Trapped Between Two Wars: Violence Against Civilians in Western Côte d'Ivoire

| Publisher | Human Rights Watch |

| Publication Date | 5 August 2003 |

| Citation / Document Symbol | A1514 |

| Cite as | Human Rights Watch, Trapped Between Two Wars: Violence Against Civilians in Western Côte d'Ivoire, 5 August 2003, A1514, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3f4f59460.html [accessed 22 May 2023] |

| Comments | This 55-page report documents widespread abuses against civilians in fighting following a September 2002 army mutiny. The abuses include summary executions, sexual violence against women and girls, and looting of civilian property by Ivorian government troops, government-supported civilian militias, and by the rebel groups. Both sides have recruited Liberian fighters, some of them from refugee camps in Côte d'Ivoire. Côte d'Ivoire's eight-month conflict was characterized by limited direct fighting between the nominal warring parties, but serious and sometimes systematic abuses against civilians. The new report documents these abuses in the west of the country, where tensions over land and proximity to Liberia exacerbated the conflict. The report calls for an international commission of inquiry to investigate abuses and recommend measures to bring perpetrators to justice, and for an extensive field-based human rights monitoring presence. It also calls on the Ivorian government to immediately stop backing the militias. |

| Disclaimer | This is not a UNHCR publication. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR, the United Nations or its Member States. |

ACRONYMS

BAE – Anti-riot brigade

BBC – British Broadcasting Corporation

ECOWAS – Economic Community of West African States

FANCI – National Armed Forces of Côte d'Ivoire

FESCI – Federation of students and schools in Côte d'Ivoire

FLGO – Great West Liberation Front

FPI – Popular Ivorian Front

ICRC – International Committee of the Red Cross

LURD – Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy

MINUCI – United Nations Mission in Côte d'Ivoire –

MJP – Movement for Justice and Peace

MODEL – Movement for Democracy in Liberia

MPIGO – Ivorian Popular Movement for the Great West

MPCI – Patriotic Movement of Côte d'Ivoire

MSF – Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders)

NGO – Non-Governmental Organization

OHCHR – Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

NPFL – National Patriotic Front of Liberia

PDCI – Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire

RDR – Rally of Republicans

RTI – Ivorian Radio-Television

UDPCI – Union for Democracy and Peace in Côte d'Ivoire

UNHCR – United NationsHigh Commissioner for Refugees

UNICEF – United Nations Children's Fund

ZAR – Refugee Assistance Zone

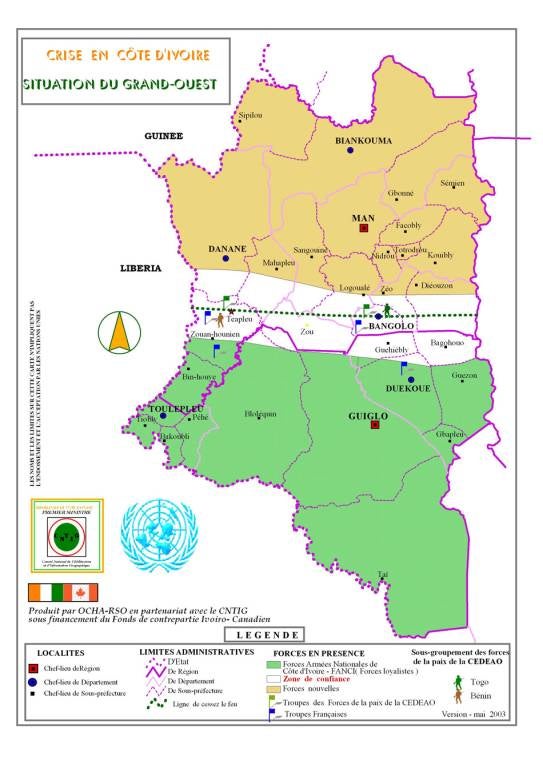

MAP OF CÔTE D'IVOIRE

MAP OF WESTERN CÔTE D'IVOIRE

I. SUMMARY

Since September 19, 2002, Côte d'Ivoire has been gripped by an internal conflict that has paralyzed the economy, split the political leadership, and illuminated the stark polarization of Ivorian society along ethnic, political and religious lines. It is a conflict that has been characterized by relatively little in the way of active hostilities between combatants, but by widespread and egregious abuses against civilians. It is a conflict that while primarily internal, developed international dimensions with the involvement of Liberian forces in the west of the country by both the Ivorian rebel groups and the government of Côte d'Ivoire.

Few of the issues at the heart of the Ivorian war – anti-immigrant feeling in the face of an economic recession, competition for resources, and the manipulation of ethnic loyalties for political gain – are unique to Côte d'Ivoire. However, the manner in which successive ruling Ivorian politicians have addressed these issues has been at best, shortsighted, and at worst, has led to serious and sometimes systematic abuses against civilians. While civilians throughout the country – and the region – have suffered directly and indirectly from the eight-month-old civil war, residents of western Côte d'Ivoire have been the main targets of killings, rape and other acts of violence committed by a variety of perpetrators. These include several massacres by both the government and rebel forces.Liberian style abuses, including looting of civilian property, sexual violence against girls and women, and recruitment of children, have also been frequent, with Liberian recruits from both sides responsible for the abuses.

Government forces and government-recruited Liberian mercenaries have frequently and sometimes systematically executed, detained, and attacked perceived supporters of the rebel forces based on ethnic, national, religious and political affiliation. Civilian militias, tolerated if not encouraged by state security forces, have engaged in widespread targeting of the immigrant community, particularly village-based Burkinabé agricultural workers in the west. Government armed forces and their allies have summarily executed, arbitrarily arrested and detained, and "disappeared" hundreds of civilians in western Côte d'Ivoire, including but not limited to the following incidents and patterns of abuses:

In a cleaning operation conducted by the government's anti-riot squad (Brigade Anti-Emeute, BAE) in Daloa in October 2002, over fifty northern and immigrant civilians were executed by members of the BAE and members of other state security forces.

- In an attack on Monoko Zohi in November 2002 by the government armed forces, at least one hundred civilians, mainly West African immigrants, were killed and buried in mass graves.

- During the government occupation of Man in December 2002, dozens of opposition and suspected rebel supporters were executed in reprisal killings.

- Government forces carried out indiscriminate and targeted attacks on civilians, killing at least fifty civilians in the west through their use of helicopter gunships.

- Liberians from the Ivorian refugee camps and from the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL) rebel faction have participated in dozens of killings, rapes, and other acts of violence against civilians in and around Toulepleu, Bangolo and Blolékin. At least sixty civilians were killed in the worst single incident documented in Bangolo in March 2003.

- Civilian militias encouraged by and sometimes working in complicity with government forces have attacked immigrant villages and harassed, assaulted and killed immigrant civilians in and around Duékoué, Daloa and Toulepleu.

For their part, rebel forces from the Patriotic Movement of Côte d'Ivoire (MPCI), the Movement for Justice and Peace (MJP) and the Liberian-dominated Ivorian Popular Movement for the Great West (MPIGO) have also attacked and killed civilians and other non-combatants suspected of supporting the government or ruling political party. Liberian and Sierra Leonean fighters allied to the MPIGO have also committed numerous abuses against civilians in the west, including killings, rape, and systematic looting of civilian property.

- MPCI forces executed over fifty gendarmes and members of their families in Bouaké in October 2002, and executed dozens of other government officials, government supporters, and members of civilian self-defense committees in other locations in the north and west.

- Members of the Ivorian rebel groups and Liberian recruits allied to the MPIGO group were responsible for the executions of dozens of Ivorian civilians in the west, including at least forty civilians killed in Dah village in March 2003.

- Liberian fighters linked to the government of Liberia and allied to the MPIGO rebel groups systematically looted the property of civilians around Danané, Zouan-Hounien and Toulepleu and committed numerous executions and other serious acts of violence against civilians while carrying out the looting.

