed in his outdoors shower space and had been covered with a blanket by his grandmother. On the third day, we found Okot James “Cirilaka”, who owned a phone repair shop and was shot outside his home. We also found Oriem Michael, who had mental problems and had been shot under a tree. There was also James Otoo, who also had mental problems, who we found after four days inside his home. There were many others but we did not bury them all.[86]

Others saw soldiers shooting people dead. A man in his 60s told Human Rights Watch he was returning home when he was intercepted in his car by the incoming soldiers along the main road, and saw them shoot a neighbor: “They pulled me out of the car and took my keys. Then, right in front of me, they shot at a man. His name was Opala Labite,” he recalled. After this, soldiers forced him to follow them and he saw others killed. “When we arrived in the center, under trees near the bridge, they shot Onen Long, who was a seller. Then they shot at Ogeno Charles, Amos Timothy and Lawrence Opiyo who were sitting together [….] Lawrence survived because he fell in a latrine when he ran. Ogeno was shot three times and died. Amos managed to run but they ran after him and killed him.”[87]

Soldiers killed at least three men with psychosocial disabilities. One of them was James Otoo, a 34-year-old who was staying with his mother when soldiers arrived in the morning. “They surrounded the compound and he refused to move. They shot him,” his mother told researchers. “He is dead. There is no way to know the names of those who killed him so I leave it in the hand of God.” she said.[88]

Another man said he watched from afar as soldiers shot his father, who was elderly and had a physical disability, in his house then set fire to the structure:

When I heard the gunshots around 8 a.m. on Monday, I was at home with my wife and my seven children. I took them to the bush, some three kilometers away from town, and then returned to Pajok to pick up my father because he could not walk. I carried him outside of the house, but bullets were flying all around us so we crouched down next to the road side to hide. My father said I should leave him to go protect my kids. He was feeling strong so I left him. He crawled back to his house, but soldiers came and asked him to come out. He took too long so they shot him and burned the house. I know that because I saw the scene from afar. […] In the evening, I found my dad’s charred body in the burned house.[89]

Ojok Peter, another man from Caigon neighborhood was found hanged after he had been badly wounded by gunshots. His brother-in-law recounted the incident: “The [soldiers] chased us and we split. They shot towards us and the brother to my wife, Ojok Peter, was injured in the leg. He could not move and they came towards him and took his phone and money and left him there. He was still alive,” he said. “His leg was broken by the bullet and so he crawled to a house to hide. When we returned many hours later, we found him hanged in the house.”[90]

Detention

Soldiers also rounded up some of the villagers and held them together under armed guard for several days. A 36-year-old father of seven said he was detained by soldiers who accused him and all Pajok civilians of being IO supporters and held him under a tree by the bridge. Along with a number of civilians left behind, he was guarded by soldiers for several days, until he escaped to Uganda. During that period, he and several others, some of whom were also interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch, were asked to help bury the bodies of those killed by government troops.[91]

Looting

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that government forces proceeded to extensively loot the town as the attack subsided. A community leader, who maintains links with the few civilians still in Pajok, told researchers that Acholi and Dinka soldiers broke into houses and looted all that there is. “The soldiers call Pajok ‘Dubai’ now because they can just loot all that they want.”[92]

A 55-year-old woman in communication with people who have remained in Pajok said she was told that all the houses had been looted: “They said that you could see that all the doors are opened. Even those who remain in Pajok cannot save our things because soldiers already took our things.”[93]

An elderly man who could not flee at the time of the attack and remained in Pajok for several weeks after the government troops came told researchers that soldiers stole three of his bicycles from his son’s house. “The day after the attack, commander Kurang called on the remaining people to meet with him near the bridge. He told us to organize small committees to report to him if his soldiers did anything wrong. But just as he was speaking to us, I received information that my house and that of my son were being looted,” he said. “When I got there, I found them breaking in and I tried to stop them but one of them said: ‘we’ll shoot you!’ Then they broke in and stole our belongings. Those who looted were Acholi so I reported, but the problem is the follow-up. The commander asked me: ‘can you identify those who did it?’ and I was afraid to reply because they have guns.”[94]

Many refugees interviewed by researchers as well as independent observers reported that soldiers made several trips with lorries to transport the looted goods to Magwi, north of Pajok.[95]

III. International Crimes and Accountability

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly documented the commission of war crimes and potential crimes against humanity in the current conflict in South Sudan, and emphasized the need to ensure the fair and effective investigation and prosecution of these crimes. The abuses documented in this report are no different, and many, if not all, can be classified as war crimes, and possibly as crimes against humanity, for which there needs to be accountability and justice for the victims.

