Nations in Transit 2012 - Bosnia and Herzegovina

| Publisher | Freedom House |

| Publication Date | 6 June 2012 |

| Cite as | Freedom House, Nations in Transit 2012 - Bosnia and Herzegovina, 6 June 2012, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4fd5dd32c.html [accessed 8 October 2022] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Capital: Sarajevo

Population: 3.8 million

GNI/capita, PPP: US$8,910

Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2010.

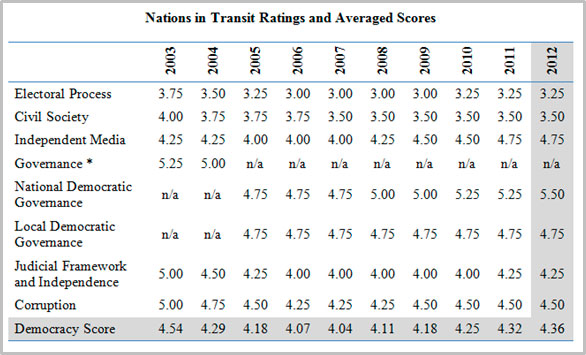

* Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance, to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects.

2012 Scores

| Democracy Score: | 4.36 |

|---|---|

| Regime Classification: | Transitional Government or Hybrid Regime |

| National Democratic Governance: | 5.50 |

| Electoral Process: | 3.25 |

| Civil Society: | 3.50 |

| Independent Media: | 4.75 |

| Local Democratic Governance: | 4.75 |

| Judicial Framework and Independence: | 4.25 |

| Corruption: | 4.50 |

NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year.

Executive Summary:

On December 28, 2011, leaders of six main parties in the two-entity federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) announced their intention to form a state government, which the Parliamentary Assembly confirmed in February 2012. This end-of-year compromise was preceded by 14 months of political deadlock and reform paralysis following the October 2010 elections. As a result, 2011 was, in many ways, a "lost year" for BiH, during which no key democratic reforms took place, and no progress was made on the path to European Union (EU) and NATO membership.

Political elites in BiH's two entities – the Republika Srpska (RS) and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) – continue to lack a shared vision for the country and a consensus on the political system established under the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords (DPA). RS nationalist rhetoric and resistance to state (i.e. all-BiH) level institutions became more strident in 2011, deepening BiH and FBiH anxieties about RS plans to secede from the state of BiH.

In the absence of trust between the RS and FBiH entity leaderships, the stability and integrity of BiH continues to rely on the presence of international actors, mainly the Office of the High Representative (OHR) established by the DPA, which ended the war in 1995 and effectively divided the country in half. Under these circumstances, BiH has achieved neither the cohesiveness nor the capacity to act as a stable and sovereign state. The country remains under the international supervision of the OHR, the highest authority responsible for the civilian implementation of the DPA, and is still under threat of dissolution.[1]

Reform priorities to secure BiH's advancement towards EU integration in tandem with the rest of the region were not met in 2011. The year saw no credible effort to address the 2009 ruling of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in the "Sjedic-Finci" case on electoral discrimination, and long-awaited state aid and census laws remained pending. These and other important issues were blocked by the lack of agreement to form a state-level government until the end of the year.

According to security analysis by two non-profit organizations in October 2011, police were subjected to increasing political pressure "to relinquish their relatively new operational autonomy and to submit to ethnic political loyalties."[2] At the same time, EU Military Force (EUFOR) troop strength was reduced to some 1,300 personnel. Though EUFOR can deploy over-the-horizon reserves to buttress troops on the ground, analysts claim it is no longer a credible conflict deterrent.[3]

National Democratic Governance. The year saw a destructive and divisive political dynamic that paralyzed state-level governance. Leaders did not agree to form a government until year's end, and BiH's EU reform agenda stalled. The RS challenged the legitimacy of state institutions and the international presence in BiH. The EU intervened to prevent an RS referendum questioning BiH's constitutional order under the DPA. Due to this dysfunction, division, and stagnation, BiH's national democratic governance rating declines from 5.25 to 5.50.

Electoral process. Bosnia's electoral legal framework did not change in 2011. Legislators did not address the 2009 ECHR ruling in the Sjedic-Finci case by amending legislation to eliminate ethnic-based discrimination in electoral processes. The state parliament began amendments to three election-related laws, but none were proposed or adopted. As the year saw no significant developments in the electoral field, the electoral process rating remains 3.25.

Civil Society. Despite the strong performance of some civic groups in 2011, BiH's civil society remains immature and dependent on international funding. Most civic groups do not have strong voices on key social issues such as unemployment and economic policy. Religious organizations have begun to seek more influence, with some results, especially in education. As most civil society organizations remain relatively weak in terms of impact and independent financial sustainability, BiH's civil society rating remains 3.50.

Independent Media. Partisan editorial policies among media outlets and political pressure on the press endure, undermining public trust in the media as a reliable source of information and in the democratization process in general. Many media outlets struggle to find sustainable financing while remaining independent. Political pressure on the Communications Regulatory Agency intensified in 2011. With no observed improvements in the media landscape in 2011, BiH's media independence rating remains at 4.75.

Local Democratic Governance. Municipalities remain financially dependent on higher levels of government, and coordination between state, entity, and local governments remains weak, despite nascent efforts to improve cooperation. Key legislation related to decentralization and local self-governance is not being properly implemented. Municipal budgetary procedures are opaque, and the overall transparency of municipal governments needs improvement. BiH's local democratic governance rating remains 4.75.

Judicial Framework and Independence. BiH made scant progress on judicial reform in 2011. The judiciary is inefficient, with a sizeable case backlog. It is not fully independent, and political attacks on the courts intensified in 2011. The RS challenged the very legitimacy of state courts. In June, BiH leaders began a dialogue on judicial reform with the EU. Due to weak progress on judicial reform and political entanglement in the judiciary, BiH's judicial framework and independence rating remains at 4.25.

