Missing Out: Refugee Education in Crisis

Education enables refugees to positively shape the future of both their countries of asylum and their home countries when they one day return.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency released a report today showing that more than half – 3.7 million – of the six million school-age children under its mandate have no school to go to.

Some 1.75 million refugee children are not in primary school and 1.95 million refugee adolescents are not in secondary school. Refugees are five times more likely to be out of school than the global average.

“This represents a crisis for millions of refugee children,” said Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees. “Refugee education is sorely neglected, when it is one of the few opportunities we have to transform and build the next generation so they can change the fortunes of the tens of millions of forcibly displaced people globally.”

The report compares UNHCR data on refugee education with UNESCO data on global school enrolment. Only 50 per cent of refugee children have access to primary education, compared with a global average of more than 90 per cent. And as these children become older, the gap becomes a chasm: only 22 per cent of refugee adolescents attend secondary school compared to a global average of 84 per cent. At the higher education level, just one per cent of refugees attend university, compared to a global average of 34 per cent.

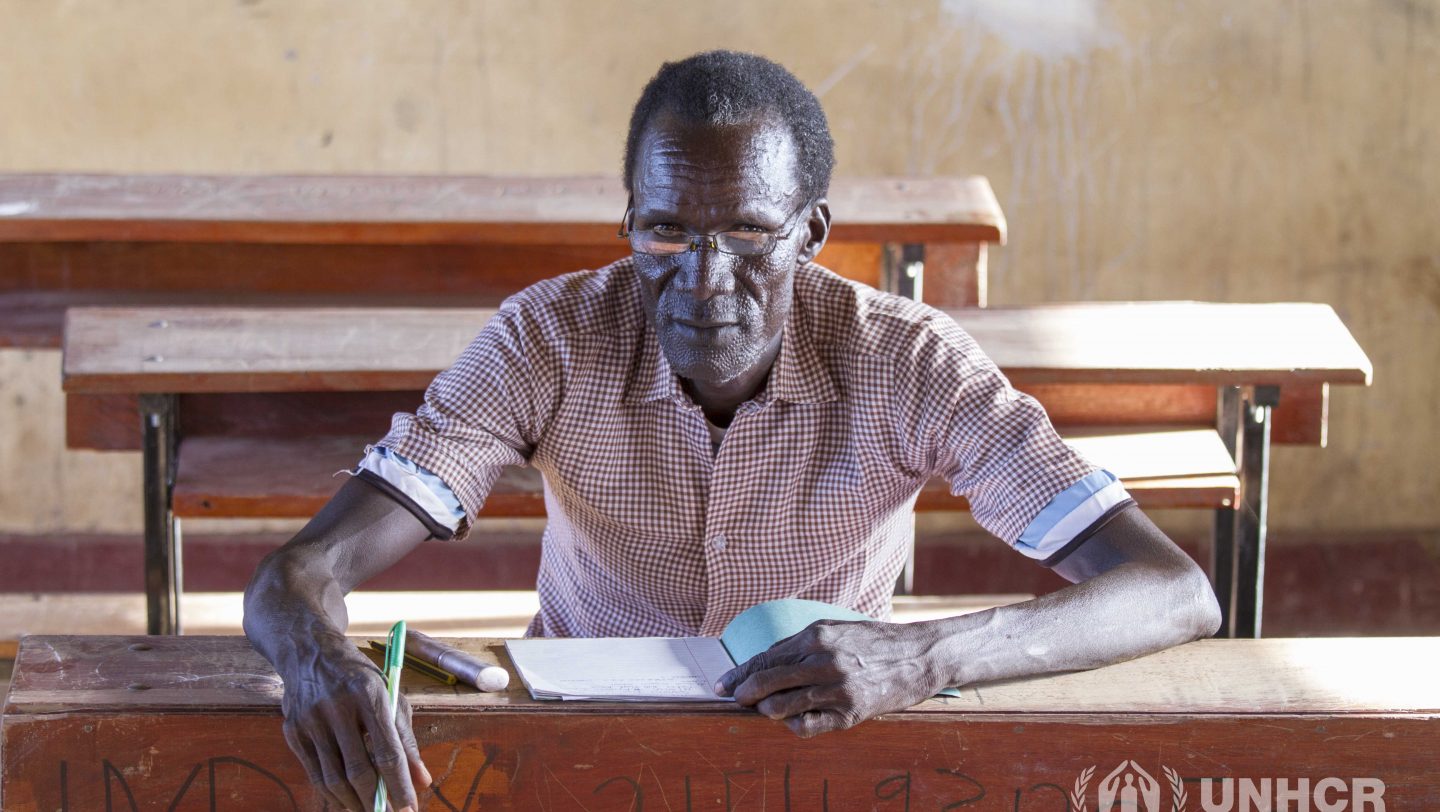

When 18-year-old South Sudan refugee Esther Nyakong, her mother and two sisters reached the northwest Kenya refugee camp at Kakuma in 2008 they had nothing. Esther studied hard, became head girl at the nearby Morneau Shepell boarding school for girls and in 2016 was hoping to beat 100-1 odds and go to university. Eventually she set her sights on becoming a neurosurgeon. UNHCR/A.Karumba

