Danger on the deep blue sea

As desperation mounts, more people take to the sea to find asylum or jobs. Countries should focus on saving lives, not creating deterrents.

An Italian Navy vessel prepares to assist an overcrowded boat.

© UNHCR/Alfredo D'Amato

The ocean waves crash violently against the boat, tossing it to and fro, as hundreds of men, women and children try desperately to stay on board. Behind them, they left a war zone, but none of them had been prepared for this.

They were hoping to find a better future elsewhere. Now, as the water licks their ankles and another cold night sets in, they begin to wonder if they will make it to shore at all. Surely, they think, while clutching one another, help must be on its way. But as the number of people making sea journeys in search of asylum or opportunity grows, UNHCR fears that many governments are beginning to lose focus on saving lives. For this boat, there will be no rescue tonight. Instead it capsizes off the Libyan coast, claiming over 250 lives and leaving just 19 survivors.

Like many of the 348,000 migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers across the world who have attempted a sea crossing this year, Thayer from Syria has yet to overcome the trauma of his journey. He fled the war at home with his brother and paid US$ 2,000 to board an overcrowded boat to Italy. But the vessel capsized just off the island of Lampedusa, one of two shipwrecks last October in which hundreds of people drowned.

"There was a pregnant woman with a son," Thayer recalls, his voice cracking with emotion. "They passed away. The corpse of her son was floating on the water."

Danger on the Deep Blue Sea: The number of people taking to the high seas in search of safety and opportunity has surged in 2014, often with fatal consequences.

What happened that day sparked a broad debate on asylum policy in Europe, leading Italian authorities to launch a search-and-rescue operation known as Mare Nostrum. Over the course of a year, it picked up well over 100,000 people risking their lives at sea, but has since been replaced by a new EU operation called Triton. Unlike Mare Nostrum, Triton will focus on border surveillance. It will cover a much smaller area close to the Italian coastline – and with a fraction of the budget. Now, the future of thousands fleeing war and persecution at home is at risk.

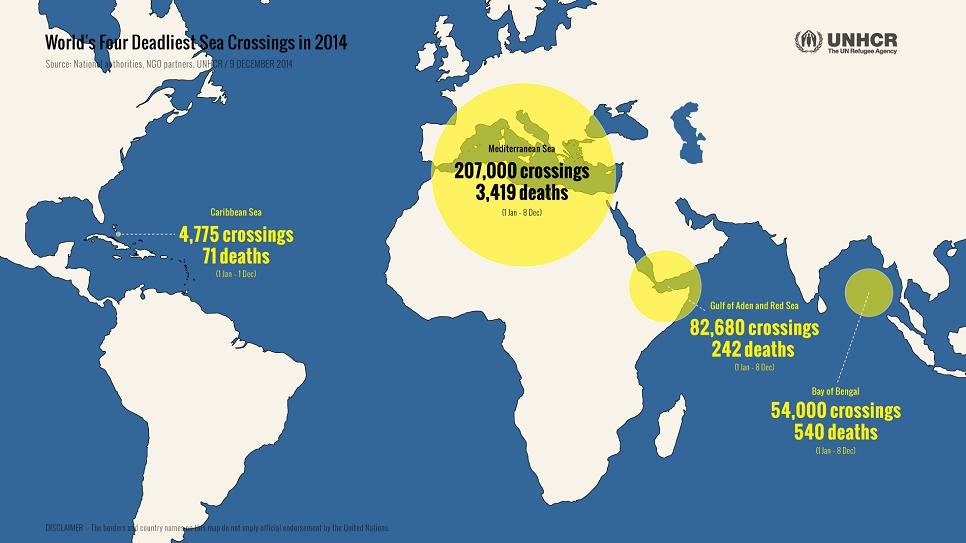

This year has seen record numbers of asylum seekers taking to the seas in search of asylum or migration – and record numbers of deaths. The flow is at its highest in southern Europe, driven partly by conflicts in Libya and Syria, with some 207,000 people known to have crossed the Mediterranean Sea since the start of January. However, there are at least three other major sea routes in use by migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers today.

In Southeast Asia, it is estimated that 54,000 people have undertaken irregular maritime journeys so far in 2014, fleeing Bangladesh or Myanmar for Thailand, Malaysia or Indonesia.

Abdullah closes his eyes as he recalls the terrifying journey he made after escaping from Rakhine State, in Myanmar. "When I saw people dying day by day, I prayed to Allah to save my life to reach Thailand safely," he murmurs. Although Abdullah survived the journey, upon arrival he was taken to a smugglers' camp, beaten and forced to work. He escaped, but still bears the scars today. "If I think of this situation, it's like I came to this place to sacrifice my life. I feel very sad."

Danger on the Deep Blue Sea: After 12 days at sea, Abdullah was taken to a camp in Thailand, where smugglers subjected him to prolonged confinement and malnutrition. Nearly paralyzed, he is learning to walk again.

Elsewhere, in the Horn of Africa region, 82,680 people crossed the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea between January and October. The Caribbean also witnessed an influx, with at least 4,775 taking the seas, hoping to escape poverty or in search of asylum.

Worldwide, UNHCR has recorded 4,272 deaths this year – over 3,400 of them on the Mediterranean alone. Among the dead were wives, husbands, brothers, sisters and children. Jihan, a blind mother of two from Syria, was among the lucky ones. "In those moments," she recalls from Greece, "I felt that I had taken my kids from one looming possibility of death to another." Mohamed, in Italy, feels equally fortunate. "My family and I, my wife and my two daughters were forced to take the boat, the boat of death. They must be called boats of death."

Meanwhile, people-smuggling networks are flourishing and exploiting those driven by desperation. Khan, from Pakistan, was forced into exile at the age of 54 after military assaults made his community unliveable. A smuggler in Lahore promised him "a better life in the West," but now, having spent his life savings, all Khan has left is hope.

Danger on the Deep Blue Sea: Saransika, a 14-year-old refugee from Sri Lanka, lost her mother and two siblings while trying to reach Australia.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres expressed concern that more and more governments see keeping foreigners out as a higher priority than saving lives and providing asylum.

"This is a mistake, and precisely the wrong reaction for an era in which record numbers of people are fleeing wars," he said. "Security and immigration management are concerns for any country, but policies must be designed in a way that human lives do not end up becoming collateral damage."

Until governments address the root causes of the problem – why people are fleeing, what prevents them from seeking asylum by safer means, and what can be done to crack down on the criminal networks who prosper from this – the dangers at sea will only continue to escalate.

Thousands have already paid with their lives. They could have been your father, your mother, your child – or even you. We must not turn our backs on more.