Corruption. No progress was made in combatting pervasive corruption during the year. Existing anticorruption legislation is unevenly and unreliably implemented. A key anticorruption government body created in 2009 is still defunct as the government drags its feet on appointments and resource allocation. Media coverage of graft and misconduct was weak throughout the year. Due to BiH's poor record on corruption and the lack of political will to tackle the issue, its corruption rating remains unchanged at 4.50.

Outlook for 2012. Governance in BiH is likely to remain paralyzed by the enduring conflict between the two entities, which still do not share a mutual understanding on the direction and future of BiH. The decision to form a government at the state level does not mean the ruling parties in the two opposing blocks will secure a stable parliamentary majority for the swift and smooth adoption of key legislation, including reforms emphasized by the EU.

With other Balkan countries advancing towards the EU, BiH's weak progress on EU reforms may lead the international community to think BiH leaders are not committed to meeting EU accession criteria, for instance on electoral policy. Given the recent spike in nationalist rhetoric and incidents of interethnic violence, BiH leaders could shift focus towards domestic security, rather than the EU enlargement process, which would undermine even the long-term prospects for democratization in BiH.

National Democratic Governance:

Under the Dayton system of post-conflict power sharing, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has neither the cohesiveness nor the agency of a unified sovereign state. BiH operates under international supervision as a loose, asymmetrical federation of autonomous entities: the centralized, Serb-dominated Republika Srpska (RS), the decentralized, Bosniak and Croat-dominated Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), and Brčko, a district with its own governing institutions. At the state level, BiH has a tripartite presidency with one Bosniak representative, one Serb, and one Croat. This structure was introduced by the Dayton Peace Accords (DPA) in 1995 as a temporary measure to end a war. Sixteen years later, BiH remains dependent on international involvement, especially the Office of the High Representative (OHR), which is responsible for the civilian implementation of the DPA and the EU Delegation to BiH which guides the European integration process on the ground.[4] Throughout 2011, BiH existed without a central government amidst infighting that paralyzed state governance and blocked state-level legislation required to prepare BiH for European Union (EU) accession.

The current governance impasse stems from personal animosities and longstanding ideological differences between the entities over the purview of BiH governing structures and the future of BiH as a state. RS leadership views state institutions as joint, treating the state as a confederation of two sovereign entities. Bosniak leaders in the FBiH, however, see BiH as a sovereign state with its own autonomous rights. The position of the Bosnian Croats is divided along party lines and fluctuates: the two HDZ parties (Croat Democratic Union of BiH and Croat Democratic Union 1990) sided more with the RS leadership's ruling Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD) in 2011; while the Croat Party of Justice (HSP BiH) and the People's Party Work for Betterment (NSRB) sided with the FBiH ruling parties, the Social Democratic Party (SDP BiH) and Party of Democratic Action (SDA). Throughout 2011, RS leaders treated all statewide, BiH-level reforms as efforts to weaken the autonomy of the RS and strengthen the central powers of the BiH, with the ultimate aim of abolishing the RS entity. RS authorities openly and more frequently called for the dissolution of the state, refuting the legitimacy of the BiH Constitutional Court and other state level institutions. Meanwhile, FBiH leaders viewed RS resistance to state institutions and state-level reforms as part of a strategy to weaken BiH while creating the preconditions for a functional, independent, RS state. Immobilized by mistrust, the two sides found compromise nearly impossible, refusing to negotiate without continuous international reassurances that neither scenario would occur.

Inability to agree on a list of programs to be financed from EU aid very nearly cost BiH €96 million from the EU Instrument of Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) fund in September. The original deal signed between Brussels and Sarajevo in February allocated €8.2 million of the funding to agriculture, employment, statistics, and the judiciary. When RS leaders declared that these sectors should be managed at the entity level, the Council of Ministers of BiH (CoM) revised the IPA program for 2011 to exclude the disputed projects, reducing the overall allocation from roughly €96 million to €88 million. After the FBiH government objected to the loss of funding earmarked for state-building efforts, the EU suspended the aid in September and threatened to reallocate the €96 million from the IPA to regional projects. Ultimately, Zlatko Lagumdzija, the leader of FBiH's dominant party SDP BiH and RS President Milorad Dodik negotiated an agreement on how the contested €8.2 million would be spent.[5] The EU restored the funding in October but called for a more effective EU coordination mechanism within the different levels of government in BiH.[6]

The government took no concrete steps in 2011 to address a 2009 decision of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in the Sejdic-Finci case, which ruled that Jews and Roma could not be excluded from running for the BiH presidency or House of Peoples, the upper chamber of the BiH Parliamentary Assembly. Constitutional provisions prohibiting BiH citizens that do not belong to the three constituent peoples (Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks) from being elected to these bodies remained in the BiH constitution and electoral law. Resolution of this issue is one of the two main conditions for enforcing the BiH Stabilizations and Association Agreement (SAA), a key step in the accession process. The Interim Agreement has been in place since 2008, but the SAA, ratified by all EU members, will remain unenforced until the conditions are met. In September, both houses of the Parliamentary Assembly adopted a decision to form a working group for addressing the ECHR ruling, but it did not formulate amendments to the Constitution and the Election Law to meet the EU's condition.

The other EU condition for the SAA ratification was the adoption and implementation of a long-delayed central government State Aid Law, the draft of which was still in parliamentary procedure at year's end. Having agreed on at least one of the draft law's central principles – the distribution of ministerial seats in the new Council of Ministers of BiH – the leaders of the ruling parties also agreed to adopt a set of similarly "EU-required" laws, including the Census Law. The EU insists that collection of accurate, statistical data through a census is a pre-condition for any sound economic policy plan, distribution of EU funds, or even an attempt to answer the EC questionnaire after BiH formally applies for EU candidate status. The ruling parties came close to an agreement on this law, but it was put into a package with other EU laws that legislators were to address during the formation of a government and thus fell hostage to the political stalemate. The census remains a sensitive issue because it will plainly reflect the demographic consequences of the war in each entity and may affect the formation of future governments in each entity, which were originally based on the population census of 1991. However, none of the EU-required laws were passed in 2011. The five objectives and two conditions necessary for the closure of the OHR were also not completed because of the stalemate.