Both government and rebel forces in the internal conflict in Côte d'Ivoire have actively engaged in the recruitment and use of child soldiers and frequently violated the rights of refugees and displaced attempting to flee areas of insecurity.

Although serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law have taken place in Abidjan and other areas of the country, this report focuses on the patterns of abuses against civilians by the main actors in the western region: the Ivorian government, the three rebel factions, the Liberian recruits on both sides, and the Ivorian civilian militias who have increasingly engaged in ethnically-motivated violence in support of the government. Most of the civilians in the west were forced to flee their homes and land due to the abuses perpetrated by Liberian fighters working with both the government and the rebel forces. Hundreds of civilians who remained in the region were subjected to violence and deprived of humanitarian assistance for most of the past six months. Once one of the most fertile areas in the country, the western region is now devastated, with serious malnutrition among its children, and the population will require sustained humanitarian and development assistance in order to restore it to its pre-war state.

Since the death of President Felix Houphouët-Boigny in 1993, successive presidents of Côte d'Ivoirehave exploited ethnic divisions to oust rivals, used the state apparatus to repress opponents, and incited hatred and fear among populations who had lived in relative peace for years. This has been compounded by a climate of impunity for state security forces and state supported civilian militias. Over the past few years, but particularly over the past eight months, opposition leaders have been targeted, civil society groups have been attacked, and press freedom has been seriously jeopardized. It is crucial that the cycle of impunity in Côte d'Ivoire, which is one of the main causes of the recent conflict, is adequately confronted by both the Ivorian authorities and the international community. It is also vital that the judiciary and other institutions related to the rule of law are strengthened.

There is an urgent need to ensure that abuses by all sides in the Ivorian conflict are fully investigated and that those responsible are brought to justice. There is also an urgent need for community-based reconciliation, which must be led by political leaders from the entire spectrum. In addition, outstanding issues that have contributed to the conflict, such as land disputes, tensions over nationality and inclusion within the political process, must be addressed promptly. Adequate support for peace-building programs, including the civilian component of the United Nations observer mission, MINUCI, will be required to assure a comprehensive, effective, and above all, an objective and equitable response to these complex issues. The international and donor community must be willing to use all means possible to press for accountability and respect for human rights, including the use of sanctions and the conditioning of aid based on respect for human rights.

II. RECOMMENDATIONS

To the Government of Côte d'Ivoire:

- Issue clear instructions to all soldiers and other security force members to respect international humanitarian and human rights law. Take immediate steps, including instructions to commanders and disciplinary action, to ensure that attacks by members of the security forces and civilian militias on Ivorian civilians, Burkinabé residents, and Liberian refugees are ended, particularly in and around Daloa, Duékoué, Guiglo and other towns in the west.

- Publicly acknowledge and condemn the unlawful killings and other abuses committed by state security forces both since September 2002 and before against members of the opposition, northerners, foreigners, and others distinguished by their religion or ethnicity. Request an international commission of inquiry to investigate abuses by all sides in the conflict and make recommendations to avoid a repetition of the events that led to conflict and to bring to justice those responsible. The commission of inquiry should also make recommendations for awarding compensation to those West African immigrants who have been victims of abuses and loss of assets and do not wish to return to Côte d'Ivoire. The findings and recommendations should be made public.

- Thoroughly investigate all allegations of violations of international humanitarian law committed by members of security forces and civilian militia and prosecute, in compliance with international standards of due process, all those individuals against whom there is prima facie evidence of such abuses.

- Immediately cease recruitment into irregular forces of Liberian refugees in Côte d'Ivoire.

- Take steps to end recruitment of all Liberian and Ivorian children and ensure that child soldiers recruited by the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL) in Côte d´Ivoire are promptly disarmed, demobilized and provided adequate humanitarian assistance and other forms of support for their physical and psychological rehabilitation and social reintegration.

- Desist from using and supporting the youth wing of the Popular Ivorian Front (FPI), the Student Federation of Côte d'Ivoire (FESCI), other youth associations and self-defense committees for security functions legally reserved for the police and paramilitary gendarmes, including checkpoint supervision; investigate and prosecute where appropriate members of any such group against whom there are allegations of the use of violence.

- Support, cooperate with, and create a conducive environment for the proper functioning of the human rights monitoring component of the United Nations Mission in Côte d'Ivoire (MINUCI).

- Cooperate with any future international commission of inquiry into abuses, and ensure by security and other measures that mass grave sites and other evidence are preserved for use by national or international investigation.

- Ratify the Rome statute of the International Criminal Court, the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families and other relevant international instruments.

To the "New Forces" (the MPCI, MJP and MPIGO rebel groups):

- Issue clear instructions to all combatants to respect international humanitarian law in all military operations, particularly as it relates to the protection of civilians and ensure that combatants and commanders receive training on international humanitarian law.

- Immediately refrain from committing abuses against civilians and enemy combatants and publicly acknowledge and condemn such abuses committed.

- End the recruitment of all Liberian and Ivorian children and ensure that child soldiers are promptly disarmed, demobilized and provided adequate humanitarian assistance and other forms of support for their physical and psychological rehabilitation and social reintegration.

- Support, cooperate with, and create a conducive environment for the proper functioning of the human rights monitoring component of MINUCI.

- Cooperate with any future international or national commission of inquiry into abuses, including through the preservation of mass grave sites and other evidence.

- Issue clear instructions to all combatants that they should allow the free return of all displaced people to areas in their control, in particular members of the Baoulé ethnic group who fled Bouaké and other locations in rebel-controlled territory.

To the Economic Community of West African States and the African Union:

- Request and provide funding for the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights to conduct a thorough fact-finding investigation into recent violence, ongoing human rights abuses, and the role of external actors such as Liberia, Burkina Faso and Liberian rebel groups in supporting the parties to the conflict in Côte d'Ivoire. The investigation team should cooperate with any future international commission of inquiry with regard to recommending compensation to those West African immigrants who have been victims of abuses and loss of assets and do not wish to return to Côte d'Ivoire.

- Press for mechanisms to be established to ensure an end to impunity for the human rights and humanitarian law violations that have taken place in Côte d'Ivoire since October 2000.

To the United Nations Security Council:

- Extend and broaden the mandate of the U.N. Panel of Experts on Liberia to investigate regional financing and support to abusive Liberian armed groups involved in the Côte d'Ivoire conflict, and consider extending the sanctions regime against those governments against whom there is evidence of such support.

- Condemn the practice of recruitment of refugees from camps by governments and rebel groups in the region and request UNHCR to take urgent measures to improve protection, in collaboration with other U.N. and non-governmental humanitarian agencies.

- Condemn the practice of recruitment of children, urge that all child soldiers be immediately disarmed and demobilized and request UNICEF, in collaboration with the government of Côte d´Ivoire, to ensure adequate humanitarian assistance and other forms of support for their physical and psychological rehabilitation and social reintegration.

- Mandate the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions to request permission from the government of Côte d'Ivoire to conduct a fact-finding mission into recent events.

- Ensure that the human rights unit of MINUCI is adequately funded, has an extensive field presence, and submits reports on ongoing human rights abuses in Côte d'Ivoire to the Security Council through the Office of the Resident Representative in Côte d'Ivoire, according to the terms of Security Council Resolution 1479. These reports should be made public.

To France and ECOWAS:

- Ensure that troops in Operation Unicorn and the ECOWAS force respect international humanitarian law and implement their mandate to protect civilians in a robust manner throughout their areas of deployment.

To the United States, France, the European Union and other international donors:

- Call publicly and privately on the Ivorian government to investigate and prosecute where appropriate all allegations of violations of international human rights and humanitarian law in connection with the conflict. Provide financial support for the establishment of an international commission of inquiry.

- Refuse all military or police assistance to the Ivorian government, with the exception of human rights training programs, until good faith investigations have taken place and accountability for reported abuses by the security forces has beenestablished.

