Chasing the education dream

Investing in secondary education helps bring refugee youths closer to their dreams of attending university

By Tina Ghelli| 15 November 2016

Tongogara refugee camp, Zimbabwe– It’s another day of sweltering heat at Tongogara Secondary School in western Zimbabwe and teachers try to keep the students focused on their studies. However, twenty one year old Sasha Celestin does not need to be reminded to concentrate. Extremely purposeful and focused, she is the Head Girl for Form 4 at Tongogara secondary school in the refugee camp in Zimbabwe. She will complete her “O” levels in just a few weeks.

Sasha grew up in Kalemie, in the Democratic Republic of Congo in a tight knit family with her aunt and uncle living just next door to her family home. The oldest of three children, she loved to read and play with her two younger brothers, until terror and tragedy struck in 2012. Sasha tries not to think about the night when her whole world turned upside down.

A rebel group known as the Mai-Mai attacked her village burning down their home, her aunt and uncle’s home and the homes of their neighbours. Sasha and her brothers, then aged 13 and 12, managed to escape. Tragically her parents perished in the fire. Crossing rivers, hiding in the bush and eventually travelling thousands of kilometres in commercial trucks she ended up in Tongogara Refugee Camp where she lives with her two brothers taken in by her aunt and uncle who also have three young children of their own.

Feeling safe at last, Sasha set her heart on going back to school but she did not know enough English.

“I felt bad, but I knew one day I would go back to school,” she says. She spent that first year in the camp doing all that she could to learn English. She used to follow around the students going to the secondary school and asked them to teach her. Practicing with anyone who would speak to her, borrowing books from other students to try to learn new words and urging them to teach her the language, she became fluent in English. She finally managed to start school in 2013 and threw herself into studying.

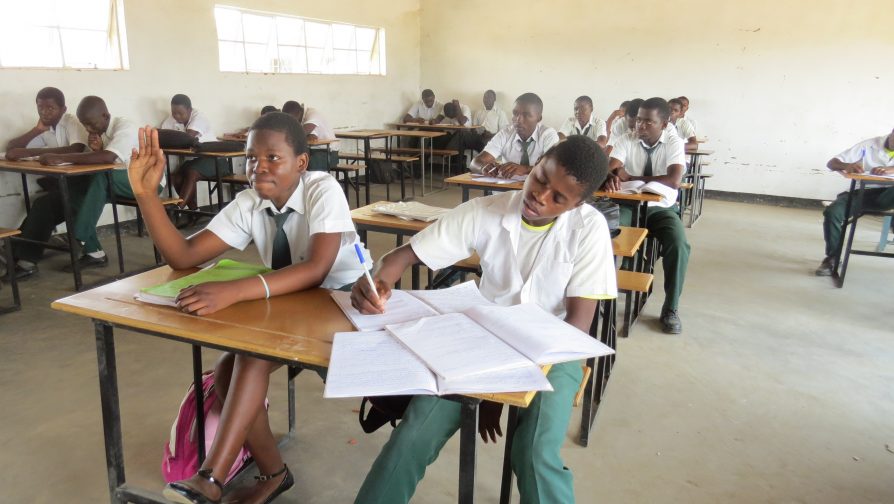

Sasha Celestin raises her hand in class at Tongogara Secondary School in Zimbabwe. Sasha hopes to one day be the first person in her family to attend university and become a lawyer. UNHCR/T. Ghelli

“The day I came to school was the happiest day of my life,” she says adding, “my favourite subjects are math, science and geography.”

Three years later, she is one of the top students in her class and obtained the position of “Head Girl.” Sasha’s goal is to attend university and study to become a lawyer so that she can defend human rights. “I can’t even tell you how badly I want to be the first person in my family to go to university,” she says.

After completing her “O” levels the next step is to go onto “A” levels. UNHCR provides funding support to some 150 refugee youth to attend an “A” level boarding school outside the camp which costs about USD 250,000 per year.

In 2015, the overall pass rate from “O” level to “A” level increased from 36 per cent to 48 per cent at Tongogara secondary school. This higher number of young people qualifying for “A” level studies, combined with an overall increase in new arrivals and budgets becoming tighter, UNHCR has been looking at other possibilities to help support young people with continuing their education.

