GER DUANY: My Transformation in the United States

The ups and downs of my life experience gave me the gift of adaptability. In the US, I found stability and grew as a person in my new homeland.

The opportunity to live in the United States represented a new beginning for me.

Being a refugee was hard. Everything was unfamiliar—the food, mannerisms, infrastructure, geography, culture. I had run away from my environment and everything that I knew to seek refuge in someone else’s.

I had lost my way of life; my values were challenged. I paid with my soul to follow new dreams. I had become an immigrant, cut off from my way of knowing how to do things. Still, I was eager to learn, adapt and integrate.

Naturally, I had my share of struggles—some linked to horrible memories of war and death that continued to haunt me and others related to adapting to a new life in America. Whenever I hear of people who are in trouble with the law, have dropped out of school, or have in any way not been able to take positive advantage of opportunities, I am reminded of the many times when I could have fallen by the wayside.

I was fortunate to eventually find myself in a supportive family setting, embraced as a son and sibling by my Uncle, Aunt and my cousins. Thanks to them I was anchored in a safe and compassionate space, which gave me the grounding I needed to find my feet.

My achievements in sports and in the classroom helped to transform the way I saw and thought of myself, opening my eyes and my mind to realms of possibilities that I could not have imagined amid the violence that characterized my early adolescence.

I’ll never forget the journey from Dadaab’s Ifo refugee camp.

The butterflies in my stomach were in a frenzy on the road trip to Nairobi and later on the flight to Des Moines, Iowa. It was like a fantasy—Ger the village boy airborne for the United States of America! I would not have been surprised to wake up and find myself still in a refugee camp!

The airplane cabin was just like the inside of a bus. The running water in the lavatory were new to me. So was having a full tray of food all to myself. I was used to sharing a tray of beans and maybe a mixture of rice and flour with my comrades while seated on the ground in a circle.

It wasn’t until the plane landed and I set my feet firmly on the soil on Des Moines that it finally sank that Africa was left behind me.

My new journey was very long and there was so much for me to learn including through failure.

My former campmates showed off their cars—they actually owned cars! Later I learned they had chosen credit. They spoke fluent English. It seemed like a remarkable feat! And oh, I’ll never forget my first shower. I couldn’t figure how to balance the flow of cold and hot water. It got warmer and warmer, then scalded my back. I screamed and rushed out of the bathroom. I thought I’d broken the tap. The pain was excruciating, but I kept it a secret until years later.

I had the full summer to get used to things before I started school. I learned to speak English by watching YO MTV RAP and BET on television. It took a Herculean huge effort for me to complete my freshman year.

I tried hard to forget the ordeals of my life before coming to the United States. For the longest time I did not talk about them. I did not think anyone would relate to my experiences on the frontline and in refugee camps.

I tried hard to forget the ordeals I experienced before coming to the United States. For the longest time I did not talk about them. I did not think anyone would relate to my experiences on the frontline and in refugee camps.

The seed of the Hoops dream in America was planted in my mind by a US lawyer I had met in Ifo refugee camp, and in America I developed a passion for basketball.

One day at the YMCA in Des Moines, the guys showed me how to dunk. I grabbed the ball, soared into the air and slammed it through the hoop. When I let go of the rim, I fell on my back. I blacked out. That’s how I started to play. Basketball helped me to escape troubling memories.

A year went by. I was not getting along with the man who had been designated to be my guardian. So I left and stayed with friends in South Dakota until I summoned the courage to call my Uncle Wal.

Words cannot express how indebted I am to my Uncle Wal, Aunt Julia and my cousins. They embraced me as a son and sibling, and provided a safe and compassionate family setting that gave me the grounding I needed to find my feet.

With my family’s support I learned to become a boy all over again which enabled me to spread my wings.

I was nervous. What if he turned me away? He did not know me. I only knew of him as a prominent politician in Sudan. I was one of his younger brother, Thabach Duany’s sixty kids.

“Take him back to where you found him!” my irate Uncle yelled at the driver. Clueless about the transport system, I had ridden a cab from Indianapolis. I couldn’t even pronounce Bloomington, the name of the place where my Uncle had lived his family since 1984. All I had was an address written on a piece of paper by a friend who looked up to my Uncle as a scholar, and the determination to see my relatives.

The fare was something like $100. I had no idea about the value of the US dollar. Where I came from, we placed value on our cattle. Perhaps the cab driver had hoped to take advantage of my naivité or he thought simply that I was fair game. Suffice it to say, he agreed to a reduced fare.

I was welcomed warmly. I got the room my cousin Duany Duany was vacating as he headed to University in Wisconsin on a basketball scholarship. I became one of the family with my Uncle Wal, Aunt Julia and cousins Kueth, Nok, Nyagon and Bill.

With my family’s support I learned to become a boy all over again which enabled me to spread my wings.