In the FBiH, the efforts of the main Croat parties to form a third, Croat entity in BiH stirred discordant rhetoric. In April, two Bosnian Croat parties, HDZ BiH and its splinter HDZ 1990, organized a Croat National Assembly in Mostar, where they called for a Croat majority federal unit to be formed through constitutional changes in BiH. The two HDZs also considered illegal the FBiH government, formed in March through a coalition agreement. They objected to the decision of the SDP, which won the 2010 general election, to form a government with the other two Croat parties, the NSRB and HSP, rather than the HDZs, which had ruled in the name of the Bosnian Croats since the first multiparty elections in BiH, in 1990. On the initiative of the HDZs, the Croat People's Assembly, comprising all municipalities and Cantons with a Croat majority, convened in Mostar in September. Leaders were instructed to contest decisions by the "illegal and unconstitutional FBiH Government."[7]

The year also saw a legal crisis. On 13 April, the RS National Assembly (RSNA) held a special session to discuss the role and activities of the High Representative (HR) of the international community in BiH and the establishment, jurisdiction, and practice of state-level judicial institutions in BiH. The RSNA ended up adopting five sets of conclusions. Some of them directly challenged the role of the HR and his powers as defined under Annex 10 of the General Framework Agreement for Peace (GFAP) within the DPA, as well as all decisions and laws enacted by the HR pursuant to his mandate. Others rejected the authority of the Constitutional Court of BiH, a pillar of its constitutional order under Annex 4 of the GFAP.[8]

At the same session, the RS leadership decided to hold a referendum in June to challenge the international supervision of the peace process and the legitimacy of state institutions on RS soil. Brussels intervened in May, when Catherine Ashton, the EU foreign policy chief, flew to the administrative center of the RS in Banja Luka to meet with the RS President Dodik, who agreed not to hold the referendum. The visit came a day after the EU issued a deadline to Dodik to call off the vote or face personal sanctions, including the freezing of his assets and a ban on travel to the EU. After meeting with Ashton, Dodik said the referendum was "unnecessary for now" because the EU had agreed to open a "dialogue" on the judiciary.[9]

The OHR considered the results of RS's special session a serious violation of the peace agreement because they directly challenged two annexes of the GFAP. The OHR said the conclusions sought to undermine the very constitutional order of BiH and noted that these decisions must be seen in a broader context, as the "authorities of Republika Srpska and in particular its President, have continued openly to question the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina, repeatedly questioning the sustainability of the country and advocating its dissolution."[10]

One political crisis followed the other while the economic situation worsened in BiH. For example, the RS Pension and Disability Fund has been relying on short-term loans from commercial banks to maintain payments. Opposition parties opposed taking additional loans to finance various projects considering that the RS had a cumulative debt of 3.56 billion KM (€1.78 billion).[11] Economists also warned against the RS government borrowing from commercial banks and issuing bonds with high interest rates to cover the deficit.[12] In September, Mladen Ivanic, an economics professor and RS political leader, said "the RS is facing the Greek scenario if it continues to take more loans."[13] Serbian Democratic Party (SDS) President Mladen Bosic warned that the RS isn't under existential threat from Sarajevo or the international community, but from the economic policies of its own government.[14]

The FBiH, meanwhile, struggled to pay a debt to the RS related to the distribution of Value Added Tax (VAT) revenues. The Steering Board of the Indirect Taxation Authority (ITA) decided in September that the FBiH would settle its 33.8 million BAM ($23 million) debt to the RS within three months. However, it was unpaid at year's end.

The stability of the country and the region continued to rely on a meaningful international presence. The divisive rhetoric of the political elite trickled down per usual. Nationalist rhetoric inspired violent incidents at football stadiums between Serbs and Bosniaks in Banja Luka and between Croats and Bosniaks in Mostar. The renewed ethnic dimension to football hooliganism reminded citizens of similar incidents at sporting events before the wars related to the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[15]

In this context, the international community concluded that the mandate of the High Representative remains crucial for securing the stability of the state. At the same time, the EU reinforced its office in Sarajevo, merging the EU Delegation with the Office of the EU Special Representative with the mandate to politically facilitate the EU integration process of the country and support BiH on its path to accession. However, progress remains modest. Though political representatives of the three dominant ethnic groups verbally support the BiH's EU ambitions, some evidently believe different paths to membership are possible, including outside the BiH institutional framework. This led EU representatives to continuously repeat that BiH can join only as a single, unified state.[16]

Electoral Process:

The last general elections in Bosnia-Herzegovina were held October 3, 2010 and were entirely administered by local authorities. There were no elections in 2011. Municipal elections will be held in October 2012. "A credible effort," according to the EU, is needed to address the 2009 ECHR ruling by adjusting electoral rules to end ethnic-based discrimination in the electoral process. Currently, citizens who do not identify themselves as Bosniak, Croat, or Serb cannot run for the presidency of BiH. RS voters may only vote for a Serb member of the BiH presidency, while voters in the FBiH may only vote for either a Bosniak or Croat candidate. Likewise, a Serb registered in the FBiH or a Bosniak or Croat registered in the RS cannot run for the BiH presidency. The same restrictions apply to the House of Peoples. In December 2009, the ECHR issued a legally binding decision that ethnicity-based ineligibility is "incompatible with the general principles of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms."[17] BiH authorities failed to address the issue in 2011.

The BiH Parliamentary Assembly began the process of amending the Election Law, the Law on Political Party Financing, and the Law on Conflict of Interest. The lower chamber adopted a conclusion on forming a working group to manage the proposals. The most important proposed change dealt with the Election Law and the introduction of closed election lists. In September Transparency International BIH (TI BiH) supported the planned amendments, but emphasized that changes to legal provisions on party lists, party financing, pre-election campaigns, and conflict of interest should be done in consultation with civic groups to ensure transparency and accountability.