Serious violations of the laws of war with criminal intent, acts such as purposefully making civilians the target of attacks as well as murder, cruel treatment and torture as described in this report may all constitute war crimes, and serious violations of human rights law that impose obligations to prosecute the perpetrators. Likewise, attacks directed against civilian property and humanitarian objects, pillage—the forcible taking of private property for non-military use, and the acts and threats of violence with the primary purpose to spread terror among the civilian population are all prohibited.

The government has consistently denied Human Rights Watch’s reporting of alleged crimes by its forces.[96] And while the government has repeatedly promised to investigate abuses, it has seldom done so.[97] Following killings in Wau in early and mid-2016, for example, it established commissions of inquiries into the violence and alleged abuses. However, no credible criminal investigations or trials took place there. The few soldiers accused of crimes against civilians continue to be tried in military courts, in violation of South Sudan’s own law.[98] Instead of being held accountable, several commanders involved in abuses have been promoted or shifted to other divisions.[99]

While justice is only one element of a larger framework of response, fair, credible trials for serious crimes can be instrumental to ending impunity and building respect for the rule of law. This can, in turn, help to minimize further crimes and promote durable peace. By contrast, lack of justice—including in the hopes of solidifying stability—has too often fueled further abuses in South Sudan and elsewhere.[100]

As national and international actors attempt to revitalize the ARCSS, there can be no bartering by the government of South Sudan or by the international community (including the UN Security Council and the African Union) on the requirement for accountability and justice. To this end there should be no amnesty for serious crimes committed in violation of international human rights and humanitarian law, and measures should be taken to ensure that no one bearing criminal responsibility for the worst crimes can escape prosecution by virtue of his or her position, rank or any form of official immunity.

The African Union took an unprecedented step in establishing a Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan, which detailed abuses committed in South Sudan, and supported the establishment of a criminal court to bring justice for the crimes.[101] The ARCSS peace agreement of August 2015 provided for the establishment of a Hybrid Court for South Sudan (HCSS), composed of judges, prosecutors and other staff from both South Sudan and other African states. The panels hearing cases are designed to include a majority of judges from African nations other than South Sudan.[102]

The court will have the authority to try genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other serious crimes that violate international law and Sudanese law committed since the current conflict began. It will be distinct from the national system and have primacy over South Sudan’s courts, and have authority over anyone accused of the crimes within its jurisdiction irrespective of rank or whether the accused is a government official.[103] These are critical elements for ensuring that investigation and prosecution is independent, impartial, and effective. Human Rights Watch research on the justice system in South Sudan underscored the system’s deep limitations, which would create major obstacles to fair, credible cases involving the most serious crimes.[104]

But more than eighteen months after the ARCSS provided for establishment of the HCSS, the AU had made little progress. On March 24, 2017, the AU Peace and Security Council notably called for the AU Commission "to scale-up ongoing efforts towards establishing the Hybrid Court of South Sudan.” [105]

The AU Commission had prepared a draft statute and other instruments to operationalize the HCSS. Further progress had been stalled, however, as South Sudan had yet to respond to AU Commission efforts to engage with the government on the substance of the court’s establishment.[106] While positive engagement with the government of South Sudan would help, the AU Commission has the authority to establish the Hybrid Court for South Sudan with, or without, the engagement of the government.[107]

On July 21, 2017, South Sudanese officials met with AU Commission and UN officials for discussions on the creation of the Hybrid Court for South Sudan in Juba. The meeting produced a joint roadmap for the court’s establishment, with finalization of the court’s statute and other legal instruments by August 31, 2017.[108] The conclusion of the roadmap is a potential breakthrough in advancing justice for grave crimes committed in South Sudan. The AU Commission and South Sudanese officials should now ensure continued momentum with full implementation of the roadmap.