- Fund humanitarian and development programs addressing the urgent humanitarian needs in western Côte d'Ivoire, including programs focusing on health, education, agricultural assistance, demobilization and reintegration, and community reconciliation.

- Ensure and prioritize programs for the strengthening of the Ivorian judiciary and other institutions essential to the rule of law.

- Support financially and through public statements local civil society organizations in their efforts to promote and protect human rights and support freedom of the press in Côte d'Ivoire.

III. BACKGROUND

Côte d'Ivoire was largely stable for thirty years following its independence from France in 1960. Under the leadership of President Felix Houphouët-Boigny, an ethnic Baoulé and Catholic, over sixty ethnic groups coexisted with over three million immigrants from the West African sub-region, if not in harmony, at least without overtly exposing the fragility of the Ivorian state. Ethnic tensions were certainly present and were occasionally violently checked during Houphouët-Boigny's rule,1 but an open-door policy on immigration helped to build a thriving agricultural economy. Côte d'Ivoire's special relationship with France, which backed Houphouët-Boigny throughout his rule and assured his regime's security, also contributed to the country's relative stability. Houphouët-Boigny's Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (Parti Démocratique de la Côte d'Ivoire, PDCI) monopolized political activity in the single-party state, but his PDCI governments nominally reflected the ethnic and religious make-up of the country. Côte d'Ivoire was the economic motor of a region that, while rich in resources, remained poor in governance and accountability.

The recent, apparently rapid unraveling of a country once known as the "Ivorian miracle" can be traced to factors stretching back several decades: political ambitions long checked under Houphouët-Boigny's autocratic single-party rule, an economic recession tied to dependence on coffee and cocoa exports, increasing competition for natural resources, an agricultural system heavily dependant on migrant labor, and weak state institutions. The conflict also has more immediate causes, specifically, a divisive political discourse based on ethnicity and the increasing impunity of state security forces in the face of clear-cut responsibility for violations of human rights. Regional factors including the proximity of the neighboring Liberian conflict, the easy circulation of arms and mercenaries, and the willingness of Burkina Faso to provide support to the nascent MPCI, have also served to draw Côte d'Ivoire into a complex regional quagmire.

Economic recession and immigration

By the 1990s, Côte d'Ivoire had become the world's leading producer of cocoa and was among the top five producers of coffee, mainly built on the large-scale immigration of agricultural workers from neighboring countries – in particular, Burkina Faso.2 These statistics masked a troubled economic picture as Côte d'Ivoire struggled to emerge from serious economic recession in the 1980s. The impact of the economic recession and structural adjustment measures imposed by international financial institutions and donors affected not only the cocoa and coffee sector, where commodity prices dropped and subsidies to farmers were cut, but also general employment opportunities. Many educated urban youth returned to the villages seeking a future, but became unemployed villagers – "chômeurs villageois" – instead.3

The economic recession coincided with increasing competition for natural resources in several areas of the country: in the west and southwest – traditionally forest land – only 17 percent of the forest remained by 2000.4 In the north, tension over land in the cotton belt had became a source of pressure, while in the west, the heart of the cocoa and coffee plantations, the collapse of agricultural commodity prices and subsidies to cocoa farmers resulted in increasing friction between the immigrant plantation workers and the Ivorian villagers who had sold or rented them land.

In the midst of the economic crisis and facing diminished popular support in the lead-up to the 1990 elections, particularly from his traditional constituency in the agricultural sector, Houphouët-Boigny's government introduced residence cards for non-nationals in 1990 in a bid to gain more state revenue and increase PDCI votes. While the measure did shore up PDCI support in the short-term, assisting Houphouët-Boigny to win the election, the perception that immigrants had been granted illegitimate status through fraud was to contribute to considerable future problems. Many northern Ivorians and Burkinabé immigrants dated the start of institutionalized harassment and extortion by state security forces to the issuance of these residence cards in 1990.5 For many northern Ivorians the card checks were particularly galling because the southerner-dominated state security forces did not distinguish between northern Ivorians and immigrant residents. In addition, many members of the security forces used the opportunity of card checks to regularly extort money from both groups.6

Ivoirité: ethnic discrimination for political gain

Ethnically, Côte d'Ivoire can be described as a crossroads, with most of the major ethnic groups migrating from neighboring countries over the centuries.7 While there has been substantial mixing of these populations geographically, particularly in Abidjan, Daloa and other urban centers, the country remains roughly divided into regional blocs. The center and east are mainly occupied by the Baoulé and Agni, both part of the Akan migration from Ghana. The north is largely home to two main ethnic groups: the Malinké and Dioula (part of the northern Mande group) who migrated from Guinea and Mali, and the Senaphou and Lobi people (part of the Gur group) who migrated from Burkina Faso and Mali. The west is populated by the southern Mande group – largely the Dan or Yacouba and Gouro ethnic groups, who migrated from southern Guinea and Sierra Leone. Finally, the southwest is home to the Krou peoples, including the Bété and Wê (a sub-group of whom are known as the Gueré) who are believed to be among the earliest migrants from the southwestern coast.

The death of Houphouët-Boigny in 1993 marked the onset of overt political tension in Côte d'Ivoire and the end of the fragile ethnic balance he had maintained.8 Candidates representing the key major ethnic groups, including Houphouët-Boigny's Baoulé successor, Henri Konan Bédié of the PDCI, Laurent Gbagbo the Bété leader of the Popular Ivorian Front (Front Populaire Ivoirien, FPI), and Alassane Dramane Ouattara of the Rally of Republicans (Rassemblement des Républicains, RDR) began vying for the presidency in the run-up to the 1995 elections. Bédié's 1995 campaign was based on an ethnic platform aimed at undermining support for Bédié's main rival: Ouattara, a former prime minister under Houphouët-Boigny and the candidate of the largest opposition party, the heavily northern-supported RDR. The RDR boycotted the election after Ouattara's candidacy was barred on the grounds that he held Burkinabé nationality and was not a native Ivorian, and Bédié won the election.9

Following Bédié's accession to the presidency, the relationship between the immigrant – mainly Burkinabé – community and the Ivorian government changed for two main reasons. First, it rapidly became clear that the new president, Henri Konan Bédié's vision of the role and position of immigrants in Côte d'Ivoire differed radically from his predecessor, who had embraced an "ethnic coalition" strategy involving the Baoulé and the northerners.10 Under Bédié, the introduction of the rural land reform law was one signal of a clear change of policy.11 A second element was the way in which Bédié reacted to the creation of the opposition party led by former Prime Minister, northerner, Muslim and presidential rival Alassane Ouattara. The ensuing debate over Ouattara's nationality and eligibility for the presidency became a symbol of the deep-seated divisions over the issue of "ivoirité," the question of Ivorian identity and the role of immigrants in Ivorian society.

During Bédié's six-year rule allegations of corruption and mismanagement multiplied, and he increasingly relied on ethnicity as a political tactic to garner support in an unfavorable economic climate.12 In 1999, Gen. Robert Guei, a Yacouba from the west and Bédié's chief of staff, took power in a coup following a mutiny by soldiers. Initially applauded by most opposition groups as a welcome change from the longstanding PDCI rule and Bédié's corrupt regime, Guei's pledges to eliminate corruption and introduce an inclusive Ivorian government were soon overshadowed by his personal political ambitions and the repressive measures he used against both real and suspected opposition.13 Throughout 2000 – another election year – Ivorian politics became increasingly divided on ethnic and religious lines. Ouattara's candidacy remained in contention, and increasing friction between Guei and the RDR led to the RDR's withdrawal from the single ministerial post it was accorded by Guei's transitional government in May 2000.14

The presidential and parliamentary elections of 2000

The cumulative political, economic, religious and ethnic tensions of the 1990s erupted into violence during the presidential elections in October 2000.15 The legitimacy of the elections was seriously compromised by the exclusion of fourteen of the nineteen presidential candidates, including Alassane Ouattara and the PDCI candidate, former president Bédié. General Guei fled the country on October 25, 2000 after massive popular protests and the loss of military support followed his attempt to entirely disregard the election results and seize power. Laurent Gbagbo was installed as president a day later, but the death toll continued to mount as RDR supporters -- calling for new elections -- clashed with FPI supporters and government security forces.