TI BiH noted significant room for improvement on electoral legislation to harmonize laws with international best practices. It said the law on conflict of interest should clearly define which situations qualify as conflicts of interest in order to narrow the space for political influence on institutions responsible for the law's implementation. A clear definition would also enable citizens and NGOs to initiate proceedings in cases of conflict of interest and to be a party in these cases.[18] TI BiH opposed closed party lists, which it said prevents democratization within the parties and gives even greater control to party leaders while breaking the link of accountability between elected officials and their electorates.

The parliamentary working group met throughout the year, but no amendments were formulated or submitted to the Parliamentary Assembly in 2011. If submitted in the first three months of 2012, the changes will affect the October municipal elections.

Civil Society:

Civil society organizations in BiH have acquired neither the social status nor the financial self-sufficiency to play a major role in public life. The funding provided to Bosnia's nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) by the international community was intended to foster indigenous and community-based peacebuilding endeavors, but NGOs have become wholly dependent on foreign funding. A few organizations, including Transparency International BiH and the Center for Civic Initiatives, managed to influence the government and to raise awareness of critical issues such as corruption, political transparency, and accountability in society. A few others made their voices heard and shared their expertise in public debates, but they remain over-dependent on funding from international donors. Because of the weak economy in BiH, domestic fundraising is nearly impossible.

In general, government officials at all levels remain unreceptive to policy advocacy, except when pressured by domestic media, which happens mostly when the interests of the media owners correlate with public interests. Public policy research groups continue to be largely ignored, and the government rarely consults NGOs over policy-making decisions. Important laws are rarely subject to public debate, which are also not very open to input from civil society groups. Meanwhile, some civil society organizations undermined their own credibility by aligning with political parties.[19] This was particularly evident in the months before and after the October 2010 parliamentary elections. At the same time, some NGOs lost momentum after the elections ended without the establishment of a central government.

In contrast to other civil society organizations, religious groups are increasingly vocal and influential. Their demands sometimes conflict with the reform needs of public institutions, including the education system, which suffers from polarization and perpetual financial crisis. In April, the newly appointed SDP BIH minister of education of the Sarajevo Cantonal government, Emir Suljagić, attempted to redress grade point average (GPA) inflation for students subscribing to majority religions by removing marks earned for Religious Education classes from students' GPAs.[20] The decision outraged leaders of the three dominant religious communities in BiH (Islamic, Orthodox and Catholic), who felt it was calculated to re-incentivize religious education. Mustafa Cerić, head of the Islamic community in BiH, publicly warned Minister Suljagić he would face a "Sarajevo Spring" inspired by the recent uprisings in countries in the Middle East and North Africa, if he did not withdraw the decision.[21]

Numerous NGOs and other members of civil society, including the PEN association of writers, reacted to what they qualified as hate speech by Cerić at the religious gathering in Herzegovina during which he attacked the decision and Minister Suljagić. However, the minister's party soon surrendered to the pressure of the Islamic community as well as its coalition partner SDA and withdrew the regulation. A culture and religion subject was introduced as an alternative to religious instruction in May, financed from the already overstretched cantonal budget.

Many primary and secondary schools across the country separate their students according to language, or according to a curriculum which is designed for a particular national group (so that students follow different school textbooks, some of which offer directly opposing information). This practice most visibly manifests itself in the existence of mono-ethnic schools and the existence of "two-schools-under-one-roof" in many districts. In the latter, children of different national groups study in the same building but are segregated into different school shifts based on the above criteria. In schools offering only one curriculum, provided that there is a sufficient demand, students of a minority constitutive national group have the legal right to request to study their own "national group of subjects" (mother tongue, history, geography, music), separately from other students.

Higher education continues to suffer from corruption, outdated curricula, and a lack of sufficient action on reforms required by the Bologna Process, which aims to create a European Higher Education Area with high standards of education and academic exchange among European students and professors. In higher education, integration, de-politicization, and reform are still much needed.

In August, the Riaset of the Islamic community in BiH presented the findings of a report that, among other things, identifies by name all the alleged Islamphobes in government, media, and civil society. Some civic groups heavily criticized the document for publicly branding those among their ranks who had spoken out against certain actions of BiH's Islamic community and its leadership.[22]

Independent Media:

A complex post-Dayton political structure, the slow post-war recovery, and lack of economic development have determined the development of media in BiH. BiH has a diverse and complex media landscape, with some 200 broadcasters and 100 print media outlets, most of them private; the three dominant public broadcasters are BH RTV (State radio and television), RTRS (RS RTV) and F RTV (FBiH RTV). Media remained free in legal terms, but editorial policy continued to be influenced by the ownership structure and affiliations with political parties. Media such as the ATV and Buka portal in Banja Luka, TV Hayat in Sarajevo, and some weeklies have escaped direct political influence, but resisting political affiliations has strained their finances. Media in general remain financially vulnerable and prone to political influence in a continuously shrinking advertising market.

International financial support played a strong role in BiH's transition from publicly-owned to market-driven media. The objective of this assistance was the creation of independent media capable of moderating the nationalist voices behind past conflicts in BiH. International funds were used to create new media outlets such as the Open Broadcast Network (OBN) and to support independent media established during the war (such as Banja Luka-based Nezavisne novine) or immediately thereafter (like Banja Luka-based Reporter magazine). The effort was not self-sustaining, however. The OBN has not developed into an influential broadcaster; after the international financing stopped, it went commercial and began airing reality television programming, rather than substantive news or entertainment. Most print media failed to remain impartial. The public perceives the media as partisan and lacking credibility.

