Yahya Hassune, doesn’t take no for an answer, quite fortunately for UNHCR.

About two years ago, Hassune was working on his first day as Associate Field Officer in Azraq, a new camp located in central-eastern Jordan that currently hosts about 26,000 Syrian refugees living in 10,000 shelters. The camp hadn’t opened yet, and Hassune was in charge of getting the shelter allocation system ready for day one. Bernadette Castel, who was the camp manager at the time, asked him:

“Imagine you are the manager of a big hotel that contains 10,000 rooms. How are you going to manage them all?”

Shelter allocation was known as a critical step that could cause significant challenges due to the high number of refugees who were expected to be processed each day. Hassune was warned by his colleagues that it would inevitably become the bottleneck of the operation. How to sort and deliver 10,000 keys, for instance, would be a headache. But instead of caving into pressure, Hassune took the warning as a challenge. At the next meeting, he promised the team that shelter allocation would run smoothly. “I told them the bottleneck would perhaps happen at the next step, but not mine,” he says.

But when he sat down to look at the system he was supposed to use to assign a shelter to each family, then manage the constant flow of people who would come in and out of the camp, he realized it was deeply flawed. The system relied on a massive and complex Excel sheet that was shared between so many users that it risked being quickly compromised. He knew that just a few errors in the dataset would make the file unreliable.

Hassune had a few notions of computer programming and Geographic Information System (GIS), a system used to capture, process and displaying geographical data. He thought Azraq would be the perfect place to use GIS for shelter allocation; unlike other camps where refugees were housed in tents, Azraq was given sturdier transitional shelters made of zinc and steel to resist harsh weather conditions. Because the t-shelters weren’t mobile, they were given a physical address, which could be used in a GIS program.

He went and submitted his idea to the camp manager, who liked it, but felt she couldn’t take the risk to implement a brand new system. She reluctantly asked him to continue using the Excel sheet, out of precaution. “If I give you the Excel sheet, will you let me do what I want?” Hassune asked. She said yes.

Staff at UNHCR’s Amman office had similar reservations. Although the idea was worthwhile, they said they didn’t have the time or resources to make it happen. So Hassune enlisted the help of Shadi Mhethawi, Associate ODM Officer and Edouard Legoupil, Information Management Officer, at the Amman office who had shown enthusiasm about the project, and together they convinced their superiors to give them permission to build a program.

They spent a month working together, Hassune making regular trips to Amman so that he could vet every step. There was no room for errors, because the code couldn’t be easily changed once the system would be up and running. “There is a rule in programming, it’s ‘garbage in, garbage out’” Hassune explains. “We made sure the program was well built, and we tested it. It was perfect.”

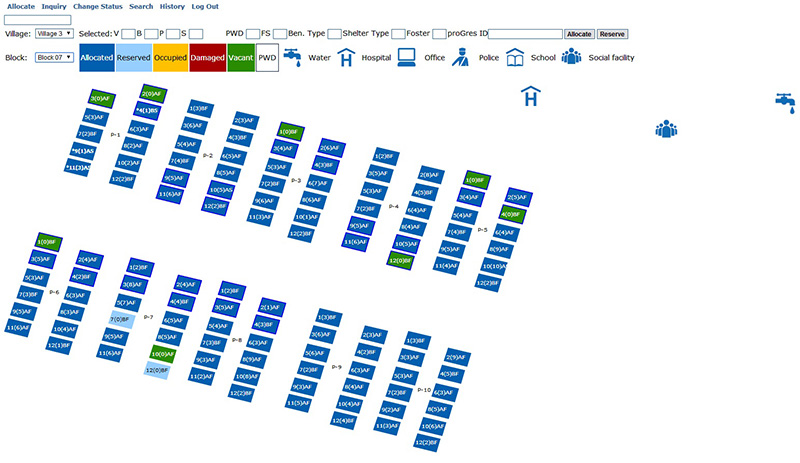

On the day Azraq opened, Field Officer Nuria Fouz paid a visit to Hassune to see how the GIS-based system was performing. What she saw astounded her; to allocate shelters, staff just had to navigate through a map of the camp to see which shelters had already been allocated, which ones were available, and how many people were living inside. Later on, the program would show additional data, such as whether the shelter had been damaged, or if it was occupied informally by another family. Staff only had to click on the desired shelter to allocate it, and the data would then feed directly into the progress file. What’s more, it only took an impressive 20 seconds to find the right key among 10,000.

A screenshot of the shelter allocation system created for Azraq refugee camp.

Nowadays, the shelter allocation team can easily process the 300 to 400 refugees who arrive at the camp each day, and Hassune says they once processed 1,600 newcomers in a single day without difficulty. “We’re not the bottleneck anymore. My colleagues at the next step have had to tell me to slow down because we were processing too fast, and they didn’t have enough space in their waiting area,” he says with a laugh. The number of staff required to work on shelter allocation has been reduced from eleven to five.

Hassune is now working on bringing minor improvements to the program, while solving the myriad other challenges that arise at the camp each day. “From the moment I wake up in the morning, I want to be at the camp,” he says.

“This is not a routine job. Each day has new adventures, and I’m always trying to identify problems and find solutions for them.”

Hassune’s spirit of facing challenges head-on was one of the reasons he was chosen as part of UNHCR’s Innovation Fellow cohort for 2016. During his Fellowship year, Hassune will define a challenge unique to his expertise, use human-centered design and prototyping principles, in addition to being connected to mentorship and funding to refine his innovative solutions.

We’re always looking for great stories, ideas, and opinions on innovations that are led by or create impact for refugees. If you have one to share with us send us an email at innovation@unhcr.org

If you’d like to repost this article on your website, please see our reposting policy.

Pingback: The human geography of displacement: mapping and profiling | cadacuanto()