World Refugee Survey 2008 - Egypt

| Publisher | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants |

| Publication Date | 19 June 2008 |

| Cite as | United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, World Refugee Survey 2008 - Egypt, 19 June 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/485f50d06c.html [accessed 5 November 2019] |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

Introduction

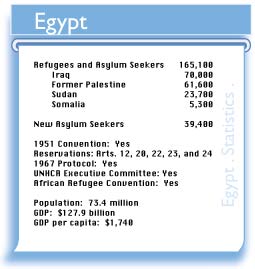

Egypt hosted some 165,100 refugees and asylum seekers, among them about 70,000 Iraqis and 61,600 Palestinians. About 23,700 Sudanese, 10,000 Iraqi, and 5,300 Somali refugees and asylum seekers registered with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). After Hamas won the Gaza elections in June, some 400 Palestinians entered. That same month, Israel stranded about 5,000 Palestinians in Al Areesh and Al Rafah in northern Sinai by sealing the border but most returned when Israel lifted the restrictions in July. There was also an increase in the number of Eritrean refugees entering the country, some seeking to continue on to Israel.

Refoulement/Physical Protection

In August, after denying them a hearing and access to UNHCR, Egypt reportedly returned – or, in the words of its foreign ministry, "asked to leave" – to Sudan at least 20 out of 48 refugees Israel had deported although Egyptian President Mubarak had reportedly promised Israeli President Olmert that he would not do so. Sudan banned travel to Israel and reportedly punished citizens guilty of it with torture, life imprisonment, or death. The Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) denied the refoulement. Egypt also reportedly deported back to Jordan and Syria Iraqis arriving by air from those countries. Jordan, in turn, forced deportees from Egypt back to Iraq.

Egypt was party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Convention), its 1967 Protocol, and the 1969 Convention governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa but with reservations on the 1951 Convention's rights to personal status, rationing, public relief and education, labor legislation, and social security. The 1971 Constitution guaranteed the right of asylum "for every foreigner persecuted for defending the people's interests, human rights, peace, or justice" but the President exercised this right only in rare, high-profile cases and Egypt had no national asylum system or procedure. A 1984 presidential decree called for the creation of a permanent refugee affairs committee within the MFA to adjudicate applications for asylum under the 1951 Convention, but under a 1954 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), the Government generally delegated the responsibility to UNHCR.

UNHCR did not give applicants copies of their interview transcripts or external reports upon which it relied. In 2006, the agency began providing rejection letters with 10 general categories of reasons that officers checked off but they did not give written explanations as to why particular categories applied to individual applicants. UNHCR did, however, give more individualized explanations orally and allowed legal advocates to hear them as well. It gave no reasons for rejecting appeals. UNHCR suspended status determinations for Sudanese in 2004, granting applicants temporary protection and planned in 2008 to continue "to proactively pursue support" for voluntary repatriation of those from the south of Sudan.

In July, Egyptian forces reportedly shot two Sudanese refugees attempting to cross over into Israel, wounding one and detaining the other. Also in July, Egyptian border guards reportedly shot and critically wounded a Sudanese refugee who was part of a group of 29 refugees entering Israel. In another incident, Egyptian security officials acknowledged killing a pregnant refugee, Hajja Abbas Haroun, and wounding four others, including a young girl, as 22 Sudanese refugees attempted to cross into Israel later that month. In August, Egyptian border guards shot and killed two Sudanese and dragged two others away and beat them to death with rocks. A week later, the body of another Sudanese man, beaten and tied, turned up near the border. Egyptian officials suggested that his Bedouin guides probably killed him in a dispute over money but an Israeli surveillance video reportedly showed that Egyptian forces shot him. In October, Egyptians shot a Sudanese refugee in the head as he and six others crossed into Israel. He later died. In two separate incidents in October, police shot and wounded two Turkish teenagers and a Turkish man trying to enter Israel along with his family. In November, border officials shot and killed an Eritrean woman who tried to enter Israel.

In January, Egypt began requiring Iraqis seeking visas to report to Egyptian consulates for interviews. As there were no consulates in Iraq and getting to Jordan and Syria became more difficult, the number of Iraqis entering fell and some families had to separate. A number of Iraqis repatriated, often more because of financial pressure than improved security in their homeland.

Detention/Access to Courts

According to the National Council for Human Rights (NCHR), Egyptian authorities detained 124 refugees and asylum seekers. These included 53 for illegal entry to a third country (50 Sudanese, 2 Somalis, and 1 Ethiopian), 27 for illegal entry (26 Eritreans and 1 Congolese), and 13 Sudanese for lack of residence permits and released them all upon UNHCR's intervention. Although the NCHR reported 15 arrests of Sudanese in June for illegal entry to a third country, Reuters put at 106 the number caught trying to go to Israel that month. The Associated Press reported separate October incidents in which authorities arrested eight Eritreans and two Darfur Sudanese trying to enter Israel and the Jerusalem Post reported five arrests of Darfur Sudanese in December for trying to enter Israel that the NCHR data did not cover. Also, UNHCR reported carrying out 122 status determinations for Eritreans in detention determining most of them to be of concern, upon which the Government released them.