By 2002, the international agencies and donors that had been key backers[23] of BiH's media development had begun to withdraw their support. In a weak, politicized economy with limited advertising opportunities, pressure grew from local elites to reverse the dynamic of media professionalization and independence. As former opposition parties like the Social Democratic Party BiH and the Alliance of Social Democrats came to power, the media that had supported them in opposition struggled to remain objective.[24]

Long overdue reforms of the public broadcasting system – a key issue in EU accession negotiations – made no progress in 2011, hampered chiefly by nationalist elites struggling to maintain control over the public broadcasters in their constituencies.[25] Launched in 2002, reforms were intended to create an integrated system with public broadcasters overseen by a single corporation, striving for balanced and objective reporting. The changes were also meant to include a joint newsroom shared by all three public broadcasters in BiH. However, due to a lack of political support for a unified system, cooperation among the public broadcasters remained poor. BiH's main telecommunications and electronic media regulatory body, the Communications Regulatory Agency (CRA), has not had a director-general since 2007. In 2011, parliament ordered the agency to appoint an SDS official to the directorship, despite provisions in the Law on Communications that require the selection of the director to be merit-based and apolitical.[26]

Regional press lack independent editorial policy and sufficient resources for quality production. The media landscape may improve, however, with the launch of Al Jazeera Balkans, which began broadcasting news and current affairs programming to audiences across the Balkans in regional languages in late 2011. The channel is available on most major cable services and via satellite. Based in Sarajevo, the team is made up of regional staff. In its first two months of operation, Al Jazeera Balkans emphasized its commitment to independence and professionalizing news production in the region. The station also provides a documentary program that attempts to tackle cultural and ethnic prejudices.

Internet penetration reached 55 percent in 2011, up from 52 percent in 2010. According to CRA statistics, the number of internet users in BiH has doubled since 2007.[27] As of June 2011, 1.1 million BiH residents were members of the social-networking site Facebook.[28] The government did not attempt to restrict internet use in 2011.

Local Democratic Governance:

The status and rights of local self-government (LSG) as guaranteed by the European Charter on Local Self-Government were secured by the High Representative's Decision on the 2004 reorganization of the City of Mostar and its incorporation in the FBiH constitution. These statutes protect the right to local self-government and are a powerful tool for many local government units in BiH to challenge FBiH or cantonal legislation before the FBiH Constitutional Court.

Though municipalities can draft and implement policy in every area except elementary education and the use of natural resources, they are not financially independent of the higher levels of government. The RS government must approve every loan undertaken by a municipality, as well as European Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) funds. (The rules are more flexible in the FBiH). Municipal tax regulation remains murky, and there is no law on LSG financing. The 10 cantons in FBiH control the majority of public financing sources for the Federation's 79 municipalities; the RS entity controls finances in the Serb-dominated area of BiH. During the political crisis, however, the higher levels of government did not share budgetary funds from The World Bank and the IMF with the municipalities.

Implementation of LSG legislation is weak. Passed in 2006, the FBiH Law on the Principles of Local Self-Government is a systematic framework that requires cantons to transfer certain duties and the related finances to the municipalities. The law foresees the creation of numerous laws at the entity and cantonal levels, but very few have been adopted.

When disputes arise between the municipalities and the Canton or the FBiH entity, local authorities have the right to appeal to the FBiH Constitutional Court, which they did frequently in 2011. This hampers municipal reform and the functioning of the different levels of government. The Sarajevo Canton has been particularly problematic. In October 2010 the FBiH Constitutional Court ruled that the Sarajevo Canton had violated the right to local self-governance in the Sarajevo Center Municipality. It had apparently failed to harmonize provisions in the relevant cantonal legislation with those in the Law on Principles of LSG, among other shortcomings. The dynamic between the strata of government in BiH is expected to be a significant issue in the 2012 election campaign.

The FBiH is trying to improve inter-governmental coordination. In October, FBiH Prime Minister Nermin Nikšić signed an agreement with the Association of Municipalities and Cities of the FBiH intended to ensure closer cooperation and institutionalized dialogue on improving both LSG and the decentralization process in accordance with the Law on the Principles of LSG.[29] Under the agreement, a code of relations was drafted to improve coordination between different levels of government in FBIH, which are charged with implementing the Law on the Principles of LSG and cooperating on issues related to LSG property and the use of natural resources. The FBiH government indicated a readiness to discuss relations between the local, cantonal, and federal levels and the division of responsibilities.

In 2011 the RS also drafted a code to coordinate relations between entity and local governments. However, the Association of Towns and Municipalities of the RS was less focused than its federation counterpart. LSG experts said it was trying to avoid conflict with entity authorities that oppose further autonomy for the municipalities.

Under domestic law, citizens have the right of direct participation in local policy-making processes – through public hearings and other means – but public participation hinges largely on the strength of the NGO sector in each municipality. For example, in municipalities where civic groups are strong and local authorities are receptive to their initiatives, public debates are held regularly; in districts where such groups are weaker, public debates are not held at all.

Media rarely cover local issues. In general, the mainstream press ignores developments at the local level, which are covered only in municipalities with their own radio stations and other media outlets.

Transparency in local governments remains problematic. While existing legislation grants freedom to information, not all municipalities publish their budget drafts online, and budget documents are not easily available to citizens. Under law, municipal governments do not have to publish so-called citizens budgets (short, clear summaries of government spending) or Web sites.[30] Media rarely cover local issues. In general, the mainstream press ignores developments at the local level, which are covered only in municipalities with their own radio stations and other media outlets.

Accountability has nevertheless improved significantly since the introduction of direct mayoral elections: in 1999 in the RS and 2004 in the FBiH, respectively. Mayors are usually more accountable to the citizenry than Municipal Council members, who remain under the strong influence of political party presidents and dependent on funding from the higher levels of government. Municipal administration is often more competent than at the higher levels of government, where the personnel turnover is higher because of staff changes after national elections.

As regards representation, participation of women in LSG institutions matches the higher levels of government. Ethnic minorities remain less represented in local government because the principle of equal proportionality in representation of constituent people in governing structures is better implemented at the higher levels of government.