In the meantime, the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan, established by the UN Human Rights Council, has an important role to play in collecting and preserving evidence for future criminal investigation and prosecution of serious crimes. The commission will need adequate financial and staffing support to implement this mandate, which was authorized by the council in March 2017.[109]

Some accountability can also be achieved by imposing further targeted sanctions on key individuals responsible for serious crimes. The UN Security Council should impose sanctions on such individuals but regional bodies such as the African Union and the European Union, as well as governments acting unilaterally, can also impose sanctions on those responsible. While key commanders such as the opposition’s James Koang, Peter Gadet and Simon Gatwech, and the government’s Santino Deng Wol, Marial Chanuong and Gabriel Jok Riek have already been sanctioned by the UN, other top military and civilian commanders should also be sanctioned.[110]

Based on evidence reported publicly since 2013, including in this and other Human Rights Watch reports, UN and NGO reports on serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law in South Sudan since the conflict started, Human Rights Watch submits that the following leaders should be among those subjected to targeted sanctions: President Salva Kiir, opposition leader Riek Machar, and former SPLA chief of staff Paul Malong Awan, who was appointed in April 2014 then replaced in May 2017. The individual criminal responsibility of these three men should also be the subject of investigation, all three being top commanders in position to give orders and with prima facie effective control over their forces which have been implicated in serious violations and abuses since the beginning of the conflict.[111] Other commanders who should be sanctioned include:

- Lt. Gen. Johnson Juma Okot, formerly in charge of the SPLA division 6 troops accused of abuses in the Equatorias and now Deputy Commander of Ground Forces.[112]

- Lt. Gen. Bol Akot, who was in charge of the Gudele and Mio Saba areas of Juba at the time of killings of Nuer civilians in December 2013, formerly in command of the SPLA commandos accused of abuses in Western Equatoria, currently director of the South Sudan National Police Service;[113]

- Lt. Gen. Marial Nour Jok, head of the SPLA Military Intelligence since April 2014, who is the superior of officers accused of arbitrary detentions, torture and enforced disappearances in the Equatorias and Wau regions;[114]

- Lt. Gen. Attayib “Taitai” Gatluak, formerly head of SPLA Division 4 accused of abuses in the Unity region in 2015, and now in charge of the SPLA Division 5, accused of abuses in Wau late 2015;[115]

- Gen. Johnson Olony, an opposition commander accused of forced recruitment of fighters, including children, in the Upper Nile region;[116]

- Maj. Gen. Matthew Puljang, who commanded forces accused of abuses in the Unity region in 2015 and forcefully recruited children.[117]

The potential criminal responsibility of those listed above, both direct and on the basis of command responsibility, should also be the subject of criminal investigations, with a view to prosecute those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity in fair and credible trials.

If a credible, fair and independent hybrid court is not established, the option of the International Criminal Court (ICC) remains and should be pursued. As South Sudan is not a party to the court, the UN Security Council would need to refer the situation to the ICC in the absence of a request from the government of South Sudan. The council has to date failed to effectively support referrals it has made involving the situations in Darfur, Sudan and Libya and needs to increase support to situations it refers to the ICC.[118]

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Jonathan Pedneault, researcher for the Africa division, based on research conducted in Uganda with Jehanne Henry, senior researcher, Africa division. The report was edited by Jehanne Henry and was reviewed by Elise Keppler, associate director for the International Justice division; Akshaya Kumar, deputy United Nations advocacy director; Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor; and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director. Savannah Tryens-Fernandes, associate with the Africa division, assisted with the timeline and provided editorial assistance. Olivia Hunter, publications and photography associate, Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, and Jose Martinez, senior coordinator, provided production assistance. John Emerson produced the maps.

Human Rights Watch gratefully acknowledges the victims, witnesses, family members and friends of victims who spoke with us, sometimes at great personal risk.