By: Keleti Passage Project | 23 November 2015

"We have some stories we'd like you to see," says Gábor Kasza, an artist and activist based in Budapest, Hungary. "Photos of people with messages they've drawn or written for you."

-

Ashkan and Setays, siblings from Afghanistan.

They drew their home, surrounded with a wall and a small crack where they escaped. © Keleti Passage Project

-

Dr. Judit Mogyorós, 42, from Hungary.

Judit works as a paediatrician in Budapest's XIII district. During the three months she worked at Keleti station, she directed 30-40 other health professionals who showed up to help her after work. She told us that without family support, the single men were in a much worse condition, mentally and physically. "They open up easily, desperate for a little human tenderness." Their nickname for her was 'Mami'. We captured one of these moments, when a young Afghan man ran into the shot to give her a goodbye hug. She saw an average of 200-300 patients a day, and on some days over 450. Most cases were skin afflictions (blisters, foot sores) but also kidney stone problems induced by so much walking without replacing fluids. © Keleti Passage Project

-

Fatima, 10, from Afghanistan.

Like many of the refugees we met, Fatima was much younger than we expected and, like many of the children, she drew a future home. She participated in the afternoon and by the evening she and her family had moved on. © Keleti Passage Project

-

Hajrah Arshad, 18, from Norway.

Hajrah was born in Norway and travelled to Budapest to volunteer. She also volunteered at the Serbia-Hungary border, where she was horrified by the conditions. © Keleti Passage Project

-

Hasan, 49, from Syria.

Hasan came from Damascus. He began to cry as he explained he would like to return to Syria before too long. © Keleti Passage Project

-

Maryam Toumi, 18, from Ravenna, Italy.

Maryam's mother is Hungarian and her father is Syrian. The family is Muslim. They live in Italy but she came to Hungary to volunteer. © Keleti Passage Project

-

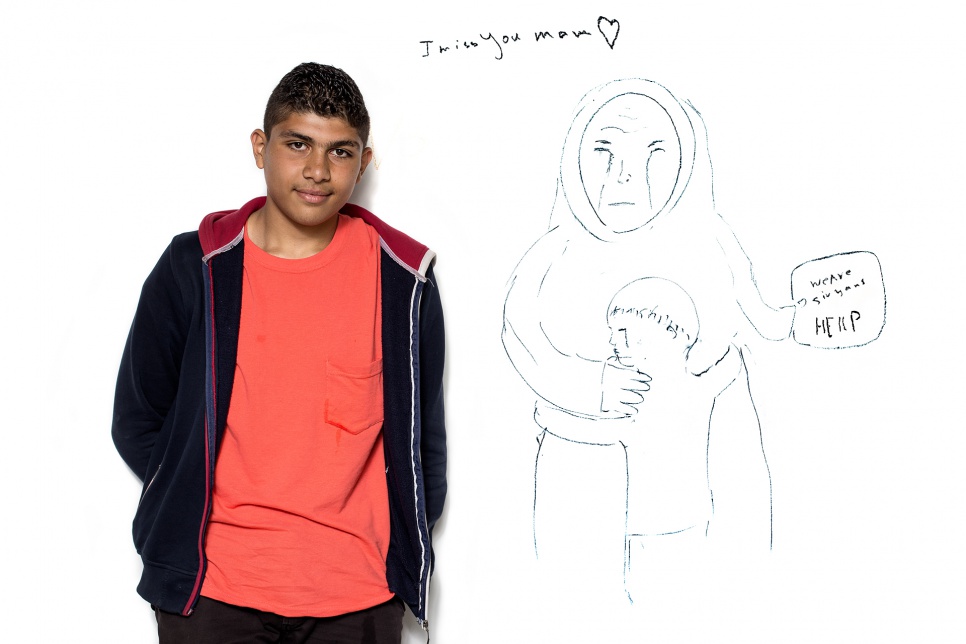

Mohammad, 16, from Syria.

Mohammad's journey to Hungary involved walking for over 100 kilometres. His family remains in Syria. He would like to get them out of Syria as soon as he can. It is common for young people to travel together in groups of four or five. © Keleti Passage Project