The Brčko District remained under international supervision throughout 2010, ensuring that its institutions continued to function effectively. The High Representative (HR) issued decisions in September 2009 concerning the technical steps needed to complete the Brčko Final Award and resolve its status, but the RS government and National Assembly adopted measures that nullified those decisions.

Judicial Framework and Independence:

BiH has four separate judicial systems (state-level, RS, FBiH, and Brčko District) with no single body authorized to guarantee uniform application of the law. The judicial system is overly complex and inefficient as a result. Legislation and judicial practice differ between the two entities. The judicial system is not fully independent, and political pressure and verbal attacks against the judiciary intensified during the year.

In its 2011 Progress Report, the European Commission (EC) noted that "attempt [s] to undermine the independence of the judicial system remains an issue of serious concern."[31] Further undermining the independence of the judiciary, the budgetary procedures and competences of the 14 responsible authorities still need to be harmonized and narrowed. The EC noted little progress on judicial reform in the Progress Report.

The April RSNA special session had significant implications for the judiciary. The conclusions reached rejected the authority of the BiH Constitutional Court and that of all state-level judicial institutions on RS territory. In May RS President Dodik agreed to cancel a referendum on state courts and the international presence in exchange for negotiations with the EU on the judiciary, a key institution-building priority on BiH's path to European integration. The so-called Structured Dialogue on Justice began in June as a platform for BiH authorities to discuss reforms and legislative changes in line with European standards to ensure an independent and accountable judicial system to the benefit of every citizen. In the past, Dodik said Muslim judges should not preside over cases in the RS because of the threat of bias.

At the first dialogue meeting, the EU asked a set of technical questions. BiH authorities submitted answers in August, and, following a review by Brussels, a second meeting was held on November 10-11. No major achievements were made, revealing the gulf between the two entities on the state judiciary. The dialogue continued in 2012 and is envisioned as a long-term process.

In September, the FBiH House of Representatives adopted draft amendments to the FBiH Penal Code to criminalize genocide denial. Though the provision was not adopted in 2011, if it becomes law persons found guilty of genocide denial could face prison sentences ranging from three months to three years.

Throughout the year, RS authorities criticized the effectiveness and legitimacy of the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council (HJPC), the BiH body responsible for the independence and professionalism of judicial institutions. As over 2 million pending cases are in the courts, HJPC President Milorad Novakovic publicly called legitimate the criticism that the BiH judicial system is inefficient. In September, Novakovic emphasized, however, that the HJPC has a legal mandate and ensures the independence of the judicial system to guarantee that "there is no return to the times when MPs were electing judges and prosecutors."[32]

The HJPC created a special unit to redress inefficiency in the judiciary. It also adopted measures to reduce the backlog of pending cases, most of which concern unpaid utility bills. The backlog fell slightly, but the HJPC could not fill many newly created posts, including judgeships, to combat inefficiency due to funding constraints. State courts continued to process war crimes cases, with modest progress on reducing the attendant backlogs. However, lower courts had less success, according to the EC.[33]

Serb and Croat representatives in the BiH House of Peoples refused to adopt a report on the work of the BiH Prosecutor's Office for 2010. They objected to the role of foreign prosecutors and judges and the international community's influence on the BiH judiciary. They also questioned the legality of the Prosecutor's Office, rhetoric that many observers saw as a form of political pressure.

Corruption:

Little was achieved in the fight against corruption in 2011. Graft and misconduct remain widespread, posing major impediments to political and economic development. The existing anticorruption strategy has not been implemented, and political will to tackle misconduct is weak. The year saw no high profile anticorruption cases. Bosnia ranked 91 of 183 countries in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions index 2011. In the former Yugoslavia, only Kosovo had a worse rating.[34]

Public opinion surveys show that that Bosnians believe corruption is worst in education and healthcare. Over 60 percent of respondents to a July survey said the healthcare sector, where informal payments are commonplace, is corrupt.[35] Civic groups have launched advocacy campaigns on anti-corruption efforts, the linchpin of which is the government's 2009-14 anti-corruption strategy and action plan. In 2011, the Center for Civic Initiatives distributed informational pamphlets and badges with the mantra "I do not give bribes" in various public institutions, including hospitals. Despite such efforts, awareness among institutions about the strategy and their role in its implementation is low.[36]

Implementation and oversight of the anticorruption strategy has been weakened by operational delays regarding the Agency for the Prevention and Coordination of the Fight Against Corruption. The agency was established in 2009, but the BiH Parliamentary Assembly did not appoint a director and other personnel by the June 2010 deadline. In 2011, Transparency International BiH appealed on the Assembly to appoint a director and two deputies, which it did in August. Two unsuccessful candidates for the directorship subsequently disputed the appointments, arguing that others had finished higher on a public exam for the position.[37] Their complaint was still pending at year's end.

Despite the appointments, the agency remained defunct in 2011 because the government had not allocated the necessary office space or staff.[38] Deadlines for meeting the 2009-14 anticorruption strategy and action plan, an integral part of the EU's decision to grant BiH visa liberalization in 2010, were missed as a result.

The Public Administration Reform Coordinator's Office has the personnel and financing to implement the Public Administration Reform Strategy and Action Plan, but it lacks critical political support.[39] The civil service remains politicized, and the bloated bureaucracy in BiH enables corruption to thrive at all levels of government.

Implementation of the Freedom of Access to Information Act remained uneven in 2011. Ten years after the law was passed, only around 50 percent of responses to requests for information are granted within the deadline by public institutions subject to the law, and the information provided is often incomplete, according to Transparency International.[40]

Media coverage of corruption issues remained superficial. In August, Transparency International BiH monitored reporting on graft and misconduct in 11 newspapers, three television stations, and seven Web sites. Most of the 135 relevant reports from that period were based on one or no source. Transparency also noticed political bias. The monitored RS media, for instance, only reported on corruption cases in the FBiH or at the state level. This indicates the weak state of professional investigative reporting in BiH.[41]

Author:

Jasna Jelisić

Jasna Jelisić (City University of New York and University of Oxford, PhD candidate at the University of Sarajevo) has worked in the Western Balkans since 1997 as a journalist, political advisor, and analyst.