Under President Gbagbo's regime, ethnic and religious splits deepened as security forces and vigilante groups again clashed with supporters of the RDR in the lead up to the December parliamentary elections. Ouattara was again disqualified by a Supreme Court decision questioning his citizenship and the RDR subsequently boycotted the elections. A state of emergency was imposed following violent clashes in Abidjan in December 2000, but the parliamentary elections went ahead in all but twelve northern districts.

Over 200 people were killed and hundreds were wounded in the violence surrounding the October and December elections. Demonstrators were gunned down in the Abidjan streets by the state security forces; hundreds of opposition members, many of them northerners and RDR supporters targeted on the basis of ethnicity and religion, were arbitrarily arrested, detained and tortured, and state security forces committed rape and other human rights violations in complicity with FPI supporters. In the worst single incident attributed to gendarmes from the Abobo base in Abidjan, the bodies of fifty-seven young men were discovered in Youpougon, on the outskirts of Abidjan, on October 27, 2003, a massacre that became known as the Charnier de Youpougon. A United Nations inquiry into the massacre concluded that the responsibility for the massacre rested squarely with members of the gendarmerie, yet those responsible for the killings and other election-related violence have yet to be properly investigated and brought to justice. The April 2001 trial of eight paramilitary gendarmes in connection to the Youpougon massacre led to their acquittal due to "lack of evidence".16 Although the government of Côte d'Ivoire stated its intention to reopen the investigation in 2002, this initiative has been put on hold since the war began in September 2002.

In late-2001 and early-2002, President Gbagbo organized a reconciliation forum which included the representatives of all four key political parties: Gbagbo's FPI, Ouattara's RDR, Bédié of the PDCI and Guei's Union for Democracy and Peace in Côte d'Ivoire party (Union pour la Démocratie et pour la Paix en Côte d'Ivoire, UDPCI). Despite this largely symbolic gesture, political tension remained high in several parts of the country as local municipal elections approached in July 2002. In the west, where the political campaign inflamed the pre-existing tensions over land, young supporters of the FPI, PDCI and RDR clashed in Daloa in late-June 2002, resulting in at least four deaths and the burning of two mosques and a church.17 The violence also spread to villages around Daloa, where groups of young Bété, Gueré, Burkinabé and northern Ivorian villagers burned each other's villages and homes and thousands were displaced to Daloa and Duekoué.

September 2002: from army "mutiny" to civil war

In August 2002, President Gbagbo announced a government of national reconciliation, with representation of the four principal political parties in his cabinet. General Guei, however, refused to accept the cabinet post reserved for his UDPCI party. Shortly thereafter, early in the morning of September 19, 2002, heavy shooting broke out in Abidjan while simultaneous attacks took place in the northern towns of Korhogo and Bouaké.

Initial speculation on the backing for the attempted coup centered on Guei. However General Guei, his wife, and Boga Doudou, the Minister of the Interior, were all killed on September 19 in Abidjan. It soon emerged that the uprising was initiated by soldiers who had been recruited into the army by Guei and feared demobilization under President Gbagbo, and that the "mutiny" was in fact an organized rebel movement, the Patriotic Movement of Côte d'Ivoire (Mouvement Patriotique de Côte d'Ivoire, MPCI) whose origin was rather less spontaneous than it first appeared.

The attempted coup was led by a number of junior military officers who had been at the forefront of the 1999 coup, but left President Guei's regime after he became increasingly hardline. Several of the officers were detained and tortured under Guei and had fled to Burkina Faso, where they certainly received training and possibly other forms of support in the two years between their exile from Côte d'Ivoire and their return on September 19, 2002. The total number of MPCI troops in the first weeks of the mutiny is estimated to have been no more than about eight hundred and recruitment of additional forces took place, particularly in Mali and Burkina Faso. At least five hundred Maliens joined up in September 2002, lured by promises of 10,000 CFA (approximately $17) per day.18 However, many returned in early-2003 after the money supply dwindled. The MPCI also recruited hundreds of "dozos," traditional hunters with family hunting rifles who are a common sight in rural Côte d'Ivoire, Mali and southern Burkina Faso. At least some of the dozos recruited by the MPCI were Burkinabé and Malien immigrants who were long-time residents of Côte d'Ivoire.

The government's initial response to the rebellion was to launch a security operation in the economic capital, Abidjan. This consisted of hundreds of security force members descending on low-income neighborhoods – the "quartiers précaires" or shantytowns – occupied by thousands of immigrants and Ivorians. During these operations they allegedly searched for weapons and rebels, but more often would simply order all out all the residents and burn or demolish their homes. Allegedly conducted in order to secure Abidjan from suspected rebel infiltration, the raids displaced over 12,000 people – mostly foreign immigrants. They were accompanied by numerous serious human rights abuses, including arbitrary arrests and detentions, "disappearances," rape, and summary executions. In addition, extortion by the security forces was widespread and commonplace.19 Dozens of neighborhoods were affected through October 2002, when the government officially suspended the operation as a result of international protests. Unofficially however, the demolitions and abuses continued well into December 2002 and later.20

By the end of September 2002, the MPCI rebels, composed mainly of "Dioula"21 or northerners of Malinké, Senaphou and other ethnicities, some Burkinabé and Malien recruits, and the "dozos," were in control of most of northern Côte d'Ivoire (approximately 50 percent of the country), including Bouaké, Korhogo and Odienné towns. The ease with which the MPCI captured this area was largely due to the fact that they encountered minimal opposition. While many questions remain unanswered regarding the origins of the Ivorian rebel movements, the MPCI group is the most organized, disciplined and ideologically straightforward. Its main stated aims were the redress of recent military reforms, new elections and the removal of President Gbagbo, whose presidency was perceived as illegitimate given the flawed elections that took place in 2000. However, it also represented other grievances, including the widely held feeling of many northern Ivorians that they were consistently politically excluded and systematically discriminated against over the past decade.22 While the core of the MPCI was northern Ivorian – such as Senaphou and Malinké – its membership at both the troop and high political levels included most Ivorian ethnic groups, including Baoulé and Bété members.

A government offensive on Bouaké in early October saw heavy fighting in and around the city and the flight of thousands of civilians, but the MPCI retained control of the town. An MPCI advance in the west captured Vavoua on October 7, 2002, and Daloa on October 12, 2002. The MPCI advances in the north and west were accompanied by reports of summary executions of gendarmes and suspected government sympathizers. Daloa, a key town in the country's cocoa belt, and the transit point for much of the cocoa heading to the coastal port of San Pedro, was re-captured on October 14, 2002 by the government forces who then proceeded to comb the town for rebel supporters. Several days later, the government signed a cease-fire with the MPCI. French military forces already present in the country as part of a long-standing security agreement agreed to monitor the cease-fire line.

Peace negotiations took place at the end of October 2002 in Lomé, Togo. Both sides agreed to refrain from "the recruitment and use of mercenaries, enrollment of children, and violations of the accord on cessation of hostilities."23 Member states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) also pledged to deploy a peacekeeping force in Côte d'Ivoire. Despite the cease-fire, reports continued to rise of assassinations of immigrants, RDR leaders and supporters, and suspected rebel sympathizers by "death squads" composed of members of the security forces and civilian vigilante groups in Abidjan.