The report is released in advance of world leaders gathering on September 19-20 at the UN General Assembly’s Summit for Refugees and Migrants and the Leaders’ Summit on the Global Refugee Crisis hosted by the President of the United States of America. At both summits UNHCR is calling on governments, donors, humanitarian agencies and development partners as well as private sector partners to strengthen their commitment to ensuring that every child receives a quality education. Underlining the discussions will be the target of Sustainable Development Goal 4, “Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning” an aim that will not be realized by 2030 without meeting the education needs of vulnerable populations, including refugees and other forcibly displaced people.

“As the international community considers how best to deal with the refugee crisis, it is essential that we think beyond basic survival,” said Grandi. “Education enables refugees to positively shape the future of both their countries of asylum and their home countries when they one day return.”

“Education enables refugees to positively shape the future of both their countries of asylum and their home countries when they one day return.”

While the report highlights progress made by governments, UNHCR and partners in enrolling increased numbers of refugees in school, the struggle is one of sheer numbers. While the global school-age refugee population was relatively stable at 3.5 million over the first ten years of the 21st century, it has grown on average by 600,000 children and adolescents annually since 2011. In 2014 alone, the refugee school-age population grew by 30 per cent. At this pace of growth, UNHCR estimates that an average of at least 12,000 additional classrooms and 20,000 additional teachers are needed on an annual basis.