-

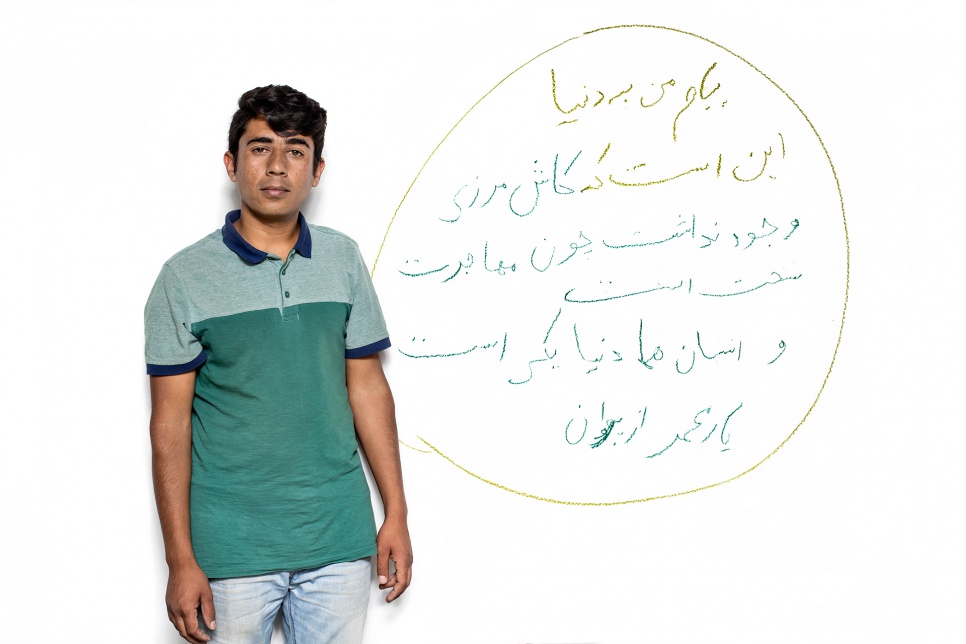

Mohammad, 20, from Afghanistan.

"My message to the world is that even if there were no borders between countries, being a refugee is hard!" © Keleti Passage Project

-

Pariz, 25, and Samir, 23, from Afghanistan with their two-month-old twins, Maholiyar and Maholis.

The children were born on the road -- a situation which is not uncommon. Volunteer doctors even delivered another baby in Keleti Station a few days before they arrived. © Keleti Passage Project

-

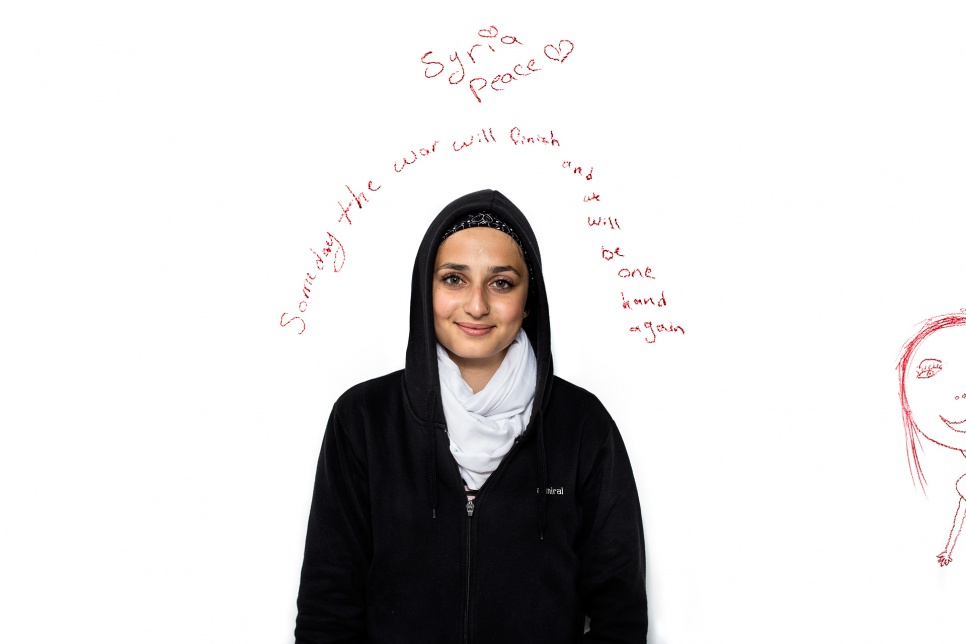

Rawaa, 18, from Syria.

Rawaa left her home in Aleppo, which has suffered some of the worst destruction during the war. Her message: "Someday the war will finish and we will be one land again." © Keleti Passage Project

-

Sarina, four, from Afghanistan.

Sarina drew tiger paw prints on the wall. Along with food and other provisions, art supplies soon appeared at the train station to keep children busy during the long wait. © Keleti Passage Project

-

Váczy Laura, 10, from Budapest, Hungary.

According to estimates, 2,000-3,000 Hungarian citizens, like Laura and her father, personally dropped by Keleti Station to offer snacks, water, clothes, shoes, bedding, tents and personal hygiene items for people in need. Laura drew the two figures beside her and wrote the line "Let's live in peace." © Keleti Passage Project

These images are part of a project which attempts to convey a deeper understanding of the refugees arriving in Hungary in recent months. They are people looking for safety after fleeing war in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. The art also aims to describe the motivations of volunteers coming to their aid, some of whom were immigrants or children of immigrants themselves.

As many thousands of people arrived in the Hungarian capital, Gábor and three fellow artists set up a large roll of paper in Keleti train station. Refugees and volunteers were asked to write and draw their impressions, dreams and experiences. Then, each one was photographed alongside this personal "message to the world."

"The situation is – we have discovered in doing the project – a question and problem of our European identity," Gabor says, explaining that he has noticed a discrepancy between who Europeans are and who Europeans thought they were. "The efforts of our neighbours have inspired hope in us," he says, referring to the way Austrians and Germans have welcomed refugees in large numbers, as well as fellow Hungarians who rose to the occasion and volunteered at sites like Keleti Station.

"These images contain universal and personal messages of human experience," Gabor says, "tidings of wars in distant lands, dreams of peace and hopes for new life in Europe. Their messages are ones which ask us to imagine our own futures as we consider their predicaments. The way we respond to them will define the future of immigration in Europe – and the future of society for all of us."