The war moves west: November 28, 2002

In the end of November 2002, the capture of Man and Danané and an attack on Toulepleu, all sizeable towns in the west near the Liberian border, marked the appearance of two new rebel groups and a new military front. The new groups, the Movement for Justice and Peace (Mouvement pour la justice et la paix, MJP) and the Ivorian Popular Movement for the Great West (Mouvement Populaire Ivoirien du Grand Ouest, MPIGO), claimed to be Ivorians pursuing vengeance for General Guei's death.24 However the MPIGO group was mainly composed of Liberian and Sierra Leonean fighters, including some former members of the Sierra Leonean rebel group, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) and Liberian forces linked to Liberian President Charles Taylor. While the MPCI initially denied links with the two new groups,25 there were signs that the western offensive on November 28 was coordinated among the three groups. Certainly the emergence of the two western groups and the opening of another military front came at an exceedingly opportune time for the MPCI, which had signed a cease-fire with the government and could not pursue further military gains without violating this agreement.26

The MPIGO group quickly moved south from Danané along the Liberian border, capturing Toulepleu on December 2. It then moved east towards Guiglo and captured Blolékin on December 7, 2003. Meanwhile, the government forces recaptured Man on November 30. In December 2002, both sides reinforced their troops with fresh recruits, including additional Liberians on the rebel side and a new force of Liberian troops fighting alongside the government. The French military force monitoring the initial cease-fire line, known as Operation Unicorn, also received additional troops until it numbered almost 2,500 by the end of December 2002. Fighting continued in late-December and resulted in a rebel counter-offensive re-capturing Man and Bangolo and a series of clashes between French forces and the western rebels around Duékoué as the rebels sought to push their offensive further south.

January 2003 brought further fighting and increasing reports of abuses against civilians in the west. French diplomacy produced a second cease-fire agreement between the government and western rebel groups on January 13, 2002, but peace talks convened by the French government in Linas-Marcoussis were plagued by reports of on-going fighting along the Liberian-Ivorian border.

The Paris negotiations produced the framework for a new government of reconciliation in which President Gbagbo retained the presidency while delegating most substantive powers to a new prime minister selected through consensus. In an annexe, the Linas-Marcoussis accords also tasked the new government of reconciliation with legislative reform of the laws on nationality, electoral procedure, and land inheritance. Human rights concerns featured prominently in the agreement, which required the immediate creation of a national human rights commission, the establishment of an international inquiry into grave breaches of human rights and international humanitarian law, and demanded an end to the impunity of those responsible for summary executions, in particular the death squads.

The signing of the Linas-Marcoussis peace accords by all the warring parties on January 25, 2002 was followed by four consecutive days of street demonstrations in Abidjan, mainly by the "young patriots," youth supporters of the FPI who protested the verbal allocation of two key ministries – Defense and Interior – to the rebel groups. President Gbagbo's return to Abidjan did little to subdue the protests. Instead, his public statement that the accords were "propositions" cast doubt on his commitment to the agreement. In early February the United Nations Security Council issued a statement of support for the accords and gave Chapter VII authorization to the French and West African troops to protect civilians in their zones of operation.27 Following the protests in Abidjan, an impasse ensued on the political front throughout February and most of March 2003, despite numerous efforts to further the peace process. A summit in Accra in early March resulted in the preliminary distribution of cabinet posts in the new government of reconciliation, as fighting continued in the west of the country.

As talks continued over the next steps in the peace process, reports of massacres emerged from the west, where it became increasingly clear that both the government and rebel forces were using Liberian fighters in a proxy war. Throughout March and early April, MPCI-appointed members of the government refused to take their seats in Abidjan citing security concerns. Security in the Toulepleu area declined as Liberian fighters on both sides fought each other and launched attacks into neighboring Liberia. Thousands of civilians fled the west for the increasingly uncertain refuge of Liberia and Guinea.

International and local concern over the situation in the west mounted through April, culminating in a meeting between Liberian President Charles Taylor and President Gbagbo in Togo in late-April, and an agreement to monitor the border through a quadripartite force composed of Ivorian government and rebels forces, Liberian forces and French/ECOWAS forces.28 A cease-fire was signed in early May as members of the government of reconciliation took their seats in Abidjan for the first time. A United Nations mission – MINUCI – composed of military liaison personnel and civilian human rights monitors was also approved by the United Nations Security Council in early May. By late-May, the security situation in the west was improving as many of the Liberian fighters left the area, but the humanitarian situation remained dire, with large numbers of civilians lacking access to clean water, food and health care. In early June French and ECOWAS forces moved in to secure the major towns in the west and monitor the cease-fire, and the curfew was lifted.

IV. THE "WAR IN THE MOUTH": THE ROLE OF POLITICAL RHETORIC AND THE MEDIA

"Even before the war began, there were dialogues of war' among Ivorians. There was no war on the ground, but there was war in the mouth." Ivorian refugee, Nonah refugee camp, Guinea

Throughout over ten weeks of interviews with victims and witnesses to the violence in Côte d'Ivoire, Human Rights Watch was consistently told – by Ivorians, Burkinabé, long-time observers, victims – that the Ivorian media and the political discourse of key politicians played a crucial role in inflaming tensions, inciting fear and hatred, and galvanizing conflict, not only since September 19, 2002, but long before.

The role of the Ivorian media

Côte d'Ivoire is home to a plethora of media: at least a dozen daily newspapers have wide circulation in the capital and major towns around the country. Local and international radio programs have a wide audience, and both Ivorian and international television programs are available in Abidjan and in many large and small towns. Yet the variety of media available to Ivorians, probably unmatched in any other country in the region, has not guaranteed access to objective news coverage for two main reasons.

First is the politicization of the Ivorian media, particularly the print media, which almost entirely lacks independence, given its links to the main political parties. Each major political party has a newspaper that acts as its mouthpiece, voicing its policy and propaganda. Since most of these newspapers lack objectivity, their audience receives at best partial, and at worst, false and inflammatory impressions of events. Second, while the Ivorian literacy rate is above average for the region, it remains below 50 percent,29 particularly in the rural areas, where radio remains the principal source of information.

When the "mutiny" began, the government moved quickly to ensure that Ivorians could no longer access independent media. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and Radio France Internationale (RFI) programming on FM frequencies were cut within a week of September 19, 2002, thereby eliminating access for the vast majority of rural villagers to independent radio coverage of the conflict. Television soon followed – by October 7, 2002, the French channel TV5 was taken off the air. The combined blocks on both radio and television cut access to independent media programming for the majority of the Ivorian population.

The government simultaneously began a campaign to vilify the international press and their coverage of Côte d'Ivoire, not only by cutting audience access, but in some cases through intimidation of individual journalists. Local opposition media also suffered badly, with repeated attacks on the offices and persons of particular opposition papers.

The lack of objective coverage by local media worsened with the onset of the conflict in September 2002 and the increase in "patriotic" fervor.

Political discourse: before and after September 19, 2002

The Ivorian media and the political discourse of high-level politicians inflamed popular feeling, especially among the groups of rural and urban youth, both before and after the conflict began. A witness to the rural inter-communal violence over land in 2002 told Human Rights Watch, "[e]veryday, the radio incited people to disputes."30

After September 19, the situation worsened. Ivorian "patriots" were exhorted to mobilize. In late-October, civilians were encouraged by government statements to obstruct the access routes to Abidjan and form "vigilance committees" to "neutralize any assailant who attempted activities in Abidjan."31 Television broadcasts and newspaper photographs of captured "assailants," bound, with weapons at their sides, were frequently shown. Displaying the captives, who were mainly northerners and immigrants, heightened popular feelings against these groups. Sometimes the images of immigrants were shown in conjunction with thinly veiled or outright accusations of foreign support to the rebels (generally assumed to be Burkina Faso). These statements appear to have contributed to heightened hostility and attacks on the immigrant community. A witness to the violence against the Burkinabé in villages around Duékoué said: "Television – when it says the Burkinabé are assailants' – that inflames the youths."32

Government statements were sometimes ambivalent, sometimes ominously clear. As the rebels' success grew and the weakness of the defending government forces became more apparent, the government's position hardened. As its forces lost Bouaké, Vavoua and then Daloa, public statements issued on the national television program and in the print media by members of the government sent alarming signals. Telephone hotline numbers were set up for the public to phone in their denunciations of suspected rebels and the official spokesperson for the Ivorian armed forces at that time, Lieutenant-Colonel Jules Yao Yao, stated on October 11 that "all those who assist the assailants or act alongside are considered as accomplices and will be treated pure and simply as military objectives."33 Yao Yao continued, "It is the same for all the patriots who might be tempted by reprisals. They fall beneath the force of the law." Despite this latter qualification, Human Rights Watch's research indicates that many abuses were committed by civilian "patriots" or members of self-defense committees, sometimes in collaboration with the state security forces, and these cases were neither investigated nor prosecuted (see below, chapter IX).