In April, police arrested nine Sudanese refugees who were pressing for a meeting at the UN's offices, including women and children, on charges of riotous assembly and disturbing the peace. Police denied them access to a lawyer and detained them for four days. Later that month, a court cleared them of all charges and authorities released seven but continued to hold two in Al Qanater prison. The two had also helped organize protests against UNHCR in 2005. Police reportedly beat and deprived one of sleep and food. In August, Egyptian authorities held incommunicado 48 mostly Sudanese persons Israel had deported, 23 of whom had filed asylum claims with UNHCR, and refused to allow UNHCR access to them or to inform the agency of their whereabouts.

Egypt reportedly tried about 50 of those it arrested on the border in military courts and sentenced some to as much as a year in prison and fines up to £E1,000 (about $182). Egypt gave UNHCR access to detained refugees when authorities chose to inform the agency, but they also detained refugees without UNHCR's knowledge and refugees sometimes had to use unofficial means to inform UNHCR of their arrests.

UNHCR registered asylum seekers and renewed documentation, but refugees were also required to have residence permits and stamps on their cards for their presence to be legal. The 1954 MOU provided that the Government would issue residence permits to refugees, but refugees had to go to a number of different offices at inconvenient times and follow confusing and cumbersome procedures to obtain them. For those without formal refugee status, including Palestinians, residence permits depended on other criteria such as education, licensed work, marriage to an Egyptian, business partnership with an Egyptian, or a deposit of £E20,000 (about $3,650) to the Government. Generally, police respected UNHCR documents but schools, traffic authorities, and notaries regularly requested additional letters from UNHCR attesting to the person's status.

The 1971 Constitution reserved to citizens its principles of equality before the law, preservation of dignity and protection of detainees from harm, and restriction of detention to places the law defined. It extended its protection of individual freedom, prohibition of arbitrary arrest and detention, and exclusion of coerced confessions, however, to all persons. Refugees and asylum seekers with residence permits had the right to appear before a court when charged with a crime and, under law, the right to a translator, but this was rarely, if ever, provided. There was no record of refugees or asylum seekers using the courts to vindicate their rights under international law.

Freedom of Movement and Residence

Egypt had no refugee camps but there were reports of harassment and arbitrary identity checks by civilians and police.

The Government issued travel documents to Palestinians but did not grant them the right to reenter Egypt without a visa, which Egyptian consulates abroad summarily denied. Travelers on such documents, including refugees born in Egypt, had to return every six months or one year (with proof of education or work abroad) or the Government would deny reentry. Of the 5,000 Palestinians affected by the Gaza border closures, Egypt prevented some 1,000 from traveling abroad, where many of them had worked and studied.

The 1971 Constitution extended its protection of free movement to all persons. The 1965 Casablanca Protocol granted Palestinian refugees the right to obtain and use travel documents. The 1954 MOU with UNHCR also provided that the Government issue refugees international travel documents with visas for return but in 2006 only one non-Palestinian applied for and received one and no other had done so since 2000. The process was lengthy and restrictive and required UNHCR to liaise with the MFA and the Ministry of the Interior.

Right to Earn a Livelihood

Legal work for asylum seekers was impossible, and for officially recognized refugees nearly so, relegating both groups to the low-wage informal sector. The 2003 Labor Law required all foreigners to have a permit in order to work. The criteria included legal status, employer sponsorship, non-competition with nationals, "the country's economic need," and the hiring and training of Egyptian assistants to any foreign experts or technicians. In 2006, the Ministry of Manpower and Immigration issued a decree requiring employers to certify that applicants were not carrying the AIDS virus. Employers had to pay £E 1,000 (about $82) per year although the 2003 decree exempted those employing Palestinians with travel documents and Sudanese in the private sector. A 2005 decree extended the exemption to Sudanese in the public sector as well. The 2003 decree also capped at ten percent the number of foreigners who could work in any establishment. The 2003 Labor Law required reciprocity by a foreigner's state toward Egyptians, effectively excluding Palestinian refugees from practicing professions. Finally, the 2003 decree prohibited foreigners from working as tourist guides and, except Palestinians, in export industries.