My cousins had lived in Bloomington pretty much all of their lives. All they knew was basketball; all I knew was warfare. I didn’t think they would relate to my experiences in conflict and in refugee camps. I tried hard to forget that chapter of my life.

Sometimes I felt lost and alienated but I didn’t tell anyone about the ordeals I had been through. I couldn’t even bring myself to tell Aunt Julia why I felt exasperated when she encouraged me to join the United States Army.

So much from my past was bottled up inside. Pent up fears and often anger would surge through my being like volcanic lava, needing to explode. I realized that such emotions could only be destructive. I knew instinctively I could not survive if I allowed my rage to get the better of me. So I learned to listen, and to pay attention to very small things. I thank the universe for that intuition. Time took care of me; it carried me a long way, and life continues to happen.

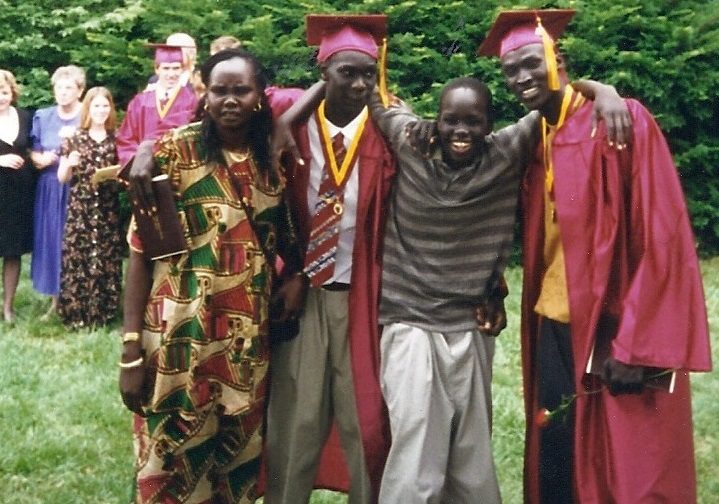

When I graduated from high school, I was overjoyed. Something stirred inside of me. I started to recognize a strength I had not known. There was much more to me than I had ever seen in myself. I was awakening to a new perception that there was much more to me than the ordeals of my childhood. I thought, “I’m not a war victim anymore”. It lit up my world.

I thought how proud my mother and father would be. Memories swam in my head of running, stealing and getting shot at in the long grass of Anuak villages. I wondered, ‘What if I had not gone through it? Would I ever have graduated from high school in Indiana?’

In my new state of self-awareness I became hopeful for the future.

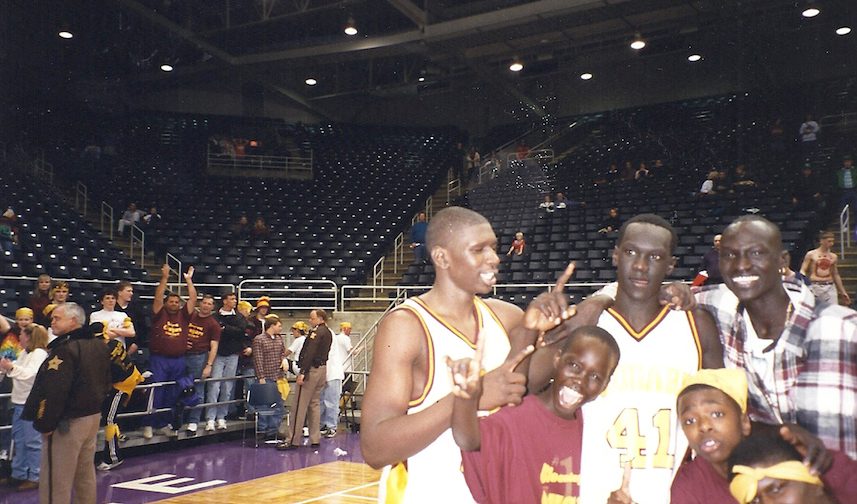

I graduated with a basketball scholarship to Lake Land College and L.A Southwest College. The Hoops dream in America unfolded before me as I signed the intent letter.

I did well at Lake Land College, even helping the team win a state championship in L.A. Southwest College. After finishing my associate’s degree, I earned another basketball scholarship to the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut. It was a new chapter of my life.

I capitalized on the opportunity and worked hard to obtain a Bachelor Degree in Department Human Resources, Specialized in Human Services.