V. ATTACKS ON CIVILIANS AND OTHER NON-COMBATANTS BY GOVERNMENT FORCES

Since the outbreak of the conflict on September 19, 2002, civilians have been the victims of widespread and systematic violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by the Ivorian armed forces (Forces Armées Nationales de Côte d'Ivoire, FANCI), members of the state security forces such as the gendarmes and police and individuals working in collaboration with government forces.34 These violations include systematic and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, summary executions of civilians and other non-combatants, arbitrary arrests and detentions, "disappearances," torture, corporal punishment and other violent acts against civilians, rape, destruction of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, and pillage. The perpetrators of abuses include 1) the government forces; 2) mercenaries working with and recruited by the Ivorian government, including Liberian fighters from the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL) rebel group; and 3) state-supported civilian militias.

In all three patterns of abuse documented by Human Rights Watch, civilian victims were targeted based on ethnic, religious, national or suspected political affiliation. In many cases, the victims' names alone were considered grounds for arbitrary arrests, detentions, torture and executions, based on the identification of the name as a potential northerner or immigrant or political opposition member. Victims have also been targeted on the basis of religious affiliation, for instance, Muslims have often been assumed to be supporting the rebel forces, imams have been killed, and mosques have been attacked. Members of certain professions have also been victims of abuses: drivers and owners of transport businesses have been targeted by government forces, apparently due to suspicions of their involvement in transport and supply of arms and funding to the rebels. Another motive for the targeting of transporters and businesspeople may have been the dominance of "Dioula" northerners and immigrants in this field.

Some of the targeting of political opposition and suspected rebel sympathizers was done with premeditation and planning. Numerous witnesses told Human Rights Watch of the existence of lists of names that circulated among units of the government armed forces in Daloa, Guiglo, Vavoua, and other locations. In several cases, witnesses escaped after being warned of the existence of the lists by friendly government contacts. In most cases these lists appear to have been created with assistance from local villagers and townspeople sympathetic to the government. In some cases however, the names on the lists may have originated in Abidjan.

Widespread and systematic killings of civilians by the government armed forces and irregular forces affiliated to the government took place during offensives and counteroffensives on towns like Vavoua, Man and Toulepleu. They also took place during "cleaning" operations conducted by paramilitary groups such as the anti-riot squad (Brigade Anti-Emeute, BAE) in towns re-taken from the rebels, such as in Daloa in October 2002. These operations on the ground were sometimes accompanied by indiscriminate or targeted helicopter attacks in which civilians were the principal victims.

Summary executions of civilians

The attacks on civilians – particularly the killings in places like Daloa, Monoko-Zohi, and Man – appear to have been carried out with the aim of systematically eliminating all individuals suspected of supporting the rebels. The targeting of specific individuals was often undertaken with the assistance of part of the local civilian population, mostly Bété or Gueré youth groups or civilian militias. Human Rights Watch received numerous accounts describing how civilians pointed out potential supporters of the rebels to the government armed forces. Based on lists of names and on this physical identification of homes by civilians, members of the government forces would then arbitrarily arrest and execute the individuals. Human Rights Watch gathered information on over 250 cases of summary executions by the Ivorian armed forces in a variety of towns in the west and verified over forty such cases. This figure does not include the dozens of individuals who were last seen in government custody and have "disappeared" or the dozens of cases of individuals who were killed in remote settlements in rural areas, and is therefore very likely a serious underestimation of the total number of victims. It also does not include the estimated hundreds of victims of assassinations in Abidjan and other areas in the southwest.

The first such large-scale series of summary executions by government forces documented by Human Rights Watch took place in Daloa in October 2002, after the government regained control of the town.

The "cleaning" of Daloa: October 15-20, 2002

Daloa town lies in the Haut-Sassandra region, originally a largely Bété area where substantial numbers of northerners and immigrants have settled in both the town and the rural villages over the years. Ethnically, the town and region of Daloa have changed enormously in the past decades due to internal migration and immigration. While the Bété retain a substantial presence in the area and a strong affiliation for the ruling FPI party, the population of northern Ivorians and Burkinabé immigrants has grown significantly. In March 2001, the RDR won the municipal elections, giving the town its first RDR mayor and providing a serious shock to the Bété and others who supported the ruling FPI party. Daloa is among the largest towns in the country and a key transit point for crop harvests, given its location on the edge of the cocoa, coffee and cotton belts, and its road connections to San Pedro, Yamassoukrou and Abidjan.

The MPCI rebels moved south from Vavoua and arrived in Daloa on October 11. Clashes with loyalist forces took place in the Lobia II quarter for several hours on the evening of October 11, resulting in the rebels capturing Daloa on October 12 and occupying the various military camps. Loyalist reinforcements, including Angolan mercenaries, arrived in the afternoon on October 13, and fighting recommenced, continuing until dawn, when the government forces re-captured Daloa. One individual, who was involved in the collection of the corpses following the fighting noted, "we counted about sixteen bodies, of which eight were collected from the military camp after the fighting and others were found around the camps of the gendarmerie."35 These bodies were combatants from both sides.

So-called cleaning-up operations began in the town, initiated by the forces of the Brigade Anti-Emeute (BAE) – the paramilitary, anti-riot squads – who arrived in Daloa on October 14, 2002. On October 15, an article in the government newspaper Notre Voie stated that "the assailants found refuge in the quarters of the Dioula, who are favorable to them." The article continued, "certain guns abandoned by the aggressors were collected by young RDR members who, since the beginning of the Daloa attack, have done nothing but support the actions of the terrorists, applauding them in their passage through their quarters."36

Whatever the truth of the last allegation, between October 14 – 20, after the loyalists had regained control of the town, more civilians died as a result of summary executions by government forces than in any of the fighting of the preceding days. According to credible sources, the "ratissage" or combing operation of the BAE resulted in the killings of at least fifty-six people. Among these, forty-two were identified, many of them rich immigrant businessmen, RDR supporters, or known to be involved in transport.37 The consul of Mali in Daloa – Bakary Touré – was among the victims. At least ten people were arbitrarily arrested and detained by the state security forces and their whereabouts are unknown. Additional bodies of unidentified individuals were buried in mass graves in Daloa. Of the victims identified by families or local authorities, 90 percent were immigrants from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea or Ivorians of northern ethnicities.