Notes:

[1] The responsibility for oversight of the implementation of the DPA is with the Peace Implementation Council (PIC). For details related to the composition of the PIC and its Steering Board, see Office of the High Representative (OHR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, The Peace Implementation Council and its Steering Board, http://www.ohr.int/pic/default.asp?content_id=38563. Also see Annex 10 of the DPA, which defines the OHR mandate: Office of the High Representative (OHR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, The Mandate of the OHR, http://www.ohr.int/ohr-info/gen-info/default.asp?content_id=38612.

[2] Assessing the potential for renewed ethnic violence in BiH, the Atlantic Initiative and Democratization Policy Council published A Security Risk Analysis in October that questioned the capacity of law enforcement to successfully combat serious problems such as organized crime and corruption, particularly in cases where members of the political elite and representatives of state institutions might be involved. The authors claim that under circumstances of significant political pressure, BiH police forces would split along ethnic lines and defend their ethnic group instead of keeping public order in the event of a renewed violent conflict. See Vlado Azinovic, Kurt Bassuener, and Bodo Weber, A security risk analysis: Assessing the potential for renewed ethnic violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Sarajevo: Atlantic Initiative and Democratization Policy Council, October 2011), http://www.atlanticinitiative.org/images/stories/ai/pdf/ai-dpc%20bih%20security%20study%20final%2010-9-11.pdf.

[3] Ibid., 7.

[4] In practice, the responsibility for oversight of the DPA implementation is with the Peace Implementation Council (PIC). For details related to the composition of the PIC and its Steering Board, see http://www.ohr.int/pic/default.asp?content_id=38563 . Also see Annex 10 of the DPA, which defines the OHR mandate: http://www.ohr.int/ohr-info/gen-info/default.asp?content_id=38612. The international presence transitioned into a reinforced EU mission in September 2011.

[5] The 8.2 million EUR was allocated as follows: 2 million EUR for a mine clearance project, 1.2 million EUR to technical development of projects, and 5 million EUR to the process of refugee and displaced persons return.

[6] Valerie Hopkins, "EU Confirms €96 million Aid for Bosnia, Balkan Insight, 4 October 2011, http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/eu-confirms-e96-million-aid-for-bosnia.

[7] SRNA, 27 September 2011.

[8] The High Representative, 39th Report of the High Representative for Implementation of the Peace Agreement on Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Secretary-General of the United Nations (Sarajevo: Office of the High Representative, 6 May 2011), http://www.ohr.int/other-doc/hr-reports/default.asp?content_id=46009.

[9] Toby Vogel, "Ashton agrees to negotiations with Dodik," European Voice, 13 May 2011, http://www.europeanvoice.com/article/2011/may/ashton-holds-crisis-talks-in-bosnia/71076.aspx.%C2%A0.

[10] The HR also emphasized that the RS authorities have pursued a "policy of obstructing, undermining and questioning the authority of other key state-level institutions, such as the Indirect Taxation Authority, the Electricity Transmission Company and the Institute for Missing Persons". The HR added "The same authorities have also taken unilateral action on state property, which is one of the objectives for closing the Office of the High Representative and they have continued to deny that genocide took place in Srebrenica in 1995, notwithstanding the confirmation of this fact by two international tribunals in numerous rulings." The High Representative, 39th Report of the High Representative for Implementation of the Peace Agreement on Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Secretary-General of the United Nations (Sarajevo: Office of the High Representative, 6 May 2011), http://www.ohr.int/other-doc/hr-reports/default.asp?content_id=46009.

[11] As reported by RTRS, BHT1, and Pink TV on 21 September 2011.

[12] In September the RSNA issued 120 million euros in bonds at a 8 percent interest to finance the budget deficit. It also accepted nearly 100 million euros in international loans for a public works project.

[13] Sanja Bjelica-Sagovnović, "Republika Srpska will face the Greek scenario," Interview with Mladen Ivanić, Dnevni list, 8 September 2011. The economists also predicted that BiH will enjoy no big foreign investments in the next year because of the political instability.

[14] Pulspolitical magazine, BNTV, 22 September 2011.

[15] For example, a football match in September was interrupted after a large group of fans of the Banja Luka club 'Borac' breached security and raided the pitch. They attacked fans of the Sarajevo club 'Zeljeznicar' and threw rocks at them. Violence continued on the streets of Banja Luka. Banja Luka Public Security Center spokesperson Gospa Arsenijevic said a group of 'Borac' fans injured four police officers, damaged two official police vehicles and one private vehicle. On Hayat TV, on 25 September, sports psychologist Jasna Bajraktarevic said politicians "unfortunately reached their goal as the hatred has been refreshed." Another football match was interrupted in less than a week by confrontations between Bosniak and Croats. A match between two clubs from Mostar, the Croat-dominated 'Zrinjski' and the Bosnian-dominated 'Velez,' was interrupted when 'Zrinjski' supporters broke into the pitch after 'Velez' scored a goal. As reported by numerous media on 28 September 2011.

[16] See the EU Council reaffirmation of its "unequivocal commitment to the territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a sovereign and united country" as expressed at the 3076th Foreign Affairs Council meeting in Brussels in March. EU Council, 3076th Foreign Affairs Council Meeting, Council conclusions on Bosnia and Herzegovina (Brussels: EU Council, 21 March 2011), http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/120066.pdf. In October the EU Council reiterated its "unequivocal commitment to Bosnia and Herzegovina's EU perspective, as agreed at the 2003 Thessaloniki European Council" and reaffirmed its "unequivocal commitment to the territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a sovereign and united country:" EU Council, 3117th Foreign Affairs Council Meeting, Council conclusions on Bosnia and Herzegovina (Luxembourg, EU Council, 10 October 2011), http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/125003.pdf.