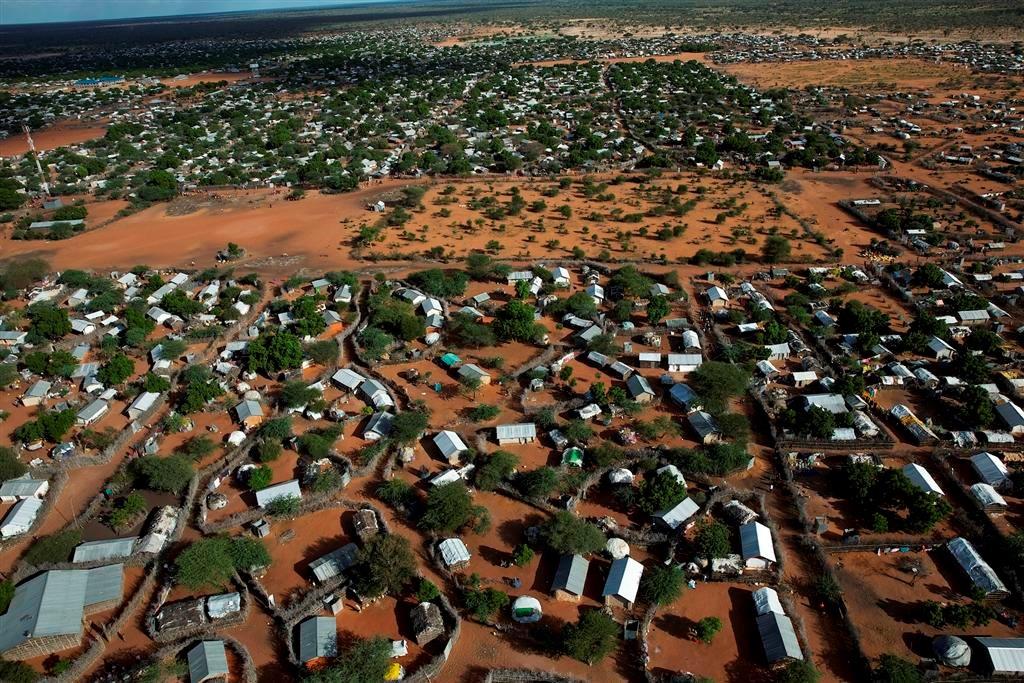

Refugees often live in regions where governments are already struggling to educate their own children. They face the additional task of finding school places, trained teachers and learning materials for tens or even hundreds of thousands of newcomers, who often do not speak the language of instruction and have frequently missed out on three to four years of schooling. More than half of the world’s out-of-school refugee children and adolescents are located in just seven countries: Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lebanon, Pakistan and Turkey.

Exemplified by Syria, the report shows how conflict has the potential to reverse positive education trends. Whereas in 2009, 94 per cent of Syrian children attended primary and lower secondary education, by June 2016 only 60 per cent of children were in school in Syria, leaving 2.1 million children and adolescents without access to education in Syria. In neighbouring countries, over 4.8 million Syrian refugees are registered with UNHCR, amongst them around 35 per cent are of school-age. In Turkey, only 39 per cent of school-age refugee children and adolescents were enrolled in primary and secondary education, 40 per cent in Lebanon, and 70 per cent in Jordan. This means that nearly 900,000 Syrian school-age refugee children and adolescents are not in school.

“As the international community considers how best to deal with the refugee crisis, it is essential that we think beyond basic survival”

In February at the Supporting Syria and the Region conference in London donors committed to a plan to reach 1.7 million Syrian refugee and affected host-community children and youth in Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Iraq and Turkey, and 2.1 million out-of-school children inside Syria. By the start of the new school year in September, the work by host governments is impressive, with Jordan and Lebanon reinforcing their double shift system at schools, 90 per cent of Syrian refugee children enrolled in school in Egypt, and Turkey redoubling efforts to encourage enrolment. However, funding from this conference is still not fully committed, threatening to undermine some of this progress.

“The progress seen in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey points to the potential to turn around the educational prospects of refugees, but only if the international community invests,” said Grandi. “The Islamic Republic of Iran and Chad are good examples of governments pursuing policies to actively encourage enrolment of refugee children in local schools.”

The report also looks at some of the more protracted refugee situations that receive less attention. In Kakuma refugee camp in northern Kenya, the report profiles the remarkable story of a young South Sudanese girl, Esther, who has caught up on multiple years of missed education to reach the last year of secondary school. Only three per cent of children in Kakuma camp are enrolled in secondary school, and less than one per cent make it to higher education.

The report calls for governments to prioritize effective inclusion of refugee children in national systems and multi-year education sector plans. In Chad, a recent transition of all schools to the national system has supported both refugee and host community children. However, lack of funding is resulting in overcrowded and under resourced classrooms.

Given the fact that the average length of displacement for a refugee in a protracted situation currently stands at 20 years, the report calls for donors to transition from a system of emergency to multi-year and predictable funding that allows for sustainable planning, quality programming and sound monitoring of education for refugees and national children and adolescents.

The report concludes with the inspiring story of Nawa, a Somali refugee who only started her education aged 16 at a community learning centre in Malaysia. Under four years later, she is studying a foundation course to enter university while giving back to her school as a volunteer teacher.

“Nawa’s story proves it is never too late to invest in refugee education, and investment in one refugee’s education means the entire community benefits,” said Grandi.

Read the full report here.