Witnesses to the events described a similar scenario in most cases. The victims were arbitrarily arrested and taken from their homes by armed men in military uniform who arrived in blue military trucks or four-by-four pickup trucks, generally around or after the time of the curfew. In a number of the incidents, the trucks were marked with the letters BAE. After a day or more, the bullet-ridden bodies of the victims were found along roads in or leading out of Daloa. Sometimes the victims were first taken to the military camps before being summarily executed. Several witnesses from Daloa and other places where such killings took place stated that the loyalist military had lists of names of individuals, and that these people were specifically targeted. Human Rights Watch was told by one witness to the Daloa events that a BAE member had told the witness of the existence of "a blacklist with names of people who coordinated the rebels' actions."38

One such case was a prominent Burkinabé businessman named Tahirou Tinta. Tinta was in telephone contact with a relative several times in the days preceding and on the day of his arbitrary arrest on October 19, 2002. The morning of October 19, Tinta told his relative that he had been warned by a friend in the authorities that his name was on a list that had come from Abidjan, and that the names of other Burkinabé businessmen were also on the list. Tinta said he had been advised by this person not to sleep in the same place each night and never to go out alone.39

The relative told Human Rights Watch that Tinta and other Muslim northerners and immigrants became increasingly worried about threats to their security after the loyalist forces re-captured Daloa and articles appeared in the government newspaper accusing Dioula of supporting the rebels (see above). Their concern deepened on October 17 when the home, vehicles and stores of some Muslim businessmen in Daloa were ransacked and looted by groups of mainly Bété youths acting together with the gendarmes.40 Human Rights Watch was told, "the BAE came with a tank and smashed the door of the Malien consul. They beat one of his visitors, then the young Bétés and the municipal police came and looted and burned his cars, then they went to the stores and started taking merchandise."41

The evening of October 19, at least eight armed men in uniform, described to Human Rights Watch as gendarmes, came to Tinta's house in two four-by-four pickup trucks. Some stayed outside the house while others came in and demanded money. They took Tinta from the house that evening, along with a substantial sum of money. His body was found the next day, with gunshot wounds, on the side of a road in Daloa.42

According to a witness who helped collect and bury the bodies, between October 15 – 20 at least two bodies were found each day.43 On October 20, the BAE's mopping-up activity culminated with an operation in the largely Dioula Orly II quarter, which they encircled with four-by-fours and tanks. Approximately fifty armed men then entered the quarter and checked identity cards. Based on reports gathered by Human Rights Watch, a large number of people, mostly young men bearing northern or immigrant names, were then shot on the spot and their homes were looted. According to the local Red Cross, twenty-two bodies were found following this operation, which were buried in a mass grave.44 Hundreds of panicked northerners fled the quarter, and many sought refuge in the Grand Mosque of Daloa.

The following day, young northerners and Muslims in Daloa demonstrated to protest the events. Muslim leaders and neighboring governments whose nationals had been killed also lodged protests with the government in Abidjan.

In reaction to press reports and growing accusations against the armed forces on the Daloa killings, the spokesperson of the armed forces admitted that cleaning up operations were still taking place, despite the government re-capture of the town and a cease-fire signed between the government and rebels on October 17. However, armed forces spokesperson Jules Yao Yao denied that civilians had been intentionally targeted by the armed forces. He said, "Every day bodies of people who died in combat are discovered amid the searches. These are not people intentionally killed by the armed forces, but individuals killed in combat. Elsewhere, based on the definition of assailant given by the head of state, the cleaning operations involve individuals who lodged or actively helped the assailants."45 In a clear and damning statement of policy, the government spokesman continued, "The enemy, for the regular forces....is foremost armed men and then the civilian population who actively support them."46

The government continued to deny that state security forces were responsible for the killings, but announced an investigation on October 25.47 Notably, the killings in Daloa stopped after the attacks were publicized, condemned locally and internationally, and the BAE forces left Daloa. However, the pattern of reprisal attacks against civilians exhibited by the BAE and other state security forces in Daloa was replicated in other locations.

The massacre at Monoko-Zohi: November 28, 2002

On November 27, the day before the rebel groups launched their offensives on Danané and Man, the government forces sent troops northwest from Daloa, across the cease-fire line into rebel-controlled territory, probably in an attempt to attack Vavoua. On November 28 and 29 the government forces attacked Monoko-Zohi, a tiny village about seventy kilometers from Daloa. Monoko-Zohi and other villages in the district, such as Pélézi, Fiekon Borombo and Dania, had a mixed ethnic population of indigenous Ivorians, mainly of Niédéboua ethnicity, and foreign immigrants, largely Burkinabé, who were the main cultivators of the area's cocoa and coffee plantations. There were pre-existing tensions between these two groups of villagers due to conflicts over land (see below, chapter IX). A Burkinabé farmer interviewed by Human Rights Watch described the collaboration between some of the indigenous Niédéboua villagers and the loyalist forces in the neighboring Pélézi village:

Pélézi is mixed, there were lots of foreigners – Burkinabé, Maliens, Guineans, Nigerians, and then the Ivorians--the Niédébouas and Baoulés – living there before the war. After September 19, there was a lot of tension with the Niédéboua villagers. The Niédéboua quarter was on one side of the village and the foreigner's quarter on the other side. The Niédéboua said, "[w]e are going to chase you out and take our land.' My Niédéboua friend told me that the Niédéboua had secret meetings after the rebels came in October. They weren't happy that the rebels had come, they said "[t]he president of Burkina Faso was responsible for sending the rebels to CI." They said that if the loyalist forces came, they would chase all the foreigners away. They made a list with the names of the foreigners, I was told this by some of the younger Niédéboua. It wasn't just the Burkinabé, even the Baoulé were seen as foreigners in Pélézi.48

A week after the government attack, French forces visited Monoko-Zohi after receiving alarming reports from civilians displaced from the area. The French troops confirmed the existence of a mass grave reportedly containing approximately 120 bodies of mainly immigrant workers who had been living in the area.49

According to a BBC report based on a visit to Monoko Zohi and interviews with eyewitnesses on December 9, "[s]ix trucks full of men wearing Ivorian military uniforms, and with Ivorian Government license plates drove into the village, just inside rebel-held territory, and began firing in the air. Many of the villagers fled. Many of those who did not are now buried in the grave. Accusing the villagers of feeding rebels, soldiers went house-to-house in the hamlet with a list of names, survivors alleged." 50 An eyewitness interviewed by the BBC stated that "soldiers shot some victims where they found them, and gathered others for execution together.... Some had their throats slit."51

The government subsequently denied that its forces were responsible for the killings, noting that the Dania area was under the control of the rebel forces at the time of the massacre. The MPCI refuted this, claiming that government was not acknowledging its attacks in the area, and claiming that the Monoko-Zohi mass grave was only discovered after an MPCI patrol visited the village on December 4.52

While the events in Monoko-Zohi require further investigation, particularly with forensic expertise, many factors point to government responsibility for the massacre. The modus operandi of the killings, which corresponds with that used by government forces in other locations, the accounts given to international journalists by eyewitnesses at the site shortly after the events, and Human Rights Watch's own interviews with individuals who were in villages in the area, confirm the presence of government forces in the area and their collaboration with local villagers hostile to the immigrant population. These factors consistently point to the government's armed forces as the perpetrators of the killings.

Government forces recapture Man: December 1-18, 2002

A mixture of rebel forces captured Man on November 28. The government counter-attacked and succeeded in recapturing Man on November 30. The loyalist forces then held Man for at least two weeks, until the town was re-taken by the rebels on December 19, 2002.

Prior to the rebel capture of Man on November 28 and during the eighteen-day period in which government forces resumed control of the town, there were credible accounts of killings and "disappearances" of civilians by the government forces. An anonymous medical source in Man stated on December 9 that "about 150 bodies had been cleared from the streets of Man since it was retaken by government soldiers.... The victims included several people who had been executed."53 However, this figure likely included the bodies of both rebel and government combatants killed in fighting as well as the bodies of civilians unintentionally killed in crossfire.

Further investigation, including forensic analysis of several mass grave sites in Man, will be required to establish the identities and methods used to kill the individuals whose bodies are in the sites. Nonetheless, Human Rights Watch has documented several incidents in Man where civilians were summarily executed by government forces during the period of loyalist control of the town and fears these may be only a fraction of the real number. A twenty-year-old Ivorian youth described the loyalist re-capture of Man and the summary execution of his neighbor, a transporter named Yacouba Sylla, to Human Rights Watch.

There were mercenaries working with Gbagbo – Angolans and South Africans – who were the advance troops, they arrived before the loyalists came into Man. People were able to move around the town, the curfew was 19:00 and the mercenaries were okay. The Angolans had yellow uniforms very different from the Ivorian army uniforms. They didn't speak French, when you said something, they didn't understand. The South Africans were mostly white...they gave people bread and wore khaki and tricots.