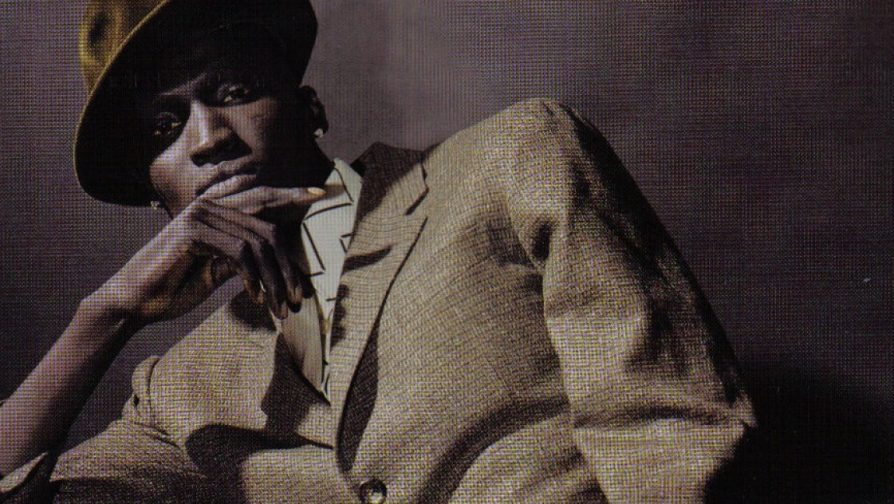

This picture from my first photo shoot was taken by New York fashion photographer Norman Watson and published in the September 2005 issue of Fader Magazine.

The ups and downs of my life experience had given me the gift of adaptability. I had found stability and grown as a person in my new homeland.

My entry into the film and fashion industry was fortuitous.

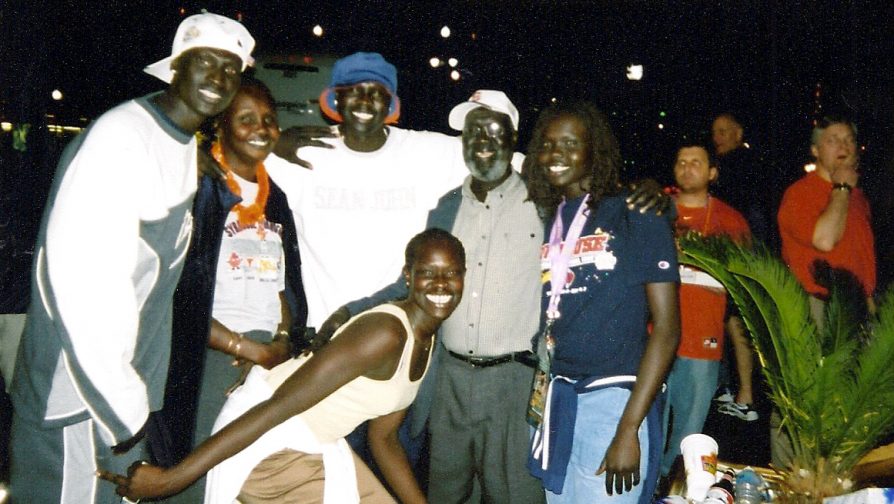

In 2003, Mary Williams, head of the Lost Boys Foundation (and Jane Fonda’s adopted daughter) was asked to mobilize young Sudanese men to audition for the role of a refugee in a feature film. My cousin Kueth of Syracuse and I traveled with my friend Manute Bol, Luol Deng of Blair Academy, and his brother Ajou Deng of Fairfield University.

We drove to Hartford to join dozens of other Hollywood hopefuls in a day of auditions. It felt like a South Sudanese reunion. We had learned that David O. Russell wanted to cast a kid who had experience as a refugee, so we all showed up. It was a fun day.

I didn’t put much thought into the outcome until I got a call from Shannon Murphy and Mary Williams two months later announcing that I had been chosen, out of hundreds of “Lost Boys”, to appear in I Heart Huckabees. Shannon Murphy had always encouraged me get work in the entertainment industry. I was pleasantly surprised, though totally oblivious to the new possibilities that would open up for me.

Universal Studios flew me to Los Angeles in business class, heralding a new experience in a world of opulence that entirely alien to me. The next morning I sat in a trailer with Jason Schatzman, Jonah Hills, Dustin Hoffman, Mark Wahlberg, and Lily Tomlin. The friendliness of Hollywood both astonished and warmed me. Everyone was so nice to me.

Dustin Hoffman said, ‘Hey, come to my house and have dinner.’ Mark had a huge house and several cars, which was totally amazing to me. I had personal stylists who were fitting me in new suits say, ‘You’re such a handsome man.” Jude Law welcomed me backstage. Movie director, David O. Russell, gave me a hug after calling out, “Cut!”.

And I thought, ‘Okay. This is opposite of the basketball environment where coaches usually hollered, “BOYS, this ain’t no democracy!” I had to get used to Hollywood as a “huggy” place. All those kisses flying back and forth.

The film opened up a world of opportunities for me. I met Wahlberg’s friend Ralph Lauren and fashion model Tyson Beckford. Tyson encouraged me to try modeling. I felt at home in front of the camera from my first shoot, which was with New York fashion photographer Norman Watson.

The skills I had learned in basketball helped me, because you have to take detailed directions from your coach just like you do in a shoot. I took it very seriously. It became comfortable and natural. I could just be myself.

Though immersed in the glamour of Hollywood and the fashion world, I thought ceaselessly about home and about life in Great Akobo.