Together with the Government, and other partners like the Jesuit Refugee Services and Terre des Hommes, UNHCR is working to upgrade Tongogara Secondary school to an “A” level school. This entails building additional classrooms and equipping them as well as increasing the number of teachers.

“We are grateful to the Government of Zimbabwe for agreeing to the upgrade of Tongogara Secondary School,” says UNHCR’s Representative to Zimbabwe, Robert Tibagwa. “If we can get the ‘A’ level courses up and running by 2018, it can be a cost effective way of ensuring that refugee children together with Zimbabweans, can complete their secondary education, but we need more support from donors to make that happen.”

According to the UNHCR report, “Missing Out: Refugee education in crisis,” released last September, 1.95 million refugee adolescents are not in secondary school. Refugees are more likely to be out of school than the global average.

The report compares UNHCR data on refugee education with UNESCO data on global school enrolment. Only 50 per cent of refugee children have access to primary education, compared with a global average of more than 90 per cent. And as these children become older, the gap becomes a chasm: only 22 per cent of refugee adolescents attend secondary school compared to a global average of 84 per cent. At the higher education level, just one per cent of refugees attend university, compared to a global average of 34 per cent.

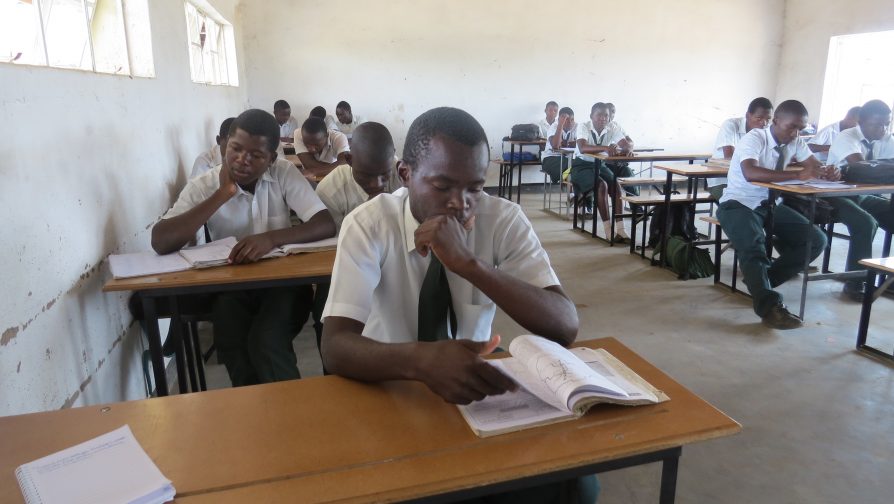

David Mulondo Gustave, aged 18, is all too aware of these odds, but he still dreams of making it to university. Taking a break from studying for his O level exams, he tells of his escape from Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo, together with his older brother in 2012. His father was a teacher and one night when they were sitting together having Sunday dinner, there was a knock on the door. One of the armed groups in the conflict shot and killed his father who was a teacher. David and his older brother ran away in one direction and his mother and then six year old brother fled in another. David still does not know if his mother and younger brother are still alive. Focusing on his dream of becoming a civil engineer helps him not to dwell on what happened in the past.

David Mulondo Gustave concentrates during class at Tongogara Secondary School in Zimbabwe. He hopes to one day attend university and become a civil engineer. UNHCR/T. Ghelli

“I like construction, buildings, bridges, they all interest me,” he says, “I want to get to university, out of the refugee camp so I can feel like a normal person. When you are in a refugee camp, you feel like you are not like the others, undermined and underprivileged. If I can go to school in a normal place I will feel normal.” He constantly thinks about his friend, Joel Tshite who won a scholarship to study in the United States. “Joel always encourages me to study hard, and I hope I too can get a scholarship too someday,” says David.

Zimbabwe currently hosts nearly 10,000 refugees mostly from the Great Lakes Region who reside in Tongogara refugee camp located about 500 kms from Harare.