Then the loyalist troops came, things changed. They imposed a curfew of 16:00 and forbid people to move around. I stayed in after that....When you get up in the morning, you go outside and you would see bodies on the road. I heard of many killings in the other quartiers, but those I know are the ones from my quartier, like my neighbor, Yacouba Sylla. He was a Dioula, an Ivorian originally from Odienné. He was working in transport – he had five trucks. At this time, when the loyalists came to Man, he was the only person in his house, because the rest of his family had escaped. Sylla stayed because of his transport business.

There were four gendarmes who came to Sylla's courtyard. They came in a four-by-four, in uniform, and they carried machine guns. They knocked on the door, and when Sylla arrived, they began to beat him. They said, You the Dioula, you support the rebels.' Sylla protested that he was innocent, but they beat him. They shot him twice, then searched the house for guns but they didn't find anything. The family had already fled. In the morning, when I left my house, his body was lying in the street. With some other people from the quartier, we brought the body to the hospital morgue and called one of Sylla's sons, in Biankouma. He was too afraid to come to Man to take care of the body, he asked us to ask the local Muslim community to help. I left Man soon after that, so I don't know what happened to the body. 54

The majority of civilians targeted by government forces in Man were thought to be Yacouba and Dioula youths suspected of sympathies towards the rebels. In practice, this often translated into targeting members of the RDR or the UDPCI, the western-based party that supported General Guei. Individuals working in the transport industry were also suspect, as shown above, according to the logic used by the armed forces. Suspicions could fall on an individual simply because he carried an amulet or a certain kind of ring and was therefore thought to be a combatant who needed magical protection or a "dozo," one of the traditional hunters recruited by the MPCI. As in other places controlled by government forces, a number of the victims were identified from lists of names compiled by local authorities and civilians.

Another witness interviewed by Human Rights Watch described this period of government control:

There were many killings under the loyalists. If the loyalists found you with an amulet ring, then they would kill you because they suspected it was a protection from fighting. They made a mass grave – there were so many deaths.... Matthias, the president of the UDPCI-youth, he was taken by the loyalists and we never saw him again. There were many killings, and the family had no rights to ask about what happened. When we talk about the loyalists, it's the gendarmes and police, but also the Angolans and South Africans. It was the gendarmes from Abidjan who did the killings though. The local gendarmes were mostly killed in the fighting when the rebels took the town....There were many bodies in the streets, some decomposing. The loyalists also left many bodies in the cemetery. [They] would take bodies in military trucks to the cemetery to bury them, or just leave them there. 55

As these killings were taking place, the Ivorian army spokesperson stated, "the cleaning operation and the consolidation of republican forces is on-going in the town and vicinity of Man. Life has returned to normal in that area."56 Ten days later, the rebels re-captured Man.

Summary executions by government forces in other locations in the west

Human Rights Watch also documented summary executions of civilians, particularly members of the RDR, by government armed forces in other western towns under government control, including Bangolo, Duékoué and Guiglo.

In Bangolo in mid-December, the summary execution of a teacher – and RDR member – was witnessed by at least three people.

Two gendarmes came to the house around 14:00. [They] were armed with machine guns and dressed in military uniform. [They] asked his wife if her husband was there. When she said yes, they asked him to come out, then they looked at his identity card and said they were taking him to the gendarmerie. Then one of them said it's not worth it,' and shot him in the right arm, then again in the left arm, then in the stomach. He fell. Then they said, No one can touch the body, if anyone touches the body they'll die. A rebel does not deserve burial.' For two days the body was in the street, no one dared touch it. Finally his wife paid 15,000 CFA to some Guerés to pick up the body on a stretcher and take it away. They threw it off a bridge on the road to Man. 57

Human Rights Watch also heard allegations that in Guiglo, the municipal authorities "made a blacklist of one hundred forty people" with the names of leaders and members of the UPDCI and RDR, and that "the objective was to kill all the people on the list."58

As described below in Chapter IX, a number of Burkinabé were also victims of summary executions by government forces in Duékoué and other locations.

Indiscriminate and targeted helicopter attacks

Human Rights Watch documented two series of helicopter gunship attacks on villages and towns in the Vavoua and Zouan-Hounien regions in early December and mid-April, part of the loyalist offensives on both areas. These attacks were sometimes characterized by the indiscriminate and in some cases direct targeting of civilians. For instance, dozens of civilians were killed when helicopter gunships attacked market places, a medical clinic, and neighborhoods known to have concentrations of foreign nationals accused of supporting the rebels. The MI-24 helicopters used in these attacks were reportedly piloted by mercenaries.59

Indiscriminate helicopter attacks on the Vavoua and Pélézi area: December 2002

The first aerial attack on Vavoua town was the only one of the attacks documented by Human Rights Watch which appeared to target a military objective. In this attack, the fact that the rebels' military barracks were situated in the city hall, in the middle of the town, contributed to civilian casualties. A forty-nine-year-old Burkinabé market woman from Vavoua described this attack to Human Rights Watch:

In late-November, it was a Wednesday, a helicopter came from the loyalists at about 6 p.m. I was in the market when the helicopter came from the direction of Daloa and started dropping bombs on the town. I started running, but I fell down and cut my knees. I went into a store and hid there until things quieted down. The plane dropped bombs on the city hall. The rebels had taken the city hall and sous-prefecture, that was where they had their military camps. The city hall was encircled by a wall, with trucks and weapons in the courtyard. The rebels shot at the helicopter, they managed to get one shot at it before it returned to Daloa.

Three people were killed in the bombing, they were about ten meters from the city hall. One of the people killed was a Nigerian, I didn't know the others. That was the first time the helicopter came to Vavoua, but I heard that it also went to small villages like Pélézi and Monoko Zohi.60

Eyewitness descriptions of other helicopter attacks on other villages indicated that these attacks were clearly indiscriminate in their targeting of civilians. Three attacks on Pélézi, Dania, and Mahapleu resulted in the deaths of at least nineteen civilians, and these attacks represent only a fraction of the total civilian casualties from helicopter attacks. An attack on Mahapleu, which took place in late-December as the rebel and loyalists forces were fighting for control of Man, was a clear example of the type of indiscriminate bombing taking place.

Mahapleu is a small town on the main road fifty-three kilometers east of Man in the direction of Danané. Many people who fled Danané and Man towards the borders with Guinea and Liberia passed Mahapleu on their way out. A twenty-eight-year-old Ivorian driver who had witnessed the helicopter attacks on Danané, was searching for his family in Mahapleu on the day of the attack.

It was a Wednesday, which is market day in Mahapleu. It was about 1 p.m.... We were walking west...when we heard the helicopter coming from the direction of Man. It flew very low towards the market. The market is just along the big road to Man, and many people in the market came out to look.... We ran in the other direction. It was about sixty or eighty meters from the market when it fired. It fired twice in the direction of the market, with rockets that came out sideways. One of them hit the road and broke the road up into pieces. Some people died from that, from being hit by pieces of the road, rather than from the bomb. Then the helicopter flew into Mahapleu town. It went into the town and bombed the mosque and destroyed it.

There were rebels in the village, but they were at the checkpoints outside, along the road, not in the market.... I helped bury the dead from the helicopter attack. We buried five people that day. There were two young Mossi men, two Dioula: a young man and a girl about thirteen-years-old, and one Yacouba woman who ran a maquis in the market. The next day, three more were found dead, under the stalls in the market. They must have been injured and died while trying to get away. I saw the bodies but I didn't help to bury them. Two were young girls. One had been hit in the back of the head and the other in the stomach. They were covered in blood and so swollen it was hard to tell their ages. The third was a boy, maybe twelve or thirteen years old. I left and spent the night at an encampment in the bush...there was another woman there who had been hurt in the helicopter attack, she died in the bush that night.61