[17] European Commission, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2010 Progress Report Accompanying the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2010-2011 (Brussels: European Commission, 9 November 2010), 5, http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/key_documents/2010/package/ba_rapport_2010_en.pdf.

[18] Transparency International BiH, "TI BiH apeluje na Parlament da ne propuste priliku za unapređenje zakona," (The TI BiH appeals to the parliament not to miss the opportunity to improve laws) (Sarajevo: Transparency International, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1 September 2011), http://ti-bih.org/4348/ti-bih-apeluje-na-parlament-da-ne-propuste-priliku-za-unapredenje-zakona.

[19] In the FBiH the Center for Interdisciplinary Post-Graduate Studies and the Dosta (Enough) movement became strongly perceived as aligned with the SDP BiH. At the same time, the role of civil society in the RS was negligible, as the government dominated all major communication channels.

[20] In April, Minister Suljagić ordered all primary and secondary schools in the Sarajevo Canton to remove the marks that students receive in Religious Education from overall GPAs. When leaders of all three dominant religious communities in BiH objected, Minister Suljagić tried to defend the move by explaining that students who choose to attend religious education classes end up with inflated GPAs Religious Education classes are optional, and students who opt-in usually receive high marks, improving their GPA and, thus, their university prospects.

[21] Eldin Hadžović, "Bosnian Muslim Leader Criticized Over Call for Protests," Balkan Insight, 17 May 2011, http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/the-head-of-bosnia-s-islamic-community-accused-of-hate-speech.

[22] "Promoviran Izvještaj o islamofobiji," Islamska Zajednica U Bosni i Hercegovini, 18 August 2011, http://www.rijaset.ba/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=11618&Itemid=184.

[23] Tarik Jusić, "Media landscape: Bosnia and Herzegovina," European Journalism Center, 5 November 2010, http://www.ejc.net/media_landscape/article/bosnia_and_herzegovina/.

[24] Maureen Taylor and Philip M. Napoli, "Media Development in Bosnia: A Longitudinal Analysis of Citizen Perceptions of News Media Realism, Importance and Credibility," The International Journal for Communication Studies, 2003, 473-492.

[25] Marius Dragomir, "No News is Bad News: One of Bosnia's public TV stations doesn't seem to care if anyone watches its news programs," Transitions Online, 7 February 2011.

[26] Alenko Zornia, "Postignut dogovor 15 mjeseci nakon izbora: Hrvat premijer, Srbima novac, Bošnjacima vanjski poslovi i sigurnost" [The agreement reached 15 months after the elections: Croat as a Prime Minister, money goes to the Serbs, foreign afairs and security to the Bosniaks], Vjesnik, 31 December 2011, http://www.vjesnik.hr/Article.aspx?ID=E063C5DE-6CE5-4CC3-A803-C9951DC14C94.

[27] Communications Regulatory Agency (CRA), "Godišnja anketa korisnika RAK dozvola za pružanje internet usluga u BiH za 2011" [Annual survey of users of the CRA permits for providing Internet services in BiH in 2011], http://www.rak.ba/bih/.

[28] Internet World Statistics, Europe, Bosnia and Herzegovina http://www.internetworldstats.com/europa2.htm.

[29] "Potpisan sporazum o saradnji Vlade FBiH i Saveza općina i gradova" [The Agreement on cooperation between the Government of FBiH and the Union of municipalities and cities signed], Moje vijesti, 6 October 2011, http://www.mojevijesti.ba/novost/99476/potpisan-sporazum-o-saradnji-vlade-fbih-i-saveza-opcina-i-gradova.

[30] "Public Access to Local Budgets: Making Local Government Budget Documents Easily Available to Citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina," Public policy document within the research project "Assessment of Local Fiscal Transparency in BiH", Center for Social Research 'Analitika', 13 May 2011, http://analitika.ba/files/access%20to%20local%20budgets%20PB%20april11.pdf.

[31] European Commission, Commission Staff Working paper: Bosnia and Herzegovina 2011 Progress report, Accompanying the document: Communication from the Commission to the European parliament and the Council, Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2011-2012 (Brussels: European Commission, 12 October 2011), 12, http://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/1788_1318854424_ba-rapport-2011-en.pdf.

[32] Faruk Vele, "Interview with the President of the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council Milorad Novakovic: 'MPs will not elect judges and prosecutors,'" Dnevni avaz, 16 September 2011.

[33] European Commission, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2011 Progress Report, 13.

[34] Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2011 (Berlin: Transparency International, October 2011), http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2011//cpi/2010/results.

[35] "BiH trese korpucija u zdravstvu: CCI, stanje se mora sistematski rjesavati [BiH is shaken by the corruption in the health sector: CCU- need to solve the issue in a systematic way], boboska.com, 31 July 2011, http://www.boboska.com/drustvo/2163-bih-trese-korupcija-u-zdravstvu-cci-stanje-se-mora-sistematski-rjeavati.

[36] European Commission, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2011 Progress Report, 14.

[37] Ramiz Huremagic and Blanka Benkovic said the BiH parliament broke the principles of quality, legality transparency and accountability of public service under law because the appointed director and two deputies placed third, sixth and the last in the exam.

[38] European Commission, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2011 Progress, 14.

[39] Ibid., 11.

[40] As presented by TI BiH Executive Director Srdjan Blagovcanin. "Građani moraju čekati više od mjesec dana na odgovor javnih institucija" [Citizens have to wait for the answer from public institutions for more than a month], Transparency International, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 28 October 2011.

[41] "Mediji u BiH o korupciji izvještavaju površno i senzacionalistički" [Media reporting on corruption is superficial and sensationalistic], Analysis of media reporting on corruption, Transparency International, Bosnia and Herzegovina in cooperation with Prime Communications, 20 September 2011, http://ti-bih.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Analiysis-of-the-media-reporting-Corruption-in-BH-15-28.-August-2011.pdf.