A 2004 decree on the issuance of work permits exempted "political refugees" (in the narrow sense of the Constitution), those born in the country, Palestinians, and others from the non-competition restriction. The 2004 decree, however, also restricted professions to Egyptians unless the regulations of a profession allowed exceptions, and excluded foreigners from work in the export and import sectors, customs clearance, and tourism. Egypt did not allow reciprocal licensing of Iraqi doctors as it did Jordanians. Instead, they had to complete in-hospital training and licensing examinations and often had to work at less-qualified positions. The 2006 decree restricted earlier liberalization of work permits for domestic workers, requiring the personal approval of the Minister and limiting them to "cases necessitated by humanitarian, social or practical circumstances." The 2003 Labor Law also excluded domestic workers from its protections. Egypt maintained a reservation on the 1951 Convention's guarantee of equal protection of labor laws.

Egyptian law made no exceptions for refugees engaging in business. Under the 1997 Investment Law, foreigners could own businesses in 16 specified fields and manage corporations. The 1971 Companies Law (amended 1998) covered other areas of business and prohibited foreigners from holding majority ownership of partnerships, required the majority of board members of joint stock companies to be Egyptians, and required the employment of certain percentages of Egyptians. The 1982 Commercial Agency Law required foreigners to employ registered Egyptian commercial agents to import goods, engage in consulting, technical, or scientific services or trade representation, and to compete for government contracts. Under the 1983 Tenders Law, government contract bids by foreigners had to be 15 percent lower than those by Egyptians, to be competitive.

Under Law 56 of 1988, foreigners, including refugees, required the Prime Minister's permission to own residential property limited to 3,000 square meters, which they had to purchase with convertible currency and could not sell for five years. Law 143 of 1981 prohibited foreign ownership of agricultural or rural land. Law 230 of 1996 allowed foreigners to apply for permits to own up to two buildings of less than 4,000 square meters. Foreigners opening bank accounts required documentation from their countries of origin, which refugees and asylum seekers frequently did not have.

In 2004, Egypt ratified but did not fully implement the Four Freedoms treaty with Sudan to provide reciprocal rights for each other's nationals to freedom of movement, residence, work, and property for Sudanese, but this did not obviate the need for work permits. Egypt was also party to, but had not implemented, the 1965 Casablanca Protocol, which provided that Palestinian refugees should enjoy the right to work on par with nationals.

Public Relief and Education

The Government did not help pay for refugee aid programs and international agencies were unsuccessful in getting even registered refugees and asylum seekers public education and health services. Of the registered refugees, UNHCR was able to subsidize about 30 percent of basic needs of the neediest fifth of its caseload. Church groups also helped but were unable to fill the gap.

All Saints' Cathedral provided asylum seekers with medical services for their first two years in Egypt. Caritas, a UNHCR implementing partner, provided primary and emergency services and referrals for specialized treatment. Refuge Egypt offered HIV/AIDS testing and counseling. According to a 2005 Ministry of Health decision, foreigners, including refugees, had a right to public primary health services on par with nationals, except that only indigent Egyptians were eligible for free services other than in emergencies.

UNHCR, through Catholic Relief Services, provided education grants to about 7,000 refugee children to enable them to attend school. To qualify for the grants, one had to hold either a blue UNHCR refugee card or a yellow asylum seeker card. NGOs, many church-affiliated, ran community schools that served refugees, but most did not follow the Egyptian curriculum, the Government did not recognize them, and they did not issue formal diplomas. Only 4,200 Iraqi had enrolled in Egyptian schools but some expelled them when their three-month visas expired. A group of Iraqis including former teachers sought to establish a foreign-funded school for Iraqi students, but the Government would not register it or credit studies there. Egypt allowed Palestinians to attend colleges of medicine, pharmacy, economics, political science, and journalism, but they had to pay prohibitive foreigners' fees in hard currency, which the Government doubled for advanced degrees. Law 12 of 1996 guaranteed free education for all children in state schools but foreigners still required birth certificates, letters from embassies or UNHCR, residence permits, and certificates from previous schools in the country of origin. In 2000, the Ministry of Education instructed public schools to accept refugees with UNHCR documentation and government-issued residence permits.

Through reservations to the 1951 Convention, Egypt maintained and exercised the right to discriminate against refugees in public relief, education, and rationing. When it published the Convention in the Official Gazette, an act essential to making it law, the Government merely referred to "the reservations made to the treaty" without specifying or printing them, arguably depriving them of domestic legal force.

The Government did not directly restrict humanitarian organizations aiding refugees and asylum seekers, but the Ministry of Social Affairs, through Law 84 of 2002, regulated and monitored them closely. It also made registration of international NGOs very difficult by failing to approve them or provide reasons for rejection within the allotted time and by requiring security clearances that the law did not mandate. Both past and current development strategies including the UN Development Assistance Framework 2007-2010 did not include refugees.